KEY TERMS

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ)

National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA)

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, the medical establishment was shaken by a number of reports that documented wide variations in the way physicians treated their patients for common health problems. One study found that in Morrisville, Vermont, nearly 70 percent of the children had their tonsils removed by the time they were 15 years old, whereas in nearby Middlebury, only 8 percent of children underwent the operation. Another study in Iowa reported that more than 60 percent of the male population of one community had their prostate glands removed by age 85, whereas the rate was only 15 percent in another area. And the rates at which women underwent hysterectomy varied from 20 percent in one part of Maine to 70 percent in a city less than 20 miles away.1

The reasons for these differences were unclear. The populations of the comparison communities were not substantially different from one another. There was no reason to believe that the residents of one community were sicker than those of another or that their insurance coverage was more comprehensive. It seemed obvious that these procedures were being overused in some geographical areas or underused in others. However, the studies could not determine which was true or decide what the appropriate use rates should be.

This method of examining how medical practice varies across geographic areas, known as small-area analysis, has been applied over the past several decades to a broad range of medical practices and procedures. Repeatedly, wide variations have been found, with no apparent reason for the differences in practice. Beginning in 1996, Dr. John Wennberg, a professor at Dartmouth Medical School and a pioneer in the field, who had conducted the studies in Vermont, Maine, and Iowa along with his colleagues, began publishing the Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care series, which examines Medicare data.2 (Since the Medicare program maintains files on everything it pays for, including services to virtually all Americans 65 and older, it provides valuable data for this kind of research.) All over the country, variations occur in treatments for prostate cancer, breast cancer, heart disease, and many other common conditions. For example, for the years 2007 to 2011, the rates of bariatric surgery to treat obesity were 9 per 100,000 Medicare beneficiaries in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, but 75 per 100,000 in Great Falls, Montana, even though Great Falls had significantly lower obesity and diabetes rates. During 2001 to 2011, the rate of spinal fusion surgery for patients with lumbar spinal stenosis (a cause of back pain) was 14 times higher in Bradenton, Florida than in Bangor, Maine.3

Small-area analysis called attention to the lack of scientific evidence on which doctors and patients base decisions about how various medical conditions should be treated. The surprising results of the early studies were part of a new field of research—health services research. This research attempts to understand the reasons for the observed variations in medical practice and to determine, from observations of the everyday practice of medicine, what treatments lead to the most desirable outcomes. Health services research studies the effectiveness, efficiency, and equity of the healthcare system. It is a way of trying to assess the quality of medical care. This research also may lead to insights on how to control costs and improve access.

Reasons for Practice Variations

A number of explanations have been suggested for variations in medical practice, most of which can be tested, and most of which can be shown to play a role in the observed differences. It is clear that the variability in the use of different treatments reflects the degree of uncertainty facing physicians regarding their relative efficacy. Variations in practice are far greater for some medical conditions than for others. For example, most physicians agree that surgery is the appropriate treatment for a broken hip. Correspondingly, the geographic variability in the treatment of this condition is much smaller than the variability in rates for tonsillitis and disorders of the uterus, on which there is much less evidence about when surgery is needed.

In many cases, doctors are unaware that their way of treating a condition is unusual, and they will change their patterns of practice when presented with evidence that they are deviating from the norm. In the early 1970s, Wennberg confronted the physicians of Morrisville, Vermont, with data showing that they were doing tonsillectomies far more frequently than other doctors in the state. The Morrisville physicians reconsidered the indications for the procedure, instituted a policy of obtaining second opinions before deciding on surgery, and ended by reducing the tonsillectomy rate to less than 10 percent of what it had been.1 Similarly in 2009, Atul Gawande published an expose on the very high rate of healthcare spending in McAllen, Texas. Medicare patients there were receiving 40 percent more surgeries, almost twice the number of heart studies, and over twice as many pacemakers, cardiac bypass operations, and other treatments compared to similar patients in nearby El Paso, Texas. In the years that followed, after some local introspection and a bit of outside pressure, the medical community in McAllen was able to reduce the amount of government-funded healthcare spending by as much as half a billion dollars by 2015.4

It is easy to suspect that inappropriate use of tests and procedures is responsible for the observed variations in the frequency with which they are done. While this suspicion is supported by the Vermont experience in reducing tonsillectomy rates and for some of the excessive spending in McAllen, Texas, other studies have found that inappropriate use explains only a small part of the wide variability observed for many procedures.

In one small-area study of three procedures commonly done on Medicare patients, panels of expert physicians examined the files of a random sample of patients who had undergone each procedure. The experts compared the indications for the procedure in a high-use area with those in a low-use area. They were asked to determine, for each patient, whether the decision to do the procedure was appropriate, equivocal, or inappropriate. Coronary angiography—used to identify blockages in the blood vessels of the heart—was performed more than twice as frequently in the high-use area as in the low-use area. Yet even in the high-use area the experts considered it inappropriate in only one-sixth of the cases. Carotid endarterectomy (CEA), which had an almost four-fold variation in frequency, was the procedure most often judged inappropriate. A risky procedure intended to remove blockages in the arteries that carry blood to the brain, CEA was deemed inappropriate in about one-third of the cases done in the high-use area. However, the procedure was considered by the experts to be inappropriate almost as frequently in the low-use area.5

This evidence suggests that, for many medical conditions, more than one response may be appropriate. When faced with a patient suffering from a specific illness, one physician may prefer conservative treatment using drugs and “watchful waiting,” while another physician may believe that immediate surgery is indicated. These opinions tend to be shared by the physicians within a community. Wennberg has called these differences the “practice style” factor. For most of the conditions in question, there was not enough scientific evidence to determine which treatment yields a better outcome for the patient. In many cases, the choice of treatment involves weighing benefits against risks, a trade-off that different patients might evaluate differently if they are given the opportunity to choose.

The high variability and frequent inappropriate use of CEA, together with the high risks from the procedure, inspired several large randomized controlled trials, involving over 10,000 patients, to clarify the indications for and efficacy of CEA. The trials demonstrated that, among carefully selected patients and surgeons, the procedure reduced the risk of stroke and death compared with medical therapy alone. In a later analysis to determine whether the evidence provided by the trials changed medical practice, researchers in New York State conducted a cohort study of all Medicare patients who had had a CEA over an 18-month period in 1998 and 1999. The results were a great improvement over the earlier study: Overall 87.1 percent of the procedures had been done for appropriate reasons; 4.3 percent had been done for uncertain reasons; and 8.6 percent had been done for inappropriate reasons.6

As for coronary angiography, another procedure studied earlier, no such randomized trials have been done to determine appropriateness. It is still a high-variability procedure: A recent study comparing rates in different states found a 53 percent higher rate in Florida than in Colorado. The rate depended in part on the density of specialists in the area.7

Box 28-1 Changing Course on Surgery

In 1886, Reginald Heber Fitz, a professor of anatomy at Harvard University, introduced the term “appendicitis” after discovering that a large fraction of serious pelvic infections were caused by an infection of the appendix. Within several years, medical researchers found that an appendectomy, the procedure to remove the appendix, effectively treated the illness. Since then, the appendectomy has been the standard treatment for appendicitis, with over 300,000 performed each year in the United States, making up over 2 percent of operating-room procedures in this country.8 Lost over the years, however, was Fitz’s observation that one-third of appendicitis cases resolved on their own, and a 1959 study that found antibiotic therapy often to be effective for the condition. Revisiting these historical results, a 2015 study found that antibiotic treatment may be an effective alternative to surgery for acute uncomplicated appendicitis. The study randomized 530 patients with uncomplicated cases to receive either antibiotics treatment or an appendectomy. Seventy-three percent of patients receiving the antibiotics treatment got better without additional care. The remaining 27 percent did require follow-up surgery, but there were no complications from waiting for this surgery that were attributable to the initial antibiotics treatment.9

Similar questions have been raised about the necessity of treating abnormal cells in the milk ducts of breasts, a condition called ductal carcinoma in situ. These lesions can show up in mammograms and have long been thought to be a precursor of cancer, sometimes referred to as “stage 0” cancer. Standard treatment since the 1980s has been a lumpectomy or mastectomy. But a 2015 study showed no mortality difference between women found to have these abnormal cells, whether or not they received surgery, and the general population of women, raising the possibility that many or most of the 50,000 to 60,000 annual breast surgeries for ductal carcinoma in situ in the United States are unnecessary.10

Outcomes such as these are a reminder that even widely accepted medical practices may benefit from scrutiny and are subject to revision.

The Field of Dreams Effect

One factor that has consistently been shown to influence practice styles is the availability of services in a community, as shown in the rates of coronary angiography discussed above. For example, the presence of a greater number of surgeons is accompanied by the performance of a larger number of surgeries. This effect was dramatically illustrated in Maine during the early 1980s, when two neurosurgeons moved to a community and devoted themselves to performing laminectomies—disc surgery for low back pain. The number of laminectomies for the whole state nearly doubled as a result of the work of these two surgeons, although only 20 percent of the population of Maine lived in that community and the adjacent referral area.11 This high rate of surgery, like the tonsillectomies in Vermont, was reduced after the surgeons were confronted with data on practice patterns in other communities.

Research has consistently demonstrated an influence of supply on usage when hospital beds are concerned. A study done in the 1980s comparing Boston, Massachusetts, with New Haven, Connecticut, found that Boston had 4.5 hospital beds per thousand people, whereas New Haven had only 2.9 beds per thousand, even though mortality rates and other measures of quality of care were almost the same in the two cities. Approximately the same percentage of beds was filled in the two cities, meaning that the population of Boston was hospitalized at a higher rate than that of New Haven. When Wennberg and his colleagues interviewed physicians in the two cities, they found that New Haven doctors were not purposely trying to ration care and that neither group of doctors knew that they hospitalized patients more or less frequently than average.11

The Dartmouth researchers’ analysis of Medicare data found that the number of hospital beds in a community significantly influences the kind of care received by dying elderly people.12 Medicare patients in New York City, Newark, New Jersey, and Memphis, Tennessee, are much more likely to spend their final days in a hospital, often in an intensive-care unit, than elderly patients in Portland, Oregon, or Salt Lake City, Utah, who are more likely to die at home. Based on 1994 and 1995 data, the rates at which Medicare patients die in the hospital correlate closely with the number of hospital beds per thousand residents in their community. Researchers call this correlation the “Field of Dreams Effect,” after the line in the 1989 movie about a baseball field: “If you build it, they will come.”

While there is little evidence to show that patients are helped or harmed by the more intensive care they receive in Boston, Memphis, and other high-use areas of the country, the differences in use have a major impact on medical care costs. For example, the average hospital bill for each Medicare enrollee’s final six months of life was $16,571 in the New York City borough of Manhattan, as opposed to an average of only $6,793 in Portland, Oregon.12 In the Boston–New Haven comparative study, Boston’s per capita hospital expenditures were about double those of New Haven.13

Wennberg does not specifically argue that conflict of interest or pecuniary motives enter into decisions that determine use rates of medical services. However, many studies suggest that financial considerations may enter into some physicians’ medical decision making. For example, there is evidence that when physicians stand to profit from the performance of diagnostic tests, they are much more likely to order such tests. Until the practice was outlawed by Congress, physicians who owned an interest in clinical laboratories were more likely to refer patients for laboratory tests than similar physicians who referred patients to labs in which they had no financial interest.14 Similarly, physicians who own diagnostic imaging equipment are more likely to use it than comparable physicians who must refer patients elsewhere for such examinations. Physicians in Japan, who are legally permitted to sell prescription drugs directly to patients (unlike in the United States), appear to favor higher-profit drugs.15,16 A recent surge in complex spinal-fusion operations has been linked to the high rates Medicare will pay to surgeons and hospitals, although there is no evidence that the procedure is more effective at curing back pain than laminectomies or even less invasive approaches.17

Outcomes Research

As we have seen, variations in medical care are greatest for medical conditions for which the least is known about the effectiveness and appropriateness of various diagnostic and treatment approaches. The solution to the uncertainties raised by small-area analysis, therefore, is to study outcomes of these various diagnostic and treatment approaches in order to determine what works. Many policymakers believe that such research will allow the development of guidelines for medical practice, leading not only to more effective medical care but also to cost savings through the elimination of unnecessary care.

The epidemiologic study of medical care is called outcomes research. Whereas epidemiology usually examines the disease-causing effects of exposure to agents such as viruses and toxic chemicals, outcomes research examines the health effects of exposure to medical interventions. Controlled clinical trials are one form of outcomes research, but there are practical, financial, and ethical barriers that prevent conducting controlled trials aimed at answering many important questions about medical care. Outcomes research collects and analyzes data generated by the everyday practice of medicine in order to reach conclusions on benefits and risks of various interventions for various types of patients.

One of the early questions John Wennberg’s group looked into was prostatectomy, the surgical removal of men’s prostate glands. It was a high-variation procedure; in some parts of Maine, 60 percent of the men had their prostates removed by age 80; in other parts, less than 20 percent had.18 The procedure is used as a treatment for cancer of the prostate and for benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), a common condition in older men that causes difficulties with urination. Other treatments are available for both conditions, including watchful waiting, since many cases of prostate cancer never progress to become life threatening. For BPH, proponents of the surgical procedure argued that it could reduce symptoms and improve the quality of men’s lives. Skeptics point out that surgery often has unwelcome side effects.

Wennberg and his colleagues conducted a major analysis of Medicare records to determine outcomes of surgery for BPH. They found that published reports significantly overstated the benefits of prostatectomy and understated the complications. Although only about 1 percent of men died in the hospital, 2 to 5 percent of the patients died in the weeks following the surgery. Moreover, within four years of the surgery, almost half of the patients had required further treatment for urinary tract problems. After eight years, about one in five had needed a second prostatectomy.11 Having the surgery did not increase life expectancy, and the effect on quality of life was mixed: It improved urinary tract symptoms, but it had a negative impact on sexual function.18

The results of these studies indicate a need for better informing patients about their choices and about the probable outcomes of each choice.19 Feelings about symptoms, willingness to accept risks of the surgery, and personal assessment of the possible outcomes vary substantially among individuals. Outcomes research should enable these patients to make informed decisions based on their own values. Effective drug therapies have been developed for BPH, and the number of surgeries performed for this condition declined in the 1990s, perhaps due in part to evidence contributed by outcomes research.20

The number of prostatectomies for cancer has increased, however, due in part to the development of a new screening method that became widely used in the 1990s. The test measures prostate-specific antigen (PSA) in the blood, levels of which have been correlated with the presence of cancer. However, low-grade prostate cancer is very common in older men, and many cases never progress to cause a problem. The follow-up testing and treatment of men whose PSA levels are elevated is invasive and may have undesirable side effects. The problem with the use of PSA screening is that there is no evidence that it reduces mortality from prostate cancer.

In a study conducted by the Dartmouth researchers, Medicare data were used to compare two cohorts of men who lived in areas with different practice patterns for screening and treatment. In the Seattle–Puget Sound area, men were tested at a rate 5.4 times the rate in Connecticut. The researchers found that more than twice as many men in the Seattle area, compared with Connecticut men, were subjected to biopsies of the prostate to confirm the presence of cancer. The Seattle area men were over five times more likely to have a prostatectomy than the Connecticut men. However, after 11 years of follow-up, there was no significant difference in the mortality rates from prostate cancer between the two groups of men.21 This finding was confirmed in 2009 with the publication of results from two clinical trials that followed a total of 259,000 men in the United States and Europe for 7 to 10 years. In both trials, men were randomly assigned to groups with and without PSA screening, and there was little difference in mortality between the two groups.22 In 2011, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, an independent panel of experts appointed and funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (see discussion later in this chapter), reviewed the findings from these trials as well as other studies and recommended against routine PSA screening. Similarly, a 2014 review of the evidence concluded that PSA screening results in, at best, only a small reduction in mortality from the disease and is associated with unnecessary harms.23,24 The problem with finding prostate cancers through screening is that there is no good way to determine which ones are likely to progress rapidly and cause harm and which are indolent and can be left alone.

Inspired in part by Wennberg’s work, Congress in 1989 established the federal Agency for Healthcare Policy and Research (AHCPR), hoping that studies such as those on BPH would encourage a reduction in high-technology medicine and save money on medical costs, especially for Medicare and Medicaid. The agency was mandated to examine the reasons for the wide variations in healthcare practices around the country, develop guidelines for treatment, and find effective ways to disseminate its research findings and guidelines.25 However, the agency—and Congress—discovered to their surprise that the research results were not always welcome.

One of the health conditions that the AHCPR tackled early was low back pain. It is a widespread problem, ranking second only to the common cold as a reason that people go to the doctor. Treatment of back and neck problems cost over $80 billion in the United States in 2011.3 Surgery for low back pain is a high-variability procedure, ranging from a low in the Northeast to a rate in the Northwest that is more than three times higher. The guidelines developed by AHCPR’s panel of experts and released in December 1994 recommended treating most acute, painful low back problems with nonprescription painkillers and mild exercise, followed in about two weeks by conditioning exercises. Surgery benefits only about 1 in 200 people with acute low back problems, according to the chairman of the panel, a professor of orthopedic surgery at the University of Washington School of Medicine.26

Back surgeons responded with rage and political action. With the Republican Congress intent on budget cutting in 1995, legislators were sympathetic to claims by the back surgeons’ lobbying group that AHCPR was a waste of money, that the government should not be telling doctors how to practice medicine, and that the agency should be eliminated.27 Defenders of the AHCPR pointed out that the guidelines could save billions of dollars and accused back surgeons of merely trying to protect their incomes. When the federal budget was finally approved that year, AHCPR had survived, although its budget was cut substantially. Its leaders decided that developing clinical guidelines was too dangerous politically, but the agency continued collecting evidence that allowed other organizations to do so, and it maintains a national clearinghouse of evidence-based clinical guidelines developed by other organizations. A new emphasis on quality of care and patient safety was implemented, and the agency’s name was changed to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). Four years after its “near-death experience,” AHRQ had regained all the funding it lost, and the agency’s budget has held roughly steady at over twice this original level through 2015 (after accounting for inflation).28,29 Wennberg has argued for an expanded role for AHRQ, noting that outcomes research has the potential to restrain wasteful spending and could help to control costs.13

In fact, the federal government is increasingly interested in supporting comparative effectiveness research to evaluate the efficacy of competing drugs and to compare the effectiveness of different treatment options. For example, the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 allocated $1.1 billion to the AHRQ, the National Institutes of Health, and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services to conduct the research, and it also provided funds to the Institute of Medicine to recommend priorities for spending the money.30 The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 included the establishment of a Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute aimed at helping patients to make better-informed healthcare decisions.

As for treatment of low back pain, surgery rates in the Medicare population increased by 220 percent between 1988 and 2001, and the rates vary dramatically across geographic areas.31 To determine what an appropriate rate might be, a prospective study was conducted in Maine, where surgery rates were four times higher in some areas than in others. The researchers followed all patients who had surgery to see whether their symptoms improved after the operation. They found that the best outcomes occurred in the areas where the rates were lowest; and the worst outcomes occurred in the areas with the highest rates. The evidence suggested that surgeons in the low-use area used more stringent criteria for recommending surgery. In these areas, patients with more severe disease were more likely to benefit, and those with less severe disease avoided the risks of surgery, which are significant. The authors concluded: “Outcomes research has the potential to provide information that will enable each patient to better understand the outcomes, risks and benefits of an operation and other treatment.”32 (p.761) These findings may have contributed to the modest decline in back surgeries between 2001 and 2011.3

Quality

The AHCPR drama came at a time when there had been a series of highly publicized medical errors. A 39-year-old health reporter for the Boston Globe died after receiving an overdose of a chemotherapy drug while being treated for breast cancer at one of the most prestigious hospitals in the country. A 51-year-old diabetic man had the wrong leg amputated in a Florida hospital. And an 8-year-old boy in another Florida hospital died due to a drug mix-up during minor surgery.

A number of studies were published in the 1990s documenting that preventable medical errors occurred in 1.5 to 2 percent of hospitalizations, and that many of these errors caused the patient’s death. The Institute of Medicine (IOM) was asked to investigate the issue and recommend a strategy that would lead to improvements in quality of care. The study led to the publication in 1999 of a report, To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System.33 The report estimated that 44,000 to 98,000 deaths per year in the United States were caused by medical errors, more than motor vehicle accidents, breast cancer, or AIDS, placing medical errors among the top 10 causes of death.

Before the IOM report was published, medical errors were blamed on failures by individual doctors and nurses; practitioners who made mistakes were sued for malpractice, and some had even been prosecuted as criminals. The report shifted the blame to the medical care system—or nonsystem, according to some critics—characterizing it as decentralized and fragmented, rife with confusion, miscommunication, and lack of incentives for improvements in safety. The IOM committee compared the medical care industry unfavorably with other high-risk industries that had been much more successful at improving safety and preventing injury, especially the commercial airline industry. The report made a number of recommendations, beginning with the creation of a Center for Patient Safety within the AHRQ, which would set national goals, track progress, develop a research agenda, evaluate methods for identifying and preventing errors, and disseminate information. Another recommendation was that, as in the airline industry, accidents and near-misses should be reported so that errors could be investigated, leading to an understanding of the underlying factors that contribute to them. A mandatory, nonpunitive system should be developed that encourages providers to learn from their mistakes.34

Recognizing that many adverse events involve medication errors, the report recommended that the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) should require that drug naming, packaging, and labeling be designed to minimize confusion. Because of doctors’ notoriously poor handwriting, procedures should be developed to ensure accurate communication of prescriptions and other orders.

In 2009, Consumers Union (CU), the nonprofit agency that publishes Consumer Reports, published an evaluation of progress in implementing the IOM report’s recommendations ten years later.35 The report gave the country a failing grade in implementing procedures they believe necessary to create a healthcare system free of preventable medical harm. In particular, CU reported that few hospitals had adopted measures to prevent medication errors and that the FDA rarely intervened. Computerized prescribing and dispensing systems have not been widely adopted, despite evidence that they make patients safer. There is no national system of reporting medical errors and, where there is reporting, it is generally confidential, meaning that patients do not have access to information on how to compare the performance of doctors and hospitals, and there is little pressure for them to improve. Another IOM recommendation was to raise standards for competency of doctors, nurses, and other healthcare professionals by requiring them to periodically pass examinations demonstrating skills, knowledge, and use of best-practice care in order to maintain their certification. Most specialty boards now have this requirement but, according to the CU report, there is no mechanism in place to ensure the competency of the 15 percent of physicians not certified by one of these boards, as well as those “grandfathered” prior to the adoption of the standards.34

The CU report, as an example of medication errors, described the widely publicized incident in which the twin babies of actor Dennis Quaid and his wife were given 1000 times the prescribed dose of the blood thinner heparin because the different doses were packaged in similar vials with similar blue labels. The twins survived, but even though a similar mix-up had caused the deaths of three infants the previous year in an Indianapolis hospital, the packaging had not been changed.

An example of a system that works was part of a safety initiative in Michigan called the Keystone ICU project. The project was funded by the AHRQ and was instituted in 2004 in 103 Michigan intensive care units. One of the goals was to prevent some of the estimated 80,000 catheter-associated bloodstream infections and 28,000 deaths associated with these infections that occur in the United States each year. The intervention consisted of a short checklist of best practices related to catheter use; nurses were empowered to ensure that doctors were following these practices. Researchers tracked catheter-associated infections and found that the incidence dropped to less than 20 percent of what it had been before the procedures were implemented.36

The CU report argues that among the most important of the IOM recommendations is “increased accountability through mandatory, validated and public reporting of preventable medical harm, including healthcare-acquired infections.” According to the report, “It is a fundamental principle of quality control that if a process cannot be measured, it cannot be improved.”34 (p.6)

Medical Care Report Cards

The rise of managed care contributed to an increasing interest in the measurement of the quality and efficiency, or cost-effectiveness, of medical care. Managed care’s focus on cutting costs, however, conflicted with the common assumption that, when it comes to medical care, more is better—an assumption that is challenged by outcomes research that suggests that sometimes less may be better as well as less expensive.35 However, many people are suspicious that managed care companies, which have a financial incentive to do less for their patients, may have an inherent conflict of interest. The suspicion is especially strong in the case of for-profit managed care plans, which have an obligation to maximize profits for their investors, perhaps at the expense of the patients.

In the medical care marketplace, where economic factors are becoming increasingly significant, outcomes research has an important role to play in evaluating the quality and efficiency of different medical plans. In theory, when given enough information, customers—both the employers who choose which plans to offer and the employees who must choose among the plans that are offered—can make informed decisions, weighing quality and cost.37 Moreover, patients are increasingly becoming more active participants in their own care. In part because of growing distrust of the medical system, patients want information on risks and benefits of available treatments and, if possible, on the competence of their physicians and other medical providers. Outcomes research provides some of this information.

Although managed care is often regarded with skepticism, it is more easily evaluated than the traditional fee-for-service form of medical practice. The organization of services that allows care to be “managed” makes it possible for those services to be assessed in a formal way, something that is not realistic when each medical provider acts independently. Through an accreditation process conducted by the nonprofit National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA), it is possible to rate managed care plans on their performance with respect to a number of standards. Information on the accreditation status of a plan can influence a business’s decision about whether to offer the plan to its employees, and the information can be used by employees to choose among plans offered. In its 2014 State of Health Care Quality report, 1167 health plans covering 171 million Americans provided data to NCQA on 139 different measures of healthcare quality. NCQA reported that most of the health plans had improved on most of the measures. However, there was little recent progress on reducing overuse and inappropriate medical procedures.38 Consumers can access “report cards” of plans on the NCQA website and compare their performances.

Many of the most easily measured standards used by NCQA focus on preventive care: for example, whether children receive a full set of immunizations and whether women get mammograms and Pap tests. Other standards evaluate how a plan manages care for patients with common diseases. The findings of outcomes research can be used, for example, to measure performance of a health maintenance organization in treating elderly heart attack victims. Research supported by AHCPR found that patients 65 years of age and older were 43 percent less likely to die after a heart attack if they were treated with beta blockers than if they did not receive these drugs.39 Using that information, NCQA established, as one of its standards for evaluating a plan, the use of beta blockers for treatment of heart attacks. Since the agency began reporting on this measure, the percentage of heart attack patients who received the drugs went from 60 percent to well over 90 percent.40

Outcomes research can also be used in some circumstances to evaluate the performance of individual medical providers. The findings offer a basis not only for patients to choose where to go for treatment, but also for providers to compare their performance with that of their peers. Since 1989, New York State has measured the outcomes of coronary artery bypass surgery for treatment of blocked arteries in the heart, monitoring each of the hospitals where the operations are performed. Mortality rates in 1989, adjusted for patients’ risk factors such as age, diabetes, and hypertension, varied widely, from 0.88 percent to 10.02 percent.41 Data have also been collected on outcomes achieved by individual surgeons.

One of the study’s findings was that hospitals that perform large volumes of coronary surgery have better outcomes than those that perform few of the operations, a result that has also been found true of other types of surgery. The New York study also found that surgeons who perform more than 150 bypass operations per year have only half the patient mortality rate of surgeons who perform fewer than 50. The publicity that followed the release of the 1989 data on individual hospitals led to a dramatic decline (41 percent) statewide in mortality rates associated with the surgery over the next three years.42 Thus, the information provided by outcomes research led to improved quality of surgical care statewide. An analysis of how the improvements were accomplished show that hospitals identified as performing poorly reacted strongly, for example, by restricting the surgical privileges of some low-volume surgeons whose patients were more likely to die from the operation.43 Several other states including Pennsylvania, California, and Massachusetts now maintain similar datasets for coronary surgery in their hospitals.44

Despite the successes, health services research has a long way to go before it can be widely used to help people make decisions about health care based on quality. Most of the indicators of managed care quality measured by accrediting agencies focus on preventive care for the healthy. Although this approach is important from a public health perspective, what matters most to individual patients is the quality of care they receive when they are ill.33 Detailed analyses of providers’ performance are available for only a limited number of procedures in New York and the few other states that carry out such ambitious programs. The New York State Health Department publishes annual reports on its cardiac surgery data (available at http://www.health.state.ny.us/statistics/diseases/cardiovascular), and the data are increasingly being used: Managed care organizations are more likely to contract with surgeons who have lower risk-adjusted mortality rates, and surgeons who are rated poorly are more likely to discontinue performing the procedures.44

Inequities in Medical Care

Health services research has shed light on an unpleasant reality that pervades the American medical care system. Not only is care rationed by ability to pay, but there are racial inequities in how care is delivered even when individuals are able to pay for it. As documented in a 2002 IOM report, Unequal Treatment: What Healthcare Providers Need to Know About Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Healthcare,45 blacks and Hispanics are less likely than whites to receive the most effective treatments for heart disease, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, asthma, breast cancer, and many other conditions, even when their income and insurance status are equal to whites.

Regarding heart disease, for example, the work of the New York State researchers described above has also found racial differences in access to coronary artery bypass surgery. It seems that physicians are less likely to recommend surgery to patients from ethnic minority groups than to comparable white patients. Studying files of patients who had undergone diagnostic testing in eight New York hospitals, and using guidelines developed by the RAND Corporation for “appropriateness” and “necessity” of the operation, the researchers selected 1261 patients who would benefit from a coronary artery bypass. Returning to the files three months later, the researchers found that black and Hispanic patients were significantly less likely to have had the surgery than comparable white patients. It was not that the blacks and Hispanics had decided against the surgery; for the overwhelming majority, their physicians had not recommended it.46

Childhood asthma is a chronic disease that can usually be kept under control by providing patients and their families with prescriptions for inhaled medications and education on how to use them. A study that examined records of young children hospitalized for asthma found that racial minorities were less likely than whites to have taken the most effective medications before they were hospitalized and were less likely to be given prescriptions for such medications when they were discharged. Thus, black and Hispanic patients received poorer quality care than whites, an observation that was especially disturbing because the prevalence of asthma in minority children is higher than in whites—25 percent higher.47

According to the American Cancer Society, blacks have the highest death rate and the shortest survival of any racial and ethnic group in the United States for most cancers. Although the overall racial disparity in cancer death rates is decreasing, the death rate for all cancers combined is 32 percent higher in black men and 16 percent higher in black women than in white men and women, respectively.48 Blacks are less likely to survive five years after diagnosis, most likely due to a later stage at diagnosis, when the disease has spread. Blacks are also less likely to receive timely and high-quality treatment.

There are signs of promise in some areas and little progress in other areas. AHRQ’s National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Report, which has been provided to Congress annually since 2001, tracks disparities in healthcare access and quality across racial, ethnic, and economic groups.49 On the question of access to care, the report shows that the percentage of white adults ages 18–64 without health insurance continues to be much lower than the percentages for blacks and Hispanics, although this gap is shrinking. In 2010, 16.4 percent of whites were uninsured compared to 27.2 percent of blacks and 43.2 percent of Hispanics. By May 2014, 11.1 percent of whites were uninsured, while 15.9 percent of blacks and 33.2 percent of Hispanics were uninsured.49

As for quality of care, the report shows that the gap between whites and minorities has generally persisted. For example, in 2001, black smokers who had a medical checkup were less likely than white smokers to be given advice by a doctor on quitting smoking. By 2012, this gap between black and white smokers in what advice is provided had increased. On the other hand, when effective treatments have become widely adopted in the healthcare system, patients of all races and socioeconomic characteristics often benefit significantly. In some cases, the gap has disappeared almost entirely. One example is the rate at which heart attack patients receive a percutaneous coronary intervention to open a blocked artery (commonly called angioplasty) within 90 minutes of arriving to the hospital. In 2005, 29.1 percent of black patients received the procedure within 90 minutes, compared to 43.4 percent for whites. By 2012, 93.0 percent of blacks and 95.4 percent of whites received the procedure within 90 minutes.49

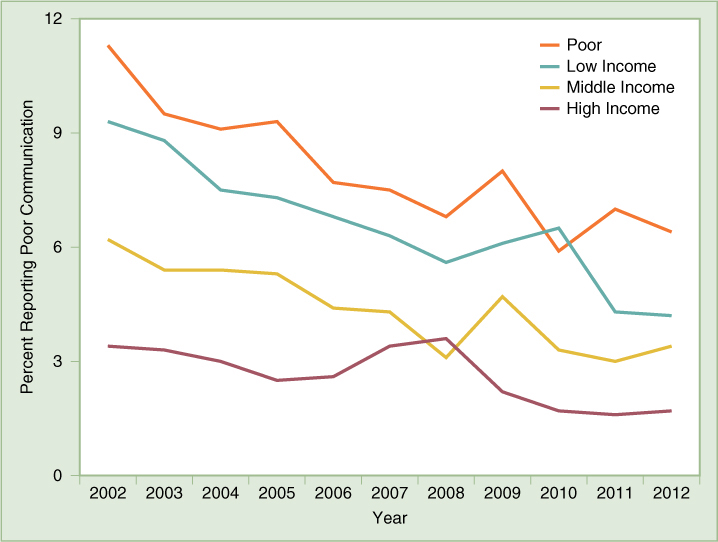

The report shows that the gap in healthcare quality is larger when measured along economic lines. Households below the poverty line receive worse care than high-income households on the majority of quality measures that are tracked in the National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Report, and better care on almost none of these measures. Worse, the overall gap increased between 2001 and 2012. Yet on some measures there have been modest improvements. (FIGURE 28-1) shows, by income group, the percentage of parents who report that their child’s health providers sometimes or never listened carefully, explained things clearly, showed respect for what they had to say, or spent enough time with them. The disparity in 2002 is striking, but by 2012 the differences in communication rates between income groups was beginning to compress as overall communication levels improved.49