CHAPTER

TEN

Heartburn and Abdominal Pain

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

• ETIOLOGY

Heartburn and abdominal pain plus associated symptoms are common presentations in ambulatory and urgent care. Gastroenteritis, appendicitis, and peptic ulcer disease are common causes of abdominal pain. Each accounts for 11% to 13% of patients seen with abdominal pain in the emergency room. Similarly, gynecological and urinary tract problems account for 9% and 7%, respectively. The most common cause (20%) is nonspecific. Patients who present with symptoms usually associated with the gastrointestinal tract (heartburn, indigestion, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, bloating, or abdominal distention) may actually have diseases in the genitourinary tract, central nervous system, cardiovascular system, or endocrine system, or they may be due to medications or metabolic abnormalities. Therefore, the assessment of abdominal symptoms must include considerations of problems associated with multiple other organ systems or exogenous issues. Most of these disorders require referral to definitive care, so it is important for pharmacists to recognize common features when patients request help with self-care with nonprescription products.

• DIAGNOSIS

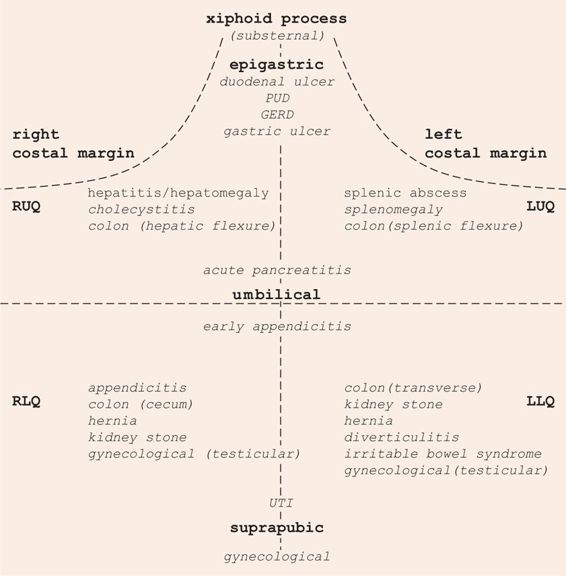

The diagnosis of the exact etiology of abdominal pain and heartburn can be difficult as evidenced by the high percentage of cases in which no specific cause can be found on the first encounter in the emergency room. Part of the problem is the lack of specific innervation of the visceral organs. Pain in one organ may be felt in any of several places. The literature is full of descriptions of “classical presentations” of diseases of the abdomen. However, atypical presentations are common especially in the elderly. For example, the classic pain of gallbladder disease is described as sharp, colicky right upper quadrant pain. Unfortunately, 25% of patients with biliary disease do not present with the “classical” symptoms. Figure 10.1 shows the location of “classical” pain by external anatomical location of the abdominal surface.

FIGURE 10.1 Abdominal architecture.

RUQ = Right upper quadrant, RLQ = Right lower quadrant, LUQ = Left upper quadrant, LLQ = Left lower quadrant.

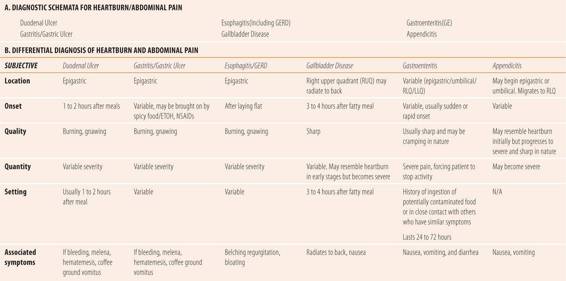

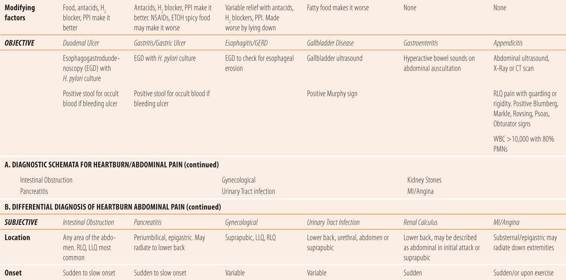

Diagnostic accuracy is dependent on a careful history and physical examination, since there are few laboratory tests that can specifically diagnose diseases that produce abdominal symptoms (Table 10.1). Location of the pain, the type of discomfort, and associated symptoms are usually required to narrow the list of possible diagnoses. Due to expense and exposure to radiation, imaging studies are reserved to diagnose more severe symptoms, or those which evade diagnosis on initial evaluation, especially if something potentially life threatening is suspected. Usually, abdominal x-ray, endoscopy, abdominal ultrasound, or CT scan are used to obtain a specific diagnosis.

| TABLE 10.1 | Heartburn/Abdominal Pain |

• DISEASES THAT PRESENT WITH HEARTBURN OR INDIGESTION

These related disorders usually present with a burning, gnawing discomfort located in the epigastric area of the abdomen. Some describe it as heartburn or indigestion. Medically, it can be called dyspepsia. Peptic ulcer disease is either a duodenal or gastric ulcer. Ulcers occur when an imbalance occurs between acid production and mucosal defense mechanisms. Medications such as NSAIDs, corticosteroids, and Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) facilitate the breakdown of mucosal barriers in both the stomach and the duodenum. Peptic ulcer disease, if untreated, may lead to upper gastrointestinal bleeding and/or perforation. Treatment of these disorders centers on decreasing acid production in the stomach and eradication of H. pylori. Diagnosis of more severe forms of heartburn may require esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) to allow direct observation and biopsy of the lesion.

Duodenal Ulcers

Duodenal ulcers are thought to be due to a combination of excess acid production and a breakdown of the mucosal barrier by H. pylori, a gram-negative bacillus, which is able to live between the mucous layer and the surface epithelial cells of the stomach and duodenum. It attaches to the epithelial cells and by several mechanisms disrupts the mucosal barrier, leading to erosion and ulceration.

Classically, duodenal ulcers present with heartburn that is relieved by meals but returns 1 to 2 hours after eating. Food raises the pH of the stomach, temporarily buffering the acid and causing relief of symptoms. Once the food passes through the duodenum, the pain recurs. Neutralization of stomach acid with antacids or suppression of acid production with H2 blockers or PPIs also relieves the pain. Ulcers will heal with acid directed treatment, but 80% will recur unless H. pylori is simultaneously eradicated.

Gastric Ulcers

Gastric ulcers or ulcers in the stomach also present with typical gnawing, burning epigastric pain, but with no pattern of relief by food. Ethanol can aggravate symptoms and ulcers caused by NSAIDs or corticosteroids are typically located in the stomach. Neutralizing stomach acid or suppressing its production relieves pain in most cases. Here too, treatment requires eradication of H. pylori to prevent recurrence.

Three other disorders have presentations similar to gastric ulcers but may not involve H. pylori in the pathology. First is gastritis, which is an acute event caused by excessive ethanol ingestion or temporary use of irritating medication such as NSAIDs alone or in combination with spicy food and/or ethanol. A short trial of acid suppression and avoidance of inciting issues usually causes the symptoms to disappear until the next inciting event. If symptoms recur without an inciting event, then further diagnostic workup is in order to rule out ulceration or malignancy. Functional dyspepsia is common and has symptoms similar to gastritis and gastric ulcer. The pathology is unclear but appears to be related to delayed gastric emptying time, and intestinal motility issues, but not H. pylori and acid. Not surprisingly, acid suppression has variable efficacy in relieving the symptoms. Finally, in patients over 55, dyspepsia of new onset or heartburn that fails to respond to a short course of acid suppression, gastric carcinoma must be considered. Generally, response of symptoms to acid suppression is variable. The primary reason for the 14-day restriction for the use of H2 blockers and proton pump inhibitors is to prevent partial treatment of symptoms that may be a malignancy, an incompletely healed ulceration, or continued bleeding.

Testing for H. pylori is usually done via biopsy during EGD. The sample can be tested in several ways. The most common and inexpensive is the rapid urease test with >90% sensitivity and specificity. Histological examination is more accurate but is more expensive. Finally, culture of the biopsy specimen is 100% accurate, but is generally reserved for patients who fail initial antibiotic therapy. There are several noninvasive tests for the presence of H. pylori. The first is the urea breath test, which involves ingestion of radiolabeled urea. The urea is hydrolyzed by H. pylori into CO2, which is measured as radiolabeled carbon in the breath. Its accuracy is as good as many of the tests of biopsy materials. Unfortunately, concurrent ulcer therapy interferes with the test, so it is only accurate before any therapy or after therapy is completed because both classes of therapeutic agents cause false-negative readings. Antibodies to H, pylori can be detected in office-based blood and urine tests. Usually they are not as accurate as other tests and cannot distinguish current from past infections. Finally, there is the fecal antigen test, which has accuracy similar to the urea breath test and may be less affected by therapeutic regimens.

Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding

Both duodenal and gastric ulcers can bleed. Sometimes the bleeding is massive, causing the patient to vomit bright red blood (hematemesis). Smaller, but still significant amounts of blood, may make the vomitus appear as coffee grounds, which represents blood partially digested by stomach acid. Significant amounts of blood may not cause vomiting, but do cause the feces to have a black, tarry appearance and consistency (melena). A complete evaluation would consist of vital signs for tachycardia, tachypnea, and orthostatic changes in blood pressure; a BUN and serum creatinine to check for protein digestion from blood; a complete blood count, examination of nail beds conjunctiva or frenulum of the tongue for paleness indicative of anemia; and stool examination for melena or occult blood. See chapter 25 for more details.

GERD/Esophagitis

Gastroesophageal reflux disease or GERD represents a group of disorders that are caused by acid and bile reflux into the esophagus in patients whose lower esophageal sphincter (also called LES or cardiac sphincter of the stomach) does not function properly. In esophagitis, LES tone is either permanently or temporarily incompetent and fails to prevent acid and bile from refluxing from the stomach into the thinly lined esophagus. Decreased LES can be associated with ethanol ingestion, which relaxes the LES, anatomical variances, or a hiatal hernia. Acute esophagitis is caused by a temporary loss of LES tone. Typically, patients with acute esophagitis describe some combination of a large meal, spicy food, and ethanol followed by laying on their stomach as an inciting event. Chronic esophagitis is due to a permanent change in LES tone. There are two major forms of chronic esophagitis. Today, the term GERD refers to chronic erosive esophagitis, which if untreated can lead to Barrett’s esophagitis, which is a precursor to esophageal carcinoma. Nonerosive chronic reflux disease is usually referred to as NERD. It does not carry the associated risk of esophageal carcinoma. All three forms of esophagitis present with typical heartburn symptoms, a gnawing, burning pain that is made worse when lying down, which splashes acid up past the incompetent LES, into the lower esophagus. Acid neutralization or suppression therapy usually relieves symptoms.

Hiatal Hernia

A hiatal hernia is a weakening, break or rupture in the diaphragm, where the opening that normally only allows the esophagus into the chest cavity, allows part of the stomach to slide up into the chest cavity during moments of increased abdominal pressure. While normally asymptomatic, it may cause symptomatic reflux disease. Suspected causes are obesity, poor posture, frequent bending over, or heavy lifting, as well as hereditary and congenital defects. It is common with up to 60% of patients over 60 having some degree of hiatal hernia. For patients with this condition, as well as GERD minimizing straining, heavy lifting, bending over, correcting slouched seating posture, and raising the head of the bed 4 to 6 inches on blocks all can decrease the frequency of esophageal symptoms. Similarly, no eating within 2 to 3 hours before bedtime, avoidance of alcohol intake, and eating smaller meals more frequently also can decrease the frequency of symptoms.

• OTHER CAUSES OF ABDOMINAL PAIN/DISCOMFORT

Cholecystitis (Gallbladder Disease)

Inflammation of the gallbladder is a common cause of abdominal pain. Classically, acute cholecystitis presents with severe, colicky (cramping) right upper quadrant (RUQ) pain, which may radiate to the right upper back and shoulder, which usually occurs 3 to 4 hours after a fatty meal. Many times it is associated with gallstones. About two-thirds of patients will stop inspiration due to pain when deeply palpating the right costal margin and deep breathing is attempted (positive Murphy’s sign). Ultrasound may show thickened gallbladder walls, gallstones, or fluid around the gallbladder. Many patients will have a history of similar, but much milder symptoms in the past. While sharp colicky pain is common, 25% of patients present without it. Patients may complain of more vague symptoms such as heartburn, bloating, or discomfort, occurring 2 to 4 hours post-fatty meal intake. This is more common in ethnic groups such as Hispanics and Native Americans, where the incidence is significantly higher than the national average. In acute disease, patients may present with fever, and an elevated white blood cell count and elevated liver function tests.

Pancreatitis

The causes of pancreatitis range from gallbladder disease to medications. Acute biliary pancreatitis, the most common cause of pancreatitis, represents 35% to 60% of all causes. Gallstones lodge in the distal common bile duct, blocking off the ampulla of vater preventing drainage of digestive enzymes into the intestinal lumen. Heavy alcohol use is the second most common cause of pancreatitis and is called alcoholic pancreatitis. Other causes include medication, hypertriglyceridemia, trauma, and infections by a variety of microorganisms. In 30% of patients, no cause is immediately identified and is termed idiopathic pancreatitis. In patients initially diagnosed with idiopathic pancreatitis, further comprehensive diagnostic workups have identified a specific cause in almost 80% of cases.

Patients with acute pancreatitis present with sharp, constant, severe abdominal pain in the periumbilical, epigastric, or left upper quadrant areas and may radiate to the back. Nausea and vomiting may occur. Physical examination findings may include abdominal tenderness and guarding on palpation, as well as fever. Patients may prefer bringing their knees to their chest to help relieve the pain, instead of lying flat. Serum amylase and lipase if elevated more than three times the upper limit of normal are indicative of pancreatic damage. High sensitivity C-reactive protein may be significantly elevated when tested 48 to 72 hours after the onset of abdominal pain, indicating pancreatic necrosis. Abdominal ultrasound is the initial imaging study of choice for detecting gallstones. An abdominal CT scan with intravenous contrast is the imaging study of choice if gallstones are not detected on ultrasound.

Appendicitis

Classically, acute appendicitis presents as severe pain located in the right lower quadrant (RLQ). Accompanying peritoneal inflammation may induce the peritoneal reflex, which leads to constipation and urinary retention. In a significant number of cases, appendicitis begins as mild to moderate epigastric discomfort, which then migrates to the umbilical region before settling in the RLQ as more severe discomfort. A history of anorexia or nausea and vomiting are also common associated symptoms.

Examination of the abdomen can be helpful in diagnosing acute appendicitis. Gently palpating or percussing over the RLQ can confirm the location. Slow, light, steady pressure over the painful area followed by sudden release of pressure may increase the pain (Blumberg sign). Deep palpation and release, so-called rebound tenderness, adds nothing but unnecessary pain to the diagnostic process. More appropriate is the Rovsing sign where the left lower quadrant (LLQ) is slowly, but deeply palpated followed by a sudden release. A positive sign occurs when increased pain is elicited during the sudden release in the RLQ over the appendix. Having the patient walk, cough (cough test), and/or stand on their toes, then suddenly and firmly drop on their heels (Markle or heel drop test) may elicit localized RLQ pain by moving the peritoneum over the inflamed appendix. The Psoas and Obturator signs use muscle movement/irritation over the adjacent appendix to elicit increased localized RLQ pain. The Psoas sign is an increase in RLQ pain when the patient is asked to lift his straightened right leg up from the examination table against hand resistance on the thigh. The obturator sign is elicited when the provider, while supporting the right leg when lying on the examination table, bending both the hip and the knee at 90° elicits pain upon passive external or internal rotation. In addition, most patients present with fever and have a white blood cell count consistent with a bacterial infection (>10,000 white blood cells/mm3, with >80% mature plus immature neutrophils). Patients with several of these signs and symptoms will require ultrasound or CT scan if the ultrasound is inconclusive to confirm the diagnosis.

Intestinal Obstruction

Intestinal obstruction can be caused by multiple factors. Some common examples include; tumors or masses in the intestine, formation of scar tissue around the intestine adjacent to previous abdominal surgery sites, fecal impaction due to severe constipation, volvulus (twisting of the intestine), and intussusception (enfolding of the bowel lumen into itself). Pain is usually severe, cramping, or colicky. Locations varies and can be in any area of the abdomen but the lower quadrants are more common sites. Patients usually complain of constipation, but initially may have paradoxical diarrhea. It is more common in older patients. Nausea and vomiting are common and vomiting can bring temporary relief of the abdominal pain. Auscultation of the abdomen may reveal high-pitched tinkling bowel sounds or absence of bowel sounds. Palpation of the abdomen may reveal tenderness, guarding, as well as solid masses and percussion may reveal tympanic sounds. Abdominal ultrasound, x-ray, or CT scan is used to confirm the presence of intestinal obstruction.

Chronic/Recurrent Bowel Disorders (Ulcerative Colitis, Crohn Disease, Irritable Bowel Syndrome, Celiac Disease)

Recurrent episodes of cramping abdominal pain accompanied by diarrhea should lead to referral for definitive diagnosis, which usually requires colonoscopy and biopsy. The pain is usually sharp and cramping similar to intestinal obstruction.

Other Considerations

Abdominal pain, especially located in the lower quadrants in females, may represent gynecological or urinary tract problems so the history should include probing for dysuria, frequency, urgency, flank pain, and vaginal bleeding or discharge. Obviously any positive history will require referral.

Some gynecological causes include pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), ectopic pregnancies, and ruptured ovarian cysts. In PID, pain is usually mild to moderate located in lower quadrants and is associated with fever and vaginal discharge/bleeding. Ectopic pregnancy pain is usually severe, with a sudden onset (at the time of rupture), but can be located anywhere in the abdomen. Similarly patterned, but less severe pain is associated with a ruptured ovarian cyst. A pelvic examination followed by ultrasound or CT scan is required for definitive diagnosis.

While problems with the kidneys can be associated with abdominal pain, they generally present as suprapubic, flank or back pain. The pain associated with renal calculi (kidney stones) is usually described as extremely severe, sharp back pain or suprapubic pain as the stone moves down the ureter. However, the pain may be described as abdominal by patients during an initial episode. Pain in urinary tract infections (UTI) is generally described as occurring in the suprapubic, LLQ, RLQ, low back area or flank area in patients with upper tract UTIs (acute pyelonephritis). Pain and discomfort in UTIs are usually associated with dysuria, urgency and frequency. For acute pyelonephritis, fever, flank pain, and nausea or vomiting can be associated with dysuria and frequency. A midstream clean-catch urinalysis with culture and susceptibility is used to confirm the diagnosis. See Chapter 16 for more details.

Finally, pain due to myocardial infarction or angina can sometimes be perceived as heartburn or abdominal pain. See Chapter 9 for more details.

• KEY REFERENCES

1. Ragsdale L, Sutherland L. Acute abdominal pain in the older adult. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2011;29:429-448.

2. Petroianu A. Diagnosis of acute appendicitis. Int J Surg. 2012;10:115-119.

3. Kumar R, Mills AM. Gastrointestinal bleeding. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2011;29:239-252.

4. McNamara R, Dean AJ. Approach to acute abdominal pain. Emerg Clin North Am. 2011;29:159-173.

5. Muniraj T, Gajendran M, Thiruvengadam S, et al. Acute pancreatitis. Dis Mon. 2012;58:98-144.

6. Cartwright SL, Knudson MP. Evaluation of acute abdominal pain in adults. Am Fam Physician. 2008;77:971-978.

7. Panebianco NL, Jahnes K, Mills AM. Imaging and laboratory testing in acute abdominal pain. Emerg Clin North Am. 2011;29:179-193.

8. Hayden GE, Sprouse KL. Bowel obstruction and hernia. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2011;29:319-345.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree