Headache

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

Headaches are very common, with over 95% of patients suffering from at least one headache in their lifetime. Between 250 and 800 workdays/1000 patients in the U.S. are lost due to headaches. Headaches can occur as part of a systemic illness, such as influenza, or as a single symptom. The International Headache Society classification system (ICHD-2) has over 150 pages of concise diagnostic criteria for different types of headaches. In the literature, headaches have been classified in a variety of ways. Primary headaches, the most common, include tension-type headaches, migraine headaches, and cluster headaches. Secondary headaches are by definition all nonprimary headaches and include those due to meningitis, hypertensive emergencies, strokes, temporomandibular joint (TMJ) pain dysfunction syndrome, trauma related, and pseudotumor cerebri. Others have classified them by seriousness or urgency. Acute onset headaches are mostly secondary, are more serious, and can be life threatening, requiring immediate diagnosis and intervention. Chronic or recurrent headaches, which include all the primary headaches and have a much more benign prognosis.

• ETIOLOGY

The causes of headache are multiple and at times complex in pathophysiology. Infectious processes, vascular problems, malignancy, medications, trauma, metabolic disorders, musculoskeletal problems, dental problems, diagnostic procedures, and hypoxia all are etiologic causes of headaches. Even among primary headaches, the exact cause of some may not be known or the exact nature of the pathophysiology is unclear and potentially controversial.

• DIAGNOSIS

There are several ways to classify headaches to facilitate diagnosis. For the purposes of this chapter, headaches will be organized as either primary or secondary.

• COMMON PRIMARY HEADACHES

The three main causes of a primary headache are tension-type headache, migraine headache, and cluster headache. While there are typical symptom patterns with each of the three primary headaches, initially it may be difficult to distinguish between severe tension headaches and some milder forms of migraines. Table 13.1 provides a quick guide to prominent features of the common primary headaches.

| TABLE 13.1 | Common Primary Headaches |

Tension-Type Headache

Tension headaches are the most common form of headache. Eighty-six percent (86%) of patients aged 12 to 41 have reported at least one tension headache during a 1-year period. The exact pathophysiology of tension headaches is still unclear. The current theory involves sensitization of dorsal horn neurons due to increased activity of the muscles and nerves in the neck, head, and shoulders.

Tension-type headaches typically present with mild-moderate pain intensity and are described as a bilateral, nonpulsating headache. The pain is constant and typically described as dull, pressure, vise-like, etc. Tension headaches are usually associated with muscle tenderness in the head, neck, and shoulders, which can be elicited by palpation of the muscles and rotation of the head and neck. Precipitating factors include stress, tension, and head/neck movements. Physical activity has little effect on the pain intensity. Neurological examination is normal and the overall physical examination is unremarkable except for some palpable muscle tenderness. Reasons for referral of tension headaches include more than 15/month, patients with increasing frequency of headaches, those that do not exactly fit the diagnostic criteria, or in whom standard treatments with analgesics are ineffective. Referral is necessary in these patients to eliminate secondary causes such as mass occupying lesions, medication overuse headache, or TMJ pain dysfunction syndrome.

Migraine Headache

Migraine headaches are the second most common primary headache with a prevalence of 23/1000 and they more commonly occur in women in a 3:1 ratio. There are 18 types and subtypes of migraine headaches listed in IHCD-2. The two most common are migraines without aura or common migraines (64%), and migraine with aura or classic migraines (18%). At times, the diagnosis of migraine can be difficult. In one study, 98% of patients with sinus headaches actually had migraine or probable migraine headaches. Regardless of the presence of aura, migraines present with moderate to severe pain that is incapacitating, unilateral, pulsating, or throbbing and is made worse by physical activity. In addition, patients may experience nausea, vomiting, photophobia, or phonophobia. ICDH-2 requires that patients meet two of the four initial criteria and during the headache experience one of the second group of symptoms for the diagnosis of migraine headaches. Ten to thirty percent of patients will have an aura before and/or during the headache, which may consist of flashing lights, scotoma, visual disturbances, paresthesias, or a prodrome of tiredness, fatigue, mood changes, or gastrointestinal symptoms. One of the reasons for the structure of the ICDH-2 migraine criteria is that 20% to 30% of patients with migraines do not experience each of the typical symptoms, i.e., unilateral, pulsating, photophobia, phonophobia, and nausea. Migraine headaches typically last 4 to 72 hours. Many times patients may require a neurologist who specializes in headaches to accurately diagnose and effectively treat migraine headaches. A neurological examination will be normal.

The etiology of migraine headaches has remained controversial for decades. There may be multiple causes that explain the variety of presentations and individual responses to different preventive and treatment regimens. The old theory was that changes in neurotransmitter activity in the brain lead to a vasoconstriction followed by rebound vasodilation in intra- and extracranial blood vessels, which causes headache. While there is evidence to support this older model, most experts now feel that migraines are a gene-based disease, because there is a close family history of migraine headaches found in over 70% of patients newly diagnosed. In these patients, dysfunction in the periaqueductal gray matter causes the loss of inhibition over the cortex of the brain. This results in an electrical wave that causes trigeminovascular neuronal hyperreactivity involving decreased or destabilized serotonin activity in the brain stem. This leads to the release of inflammatory, vasodilator neuropeptides such as CGRP (calcitonin gene-related peptide), PACAP (pituitary adenylate cyclase activating peptide), and nitric oxide (NO). Those neuropeptides cause an inflammation of the vessels and tissue in the midbrain that leads to the pain and eventual vasodilation. Current research efforts are developing drugs that block the activity/release of each of these inflammatory mediators.

Cluster Headache

The last major primary headache, the cluster headache, is relatively uncommon, with a prevalence of 0.5 to 1.0/1000 patients. It occurs primarily in men in a ratio of 5:1. Cluster headaches present with severe pain (worse than migraine pain) in the orbital, supraorbital, or temporal region that is unilateral and pulsating, lasting 30 to 180 minutes if untreated. In addition, attacks occur in clusters from once every other day to eight times/day with headache-free periods lasting days to months. To diagnose cluster headaches, patients must have one or more autonomic symptoms ipsilateral (same side) to the location of the pain. These include nasal congestion or rhinorrhea, conjunctival injection (redness) or lacrimation, miosis and/or ptosis, forehead and/or facial sweating, or eyelid edema. Other than the eye findings, a neurological examination will be normal. Patients with cluster headaches need to be seen by a neurologist or headache specialist for management.

• SECONDARY HEADACHES

Secondary headaches usually have more serious consequences that require immediate intervention. Any patient presenting with what seems like a primary headache but has an abnormal neurological examination requires a workup for a secondary headache. New headaches in patients over 50 or any severe headache requires immediate further diagnostic testing. CT scans are the initial choice and are accurate in identifying acute hemorrhage, trauma to bony structures, and sinus disorders. MRIs are used to rule out infarction, mass occupying lesions, brain abscesses, and craniocervical junction abnormalities. Recently, one author updated a mnemonic for secondary headaches called SNOOP 4. S stands for systemic and includes immunosuppressed patients, infectious meningitis, brain abscess, and metastatic tumor. N indicates neurologic abnormality, which would relate to infarcts or mass occupying lesions. The first O is for sudden onset that indicates cerebrovascular accident (CVA), subarachnoid hemorrhage, or arterial dissection. The second O is for onset of new headache over age 50, which considers temporal arteritis, neoplastic, or vascular issues. Finally, P stands for pattern change with 4 potential causes including progressive headache and papilledema. For the pharmacist, other than tension headaches, patients should be referred for definitive diagnosis and treatment.

Temporomandibular Joint Dysfunction Syndrome

One of the symptoms of TMJ dysfunction can be a headache. Initially, because of associated myofascial pain in some patients it was thought that it caused tension headaches. However, recent literature shows a much stronger link with migraine headaches and chronic daily headaches than tension headaches.

Suspicion of TMJ disorders as a cause of headache can be confirmed with a careful history and limited physical examination. Place the palmar surface of the fingers of both hands over each TMJ. Have the patient open their mouth wide. A palpated clicking sensation or audible click confirms the potential for a TMJ disorder. In addition, simultaneously observe the opening and closing of the mouth. Normally, the jaw opens vertically straight up and down. Any jerky, sideways or angled movement during opening and/or closing may be indicative of TMJ disorder. Patients with TMJ disorder headaches commonly will awaken with their headache and many have a history of bruxism (grinding the teeth at night) or regular jaw clenching. Many patients have occlusal disorders with underbites more common than overbites. In some patients chewing gum is associated with the headache. Patients suspected of headaches secondary to TMJ disorders should be referred to a dentist initially for evaluation of TMJ disorders.

Medication Overuse/OTC Headaches

Medication overuse headache is a relatively new entity. While it occurs in patients with both tension and migraine headaches, patients with episodic migraines and women are the most frequent patients to develop this type of headache. There are three criteria for diagnosis. The first is a chronic daily headache for more than 15 days/month. The second criteria is a 3-month overuse of ergotamine, triptans, opioids, or combination analgesics (including those with butalbital) for more than 10 days/month. Alternatively analgesics or any combination of ergots, triptans, opioid analgesics for more than 15 days/month without overuse also meet the criteria. Finally, there must be a history of recent development or markedly worsened headache during medication overuse. Patients who you suspect of this problem should be referred to a neurologist or headache specialist for diagnosis and treatment. Treatment involves tapering the causative medication or discontinuing it while providing other medication for pain relief. Elimination or marked reduction in headache frequency after 60 days is diagnostic.

Hypertensive Emergency (Malignant Hypertension)

Patients who present with blood pressures >220/120 are at risk for hypertensive encephalopathy, as well as intracranial and subarachnoid hemorrhages. Patients with all three conditions can present with a moderate to severe headache. In hypertensive encephalopathy, cerebral edema occurs, causing the headache and potential changes in behavior and cognitive function. Funduscopic examination of the eye many times reveals papilledema, a swelling and blurring of the optic disc. Treating the blood pressure reduces the risk of those complications and the patient’s symptoms including the headache.

Tumor/Mass Occupying Lesion

Tumors of the brain can be either malignant or nonmalignant. Also, they can be primary tumors or metastatic lesions from a primary cancer elsewhere in the body. Patients previously diagnosed with other malignancies that may metastasize to the brain who present with a headache should be immediately referred to their oncologist for further diagnostic evaluation. Headaches, cognitive decline, or behavior changes with focal neurologic deficits are typical presentations. Some tumors such as benign meningiomas are diagnosed during evaluation of a primary headache and can be an incidental finding. Regardless, unexplained headaches, progressive headaches, or new headaches with or without neurological deficits should be immediately referred to a neurologist or headache specialist for further evaluation

Meningitis

Meningitis can be caused by a variety of microorganisms including bacteria, viruses, fungi, and mycobacteria.

Viral meningitis, also known as aseptic meningitis due to the absence of any organism upon Gram stain or culture of the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), is the most common form of meningitis. Enteroviruses, such as coxsackievirus and echovirus, are the most common causes of viral meningitis. Others include arboviruses herpes simplex, mumps, and HIV. Mumps should be suspected in patients with swollen parotid glands in patients who have not received appropriate vaccination with MMR. In patients at risk, who present with possible symptoms of meningitis, testing for HIV should be done.

Bacterial meningitis in adults is caused primarily by Streptococcus pneumoniae or Neisseria meningitidis. Listeria monocytogenes should be suspected in patients who are pregnant, over 50 years of age or immunocompromised. Mycobacterial meningitis should be suspected in areas where tuberculosis is endemic and in immunocompromised patients such as those with HIV.

Fungal meningitis is usually found in immunocompromised patients. Cryptococcus and Aspergillus species are the most common infecting agents. Candida species also cause meningitis especially in hospitalized patients. In areas where systemic fungal infections are endemic, e.g., coccidioidomycosis in the San Joaquin Valley in California and the Sonoran Desert of Arizona and Northern Mexico should be included in any differential diagnosis of patients suspected to have meningitis.

While presenting symptoms vary in severity and by microorganism, they generally include some combination of headache, fever, neck stiffness (nuchal rigidity), altered mental status, photophobia, nausea/vomiting, seizures, focal neurological deficits, and a skin rash, in addition to generalized fatigue, malaise, arthralgias, and myalgias. The Kernig and Brudzinski signs, once the gold standard for meningeal irritation, have proven to be of limited usefulness (positive predictive level of 27%), because now patients tend to present earlier in the course of the disease. Testing for nuchal rigidity also is only marginally better as a positive predictive sign. Also, the classic triad of fever, neck stiffness, and altered mental status is found in only two-thirds of adults diagnosed with bacterial meningitis. If headache is added as a fourth manifestaion, then 95% of patients with two of the four signs or symptoms were diagnosed with bacterial meningitis.

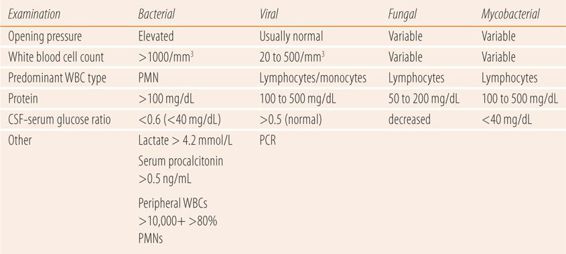

Confirmation of the cause of meningitis depends on examination of the CSF. Table 13.2 provides a guide to the CSF findings in the common forms of meningitis. Generally, CSF pressure, number and type of white blood cells, amount of protein, and glucose levels or ratio of serum to CSF glucose are used. Gram staining the CSF sample will reveal bacteria in 60% to 80% of patients with bacterial meningitis. CSF and blood samples are also sent for culture and susceptibility. Nucleic acid amplification tests such as PCR assays are rapid and are used primarily to detect viral species, mycobacteria, and some fungi and have been used to identify specific bacterial species. Current PCR assays are being more frequently used as costs decline.

| TABLE 13.2 | CSF Differential Diagnosis: Meningitis |

Pseudotumor Cerebri (Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension)

Pseudotumor cerebri is a rare disorder (<1.0/100,000) typically seen in overweight females of childbearing age. It is due to an imbalance between the production and reabsorption of CSF, resulting in increased intracranial pressure and headache. If left unchecked, permanent visual changes can occur. In addition to headache, visual disturbances and papilledema can occur. The reason that it is important to pharmacists is that it can be caused or exacerbated by medications. For example, both minocycline (also other tetracyclines) and isotretinoin have been implicated. Of particular importance is that when filling a new prescription for oral isotretinoin, the pharmacist needs to make sure that the patient stops their minocycline before starting the isotretinoin to reduce the risk of the combination inducing the condition. Women returning for the initial refill should be questioned about new onset headaches and visual problems and the pharmacist should verify that they have stopped any tetracycline.

Acute Trauma/Post-Trauma Headache

A new moderate to severe headache occurring within 12 to 24 hours after closed-head trauma should be referred to urgent/emergent care for evaluation of subarachnoid or intracerebral bleeding. In particular, special attention should be given to patients on drugs that interfere with normal coagulation, e.g., aspirin, clopidogrel, warfarin, regular NSAID use, chronic long-term phenytoin use (due to higher INR due to enzyme induction of vitamin K metabolism).

Post-trauma headaches (post-concussion headaches) can last for weeks after the injury. They can present like all three types of common primary headaches although tension-type headaches are the most common manifestation. Patients with headaches that might be due to a recent history of trauma to the head or neck and shoulders should be referred to the care of a neurologist for evaluation and follow-up.

Cerebrovascular Accident (Stroke)

The role of a pharmacist in the management of patients with diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and oral anticoagulant therapy for patients with atrial fibrillation or prosthetic heart valves is well established in the medical literature. All the above conditions contribute directly or indirectly to a markedly increased risk of stroke (CVA). Therefore, the pharmacist must use their assessment skills at every visit to ascertain whether or not the patient is suffering from this complication of their chronic diseases. In addition, as part of patient education efforts, the pharmacist needs to familiarize the patient with the signs and symptoms of stroke, because successful or optimal prevention of permanent sequelae is dependent on early self-detection and treatment.

Etiology Traditionally, acute cerebrovascular events are divided into two major categories: stroke or CVA and transient ischemic attack (TIA). Previously, a TIA was characterized as a cerebrovascular event without infarction, leading to focal neurological signs and symptoms that lasted less than 24 hours and left no residual effects. TIAs have also been called reversible ischemic neurological deficit (RIND), which is consistent with the older definition. A stroke or CVA was defined as focal neurological signs and symptoms that lasted greater than 24 hours and involved infarction of brain tissue. Recent evidence has shown that this classic 24-hour distinction is misleading in that many patients with transient (<24 hours) symptoms actually have a cerebral infarction. A task force of the American Heart Association has recommended that the 24-hour distinction between TIA and CVA should be removed based on a review of the literature. Instead the differentiation of CVA and TIA should be defined in terms of tissue damage (infarction). The task force recommended that the definition of TIA be changed to a transient neurological dysfunction caused by focal brain, spinal cord, or retinal ischemia, without acute infarction. No time frame was attached to transient. The definition of stroke was changed to an infarction of central nervous system tissue. Further, they recommended that analogous to acute coronary syndrome the spectrum of neurovascular events affecting the brain be called acute neurovascular syndrome. Therefore, past comparisons of TIA to angina pectoris and CVA to myocardial infarction are no longer considered correct or applicable. However, they did not go so far as to define the elements of the spectrum as has been done with chest pain (STEMI versus NSTEMI versus unstable angina). We have known that these multiple silent infarctions or ministrokes, (up until now classified as TIAs) have been implicated as the etiology of the largest group of patients with dementia, i.e., multi-infarct dementia. In addition, evidence shows as many as 20% to 25% of high-risk patients with a TIA will have a stroke within the next 90 days, most likely during the week after the TIA. Therefore, any signs or symptoms potentially indicative of any acute cerebrovascular event require immediate referral for a comprehensive workup and definitive care.

Acute cerebrovascular events have two major causes: ischemic and hemorrhagic. Ischemic events (80% to 88%) are primarily due to atherosclerosis or embolism. The atherosclerotic process is the same as for myocardial infarction, and is associated with a gradual accumulation of intra-arterial plaque. If the plaque is unstable, it may eventually rupture initiating a platelet-based clot, which may progress to decreased circulation and a subsequent infarct. Embolic strokes are due to clots that form in the heart in patients with atrial fibrillation or prosthetic cardiac devices such as a heart valve. A portion of the clot becomes dislodged and ultimately travels to a part of the circulatory system of the brain, which is too narrow for it to pass through. The result is obstruction of the circulation to tissue past that point. Hemorrhagic strokes (12% to 15%) are due to a ruptured aneurysm or blood vessel. Uncontrolled hypertension and a combination of hypertension and atherosclerosis are the primary etiologies in hemorrhagic strokes.

Diagnosis While this evidence-based change in definition does not impact the pharmacist’s role in the early detection of symptoms or control of predisposing conditions such as dyslipidemia, hypertension, and diabetes, it does change the urgency with which patients with those symptoms need to be referred. It also increases the importance of patient education in self-recognition of potential acute neurovascular syndrome symptoms and the need for immediately seeking care when they occur.

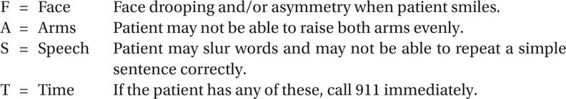

Manifestations of acute neurovascular syndrome include impaired speech or language, visual disturbances, double vision or visual loss, facial drooping, trouble swallowing, weakness or numbness/tingling on one side of the body, impaired coordination of limbs or gait dysfunction, vertigo, dizziness, stiff neck, headache, sudden change in behavior (often recognized by people other than the patient), seizure, syncope, confusion, or cognitive impairment. One simple aid that may help in teaching patient self-recognition skills of the more apparent signs and symptoms of stroke is the mnemonic FAST.

Specific physical findings to confirm the dysfunction could include dysarthria (trouble speaking), cranial nerve deficits, unilateral weakness, unilateral loss of sensation, cerebellar dysfunction, and abnormal pupil examination. The dysfunction may be of short duration if it is a small infarction or it may continue in the case of a larger infarction.

A diffusion weighted imaging MRI (MRI-DWI) is the test of choice due to its sensitivity to detect small infarctions and distinguish between new and old lesions, and even between ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke. The MRI should be done as soon as possible, at least within 24 hours even if the dysfunction lasts less than 2 hours. Trans-cranial and carotid Doppler ultrasonography, CT or MR angiography, or CT scan are alternative imaging tests if MRI-DWI is not readily available.

Roughly one-third of patients referred for a stroke workup do not have a stroke. Alternative diagnoses may include seizures, sepsis, encephalopathy, mass occupying lesion, syncope, delirium, dementia, migraine, subdural hematoma, hypo- or hyperglycemia, benign paroxysmal positional vertigo, psychogenic/functional cases, and cervical or lumbar spine disorders. Many of these causes can be established (thereby ruling out stroke) by history, physical examination, routine laboratory tests, and brain imaging.

• SUMMARY

The pharmacist’s role in preventing acute cerebrovascular events focuses on the control of comorbid conditions such as hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, and anticoagulation that can lead to TIA and/or stroke. In addition, pharmacists can play a major role in educating patients with those disorders to readily recognize signs and symptoms of acute neurovascular syndrome and if present to seek immediate help. At every visit for these comorbid disorders, the pharmacist needs to probe for typical symptoms and via neurological examination probe for typical signs. By doing this at every visit, it reinforces the patient’s understanding of self-recognition.

• KEY REFERENCES

1. Crystal SC, Robbins MS. Epidemiology of tension-type headaches. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2010;14:449-454.

2. Bendtsen L, Jensen R. Tension type headaches. Neurol Clin. 2009;27:525-535.

3. Bartleson JD, Cutrer M. Migraine update: diagnosis and treatment. Minn Med. 2010;93:36-41.

4. Van Kleef M, Lataster A, Narouze S, Mekhail N, Geurts JW, van Zundert J. Cluster headache. Pain Pract. 2009;9:435-442.

5. Martin VT. The diagnostic evaluation of secondary headache disorders. Headache. 2011;51:346-352.

6. Clinch CR. Evaluation of acute headaches in adults. Am Fam Physician. 2001;63:685-691.

7. Goncalves DAG, Camaris CM, Speciali JG, et al. Tempomandibular disorders are differentially associated with headache diagnosis: a controlled study. Clin J Pain. 2011;27:611-615.

8. Evers S, Marziniak M. Clinical features, pathophysiology and treatment of medication-overuse headaches. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9:392-401.

9. Chadwick DR. Viral meningitis. Br Med Bull. 2006;75-76:1-14.

10. Lin AL, Safdieh JE. The evaluation and management of bacterial meningitis: current practice and emerging developments. Neurologist. 2010;16:143-151.

11. McArthur KS, Quinn TJ, Walters MR. Diagnosis and management of transient ischaemic attack and ischemic stroke in the acute phase. BMJ. 2011;342:1938.

12. Cucchiara B, Kasner SE. In the clinic: transient ischemic attack. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154(1):ITC11-15.

13. Easton JD, Saver JL, Albers GW, et al. Definition and evaluation of a transient ischemia attack. Stroke. 2009;40:2276-2293.

14. Rhoney DH. Contemporary management of transient ischemic attack: role of the pharmacist. Pharmacotherapy. 2011;31(2):193-213.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree