- define health improvement, the determinants of health and the ethics of prevention;

- explain high-risk and population approaches to prevention;

- outline the roles of behaviour change, empowerment and social change in health improvement;

- outline key messages and actions for health improvement in medical practice.

What is health improvement and disease prevention?

Health is a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.

(World Health Organisation, 1946)

Health improvement is about preventing disease and death, and improving quality of life and well-being. Interventions can be implemented at different stages of the natural history of disease (see Table 19.1) and at individual, community and population levels to:

- Add years to life by reducing avoidable death;

- Add health to life by reducing disability and disease;

- Add life to years by enhancing quality of life.

Table 19.1 Different levels of prevention strategies.

Health promotion is the process of enabling people to increase control over, and to improve, their health.

(World Health Organisation, 1986)

Alongside this definition, the Ottowa charter for Health Promotion recommended:

- building healthy public policy – through legislation, fiscal measures, taxation and organisational change in all government policies;

- creating supportive environments – through physical and social living and working conditions that are safe and sustainable;

- strengthening community action – through empowerment and community development;

- developing personal skills – through provision of information, health education to support the personal and social development of individuals;

- reorienting health services – to broaden from curative medicine to the prevention of disease.

The ethics of health improvement

In 2007, the Nuffield Council on Bioethics proposed a stewardship model of public health that maintains ethically acceptable goals for preventative interventions including:

- promoting the health of children and other vulnerable people;

- helping people to overcome addictions and other unhealthy behaviours;

- ensuring that it is easy for people to lead a healthy life, for example by providing convenient and safe opportunities for exercise.

These goals must be tempered by recognition that preventative programmes should:

- not attempt to coerce adults to lead healthy lives;

- minimise interventions that are introduced without individual consent of those affected, or without a just mandate, such as democratic decision-making;

- seek to minimise interventions that are perceived as unduly intrusive and in conflict with important personal values.

To outweigh the adverse impact of state intervention on individual liberty, the justification for action must be stronger each step up the public health intervention ladder (see Box 19.1 and Table 15.1).

The determinants of health

Increasing the control people have over their health necessitates action to tackle the determinants of health. In 1974, the Lalonde report for the Canadian government argued that the health of individuals and society was determined by four major factors, or fields:

- genetics and biology;

- behaviour or lifestyle;

- physical and social environments;

- the organisation of health services.

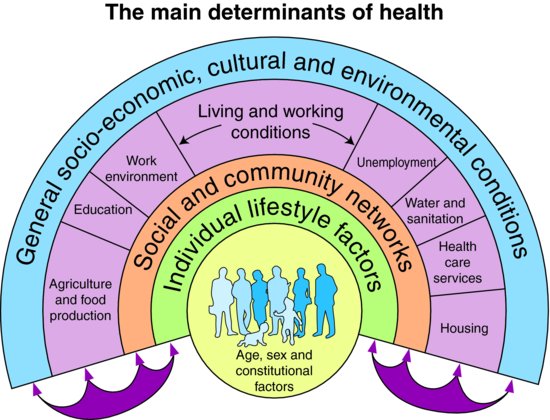

These fields are further illustrated by Whitehead and Dahlgren’s model of the social determinants of health:

The uneven distribution of the determinants of health across society leads to wide variation in the control individuals have over their health and this results in inequalities in health between groups.

The 2008 report of the WHO Commission on the Social Determinants of Health maintained that social inequalities in health come about through differential exposure to risk factors for, vulnerability to and consequences of disease. For example, economic recession commonly leads to higher levels of unemployment among manual and unskilled workers. Unemployment in turn leads to loss of self-esteem and social isolation, thus increasing vulnerability to depression. An unemployed, depressed person has less economic and social resources to cope with the consequences of this and other illnesses, leading to worse long-term prognosis and lower likelihood of returning to work.

The Commission recommended three principal actions to tackle the social determinants of health:

- Improve the conditions of daily life – the circumstances in which people are born, grow, live, work, and age.

- Tackle the inequitable distribution of power, money, and resources – the structural drivers of the conditions of daily life.

- Measure and understand the problem and assess the impact of action – using epidemiology to understand the problems and evaluate interventions.

Upstream determinants of health such as housing and economic conditions shape the distribution of downstream disease risk factors in the population. Health improvement policy typically addresses common ‘SNAP’ behavioural risk factors for disease in the population or individual: smoking; nutrition; alcohol, and physical activity. Clinical risk factor management in turn often targets reductions in biological risk markers linked to these behaviours.

High-risk and population approaches to prevention

There is a continuous distribution of many disease risk-factors in populations and therefore preventative interventions to reduce risk can be implemented across a whole population or targeted towards individuals or groups at particularly high risk. Geoffrey Rose observed that the relative merits of population and high risk strategies depends in large part upon the relationship between the exposure, such as serum cholesterol, blood pressure, alcohol or salt intake, and the outcome, such as coronary heart disease (CHD), stroke or chronic liver disease (Rose, 1981).

Where exposure to significant risk is limited to a small proportion of the population, a high-risk strategy will benefit the majority of individuals at risk and make a significant contribution to reduction in the total burden of disease. A high-risk approach has the advantages of a high benefit-to-risk ratio and clear patient and clinician motivation. Any individual at high risk of disease will benefit from targeted risk factor reduction in the clinical setting, regardless of the distribution of risk in the wider population.

In many circumstances, however, high-risk groups constitute a minority of the population and larger absolute improvements in population health can be made by reducing risk across the whole population. When an exposure is normally distributed in the population and the risk of disease by exposure approximately linear, then the majority of disease will occur among the ‘normal’ part of the population. This gives rise to the observation that ‘a large number of people at small risk may give rise to a larger number of cases of disease than the small number of cases who are at high risk’. In this context, a population approach will have the greatest impact on the total burden of disease as it reduces disease incidence in both high risk and ‘normal’ population sub-groups (see Figure 19.2).

Figure 19.1 Whitehead and Dahlgren model of health determinants.

Source: Dahlgren G, Whitehead M (1991) Policies and Strategies to Promote Social Equity in Health. Institute for Future Studies, Stockholm (Mimeo).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree