Headache Disorders

KEY CONCEPTS

![]() Acute migraine therapies should provide consistent, rapid relief and enable the patient to resume normal activities at home, school, or work.

Acute migraine therapies should provide consistent, rapid relief and enable the patient to resume normal activities at home, school, or work.

![]() A stratified care approach, in which the selection of initial treatment is based on headache-related disability and symptom severity, is the preferred treatment strategy for the migraineur.

A stratified care approach, in which the selection of initial treatment is based on headache-related disability and symptom severity, is the preferred treatment strategy for the migraineur.

![]() Strict adherence to maximum daily and weekly doses of antimigraine medications is essential.

Strict adherence to maximum daily and weekly doses of antimigraine medications is essential.

![]() Preventive therapy should be considered in the setting of recurring migraines that produce significant disability; frequent attacks requiring symptomatic medication more than twice per week; symptomatic therapies that are ineffective or contraindicated, or produce serious side effects; and uncommon migraine variants that cause profound disruption and/or risk of neurologic injury.

Preventive therapy should be considered in the setting of recurring migraines that produce significant disability; frequent attacks requiring symptomatic medication more than twice per week; symptomatic therapies that are ineffective or contraindicated, or produce serious side effects; and uncommon migraine variants that cause profound disruption and/or risk of neurologic injury.

![]() The selection of an agent for headache prophylaxis should be based on individual patient response, tolerability, convenience of the drug formulation, and coexisting conditions.

The selection of an agent for headache prophylaxis should be based on individual patient response, tolerability, convenience of the drug formulation, and coexisting conditions.

![]() Each prophylactic medication should be given an adequate therapeutic trial (usually 6 months) to judge its maximal efficacy.

Each prophylactic medication should be given an adequate therapeutic trial (usually 6 months) to judge its maximal efficacy.

![]() A general wellness program and avoidance of headache triggers should be included in the management plan.

A general wellness program and avoidance of headache triggers should be included in the management plan.

![]() After an effective abortive agent and dose have been identified, subsequent treatments should begin with that same regimen.

After an effective abortive agent and dose have been identified, subsequent treatments should begin with that same regimen.

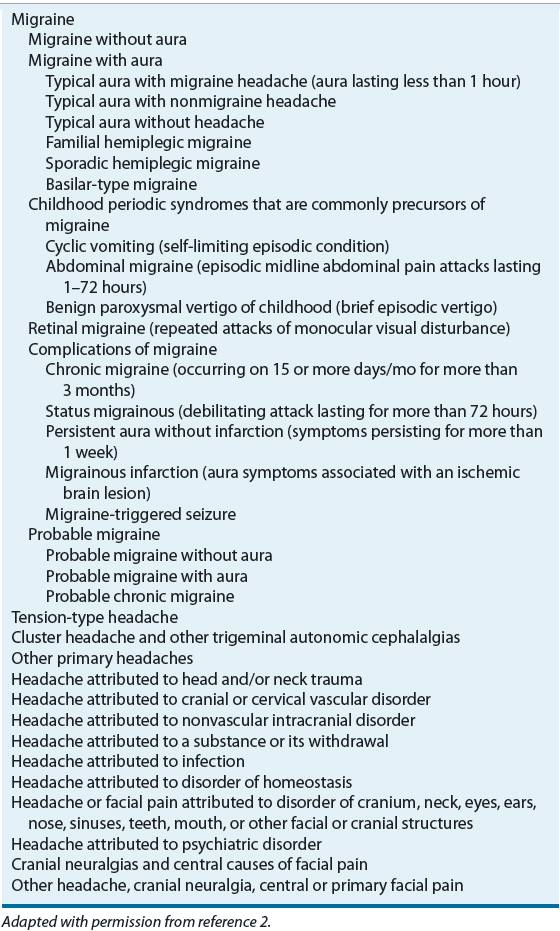

Headache is one of the most common complaints encountered by healthcare practitioners and among the top three principal reasons given by adults 18 years of age and over for visiting U.S. emergency departments.1 It can be symptomatic of a distinct pathologic process or can occur without an underlying cause. In 2004, the International Headache Society (IHS) updated its classification system and diagnostic criteria for headache disorders, cranial neuralgias, and facial pain2 (Table 45-1). Designed to facilitate headache diagnosis in clinical practice and research, the IHS classification provides more precise definitions and standardized nomenclature for both the primary (tension-type, migraine, and cluster headache) and secondary (symptomatic of organic disease) headache disorders. This chapter focuses on the management of the primary headache disorders.

TABLE 45-1 International Headache Society Classification System: Focus on Migraine Headache

Most recurrent headaches are the result of a benign chronic primary headache disorder.3 Less often, headaches are symptomatic of a serious underlying medical condition, such as infection, cerebral hemorrhage, or brain mass lesion. The peak prevalence of tension-type and migraine headache, the most common of the primary headache disorders, occurs during the most productive years of life (18 to 59 years of age).3,4 Despite the prevalence of these disorders and their associated disability, studies indicate that most headache sufferers do not seek appropriate medical care for their headaches.4,5 An improved understanding of the diagnosis and pathophysiologic mechanisms of the primary headache disorders, particularly migraine, has led to the development of medications capable of providing rapid relief from moderate to severe attacks. However, a thorough evaluation of the headache history is essential to establish an accurate headache diagnosis and identify patients who can benefit from these specific therapeutic options.

MIGRAINE HEADACHE

Epidemiology

Results of the American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention Study indicate that 17.1% of women and 5.6% of men in the United States experience one or more migraine headaches per year. The prevalence of migraine varies considerably by age and gender, but the epidemiologic profile has remained stable over the past 15 years. After age 12, females are two to three times more likely than males to suffer from migraine. Gender differences in migraine prevalence have been linked to menstruation, but these differences persist beyond menopause. Prevalence is highest in both men and women between the ages of 30 and 49 years.4 In the American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention Study, 93% of those with migraine reported some headache-related disability, and 54% were severely disabled or needed bedrest during an attack.4 A number of neurologic and psychiatric disorders as well as cardiovascular diseases, including stroke, epilepsy, major depression, sleep apnea, obesity, and anxiety disorder, show increased comorbidity with migraine.5–7 Whether this relationship is causal or representative of a common pathophysiologic mechanism is unknown. The economic burden of migraine is substantial; however, the indirect costs from work-related disability far exceed the direct costs associated with treatment.7,8

Etiology and Pathophysiology

The etiologic and pathophysiologic mechanisms of migraine are not completely understood. According to earlier theories, the migraine aura was caused by intracerebral arterial vasoconstriction followed by reactive extracranial vasodilation and associated headache. Studies of regional blood flow in the brain do not support this hypothesis, and previous vascular and neural theories of migraine development have merged into a combined theory of neurovascular mechanisms. Most clinicians now believe that the pathogenesis of migraine may be related to complex dysfunctions in neuronal and broad sensory processing.2,5,9

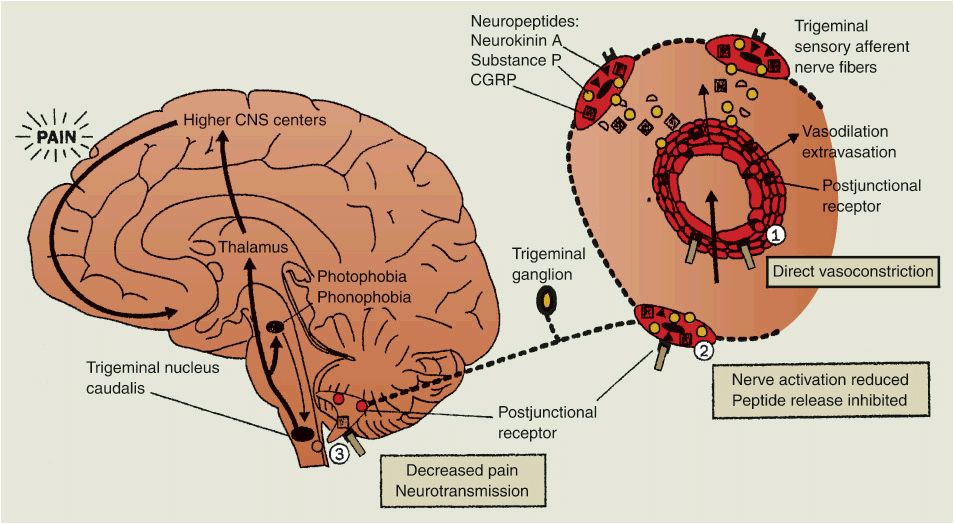

The pain and symptoms of migraine may be understood as a combination of altered perceptions resulting from neural suppression and activation of subcortical structures and trigeminal systems. Migraine pain is believed to result from activity within the trigeminovascular system, a network of visceral afferent fibers that arises from the trigeminal ganglia and projects peripherally to innervate the pain-sensitive intracranial extracerebral blood vessels, dura mater, and large venous sinuses10 (Fig. 45-1). These fibers also project centrally, terminating in the trigeminal nucleus caudalis in the brain stem and upper cervical spinal cord, and thus provide a pathway for nociceptive transmission from meningeal blood vessels into higher centers of the CNS. Activation of trigeminal sensory nerves triggers the release of vasoactive neuropeptides, including calcitonin gene–related peptide (CGRP), neurokinin A, and substance P, from perivascular axons. The released neuropeptides interact with dural blood vessels to promote vasodilation and dural plasma extravasation, resulting in neurogenic inflammation. Orthodromic conduction along trigeminovascular fibers transmits pain impulses to the trigeminal nucleus caudalis, where information is relayed further to higher cortical pain centers. Continued afferent input can result in sensitization of these central sensory neurons, producing a hyperalgesic state that responds to previously innocuous stimuli and maintains the headache.5,9–11

FIGURE 45-1 The pathophysiology of migraine headache. Vasodilation of intracranial extracerebral blood vessels (possibly the result of an imbalance in the brain stem) results in the activation of the perivascular trigeminal nerves that release vasoactive neuropeptides to promote neurogenic inflammation. Central pain transmission may activate other brain stem nuclei, resulting in associated symptoms (nausea, vomiting, photophobia, phonophobia). The antimigraine effects of the 5-HT1B/ID receptor agonists are highlighted at areas 1, 2, and 3. (CGRP, calcitonin gene–related peptide.)(Reprinted from reference 10, Copyright © 1998, with permission from Elsevier.).

Aura occurs in a subgroup of migraineurs and also with the other primary headache disorders. The neurologic changes of the aura parallel those that occur during cortical spreading depression, a neuronal event characterized by a wave of depressed electrical activity that advances across the brain cortex at a rate consistent with the spread of aura symptoms.5,9 Cortical spreading depression can cause inflammation and activation of the trigeminal nucleus caudalis. It is not clear whether this cortical spreading depression and the aura are the substrate of pain or actually trigger the presentation of migraine.5,11

Genetic factors seem to play an important role in susceptibility to migraine attacks. Studies in monozygotic twins suggest approximately 50% heritability of migraine with a multifactorial polygenic basis.12 Although it is possible for any individual to experience a migraine attack, it is recurrence in the migraineur that is abnormal. Attack occurrence and frequency are governed by CNS sensitivity to migraine-specific triggers or environmental factors. Migraineurs appear to have a lowered threshold of response to specific environmental circumstances as a result of genetic factors that govern the balance of CNS excitation and inhibition at various levels.12 Thus, trigger factors can be viewed as modulators of the genetic set point that predisposes to migraine headache. The hyperresponsiveness of the migrainous brain may be the result of an inherited abnormality in calcium and/or sodium channels and sodium/potassium pumps that regulate cortical excitability through the release of serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine [5-HT]) and other neurotransmitters. Increased levels of excitatory amino acids such as glutamate and alterations in levels of extracellular potassium also can affect the migraine threshold and initiate and propagate the phenomenon of cortical spreading depression.5,12,13

5-HT has long been implicated as an important mediator of migraine headache. Specific populations of 5-HT receptor subfamilies appear to be involved in the pathophysiology and treatment of migraine headache. Acute antimigraine drugs such as the ergot alkaloids and triptan derivatives are agonists of vascular and neuronal 5-HT1 receptor subtypes, resulting in vasoconstriction of meningeal blood vessels and inhibition of vasoactive neuropeptide release and pain signal transmission.5,14 Drugs used for migraine prophylaxis also modulate neurotransmitter systems.9 These actions and benefits in migraine management are consistent with the current understanding of migraine pathophysiology and neurovascular disorders.

Clinical Presentation

The migraine attack has been divided into several phases. Premonitory symptoms are experienced by 12% to 79% of migraineurs in the hours or days before the onset of headache.2,5,15 The previously popular terms prodrome and warning symptoms should be avoided because these are often used mistakenly to include aura.2 Premonitory symptoms vary widely among migraineurs but usually are consistent within an individual. Neurologic symptoms (e.g., allodynia, phonophobia, photophobia, hyperosmia, and difficulty concentrating) are common, but psychological (e.g., anxiety, depression, euphoria, irritability, drowsiness, fatigue, hyperactivity, and restlessness), autonomic (e.g., polyuria, diarrhea, and constipation), and constitutional (e.g., stiff neck, yawning, thirst, food cravings, and anorexia) symptoms also are reported.2,5,15

The migraine aura, a complex of positive and negative focal neurologic symptoms that precedes or accompanies an attack, is experienced by approximately 25% of migraineurs on some occasions.2,15 The aura typically evolves over 5 to 20 minutes and lasts less than 60 minutes. Headache usually occurs within 60 minutes of the end of the aura. Occasionally, aura symptoms begin at the onset of headache or during the attack. The aura is most often visual and frequently affects half the visual field.2 Visual auras vary in their complexity and can include both positive (scintillations, photopsia, teichopsia, or fortification spectrum) and negative (scotoma, hemianopsia) features. Sensory and motor aura symptoms, such as paresthesias or numbness involving the arms and face, dysphasia or aphasia, weakness, and hemiparesis, also are reported.2,15

CLINICAL PRESENTATION Migraine Headache

Of those with migraine in the United States, 14% experience more than four attacks per month, 63% experience one to four attacks per month, and 23% experience less than one attack per month.4 Migraine headache pain is usually gradual in onset, peaking in intensity over a period of minutes to hours and lasting between 4 and 72 hours. Pain can occur anywhere in the face or head but most often involves the frontotemporal region. The headache is typically unilateral and throbbing or pulsating in nature; however, pain can be bilateral at onset or become generalized during the course of an attack.2,15 GI symptoms almost invariably accompany the headache. During an attack, as many as 90% of migraineurs experience nausea, and emesis occurs in approximately one third of patients. Other systemic symptoms associated with the headache phase include anorexia, food cravings, constipation, diarrhea, abdominal cramps, nasal stuffiness, blurred vision, diaphoresis, facial pallor, and localized facial, scalp, or periorbital edema. Sensory hyperacuity, manifested as photophobia, phonophobia, or osmophobia, is reported frequently. Because headache pain usually is aggravated by physical activity, most migraineurs seek a dark, quiet room for rest and relief. Impaired concentration, depression, irritability, fatigue, or anxiety often accompanies the headache. Once headache pain wanes, patients may experience a resolution phase characterized by feeling tired, exhausted, irritable, or listless. Impaired concentration may continue, as well as scalp tenderness or mood changes. Some patients experience depression and malaise, whereas others can feel unusually refreshed or euphoric.2,15 The reader is referred to the IHS classification and recent reviews for descriptions of the classic migraine variants and other migraine subtypes2,15 (Table 45-1).

Although headaches have many potential causes, most are considered to be primary headache disorders. A comprehensive headache history is the most important element in establishing the clinical diagnosis of migraine.5,16 A thorough headache history always should be obtained, and information collected should include age at onset, attack frequency and timing, duration of attacks, precipitating or aggravating factors, ameliorating factors, description of neurologic symptoms, characteristics of the headache pain (quality, intensity, location, and radiation), associated signs and symptoms, treatment history, family and social history, and the impact of headaches on daily life.

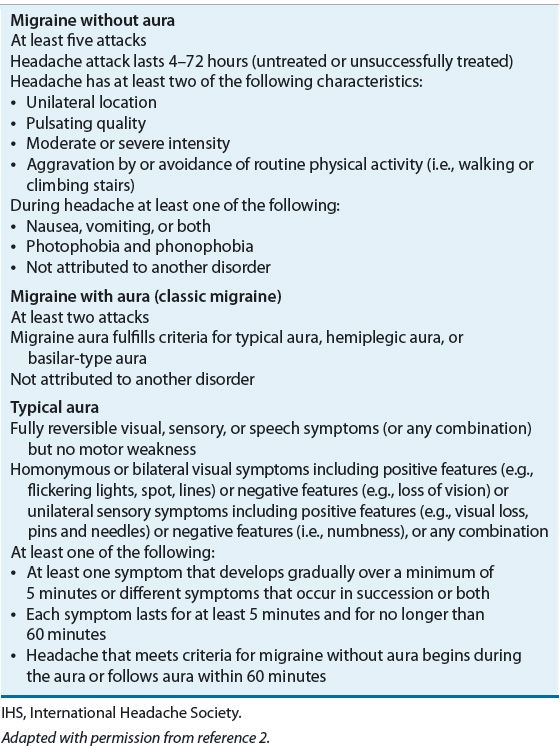

Secondary headache can be identified or excluded based on the headache history, as well as the results of general medical and neurologic examinations. Diagnostic and laboratory testing also can be warranted in the setting of suspicious headache features or an abnormal examination. The routine use of neuroimaging (computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging) generally is not indicated in patients with migraine and a normal neurologic examination, but should be considered in patients with an unexplained abnormal neurologic examination or an atypical headache history.2,3,15 Because migraine headaches usually begin by the second or third decade of life, headaches beginning after age 50 years suggest an organic etiology such as a mass lesion, cerebrovascular disease, or temporal arteritis. Table 45-2 lists the IHS diagnostic criteria for migraine with and without aura.2

TABLE 45-2 IHS Diagnostic Criteria for Migraine

TREATMENT

Migraines

Desired Outcome

Clinicians who care for migraineurs must appreciate the impact of this painful and debilitating disorder on the life of the patient, the patient’s family, and the patient’s employer. Treatment strategies must address both immediate and long-term goals.![]() Acute migraine therapies should provide consistent, rapid relief and enable the patient to resume normal activities at home, school, or work. Recurrence of symptoms and treatment-related adverse effects should be minimal. Ideally, patients should be able to manage their own headaches effectively without a medical visit. In addition, migraineurs should take an active role in the creation of a long-term formal management plan. An individualized approach to treatment can result in a reduction in attack frequency and severity, thus minimizing headache-related disability and emotional distress and improving the patient’s quality of life. Goals of long-term and acute treatment of migraine are listed in Table 45-3.14,16

Acute migraine therapies should provide consistent, rapid relief and enable the patient to resume normal activities at home, school, or work. Recurrence of symptoms and treatment-related adverse effects should be minimal. Ideally, patients should be able to manage their own headaches effectively without a medical visit. In addition, migraineurs should take an active role in the creation of a long-term formal management plan. An individualized approach to treatment can result in a reduction in attack frequency and severity, thus minimizing headache-related disability and emotional distress and improving the patient’s quality of life. Goals of long-term and acute treatment of migraine are listed in Table 45-3.14,16

TABLE 45-3 Goals of Therapy in Migraine Management

General Approach to Treatment

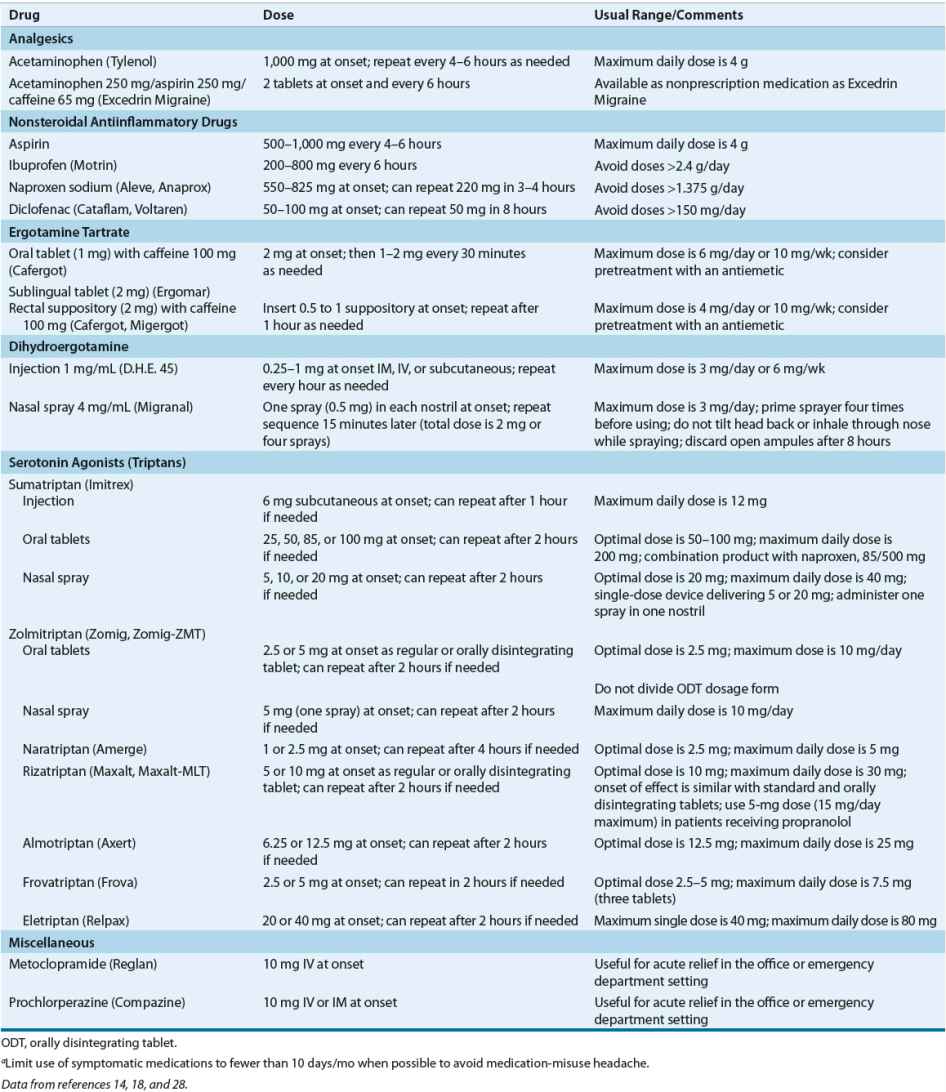

Nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic interventions are available for the management of migraine headache; however, drug therapy remains the mainstay of treatment for most patients. Pharmacotherapeutic management of migraine can be acute (i.e., symptomatic or abortive) or preventive (i.e., prophylactic). When choosing acute or preventive therapies, the clinician should consider the patient’s response to specific medications and their tolerability, as well as coexisting illnesses that can limit treatment choices. Abortive or acute therapies can be migraine-specific (e.g., ergots and triptans) or nonspecific (e.g., analgesics, antiemetics, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs [NSAIDs], and corticosteroids) and are most effective at relieving pain and associated symptoms when administered at the onset of migraine14,16,17 (Table 45-4). ![]() A stratified care approach in which the selection of initial treatment is based on headache-related disability and symptom severity is the preferred treatment strategy for the migraineur.14,16 Because attack severity varies in individuals, patients may be advised to use nonspecific agents for mild to moderate headache not causing disability while reserving migraine-specific medications for more severe attacks. The absorption and efficacy of orally administered drugs can be compromised by gastric stasis or nausea and vomiting that accompany migraine. Pretreatment with antiemetic agents or the use of nonoral treatment (e.g., suppositories, nasal sprays, or injections) is advisable when nausea and vomiting are severe.14,18

A stratified care approach in which the selection of initial treatment is based on headache-related disability and symptom severity is the preferred treatment strategy for the migraineur.14,16 Because attack severity varies in individuals, patients may be advised to use nonspecific agents for mild to moderate headache not causing disability while reserving migraine-specific medications for more severe attacks. The absorption and efficacy of orally administered drugs can be compromised by gastric stasis or nausea and vomiting that accompany migraine. Pretreatment with antiemetic agents or the use of nonoral treatment (e.g., suppositories, nasal sprays, or injections) is advisable when nausea and vomiting are severe.14,18

TABLE 45-4 Drug Dosing Table—Acute Migraine Therapiesa

The frequent or excessive use of acute migraine medications can result in a pattern of increasing headache frequency and drug consumption known as medication-overuse headache (or rebound headache).2,5,19 The syndrome appears to evolve as a self-sustaining headache–medication cycle in which the headache returns as the medication wears off, leading to the consumption of more drug for relief. The headache history often reflects the gradual onset of an atypical daily or near-daily headache with superimposed episodic migraine attacks. Medication overuse is one of the most common causes of chronic daily headache.19 Agents most commonly implicated in this syndrome include simple and combination analgesics and opiates. Triptans are also implicated but only in men with a high frequency of headaches.2,5,19 Discontinuation of the offending agent leads to a gradual decrease in headache frequency and severity and a return of the original headache characteristics. Although detoxification usually can be accomplished on an outpatient basis, hospitalization can be necessary for the control of refractory rebound headache and other withdrawal symptoms (e.g., nausea, vomiting, asthenia, restlessness, and agitation). ![]() Regulation of nociceptive systems and renewed responsiveness to therapy usually occur within 2 months following medication withdrawal.2 Most experts recommend limiting use of acute migraine therapies to fewer than 10 days per month to avoid the development of medication-misuse headache.20

Regulation of nociceptive systems and renewed responsiveness to therapy usually occur within 2 months following medication withdrawal.2 Most experts recommend limiting use of acute migraine therapies to fewer than 10 days per month to avoid the development of medication-misuse headache.20

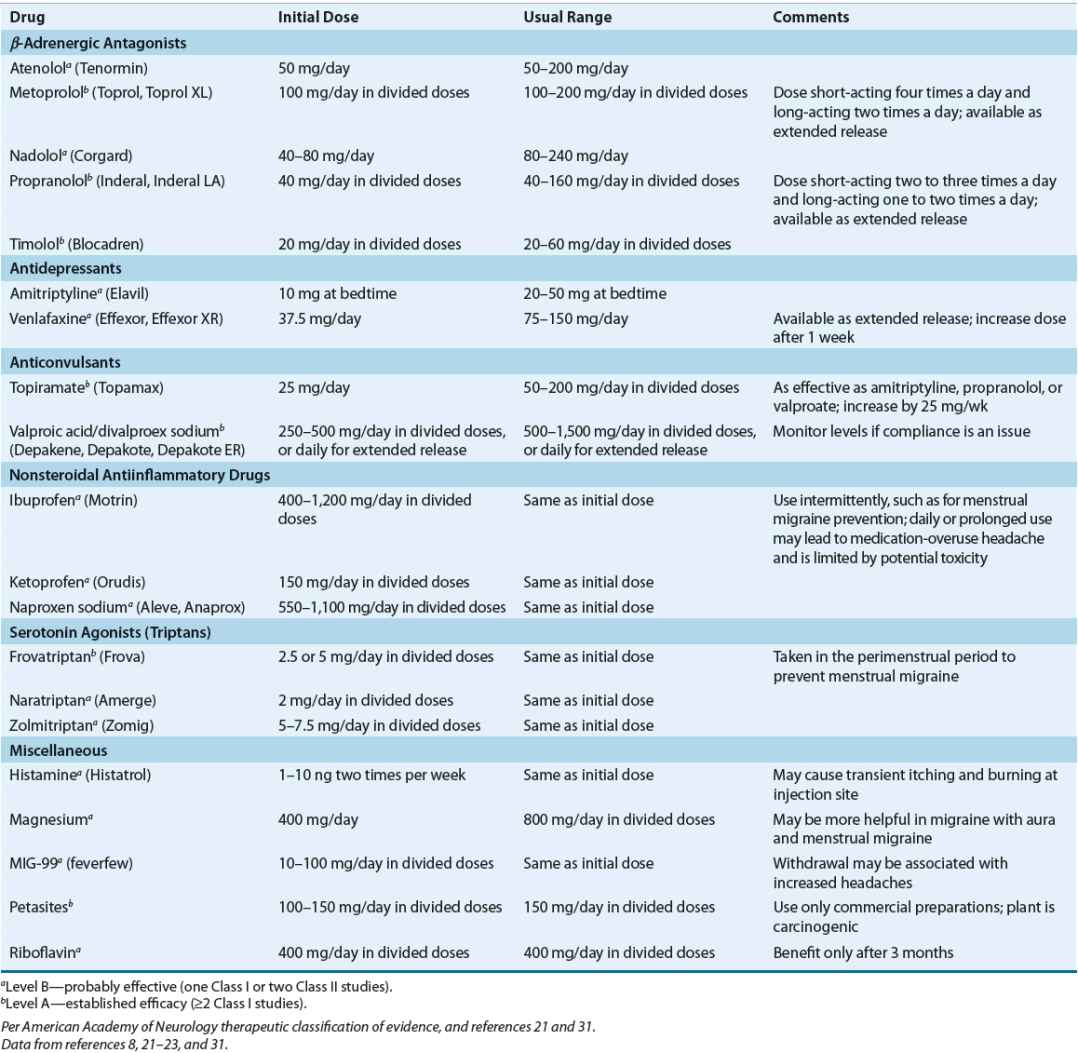

Preventive migraine therapies are administered on a daily basis to reduce the frequency, severity, and duration of attacks and improve responsiveness to symptomatic migraine therapies8,21,22 (Table 45-5).![]() Preventive therapy should be considered in the setting of recurring migraines that produce significant disability despite acute therapy; frequent attacks occurring more than twice per week with the risk of developing medication-overuse headache; symptomatic therapies that are ineffective or contraindicated, or produce serious side effects; uncommon migraine variants that cause profound disruption and/or risk of permanent neurologic injury (e.g., hemiplegic migraine, basilar migraine, and migraine with prolonged aura); and patient preference to limit the number of attacks.8,23 Preventive therapy also may be administered preemptively or intermittently when headaches recur in a predictable pattern (e.g., exercise-induced migraine or menstrual migraine).7 The evidence to support the various agents used for migraine prophylaxis has recently been reviewed. Only propranolol, timolol, divalproex sodium, and topiramate are currently approved by the FDA for the indication, although other agents have established or probable efficacy.

Preventive therapy should be considered in the setting of recurring migraines that produce significant disability despite acute therapy; frequent attacks occurring more than twice per week with the risk of developing medication-overuse headache; symptomatic therapies that are ineffective or contraindicated, or produce serious side effects; uncommon migraine variants that cause profound disruption and/or risk of permanent neurologic injury (e.g., hemiplegic migraine, basilar migraine, and migraine with prolonged aura); and patient preference to limit the number of attacks.8,23 Preventive therapy also may be administered preemptively or intermittently when headaches recur in a predictable pattern (e.g., exercise-induced migraine or menstrual migraine).7 The evidence to support the various agents used for migraine prophylaxis has recently been reviewed. Only propranolol, timolol, divalproex sodium, and topiramate are currently approved by the FDA for the indication, although other agents have established or probable efficacy.![]() Guidelines identify which agents might be effective, but there is insufficient evidence as to how to choose one therapy over another. Thus, the selection of an agent typically is based on its side effect profile and the patient’s coexisting/comorbid conditions.16,21

Guidelines identify which agents might be effective, but there is insufficient evidence as to how to choose one therapy over another. Thus, the selection of an agent typically is based on its side effect profile and the patient’s coexisting/comorbid conditions.16,21 ![]() A therapeutic trial of 2 to 3 months is necessary to achieve clinical benefit, but some reduction in attack frequency can be evident by the first month of therapy. Maximal benefits are typically observed by 6 months of treatment.7,8,21 Drug therapy should be initiated with low doses and gradually increased until a therapeutic effect is achieved or side effects become intolerable. Drug doses for migraine prophylaxis are often lower than those necessary for other indications.7,8 Overuse of acute headache medications will interfere with the effects of preventive treatment.16,19 Prophylactic treatment usually is continued for at least 6 to 12 months after the frequency and severity of headaches have diminished. After that time, based on discussions with the patient, gradual tapering or discontinuation may be reasonable.8,21 Many migraineurs experience fewer and less severe attacks for lengthy periods following discontinuation of prophylactic medications or taper to a lower dose. Figures 45-2 and 45-3 identify treatment and management algorithms for migraine headache.

A therapeutic trial of 2 to 3 months is necessary to achieve clinical benefit, but some reduction in attack frequency can be evident by the first month of therapy. Maximal benefits are typically observed by 6 months of treatment.7,8,21 Drug therapy should be initiated with low doses and gradually increased until a therapeutic effect is achieved or side effects become intolerable. Drug doses for migraine prophylaxis are often lower than those necessary for other indications.7,8 Overuse of acute headache medications will interfere with the effects of preventive treatment.16,19 Prophylactic treatment usually is continued for at least 6 to 12 months after the frequency and severity of headaches have diminished. After that time, based on discussions with the patient, gradual tapering or discontinuation may be reasonable.8,21 Many migraineurs experience fewer and less severe attacks for lengthy periods following discontinuation of prophylactic medications or taper to a lower dose. Figures 45-2 and 45-3 identify treatment and management algorithms for migraine headache.

TABLE 45-5 Drug Dosing Table—Prophylactic Migraine Therapies

FIGURE 45-2 Treatment algorithm for migraine headaches.

FIGURE 45-3 Treatment algorithm for prophylactic management of migraine headaches. (NSAID, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug.)

Nonpharmacologic Therapy

Nonpharmacologic therapy of acute migraine headache is limited but can include application of ice to the head and periods of rest or sleep, usually in a dark, quiet environment. Preventive management of migraine should begin with the identification and avoidance of factors that consistently provoke migraine attacks in susceptible individuals2,3,16,24 (Table 45-6). Changes in estrogen levels associated with menarche, menstruation, pregnancy, menopause, oral contraceptive use, and other hormone therapies can trigger, intensify, or alleviate migraine.7 A headache diary that records the frequency, severity, and duration of attacks can facilitate identification of migraine triggers. ![]() Patients also can benefit from adherence to a wellness program that includes regular sleep, exercise, and eating habits, smoking cessation, and limited caffeine intake. Behavioral interventions, such as relaxation therapy, biofeedback (often used in combination with relaxation therapy), and cognitive therapy, are preventive treatment options for patients who prefer nondrug therapy or when symptomatic therapies are poorly tolerated, contra-indicated, or ineffective.16

Patients also can benefit from adherence to a wellness program that includes regular sleep, exercise, and eating habits, smoking cessation, and limited caffeine intake. Behavioral interventions, such as relaxation therapy, biofeedback (often used in combination with relaxation therapy), and cognitive therapy, are preventive treatment options for patients who prefer nondrug therapy or when symptomatic therapies are poorly tolerated, contra-indicated, or ineffective.16

TABLE 45-6 Commonly Reported Triggers of Migraine