Chapter 2 Heart Failure

Epidemiology

HF affects nearly 5 million Americans and accounts for at least 20% of hospital admissions among people over 65 years of age. Symptomatic HF has a 1-year mortality of almost 50%, conferring a worse prognosis than most cancers. As many as one-half of the patients with HF have normal or only minimally reduced systolic function, and are diagnosed with diastolic HF.

Pathophysiology

Systolic Heart Failure

When the myocardium is weakened, the body attempts to maintain perfusion to vital organs by improving cardiac output and using systemic vasoconstriction to redistribute blood flow. Reduced renal perfusion leads to activation of the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system, which causes extracellular volume expansion that raises end-diastolic volume and improves stroke volume via the Frank-Starling mechanism (this law states that increases in end-diastolic volume lead to increases in contractility and stroke volume). Catecholamines improve cardiac output by increasing heart rate and contractility. These compensatory neurohormonal mechanisms are initially beneficial but become deleterious over time. The systemic vasoconstriction increases the workload of the heart, which can lead to further myocardial deterioration. The raised diastolic pressures are transmitted to the pulmonary and systemic veins, and can cause pulmonary congestion and peripheral edema. Catecholamine activation may worsen coronary ischemia or induce cardiac arrhythmias. Activation of the renin–angiotensin system causes sodium and water retention and may promote further cardiovascular injury, including left ventricular hypertrophy and remodeling.

Diastolic Heart Failure

Diastolic HF occurs when there is reduced myocardial relaxation (e.g., from ischemia, myocyte hypertrophy, aging), increased passive stiffness of the ventricle (e.g., from infiltrative diseases such as hemochromatosis and amyloidosis), or limited ventricle mobility (e.g., from pericardial tamponade or extrinsic compression by tumor). In patients with left ventricular hypertrophy, ischemia may contribute to diastolic HF even when there are no significant coronary stenoses, because the elevated diastolic pressures may impair blood flow through capillaries and small resistance vessels.

Causes and Precipitants

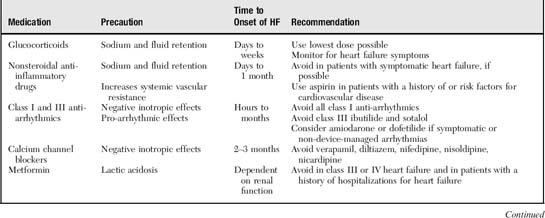

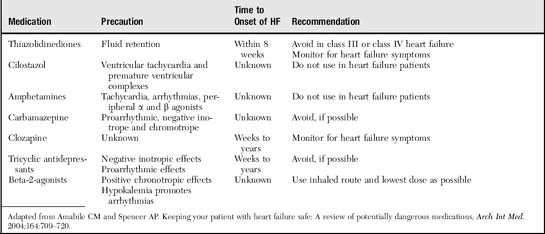

The most common cause of HF is left ventricular systolic dysfunction, which typically results from coronary artery disease (Box 2-1). These patients may have a history of myocardial infarction or may have viable but underperfused myocardium. In patients with a history of HF, a frequent precipitant is dietary or fluid indiscretion or medication noncompliance. Tachyarrhythmias (most commonly atrial fibrillation) may reduce cardiac output by limiting the duration of ventricular filling, increasing myocardial oxygen demands, and eliminating “atrial kick.” Atrial kick refers to atrial contraction, which promotes ventricular filling during diastole. Loss of atrial kick may precipitate HF in patients with stiffened ventricles from diastolic dysfunction. Myocardial infarction or ischemia can cause ventricular stiffening (diastolic dysfunction), reduced muscle mass for pumping blood, valvular leakage from papillary muscle dysfunction, and increased oxygen demand from pain and tachycardia, all of which may precipitate or contribute to HF. Systemic infections or hyperthyroidism increase the metabolic rate, which increases the workload on the heart. Newly prescribed medications may cause salt retention, myocardial depression, or arrhythmias (Table 2-1).

Symptoms

Signs

The goal of the focused physical exam is to determine volume status and to search for potential precipitants of the HF.

1 Jugular Venous Distension

Jugular venous pressure (JVP), which reflects right atrial pressure (central venous pressure), is estimated by examining the internal jugular veins. We do not recommend using the external jugular vein pulsations to estimate central venous pressure, because valves in these veins may lead to inaccurate readings. To assess JVP, turn the patient’s head slightly away from the side being examined and elevate the head of the bed to at least 30 degrees until the jugular venous pulsations are visible in the lower part of the neck. Several features help differentiate internal jugular pulsations from carotid pulsations. The internal jugular vein is not visible (lies deep to the sternocleidomastoid muscles), is rarely palpable, and the level of its pulsations drops with inspiration or as the patient becomes more upright.

The jugular vein pulsations usually have two elevations and two troughs. The first elevation (a wave) corresponds to the slight rise in atrial pressure resulting from atrial contraction. The first descent (x descent) reflects a fall in atrial pressure that starts with atrial relaxation. The second elevation (v wave) corresponds to ventricular systole when blood is entering the right atrium from the vena cavae while the tricuspid valve is closed. Finally, the second descent (y descent) reflects falling right atrial pressure as the tricuspid valve opens and blood drains from the atrium into the ventricle.

Once the highest point of internal jugular pulsation has been identified, the vertical distance between this point and the sternal angle represents the JVP. Regardless of the patient’s position, the sternal angle remains approximately 5 cm above the right atrium. Venous pressure greater than 3 to 4 cm above the sternal notch is considered elevated, suggesting right-sided HF, constrictive pericarditis, tricuspid stenosis, or superior vena cava syndrome.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree