Learning Objectives

- Explore the most current issues of health services management in low- and middle-income countries

- Understand the structure of health systems

- Understand the concept and dimensions of health system performance

- Explore national, organizational, provider, and patient interventions to improve the performance of health systems

Introduction to Health Systems

Have you ever wondered why, in light of great scientific advances, modern communications, and the availability of many cures, treatments, and preventive measures for most diseases commonly found in low- and middle- income countries (LMICs), those diseases still persist and often with great prevalence and incidence? This is the conundrum that we hope to explore in this chapter, especially as it relates to the organization, management, and delivery of services to reach those in need of prevention or treatment of the many diseases, both chronic and infectious, found in LMICs.

To begin, it is important to understand how services that maintain, improve, and restore health are provided to individuals and populations in both urban and rural areas, in light of growing disparities in privilege.1,2

The perspective that is most often used in understanding the delivery of health and medical services is that of a “system,” which is a set of components and their interrelationships, attributes, and properties. From systems theory we understand a system as the continuum of inputs, processes, and outputs. Therefore, within our understanding of the need for health services, the health system is:

- The totality of the required resources, including human, mechanical, material, and financial

- The formal and informal organization interactions and conversions of these resources in the provision of services to individuals and populations to help them maintain good or acceptable health status and improve on it when it is perceived in need, either from disease, physical disability, trauma, or even when perceived as suboptimal3

- The final product of health, which can vary in definition but is commonly understood as the state of complete physical, mental, and social (and even spiritual) well-being or the ability to live one’s life in a manner compatible with achieving one’s social and personal goals, achieving dignity and human rights.

The last theoretical component of systems, for now, is that they are either “closed” or “open.” Closed systems are completely self-contained, are not influenced by external events, and eventually must die because nothing is self-sustainable on its own. Open systems, in contrast, interact with their external environments by exchanging materials, energies, or information, and they are influenced by or can influence this environment; they must adjust to the environment to survive over time. The environment can generally be classified as political, economic, social, and technological, as well as physical (the space available and the way system components relate physically to each other). Thinking of natural disasters and climate and population change, the environment always has an ecological perspective, too.

Health systems are open and must be approached from this perspective. They are open to their local and national environments, and now, ever increasingly, to international and global influences. All the world’s national health ministries are members of the World Health Organization (WHO), are often accountable to more local government, and at times to the people they serve.

Health systems are one of several determinants of health, and high-performing health systems can improve the health of populations.4 Although there is no perfect health system, an understanding of the system in its current form allows us to gain a comprehensive picture of how it and its constituent parts contribute to maintaining health. This, then, helps in understanding the interactions required of its various components. There is an important need for ethical considerations and promotion of equity.

Theoretically, components within a system can be deterministic; that is, the components function according to a completely predictable or definable relationship, as in most mechanical systems; or they can be probabilistic, where the relationships cannot be perfectly predicted, as in most human or human-machine systems, like health care. The WHO suggests that health system boundaries should encompass all actors whose primary intent is to improve and protect health, and to make it fair and responsive to all, especially those who are worst off and most vulnerable to disease and illness.4

What then makes a health system good? What makes it equitable? And how does one evaluate a health system or components of it? The WHO report entitled “Health Systems: Improving Performance”4 provides a detailed presentation and analysis of why health systems matter, how well they are performing, organizational failings, resources needed, financing, and governance. In summary, it defines four key functions of a health system: “providing services; generating the human and physical resources that make service delivery possible; raising and pooling the resources used to pay for health care; and, most critically, the function of stewardship.”4

The then director general, Dr. Gro Bruntland, stated, “Whatever standard we apply, it is evident that health systems in some countries perform well, while others perform poorly. This is not due just to differences in income or expenditure: we know that performance can vary markedly, even in countries with very similar levels of health spending. The way health systems are designed, managed, and financed affects people’s lives and livelihoods. The difference between a well-performing health system and one that is failing can be measured in death, disability, impoverishment, humiliation and despair.”4

- The ultimate responsibility for the performance of a country’s health system lies with government.

- Dollar for dollar spent on health, many countries are falling short of their performance potential. The result is a large number of preventable deaths and lives stunted by disability. The impact of this failure is borne disproportionately by the poor.

- Health systems are not just concerned with improving people’s health, but with protection from the financial costs of illness.

- Within governments, many health ministries focus on the public sector, often disregarding the (frequently much larger) privately financed provision of care.

Health systems have not always existed; nor have they existed for long in their present form. Early attempts to provide organized national and international access to health services have gone through various stages of evolution throughout the last century and will continue to evolve in this century. Early attempts to found national health systems were common throughout Western Europe, starting with the protection of workers, and are now being followed by most countries around the world, in some attempt to provide health care for all their citizens. The first attempt was in Russia following the Bolshevik revolution in 1917, but it took many more years and a Second World War for most governments to catch on. New Zealand, though, introduced a national health service in 1938; in Britain it was in 1948 with the National Health Service; and in Canada, which is widely known for its national and provincial Medicare health system, it was only in 1971. The United States remains the only Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development country without a national health delivery system (although there have been recent attempts in moving toward one), and Cuba remains a model of what a public system can achieve with limited financial resources.5

Today, most countries’ health systems have evolved along two lines: the employee/employer payment scheme or the tax-based model, whereby all tax payers contribute all or part of the required financial input. Both involve a mix, to widely varying degrees, of public versus private service provision. Comparing health systems is an often useful exercise, especially for learning new ideas.

The WHO came into being in 1946, and its efforts to promote viable and effective health services culminated with the Declaration of Alma Ata in 1978, which advocated the concept and strategy of primary health care6 as a means to achieve health for all. Although much debate has persisted concerning the value and utility of primary health care, it remains a viable and recently renewed approach for providing an acceptable level of health services in countries at all levels of economic and social development.7–9 Debate now centers on how best to deliver services through public or private providers, and the appropriate mix of financing mechanisms: government expenditure, out-of-pocket, or various other types of insurance.

Moving toward universal access and insurance coverage is now considered mandatory,10 and the world is moving toward achieving universal health coverage, aimed at giving everyone in a country the health services they need without financial barrier.11 Most developed countries have already achieved this momentum except the United States, where the movement is still under political debate. Canada presents one of the best examples of universal health coverage in rich countries. The five principles of the Canadian Medicare scheme (comprehensiveness, universality, accessibility, portability and public administration) have sufficiently ensured that every Canadian is entitled to the health care they need across the country without financial burdens. Many LMICs such as Mexico, Thailand, Philippines, Vietnam, and Ghana are moving in this direction. Large developing countries such as China and India have made significant progress in insurance coverage in the last decades.3 Since 2002, the New Cooperative Medical Scheme (NCMS), a form of rural health insurance, together with various other urban health insurance plans, have achieved over 90% health insurance coverage of the total population in China.12 Recent studies have identified that NCMS was associated with increased use at the primary care level and reduction in out-of-pocket spending in township hospitals and village clinics.13 India, today, is implementing various state level universal access policies. This unprecedented revolution of health reform will change how health care is financed and paid, relieve the health need of the poor, and contribute to more equitable human development in general. At the health system level, universal coverage will reshape the organization of health delivery and health financing. New perspectives of health financing, including tax-based and employer-based insurance, as well as public private partnerships, have been explored in different countries.14 Universal coverage, together with a primary care–based health delivery system, will contribute to advancing the Millennium Development Goals related to more equitable health rights and better accessibility to health services.15

Health systems matter in the achievement of health, especially for those at the lower end of the socioeconomic spectrum, but also for the wealthy. Although health systems are complex,16 proper health system stewardship and management offers the potential for coordination of multi- and intersectoral services,17 and accessibility of these services for those who need them according to their needs. Health service providers may be from the public and/or private sectors, and how they interact and are coordinated are all issues of great concern within the health system perspective. A systems perspective on health also helps us get out of our “health” box, in thinking that only medical services and technologies are important; rather, through a systems perspective we come to understand that addressing inequalities in income and housing,18 seatbelt laws, safe roads, antismoking legislation, firearm registries, dietary recommendations, workplace safety, and weather predictions all help to maintain good health and longevity. In 2008, the WHO published the final report of a special commission mandated to investigate the social determinants of health. In their report Closing the Gap in a Generation: Health Equity Through Action on the Social Determinants of Health, they demonstrate very clearly the importance of many social factors, previously not considered central and yet having a direct impact on health status. They conclude that “Social injustice is killing people on a grand scale.”19

The Performance of Health Systems

We have already argued that health systems are important to people’s health and that some systems seem to achieve more than others; but to assess this critically, we must measure it against the objectives and intended outcomes of a health system. Health system assessment is essential and practical.20 The World Health Report 2000 defines three objectives for health systems: improving the health of the populations they serve; responding to people’s expectations; and providing financial protection against the costs of ill health.4 Furthermore, it attempts to assess the average level of attainment of a given objective and its distribution across the population. This follows a growing interest in equity, making it an essential element of performance.21 These objectives and measures are discussed here in a general sense, without specifically referring to those from the WHO report. The first, the health status of a population, would be measured by an average, such as life expectancy, maternal mortality, or infant mortality as well as the range of life expectancy across subgroups within a population. It is always important to disaggregate average measures to get a fuller understanding of the actual situation. Today, for instance, we are now learning how to save 1.2 million stillborn babies per year.22

Health systems that systematically neglect certain subgroups while having a good overall average would have a worse performance than one with the same average but more even distribution across subgroups. These subgroups are generally defined by social characteristics such as wealth, education, occupation, ethnicity, sex, rural or urban residency, or religion.23 These groups are chosen because these characteristics should not affect people’s health (although they often do), and health systems should attempt to mitigate these effects where possible by providing targeted access to appropriate services. The difference in health status between these groups—for example, maternal mortality in rural versus urban areas—would be minimized in a high-performing health system. This reflects the degree of distributive justice within a system, which is also a measure of overall effectiveness.

Responsiveness of a health system is also an objective due to interest in governance and a concern for patient preferences, and not only their epidemiologically defined health needs. This is important because patient preference has an impact on health service utilization, as shown by the widespread use of private health services in LMICs, even among the poor and even when free public services are available.24 Fair financing is an important objective because health care costs are unpredictable and may be catastrophic. For example, in China family bankruptcies due to medical expenditures accounted for a third of rural poverty in 2004.25 Universal coverage may not necessarily reduce financial burden on patients because many barriers of health insurance plans such as co-payment, user fees, thresholds and ceilings may prevent patients using them. The rapid expansion of health insurance coverage in China was associated with a 2.5 times increase of hospitalization rate between 2003 and 2011; the proportion of families bankrupted because of hospitalization increased 20%.26 Health insurance plans should be scrutinized using the effective coverage rate, that is, the actual coverage of health insurance plans after, including all patient-related out-of-pocket costs. Thus health systems have a responsibility to reduce the financial impact of health care costs and make payments more progressive, such that they are related to ability to pay rather than likelihood of becoming ill. As part of health performance, health systems research is gaining emphasis. It is important for informing policy,27 including universal health coverage.28,29

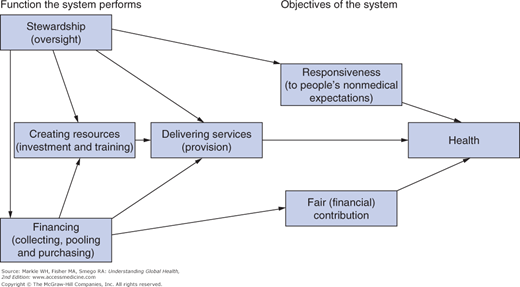

The formal health care system may not be the only or even the main provider of care to a population, but it nevertheless has several functions that promote the objectives of the system (see Figure 20-1). These functions are stewardship, the creation of resources, delivery of services, and financing.4 Stewardship is oversight of the components and functions of the health system, and it is the one function that is undeniably best done by national governments. However, national governments have tended to neglect this function because of a lack of budget, managerial capacity, data, and the unorganized nature of many LMIC health systems, which make this a considerable challenge. The focus of many national health systems has been on service delivery, with most of a health system’s budget being taken up by recurrent costs of curative care, particularly staff salaries and large (capital) city services. Effective oversight would allow governments to assess the performance of the system with respect to the other functions and allow it to target certain areas for reform and monitor the impact of health care reforms.

Creating resources refers to investment in health care infrastructure and training of health professionals. This function is commonly undertaken by the public sector, although some middle-income countries have large private sectors that include medical schools and high-technology facilities with private financing (e.g., in Nepal there are 18 medical schools only 2 of which are public).30 Service provision has traditionally been the main role of health systems, but this is increasingly being questioned because of difficulties with public management in many LMICs. These difficulties have included poor incentives for public providers leading to poor quality and quantity of care (particularly with regard to responsiveness) and widespread use of private sector providers.24 As a result, some authors have suggested that the government’s role should be to purchase services and monitor the quality, as part of the financing function.

Revenue to fund health systems may come from income taxes, like in the United Kingdom and Canada, employment insurance schemes, as in most of Latin America, the purchase of private insurance, or out-of-pocket payments by patients at the point of care, as in India. Because the health expenditure of individuals is unpredictable, prepayment systems with significant coverage protect patients from impoverishment due to health care expenditures. The financial impact of illness also varies according to how risk of illness (and therefore expense) is pooled. Prepayment systems where insurance premiums are based on ability to pay (rather than propensity for illness) allow for cross-subsidy from the rich to the poor and from the healthy to sick. In a sufficiently large risk pool, the costs from year to year will be more predictable and with an appropriate mix of young, old, rich, poor, healthy, and sick, the costs will be affordable for all. Health systems that are financed by income tax provide the greatest potential for pooling risk, whereas those financed primarily by out-of-pocket payments have the worst impact on fair financing. This is because the poor pay a higher proportion of their income than the rich when costs are fixed, and the unpredictable nature of out-of-pocket costs is greater for those with no financial cushion or with limited access to credit.

The Structure of Health Systems

Health systems in industrialized countries are highly structured and were developed in a context of economic stability, with a moderate pace of social change, rule of law, efficient systems for taxation, strong regulatory frameworks, and sufficient numbers of skilled personnel to run these institutions. These conditions are still not found in most LMICs.31 In the second half of the 20th century, many developing countries established national health systems ostensibly designed to provide comprehensive services for the whole population, much like the United Kingdom’s National Health Service, which served as an international model. However, many countries did not fund or staff these services sufficiently to achieve their stated goals, either due to financial crises or a lack of commitment to population health and universality. Most LMIC governments’ incapacity to provide comprehensive health services for the whole population has led to the emergence of other service providers to meet growing patient demand. In these mixed health systems, the distinctions between public and private are sometimes blurred. The more important distinction is between the organized sector, which is subject to some measure of government oversight, and the unorganized or informal sector, which operates according to locally negotiated rules and is largely independent of the state and its regulatory oversight.31

Table 20-1 shows the types of providers and institutions that support the basic functions of a health system, namely public health, consultation and treatment, provision of drugs, physical support for the infirm, and management of intertemporal expenditure (i.e., unpredictable and potentially costly health expenses).32 The providers and institutions are divided into the organized and the unorganized health sectors. The former includes public services run by the government and licensed private providers; the latter includes market-based services, such as those given by unlicensed private providers, and the nonmarket-based services provided by household members, neighbors, and community members. The importance of the various sectors varies tremendously according to the history and relative capacity of each health system. Health policy recommendations should not be transferred from one context to the next without understanding their comparability. For example, in Niger 16% of deliveries are attended by trained birth attendants, so the vast majority of obstetric services are provided by family members in the home (in the nonmarketized sector) or by a traditional midwife charging fees (in the local marketized sector).30 In Sri Lanka, 97% of births are attended by trained personnel, so initiatives to reduce perinatal mortality in these two countries would target very different segments of the health system to achieve similar goals.30

Unorganized health sector | |||

|---|---|---|---|

Health-related function | Nonmarketized | Marketized | Organized health sector |

Public health | Household/community environmental hygiene | Government public health service and regulations Public or private supply of water and other health-related goods | |

Skilled consultation and treatment | Use of health-related knowledge by household members | Some specialized services such as traditional midwifery provided outside market Traditional healers Unlicensed and/or unregulated health workers and facilities Covert private practice by public health staff | Public health services Licensed for-profit health workers and facilities Licensed/regulated Nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), faith-based organizations, etc. |

Medical-related goods | Household/community production of traditional medicines | Sellers of traditional and western drugs | Government pharmacies Licensed private pharmacies |

Physical support of acutely ill, chronically ill, and disabled | Household care of sick and disabled Community support for AIDS patients and people with chronic illnesses and disabilities | Domestic servants Unlicensed nursing homes | Government hospitals Licensed or regulated hospitals and nursing homes |

Management of intertemporal expenditure | Interhousehold/ intercommunity reciprocal arrangements to cope with health shocks | Money lending Funeral societies/informal credit systems Local health insurance schemes | Organized systems of health finance: Government budgets Compulsory insurance Private insurance Bank loans Microcredit |

For each of the key functions of the health system, it is important to understand in which sector the service is being provided for rational planning of the health system. For example, India expanded the number of primary health centers between 1961 and 1988, in an effort to increase access to care.33 Government health planners did not take into account the existing capacity of private health providers (which were widely used); nor did they attempt to provide a service that was considered complementary or competitive by patients, who continued to frequent the private sector. As a result, they invested in public service facilities that remained underfunded, understaffed, underutilized, and uncompetitive with preexisting private and informal providers. For the government to provide adequate stewardship of health reforms, policies should take the existing structure and utilization of the health system into account.

Approaches to Improving the Performance of Health Systems

Now that we have broadly defined the goals, functions, and the general criteria for assessing the performance of health systems, we review a series of approaches to improving performance. Does more health care mean better health?34 We have subdivided these approaches according to the perspective they take or the level of the health system on which they act. There is the national or regional perspective, which refers to policy measures relating to the locus of decision making within the system, the structure of the health system, and the degree of integration of its component parts. The local or organizational level refers to the management of institutions that provide care. Below this is the provider level, the management of health service providers, and the individual perspective, which relates to the engagement or modification of the behavior of health system users.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree