- to explain basic concepts of economics and how they relate to health;

- to distinguish the main types of economic evaluation;

- to understand the key steps in costing health care;

- to understand the Quality Adjusted Life Year (QALY) and its limitations;

- to interpret the results of an economic evaluation.

What is economic evaluation?

Economic evaluation is the comparison of the costs and outcomes of two or more alternative courses of action. If you bought this book, you have already conducted an informal economic evaluation. This involved comparing the cost of this book and the expected benefits of the information it contains against the cost and expected benefits of alternative books on the topic. In health, economic evaluation commonly compares the cost and outcomes of different methods of prevention, diagnosis or treatment.

The economic context of health care decisions

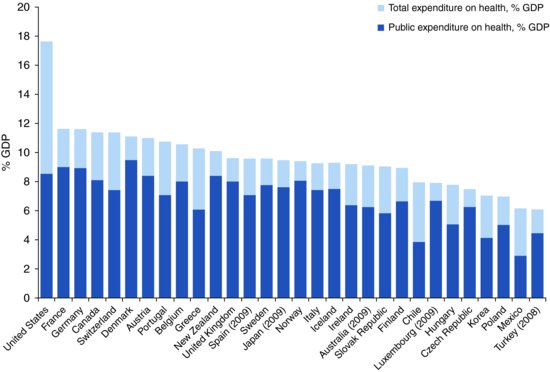

Higher income countries spend up to 16% of their wealth on health care. In the UK and Nordic countries the public purse pays for more than 80% of health expenditures, whereas in the United States and Switzerland the figure is closer to 50% (Figure 13.1). Funds are raised through general taxation or compulsory contributions by employers or individuals and are then used to pay for the care of vulnerable subgroups (e.g. the elderly and poor) or all citizens. For many of us, health care is free or heavily subsidised at the time of use. We never know its cost, and we do not consider whether it is public money well spent.

Figure 13.1 Total expenditure on health and public expenditure on health as % gross domestic product (GDP) in OECD countries in 2010. (When 2010 data were unavailable, previous years data were used as indicated in parentheses.)

Source: Based on data from OECD (2012) Total expenditure on health, Health: Key Tables from OECD, No. 1. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/hlthxp-total-table-2012-1-en and OECD (2012) Public expenditure on health, Health: Key Tables from OECD, No. 3. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/hlthxp-pub-table-2012-1-en.

Health care use is often initiated by a patient deciding to see a doctor. In a system with ‘free’ care, this decision can be based on medical and not financial considerations. This creates more equitable access; however it may lead to overuse of health services for trivial reasons, sometimes referred to as moral hazard. During the medical consultation, treatment decisions are often taken by the doctor with some patient input. Decisions should be based on sound evidence about treatment effectiveness for the patient (evidence-based medicine) and affordability for the population. In practice they may also be adversely influenced by incomplete evidence, commercial marketing, and even financial incentives if doctors are paid per procedure (sometimes referred to as supplier induced demand). By providing high-quality evidence on the costs and outcomes of alternative ways of providing health care, economic evaluation aims to improve the health of the population for any fixed level of public expenditure.

The design of an economic evaluation

Key elements of study design discussed in previous chapters also apply to economic studies. For example, a specification of the Patient group, Intervention, Comparator(s) and Outcome (PICO – see Chapter 8) is essential. In economic evaluation the outcome of interest is frequently expressed as a ratio, such as the additional cost per life year gained.

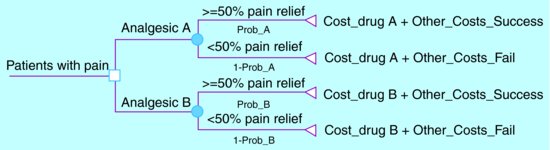

An economic evaluation conducted alongside a randomised controlled trial (RCT) would, typically, provide stronger evidence than an evaluation based on a cohort study. Regrettably, many RCTs do not include an economic evaluation, although regulators are increasingly demanding proof of efficiency before approval of new drugs and devices. In the absence of relevant information from RCTs, policy-makers rely on economic evidence generated by decision analysis models. These models define the possible clinical pathways resulting from alternative interventions (Figure 13.2) and then use literature reviews to draw together the best available evidence on the probability of each pathway, the expected costs and impact on patient health. Clearly these models are only as valid as the studies upon which they are based.

Figure 13.2 A simple decision analysis model to compare the cost effectiveness of two analgesics.

The probability of successful pain relief with drug A (Prob_A) and drug B (Prob_B) can be estimated from RCTs or the best available observational data. If economic data from an RCT are unavailable, the costs of prescribing drugs A and B (Cost_drugA and Cost_drugB) and the other costs of treating patients with successful (Other_Costs_Success) and unsuccessful (Other_Costs_Fail) pain relief can be estimated from observational studies. These six parameters allow estimation of the additional cost per patient with substantial pain relief of drug A versus drug B.

For example if: Prob_A = 0.75; Prob_B = 0.50; Cost_drugA = £100; Cost_drugB = £50; Other_Costs_Success = £20 and Other_Costs_Fail = £40, then the cost effectiveness of drug A versus drug B is:

[(£100 + (0.75)*£ 20 + (1 – 0.75)*£ 40) – (£ 50 + (0.50)*£ 20 + (1 – 0.50)*£ 40)]/(0.75 – 0.50)

This equates to £180 for every additional patient with substantial pain relief from drug A.

Efficiency is in the eye of the beholder

It is essential to consider the boundaries of the economic evaluation. A programme to prevent obesity in children is unlikely to appear cost-effective during the first few years, but may prove a wise investment over subsequent decades as the cohort develops fewer weight-related diseases. Therefore, for chronic diseases the appropriate time horizon for the economic evaluation is often the lifetime of the patient group. This has important implications for expensive new treatments where effectiveness can be proven relatively quickly by an RCT, but efficiency may not become apparent until long after the end of the RCT follow-up.

A natural starting point for an integrated health system is to ask whether the money it spends on a health technology is justified by the improvement it achieves in patient health. However, this health-system perspective may inadvertently lead to blinkered decision making, whereby costs are shifted onto other elements of society. For example centralisation of health care into larger clinics or hospitals might save the health system money at the expense of patients, carers and society through greater travel costs and more time off work. Given this, a strong argument can be made that, in making public spending decisions, we should take an all-encompassing (societal) viewpoint.

In everyday life, we are accustomed to thinking about costs in terms of monetary values. However money is just an imperfect indicator of the value of the resources used. For example, a doctor-led clinic-based routine follow-up of women with breast cancer could be replaced with a nurse-led telephone based approach. The financial cost of the doctor-led clinics may be no higher than the nurse-led telephone follow-up if the clinics are of short duration and conducted by low-salaried junior doctors. However, the true opportunity cost of the doctor led clinics may be much higher if these routine follow-up visits are preventing other women with incident breast cancer receiving prompt treatment at the clinic. The concept of opportunity cost acknowledges that the true cost of using a scarce resource in one way is its unavailability to provide alternative services.

How much does it cost?

The costing process involves identification of resource items affected by the intervention, measurement of patient use of these items and valuation to assign costs to resources used. Identification is governed by the chosen perspective of the analysis. From a health system perspective, an evaluation of a new drug for multiple sclerosis would go no further than tracking patient use of community, primary and secondary care health services. A broader societal perspective would require additional information on lost productivity due to ill health, care provided by friends and family and social services, and patient expenses related to the illness (e.g. travel to hospital, purchase of mobility equipment).

The introduction of electronic records has greatly increased the potential to use routinely collected data to measure resources (e.g. tests, prescriptions, procedures) used in hospitals and primary care. However, there are drawbacks. Records are often fragmented across different health system sectors and difficult to access. Records are usually established for clinical and/or payment purposes rather than research and therefore may not contain sufficient information for accurate costing. Therefore, patient self-report in the form of questionnaires or diaries is often used, but may be affected by loss to follow-up and recall bias. The degree of detail required for costing will vary. A study evaluating electronic prescribing would require direct observation of the prescription process. In other studies such minute detail on the duration of a clinic visit would be unnecessary.

Many health systems publish the unit costs of health care, for example the average cost of a MRI scan of the spine, which can be used to value the resources used by patients. However, in an RCT comparing rapid versus conventional MRI of the spine an average cost would not be sufficient and a unit cost must be calculated from scratch. This would include allocating the purchase cost of the imaging equipment across its lifetime (annuitisation) and apportioning salaries, maintenance, estate and other costs to every minute of machine use. It is particularly difficult to generalise the valuation of resource use between nations. General practitioners in the United States, United Kingdom and the Netherlands are paid up to twice as much as their counterparts in Belgium and Sweden, even after adjusting for the cost of living.

Is it worth it?

The typical goal of an intervention is to use resources to optimise health measured by clinical outcomes such as mortality or bone density, or patient-reported outcomes such as pain or quality of life (known as technical efficiency). If one outcome is of overriding importance then a Cost Effectiveness Analysis (CEA) (Table 13.1) could be used to summarise whether any additional costs of the intervention are justified by gains in health. For example an evaluation of acupuncture versus conventional care for patients with pain could calculate the extra cost per additional patient who has a 50% reduction in pain score at 3 months. If more than one aspect of health, for instance pain and function, are considered important outcomes of treatment, analysts can choose to simply tabulate the costs and all outcomes in a Cost Consequences Study (CCS). In a CCS, the reader is left to weigh up the potentially conflicting evidence on disparate cost and outcomes to reach a conclusion about the most efficient method of care.

Table 13.1 Types of economic evaluation.

| What outcome(s) are used | How are results presenteda | |

| Cost-effectiveness analysis | A primary physical measure e.g. 50% reduction in pain score | Extra cost per extra unit of unit of primary outcome measure |

| Cost consequences study | More than one important outcome measure e.g. 50% reduction in pain score, 50% increase in mobility score and patient satisfaction score | Costs and outcomes are presented in tabular form with no aggregation |

| Cost benefit analysis | Money | Benefit–cost ratio of intervention. |

| Cost utility analysis | QALYs | Extra cost per QALY gained |

| aif no intervention is dominant. | ||

Less frequently, analysts use Cost Benefit Analysis (CBA) to place a monetary value on treatment programmes. This is simplest in areas where citizens are familiar with paying for care. For example, people who might benefit from a new type of In Vitro Fertilisation (IVF) could be asked how much they would be willing to pay (WTP) for a cycle of this therapy, based on evidence that it increases the chances of birth from 20% to 30%. If the WTP of those who might benefit is greater than the additional costs of this new type of IVF, then this provides evidence that it is an efficient use of health care resources.

Policy-makers aim to create a health care system that is both technically and allocatively efficient. This means that money spent on each sector of care (e.g. oncology, orthopaedics or mental health) would not result in more health benefits if reallocated elsewhere in the health system. These allocative comparisons would be aided by a universal outcome measure. This measure needs to be flexible enough to be applicable in trials with outcomes as diverse as mortality, depression, and vision. Quality Adjusted Life Years (QALYs) used in Cost-Utility Analysis (CUA) aim to provide such a universal measure (see Table 13.1 which compares the 4 different types of analysis)

What is a QALY?

QALYs measure health outcomes by weighting years of life by a factor (Q) that represents the patient’s health-related quality of life. Q is anchored at 1 (perfect health) and 0 (a health state considered to be as bad as death) and is estimated for all health states between these extremes and a small number of health states that might be considered worse than death. A QALY is simply the number of years that a patient spends in each health state multiplied by the quality of life weight, Q, of that state. For example, a patient who spends 2 years in an imperfect health state, where Q = 0.75, would achieve 1.5 QALYs (0.75 × 2). Q is generally estimated indirectly via a questionnaire such as the EQ-5D. The questionnaire asks the patient to categorise current health in various dimensions – for example, mobility, pain, and mental health. Every possible combination of questionnaire response is given a quality weight, Q. These weights are derived from surveys of the public’s valuations for the health states described by the questionnaire.

There are concerns that in the attempt to measure and value a very broad range of dimensions of health, QALY questionnaires such as the EQ-5D have sacrificed responsiveness to small but important changes within an individual dimension. Additionally, there is disagreement about the appropriate group to use in the valuation survey. Should it be the general population who can take a dispassionate, but perhaps ill-informed, approach to valuing ill health? Or should it be patient groups who have experienced the health state? Perhaps the most persistent question about QALYs is whether they result in fair interpersonal comparisons of treatment effectiveness. The CUA methodology typically does not differentiate between a QALY resulting from treatment of a congenital condition in a child and a QALY resulting from palliative care in an elderly patient with a terminal illness. It is debatable whether this neutral stance reflects public opinion. For these and other reasons, QALYs remain controversial; in the UK they currently play an important role in national health care decision making, whereas in Germany their role is less prominent.

What are the results of an economic evaluation?

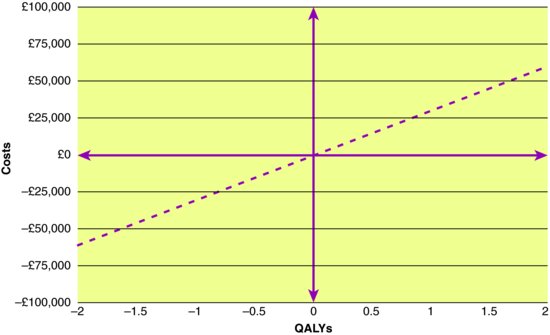

In essence, there are only four possible results from an economic evaluation of a new intervention versus current care (Cost Effectiveness Plane (CEP); (Figure 13.3)). Many new drugs are in the North East (NE) quadrant; they are more expensive, but more effective than existing treatment options. But that need not be the case. ‘Breakthrough’ drugs (e.g. Penicillin) can be both effective and cost saving (i.e. dominant in the South East quadrant) if the initial cost of the drug is recouped through future health care avoided. When the most effective intervention is simply not affordable, policy makers may opt for an intervention in the South West quadrant which is slightly less effective but will not bankrupt the health system. Sadly, the history of medicine also has a number of examples of new technologies (e.g. Thalidomide for morning sickness) that fall into the North West quadrant, more costly and eventually seen to be harmful (i.e. dominated). Most controversy and headlines in high-income countries concern interventions in the NE quadrant. Can public funds afford to pay for all health care that is effective, no matter how expensive or marginally effective it is? Assuming that the answer is no, then one solution for differentiating between more efficient and less efficient innovations would be to define a cost-effectiveness threshold. For example, the UK Government has indicated that it is unwilling to fund interventions that yield less than one QALY per £30,000 spent (i.e. anything above and to the left of the dashed line in Figure 13.3).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree