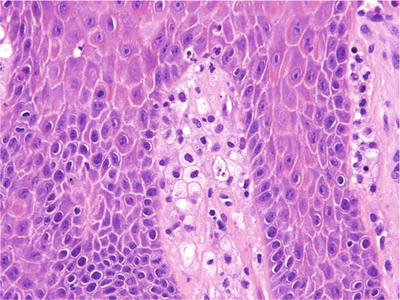

Fig. 24.1.

Multinucleate cells with ground glass nuclear change characterize infection with Herpes simplex virus.

Oral Hairy Leukoplakia

Clinical

♦

This condition represents a peculiar manifestation of Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) infection , mostly in immunosuppressed hosts. Usually, bilateral linear striations are seen on the lateral border of tongue. Oral hairy leukoplakia may be seen in AIDS, organ transplant patients, diabetics, and cancer patients. On rare occasions, this infection can be seen in immunocompetent hosts

Microscopic

♦

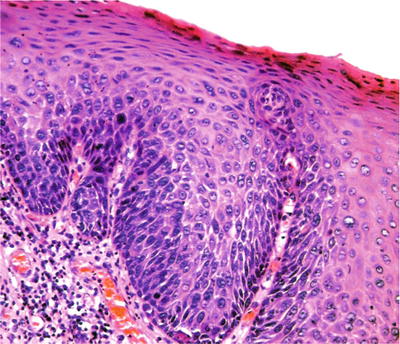

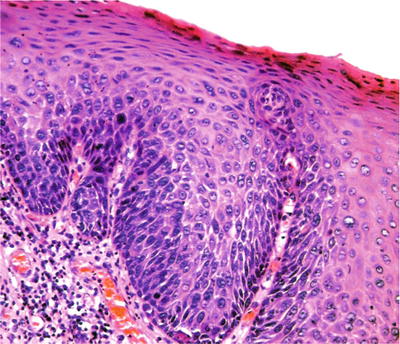

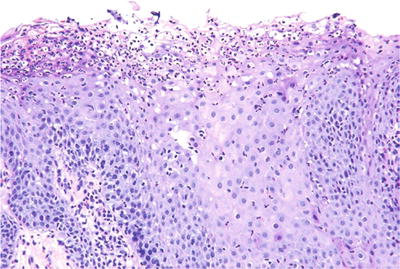

Upon microscopic examination, hyperkeratosis is seen beneath which is a linear band of cells with pale cytoplasm and nuclei that demonstrate chromatin margination (Fig. 24.2A, B). In situ hybridization will illuminate EBV within these cells. Superimposed candidiasis is present in most cases

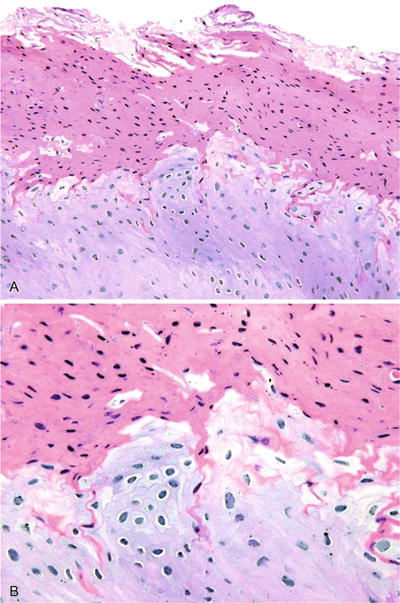

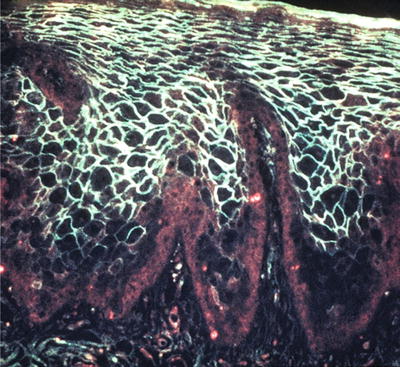

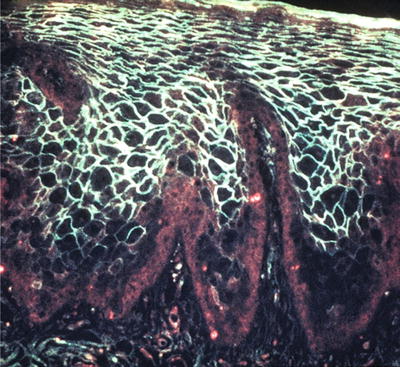

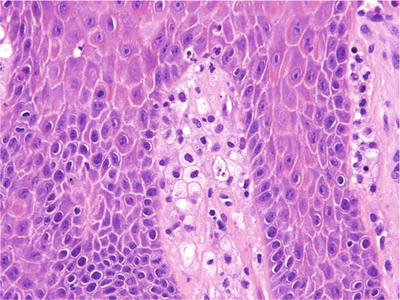

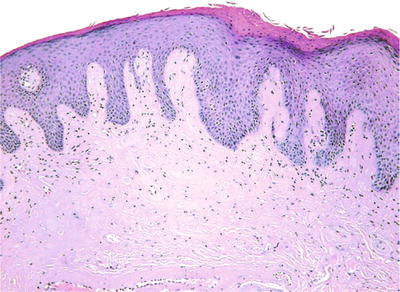

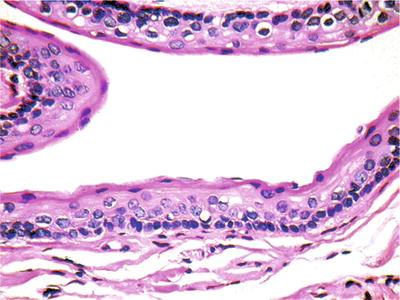

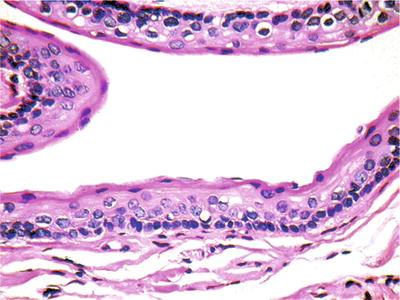

Fig. 24.2.

The hyperkeratotic lesions of oral hairy leukoplakia usually present on the lateral border of the tongue in immunosuppressed patients (A). Cellular changes characterized by edematous cytoplasm and nuclei that demonstrate chromatin margination are secondary to Epstein–Barr virus (B).

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Morsicatio linguarum (tongue chewing)

This condition demonstrates thickened parakeratin with a ragged surface and adherent bacterial colonies but lacks candidal infection and EBV

Human Papillomavirus

Clinical

♦

Human papillomavirus infection will produce typically non-cancerous papillary lesions of the oral cavity – papillomas, condylomas, and verrucae. Commonly, these are seen in young patients on tongue, gingiva, and soft palate complex. These possess a papillary growth pattern and are generally small, localized lesions

Microscopic

♦

The squamous papilloma demonstrates a papillary epithelial proliferation arising from a stalk or pedunculated base. Verrucae demonstrate coarse keratohyaline granules, hyperkeratosis, and axial inclination of rete ridges. Condylomas demonstrate koilocytes and broader papillations and branching. The presence of condylomas in children may suggest child abuse. Although not thought to be a significant risk factor for carcinomas of the oral cavity proper, HPV types 16 and 18 are highly associated with squamous cell carcinomas of tonsil/oropharynx

Disseminated Fungal Infection

Clinical

♦

A variety of disseminated fungal infections may have oral manifestations, including histoplasmosis, blastomycosis, cryptococcosis, and coccidioidomycosis. Most, but not all, patients demonstrate a definable immunodeficient state (i.e., HIV, diabetes, status post-organ transplantation, malignancy). These infections are accompanied by oral ulceration, weight loss, and fevers. In many instances, oral lesions are preceded by pulmonary infection

Microscopic

♦

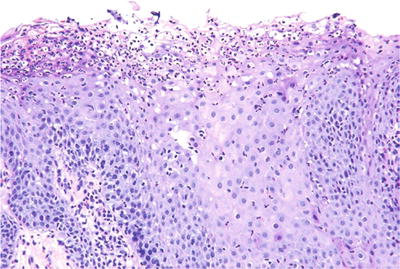

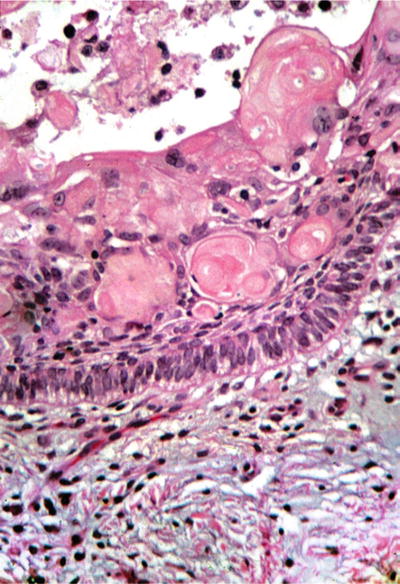

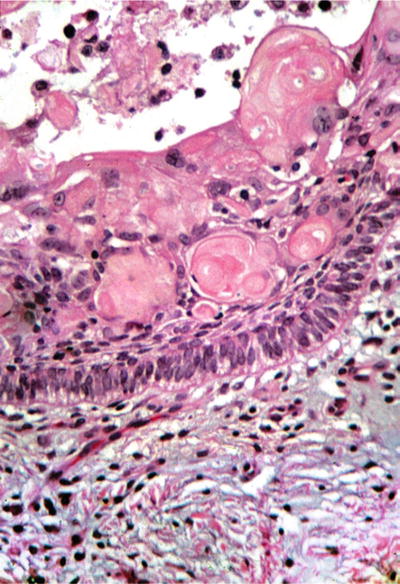

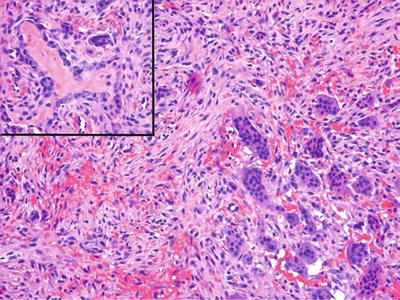

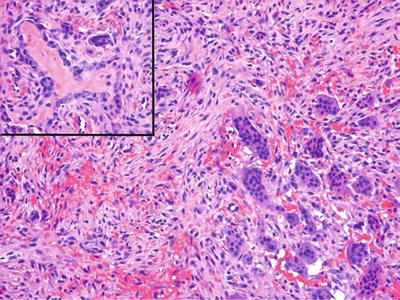

Typically granulomatous inflammation is seen, including histiocytes, giant cells, and necrosis (Fig. 24.3). The presence of a neutophilic infiltration with giant cells is characteristic of blastomycosis. Blastomycosis is notorious for associated pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, simulating squamous cell carcinoma. Discrete granulomas may be absent in histoplasmosis (i.e., organism-laden, foamy histiocytes with necrosis and nonspecific inflammation). Fungal stains (GMS and PAS) may aid identification of microorganisms

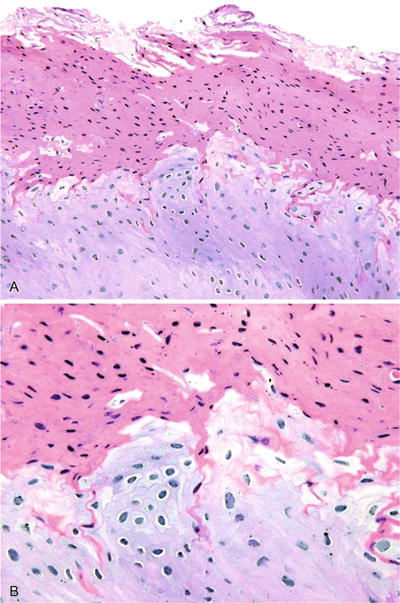

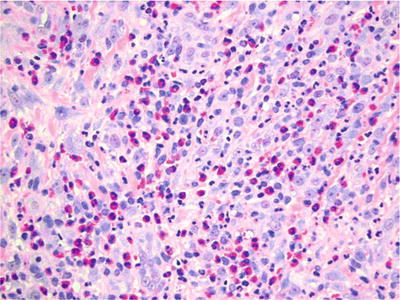

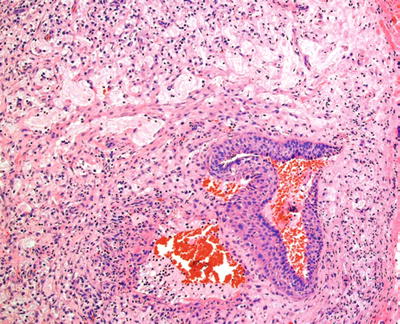

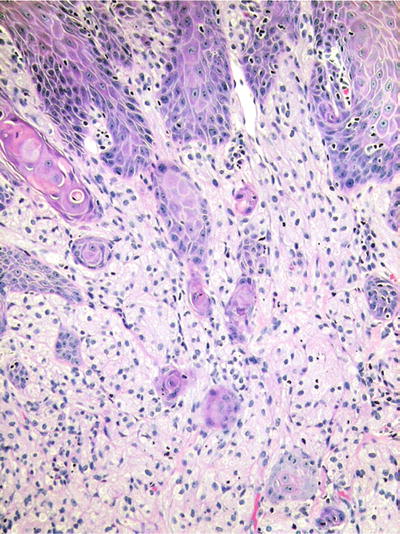

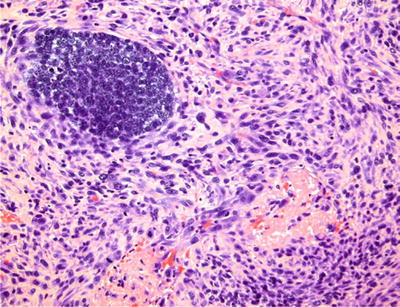

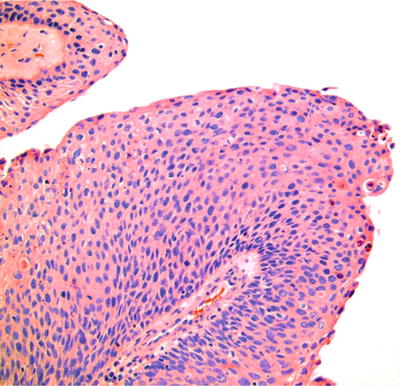

Fig. 24.3.

Oral manifestations of histoplasmosis often reflect disseminated disease . Inset: GMS stain highlights yeast.

Immune-Mediated Disease

Lichen Planus

Clinical

♦

This mucocutaneous disease is characterize d by bilateral, symmetrical white striations (striae of Wickham) superimposed upon an erythematous background. Most commonly this is seen in perimenopausal females on the buccal mucosa, tongue, or gingiva. In the erosive form, it presents as an erythematous lesion with faint peripheral striations

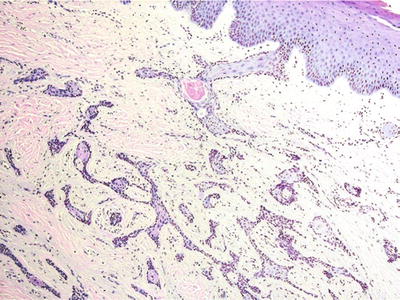

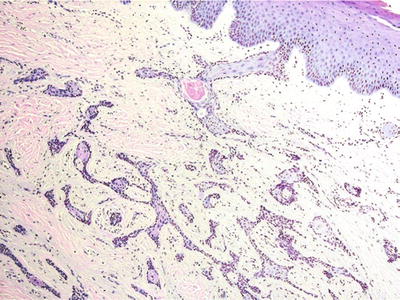

Microscopic

♦

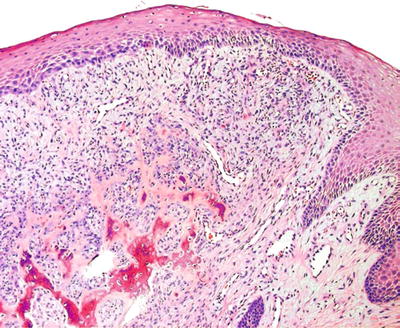

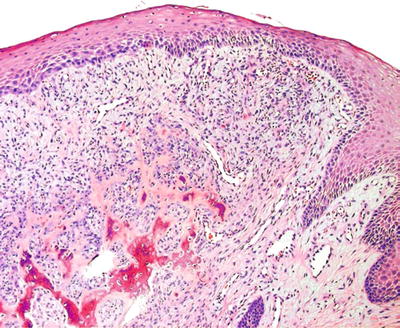

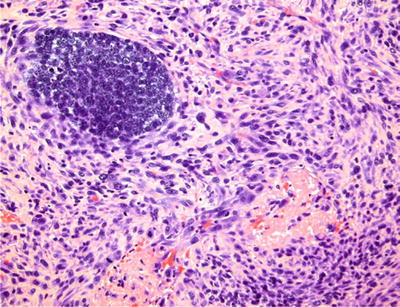

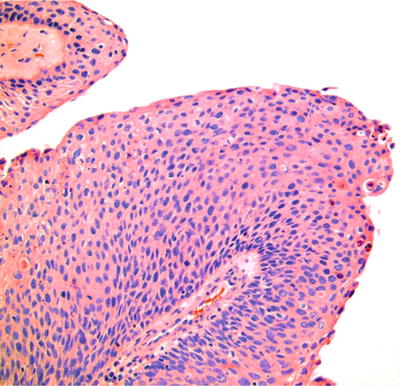

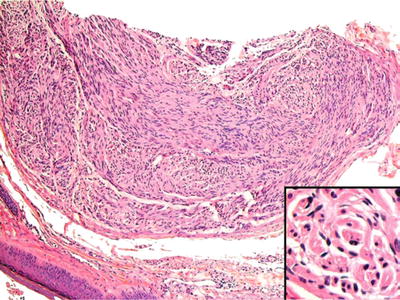

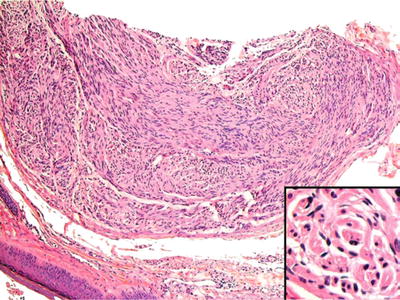

A band-like infiltrate of lymphocytes obscuring the epithelial/connective tissue junction represents the seminal microscopic feature (Fig. 24.4). Spike-shaped rete ridges and dissolution of basal epithelial layer are also apparent

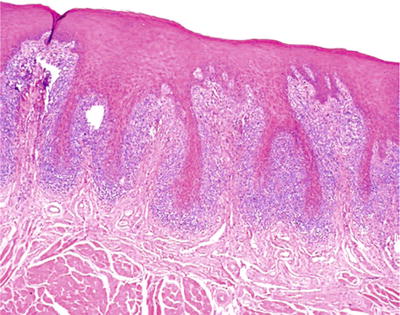

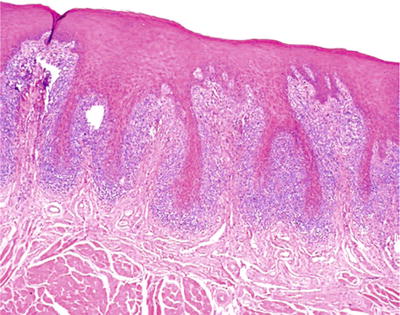

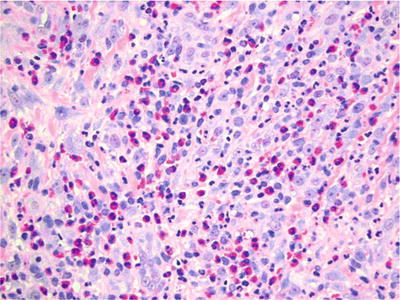

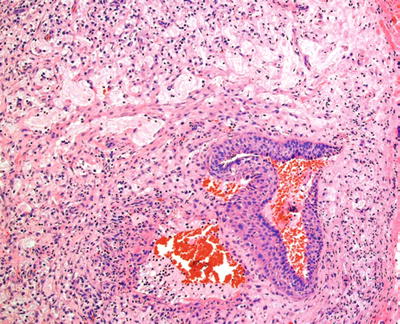

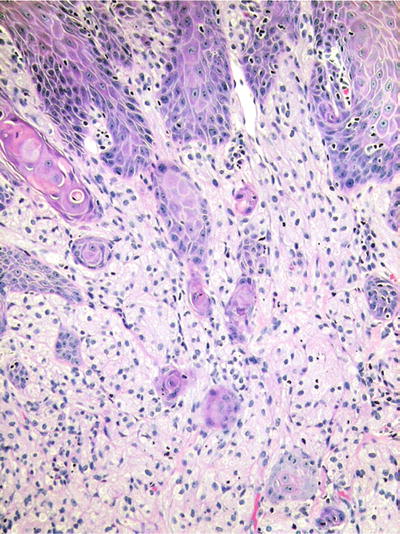

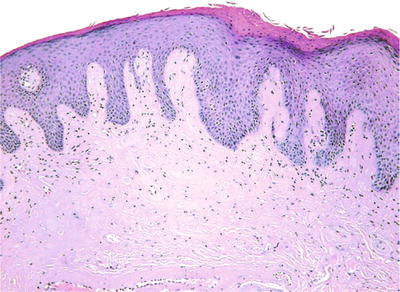

Fig. 24.4.

Band-like inflammatory infiltrates and spike-shaped rete ridges characterize lichen planus .

Immunofluorescence

♦

Should direct immunofluorescent testing be undertaken, granular deposition of fibrinogen is observed at the basement membrane level

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Lichenoid mucositis

Histologically this is similar to lichen planus but typically is not symmetrical. This may be due to a variety of stimuli – dental products, dental materials, and systemic medication

♦

Epithelial dysplasia with lichenoid inflammation

Epithelial alterations consistent with irreversible, precancerous change probably account for most cases of “malignant transformation” of lichen planus

Benign Mucous Membrane (Cicatricial) Pemphigoid

Clinical

♦

This immunologically mediated disease demonstrates generalized sloughing of epithelium leaving a bleeding erythematous base. The typical population is peri-/postmenopausal females. Often sloughing can be elicited with gauze or a gloved finger. Ocular and genital mucosal involvement may also be seen

Microscopic

♦

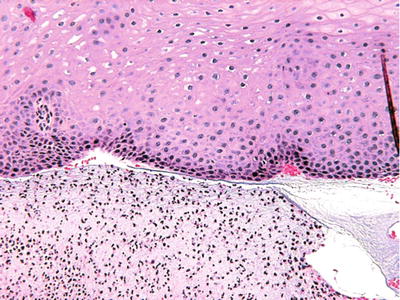

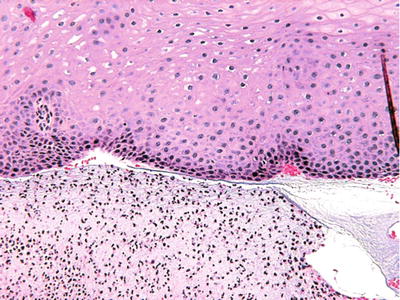

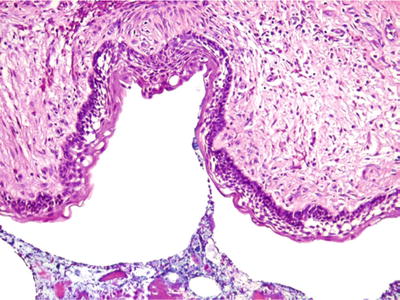

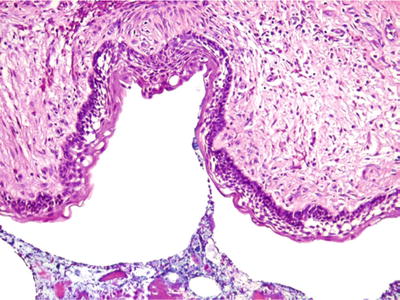

Subbasilar separation of the epithelium is characteristic of this condition (Fig. 24.5). A diffuse chronic inflammatory infiltrate of lymphocytes is seen with a smattering of neutrophils

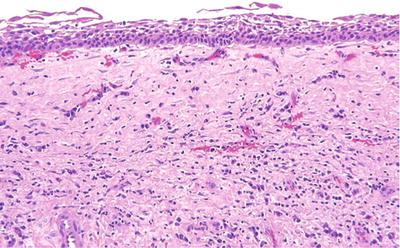

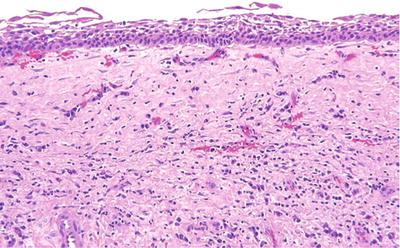

Fig. 24.5.

Subbasilar separation of the epithelium with chronic inflammation.

Immunofluorescence

♦

Linear deposition of C3 and IgG along the basement membrane zone is seen in almost all cases in which direct immunofluorescence is performed

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Lichen planus

Can demonstrate separation but basal layer is lost. The lymphocytic infiltrate is typically more band-like

♦

Pemphigus vulgaris

Separation occurs above the basal layer, and Tzanck cells may be present

Pemphigus Vulgaris

Clinical

♦

Widespread sloughing and ulceration of mucosa are the typical manifestations. Young adult males and females are the commonly afflicted individuals. This can manifest primarily as gingival desquamation without cutaneous lesions

Microscopic

♦

Suprabasilar separation of the epithelium is seen, possibly with evidence of Tzanck cells. The inflammatory infiltrate is composed mostly of lymphocytes

Immunofluorescence

♦

Intraepithelial (desmosomal) deposition of C3 and IgG in a spider web pattern is characteristic of pemphigus when viewed with immunofluorescence (Fig. 24.6)

Fig. 24.6.

Direct immunofluorescence revealing IgG positivity in the desmosomal areas.

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Lichen planus, see above

♦

Cicatricial pemphigoid, see above

♦

Drug-induced pemphigus

Can be seen in particular with penicillamine

♦

Paraneoplastic pemphigus

Supra- and subbasilar splits are seen in patients with lymphoma and leukemia

Inflammatory/Nonneoplastic Lesions

Peripheral Ossifying Fibroma

Clinical

♦

This represents a reactive mesenchymal proliferation of periodontal ligament origin that retains the capacity to form bone or cementum-like product. Most commonly seen in the second to third decade, the peripheral ossifying fibroma demonstrates a female predilection. Occurring exclusively on the gingiva, it presents as a broad-based nodule that is typically ulcerated and asymptomatic

Microscopic

♦

The microscopic features include a cellular mesenchymal tissue with intermixed calcifications that can resemble bone or cementum (Fig. 24.7). It often extends to the base because of its origin in the periodontal ligament, resulting in recurrence

Fig. 24.7.

Peripheral ossifying fibroma is a gingival-based nodule exhibiting matrix (i.e., bone or cementum) production.

Peripheral Giant Cell Granuloma

Clinical

♦

Considered a reactive proliferation of vascular mesenchymal tissue with intermixed osteoclasts, the peripheral giant cell granuloma has a propensity to occur in older adults in the fourth to sixth decades. It appears as a lobular, blue to purple mass on the gingiva/alveolar ridge. It may erode bone superficially, resulting in an alveolar radiolucency

Microscopic

♦

The peripheral giant cell granuloma consists of an exuberant mass of spindle-shaped cells with numerous extravasated erythrocytes, hemosiderin pigment (especially at the periphery), and multinucleated giant cells. Because of its location, it can recur with frequency

Verruciform Xanthoma

Clinical

♦

This interesting entity represents a peculiar reactive proliferation of lipid-laden macrophages with a papillary surface configuration. Typically occurring on the gingiva or palatal mucosa in adults, it can appear red to yellow in coloration with a granular surface that may look like a volcano crater

Microscopic

♦

The histologic appearance is that of papillary proliferations of epithelium with brightly eosinophilic keratin beneath which the connective tissue papillae are filled with lipid-laden macrophages (Fig. 24.8). These cells will be confined to papillary lamina propria

Fig. 24.8.

The connective tissue papillae are filled with lipid-laden macrophages in verruciform xanthoma.

Traumatic Ulcerative Granuloma With Stromal Eosinophilia

Clinical

♦

This peculiar exuberant reactive process can mimic squamous cell carcinoma in its clinical presentation. Typically present on the dorsolateral tongue in adults, it manifests as an exophytic ulcerative mass usually of several weeks duration. This may be painful and persist even after multiple surgeries

Microscopic

♦

Surface ulceration is seen overlying a proliferation of inflamed granulation tissue with prominent, reactive endothelial cells (Fig. 24.9). Eosinophils and macrophages are prominent in the deeper aspects approximating and involving muscle

Fig. 24.9.

The ulcer bed in traumatic ulcerative granuloma with stromal eosinophilia can be extremely cellular and mistaken for a neoplastic process.

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Squamous cell carcinoma but only from a clinical perspective

♦

Lymphoma

Atypical lymphoid cells, clonal

Aside from NK/T-cell lymphomas , which may be polymorphous , most lymphomas are monomorphic infiltrates, contrasted to mixed infiltrate of traumatic ulcerative granuloma. Lymphoma will generally lack prominent eosinophils

Mucous Extravasation Phenomenon (Mucocele/Ranula)

Clinical

♦

This is a reactive lesion representing spillage of mucin into tissue due to duct damage. Typically young patients, first to second decade, represent the common population. Mucoceles occur most commonly in the lower lip, ranulae in the floor of mouth. The clinical appearance is that of a dome-shaped, fluid-filled lesion that may wax and wane with rupture. A “plunging ranula” presents as a central neck mass and may simulate thyroglossal duct cyst

Microscopic

♦

Pseudocystic accumulations of mucin surrounded by macrophages, a wall of compressed granulation tissue, and inflammation represent the salient diagnostic features (Fig. 24.10)

Fig. 24.10.

Disruption of salivary gland ducts results in mucin extravasation into connective tissue.

Necrotizing Sialometaplasia

Clinical

♦

An ulcerative lesion involving salivary gland, necrotizing sialometaplasia can mimic malignancy . Although its etiology is unclear, it is possibly due to underlying ischemic event. Younger adults are most commonly affected, with the palate representing the most common site. Swelling with pain followed by a sharply demarcated ulceration over a 2-week period represents the typical clinical progression

Microscopic

♦

Necrotizing sialometaplasia is characterized by coagulative necrosis of acinar units with surface ulceration and squamous metaplasia of salivary ducts. However, there is maintenance of lobular architecture of salivary gland. Because of the squamous metaplasia, it can mimic squamous cell carcinoma or mucoepidermoid carcinoma

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Squamous cell carcinoma

Infiltrative growth, cytologic atypia, nonlobular growth pattern, and surface epithelial features

♦

Mucoepidermoid carcinoma

Infiltrative growth , prominent appearance of mucous cells, no necrosis of acinar units

Benign Neoplasms

Granular Cell Tumor

Clinical

♦

This is a benign , nonneoplastic proliferation of probable perineural sheath cells. Seventy percent occur on the tongue, primarily dorsum, as a deep mass with maintenance of surface architecture. These often represent long-standing processes

Microscopic

♦

Ill-defined collections of cells with granular cytoplasm, eccentric nuclei, and indistinct cytoplasmic boundaries constitute the primary histologic features (Fig. 24.11). Many cases have superimposed pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, mimicking squamous cell carcinoma. Granular cell tumors tend not to recur, even with incomplete removal

Fig. 24.11.

Granular cell tumors are notorious for inducing pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia of the overlying epithelium.

Immunohistochemistry

♦

S100 protein+

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Squamous cell carcinoma

Lacks the subepithelial granular cells that accompany pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia. Rare on the dorsum of the tongue where granular cell tumor is common

Congenital Gingival Granular Cell Tumor (Congenital Epulis)

Clinical

♦

The congenital gingival granular cell tumor is a benign proliferation of granular cells on the alveolar ridge in newborns. This manifests as an exophytic mass, often large (greater than 5 cm), on the maxillary alveolar ridge most commonly. As the name implies, it is typically present at birth

Microscopic

♦

This appears as a mass of cells with granular cytoplasm, often demonstrating distinct cell boundaries. The overlying epithelium is typically atrophic

Immunohistochemistry

♦

S100−

Premalignant/Malignant Neoplasms

“Leukoplakia”

♦

This represents strictly a clinical term and should never be used as a microscopic diagnosis. All it confers is a white patch and, as such, carries no histologic implications. The clinical location, symptoms, and risk factors are far more important in assessing the risk of preneoplasia/carcinoma. The microscopic diagnosis ranges from hyperkeratosis to squamous cell carcinoma. It is recommended that the use of the term be discouraged

Epithelial Dysplasia/Carcinoma In Situ

Clinical

♦

As with other sites , the oral epithelium tends to demonstrate precursor lesions prior to frank invasion. Most classifications grade epithelial dysplasia to carcinoma in situ dependent upon the degree and thickness of epithelial involvement. This may present as a white patch, red patch (erythroplakia), or ulcer. Typically epithelial dysplasia/carcinoma in situ is seen in patients over 40 who are also smokers and drinkers. Females now represent approximately 50% of cases. Ventrolateral tongue, floor of mouth, and soft palate complex represent high-risk sites for these squamous cell carcinoma precursors

Microscopic

♦

The histologic features include nuclear enlargement, hyperchromatism, pleomorphism, loss of polarity, and architectural changes (i.e., formation of bulbous rete ridges ) (Fig. 24.12)

Fig. 24.12.

The most apparent atypical changes of severely dysplastic epithelium in the oral cavity may be limited to lower aspect of the epithelium.

♦

WHO classification of oral dysplasia:

Mild – lower one-third abnormalities

Moderate – lower one-half abnormalities

Severe – lower two-thirds abnormalities

Carcinoma in situ – full-thickness abnormalities

♦

The grade of dysplasia does correlate with risk of squamous cell carcinoma (i.e., the higher the grade, the greater the risk). It is generally considered that moderate dysplasia and higher represents high-grade dysplasia and should be reported as such. Reproducibility of grading oral dysplasia (both intra- and interobserver) is generally poor

Proliferative Verrucous Leukoplakia

Clinical

♦

Proliferative verrucous leukoplakia represents a relatively recently described progressive condition involving multiple sites in the oral cavity. It occurs in the fifth decade or later and has a female predilection. No strong tobacco association is apparent. Multiple white patches are seen that tend to enlarge, become verrucous, and coalesce over time. It usually progresses to squamous cell carcinoma in less than a decade. It has yet to be successfully managed with consistency by any means

Microscopic

♦

Within a given patient, it can vary from site to site in the oral cavity from verrucous hyperkeratosis to epithelial dysplasia to verrucous carcinoma to squamous cell carcinoma

Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Clinical

♦

This represents the most common malignancy in the oral cavity. Ventrolateral tongue, floor of mouth, and gingiva are the common sites of origin. Mostly seen in smokers and/or drinkers over age of 40, some studies suggest an increasing element of cases in younger patients without known risk factors. Although often suspected, HPV has yet to be shown to play a major role in oral cavity proper carcinomas. Once predominantly a male disease, females are increasing in incidence to 50% of cases. It manifests as white patch, red patch, ulcer, or exophytic mass

Microscopic

♦

Characteristically , invasive and proliferative squamous epithelium is seen demonstrating the cytologic and morphologic alterations seen in epithelial dysplasia, with the addition of keratin pearls. The level of differentiation is graded as well, moderately, or poorly differentiated. Histologic grade does correlate with disease aggressiveness, although not as directly as clinical stage. Depth of invasion (>4 mm) and perineural invasion represent negative predictors. Currently, ~50% of patients survive 5 years, relatively unchanged over the last half century

Differential Diagnosis

♦

See Table 24.1

Table 24.1.

Differential Diagnosis of Poorly/Undifferentiated Neoplasms

Considerations | Immunohistochemistry/molecular findings | |

|---|---|---|

Squamous cell carcinoma | Squamous differentiation: keratin, intercellular bridges, and/or dyskeratotic cells | AE1/AE3+, 34βE12+, CK5/6+, p63+, p40+ |

Basaloid squamous cell carcinoma | Undifferentiated basaloid cells | AE1/AE3+, 34βE12+, CK5/6, p63 diffusely +, p40+, p16+/−, HPV+/− (infreq), synaptophysin–, chromogranin– |

Squamous differentiation, “mosaic pattern” of keratinization | ||

Lymphoma | CD45/LCA+ | |

Various lymphoid markers + depending on cell lineage | ||

Cytokeratins− | ||

Nasal type, NK/T type: EBV (EBER+) | ||

Adenoid cystic carcinoma, solid type | Peripheral myoepithelial cells present | AE1/AE3+, CK7+, CK5/6+, CAM5.2+ |

Peripheral myoepithelial cells + for p63, SMA, calponin, S100 | ||

p16+/−, HPV+/− (infreq) | ||

MYB protein+ (80%) | ||

Sinonasal undifferentiated carcinoma | No squamous or glandular differentiation | AE1/AE3+, p16+ (HPV–) |

CK5/6−, p63−, p40− | ||

CD99 infreq | ||

Synaptophysin, chromogranin infreq | ||

EBV− | ||

Sinonasal melanoma | Diverse histology, prominent nucleoli, cytoplasmic nuclear inclusions | S100+, HMB45+, tyrosinase+, Melan-A+, MiTF+ |

FLi-1+, CD99−/+ | ||

Small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma | AE1/AE3+ (dot), CAM5.2+ (dot) | |

Synatophysin+/−, chromogranin+/− | ||

TTF1+/−, CD56+/− | ||

CK5/6, 34βE12, p63, FLi-1 infreq | ||

Lymphoepithelial carcinoma | EBV+ tumors are radiosensitive | AE1/AE3+, CD5/6, 34βE12+, p63+, EBV (EBER+) |

Histologically indistinguishable from nasopharyngeal carcinoma | S100− | |

Olfactory neuroblastoma | Upper nasal cavity and cribriform plate tumors | Synaptophysin+, chromogranin+, CD56+, calretinin+ |

Homer Wright and Flexner–Wintersteiner rosettes may be present | S100+ sustentacular cells | |

AE1/AE3+ and CAM5.2+ in up to 30% of cases | ||

Rhabdomyosarcoma | Arise in children or adults | Desmin+, actins+, myoglobin+, myosin+, myogenin+, MiTF+, MyoD1+ |

AE1/AE3, CAM5.2, and synaptophysin may be weakly positive | ||

Ewing sarcoma/PNET | Most arise in children, adolescents | CD99+, FLi-1+ |

Cytoplasm glycogen may be abundant | t(11;22)(q24;q12): EWSR1/FLi-1 fusion (90%) | |

t(21;22)(q22;q12): EWSR1/ERG fusion (5–10%) positivity for AE1/AE3 and/or CAM5.2 can be seen | ||

NUT midline carcinoma | Undifferentiated cells with or without abrupt keratinization | AE1/AE3+, p63+, NUTM1+ |

Children or adults affected | ||

Mesenchymal chondrosarcoma | Cartilage rules out Ewing sarcoma | S100+ (cartilaginous component) |

CD99+ | ||

Cytokeratins−, melanoma markers- | ||

Ewing family t(11:22) absent | ||

Pituitary adenoma | May invade from CNS or arise ectopically | AE1/AE3+(dot), CAM5.2+/−(dot), synaptophysin+, CD56+, chromogranin+, CD99+/– |

Lacks mitoses | 80%+ for a pituitary hormone (prolactin, FSH, LH ACTH, TSH GH) |

Verrucous Carcinoma

Clinical

♦

This represents a low-grade, well-differentiated variant of squamous cell carcinoma. Usually seen over the age of 60, it is more commonly seen in smokeless tobacco users than smokers. Characterized by a large (>4 cm) papillary mass with a broad base, verrucous carcinoma is often snow white due to hyperkeratosis. Generally, it is seen on tongue, alveolar mucosa, and buccal mucosa and is often of long-standing duration. As it is usually nonmetastazing, neck dissection is not indicated

Microscopic

♦

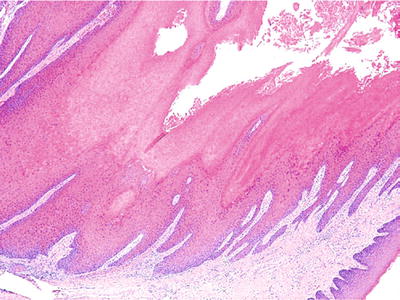

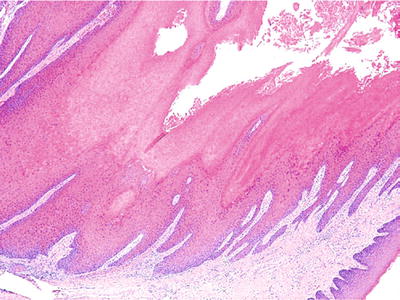

Verrucous carcinoma varies from standard squamous cell carcinoma by exhibiting broad papillations of squamous epithelium exhibiting minimal atypia with deeply invaginated folds of parakeratin (“parakeratin plugging”) (Fig. 24.13). If cytologic atypia is present, the diagnosis of “verrucous”-type carcinoma should be doubted as it probably represents a papillary keratinizing well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma. This malignancy has an excellent prognosis with a 95% 5-year survival rate

Fig. 24.13.

Verrucous carcinoma is a broad-based, hyperkeratotic tumor that infiltrates in a “pushing” fashion.

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Papillomas

Typically smaller, well-confined lesions with a pedunculated base

Sarcomatoid (Spindle Cell) Carcinoma

Clinical

♦

This represents a poorly differentiated variant of squamous cell carcinoma. Usually, sarcomatoid carcinoma manifests after age of 40 and can occur in a history of radiation or burns, particularly electrical. Usually, it occurs as a polypoid, ulcerated mass on posterior tongue or in oropharynx

Microscopic

♦

The microscopic appearance is that of an exuberant proliferation of anaplastic spindle-shaped cells that appear to “drop off” from atypical surface epithelium (Fig. 24.14)

Fig. 24.14.

Spindle cell carcinoma , surrounding a focus of malignant basaloid cells, simulates sarcoma.

Immunohistochemistry

♦

Cytokeratin 5/6+, vimentin+, p63+

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Spindle cell sarcomas

Cytokeratin−

Most superficial spindle cell malignancies in the oral cavity are carcinomas

Nonkeratinizing Papillary Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Clinical

♦

A relatively recent addition to the literature , this represents an exophytic variant of squamous cell carcinoma that is highly associated with HPV types 16 and 18. There is a predilection for oropharynx (tonsil, base of tongue) and hypopharynx. The prognosis is generally more favorable and probably relates to depth of stromal invasion more than size of exophytic component

Microscopic

♦

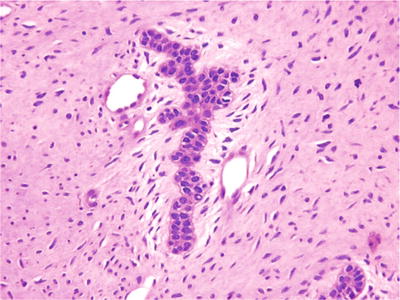

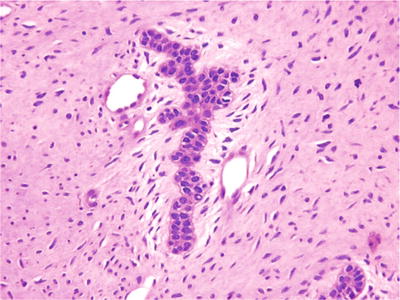

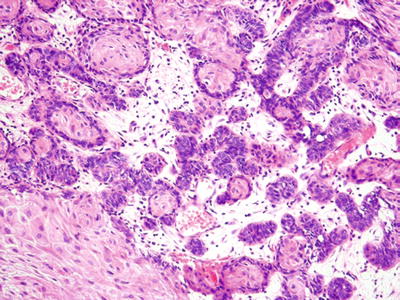

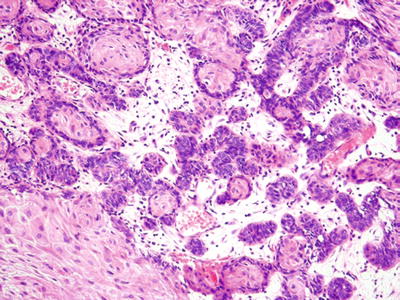

A branching papillary architecture is seen (Fig. 24.15). Brisk mitotic activity and notable cytologic atypia are commonly present with limited to no keratin production

Fig. 24.15.

Papillary squamous cell carcinoma has a predilection for the oropharynx, including the tonsil, and is associated with human papillomavirus.

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Squamous papilloma

Lacks the cytologic atypia and architectural complexity of papillary squamous cell carcinomas

Malignant Melanoma

Clinical

♦

This is a rare malignancy arising from mucosal melanocytes. Typically, it is seen in adults throughout the mucosa, although more commonly in the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses. It may present as a lesion of long-standing duration with widespread discoloration. In addition, it also can occur as an exophytic pigmented mass

Microscopic

♦

The cells are typically large with prominent red nucleoli and abundant cytoplasm. Although often amelanotic, some dusky pigment can be seen with diligent searching. It is imperative to determine whether the lesion is primary or metastatic. It is useful to identify atypical cells within the mucosal epithelium. Mucosal melanoma has a poor prognosis due to its aggressive nature and delay in diagnosis

Miscellaneous Lesions

Adenomatoid Hyperplasia

♦

This represents enlarged mucous glands in a tumor-like pattern seen in the palate. It may actually represent normal glands overlying a neoplasm and thus should be investigated thoroughly

Amalgam Tattoo

♦

The amalgam tattoo is a localized discolored area demonstrating granular, black foreign material aligned along collagen fibers and staining basement membrane. It is typically seen in area of dental restorations

Aphthous Stomatitis

♦

These are ulcerations seen primarily in the lining non-keratinized mucosa in a variety of patterns. Minor aphthae are less than 1 cm ulcers with a fibrinous membrane and halo of erythema. Herpetiform aphthae consist of multiple punctate erythematous ulcerations. Major aphthae are large, greater than 2 cm, ulcerations with significant pain. No distinctive histopathology is seen with these lesions, rather they are clinical diagnoses

Dermoid Cyst

♦

This developmental anomaly is seen in the midline floor of the mouth and exhibits a keratinized lining with adnexal structures. True teratomas are rarely seen

Geographic Tongue (Erythema Migrans)

♦

An inflammatory condition of the tongue primarily characterized by superficial microabscesses, this may be associated with psoriasis in the minority of cases (Fig. 24.16)

Fig. 24.16.

Subcorneal abscess formation is prominent in geographic tongue.

Lingual Thyroid

♦

This represents residual thyroid remaining on posterior dorsum or within the substance of the tongue, left from the embryologic descent of the thyroid enlarge

Lymphoepithelial Cyst

♦

This developmental anomaly is lined by squamous epithelium and surrounded by lymphoid follicles and is commonly seen in floor of the mouth, posterior/lateral tongue , and tonsillar region

Melanoacanthoma

♦

A suddenly progressing and regressing pigmented lesion of the buccal mucosa in African Americans

♦

Melanoacanthoma histologically demonstrates the presence of dendritic melanocytes within the spinous layer of epithelium

Nicotine Stomatitis

♦

Characterized by punctate erythematous areas surrounded by white zones on the palate of primarily pipe smokers

♦

Demonstrates a surface proliferation of squamous epithelium around a central salivary duct with associated inflammation

Oral Focal Mucinosis

♦

This represents a localized mass seen at any site in the mucosa characterized by the presence of abundant ground substance and flattening of the rete ridges of the epithelium

Palisaded, Encapsulated (Solitary, Circumscribed) Neuroma

♦

A discrete nodule usually less than 1 cm seen most frequently on lip vermilion and hard palate, the palisaded, encapsulated neuroma is characterized by well-demarcated proliferation of Schwann cells with faint palisaded arrangements and has axons present (Fig. 24.17)

Fig. 24.17.

Palisaded encapsulated neuroma is a circumscribed neural lesion and, thus, may be mistaken for schwannoma. Inset: Axonal proliferation distinguishes neuroma from nerve sheath tumor.

Salivary Duct Cyst

♦

The salivary duct cyst is a focal, small cystic lesion lined by salivary ductal epithelium seen most commonly in upper lip, buccal mucosa, and palate

Smokeless Tobacco-Induced Keratosis

♦

This represents a somewhat unique lesion occurring as a corrugated white patch seen in the location of placement of tobacco that demonstrates superficial epithelial necrosis and an amorphous hyalinized material histologically (Fig. 24.18)

Fig. 24.18.

Smokeless tobacco-induced keratosis is notable for acellular, subepithelial hyalinization.

Jaws

Nonodontogenic Cysts/Pseudocysts

Nasopalatine Cyst

Clinical

♦

Because it represents cystic degeneration of epithelial remnants of the nasopalatine duct, this cyst is seen in the anterior maxilla, midline, between the maxillary central incisors. It occurs in adults and may produce a swelling in the anterior hard palate

Radiograph

♦

The radiographic features are that of a pear- or heart-shaped well-demarcated radiolucency between the roots of the maxillary central incisors

Microscopic

♦

The lining consists of simple cuboidal, respiratory, or stratified squamous epithelium with prominent neurovascular bundles in the wall

Traumatic Bone Cavity

Clinical

♦

The traumatic bone cavity is exactly that, a cavity in bone possibly due to trauma with subsequent lysis of clot. It is most commonly seen in the posterior mandibular body with possible expansion and is often filled with serosanguineous fluid. Young adults are the typical population with a male predilection

Radiograph

♦

This represents a demarcated lucency with scalloping between tooth roots

Microscopic

♦

The microscopic features demonstrate a thin fibrous connective tissue wall with or without inflammation

Odontogenic Cysts

Dentigerous Cyst

Clinical

♦

This represents a developmental odontogenic cyst occurring around the crown of impacted tooth. It occurs most commonly in mandibular third molar region. The lining of this cyst can give rise to ameloblastoma, squamous cell carcinoma, or intraosseous mucoepidermoid carcinoma

Radiograph

♦

The radiographic presentation is that of a unilocular radiolucency around the crown of an impacted tooth

Microscopic

♦

Histologically, a bilayer of cuboidal cells or stratified squamous lining with myxomatous connective tissue containing small islands of odontogenic epithelium is seen (Fig. 24.19)

Fig. 24.19.

A bland lining of squamous cells with a loose connective tissue wall constitute the diagnostic features of a dentigerous cyst.

Odontogenic Keratocyst (Keratocystic Odontogenic Tumor)

Clinical

♦

This entity represents a peculiar keratinized odontogenic cyst arising from prefunctional dental lamina. The WHO currently classifies this as an odontogenic tumor rather than a cyst due to mutational characteristics. It is most common in the second to third decades and the posterior mandible. It can occur as multiple lesions, perhaps forming “daughter” cysts, making complete removal more difficult. This may be the feature that contributes to a 30% recurrence rate

♦

It is associated with the nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome (Gorlin–Goltz syndrome) that possesses the following characteristics:

Autosomal dominant, defect in ptch gene (chromosome 9)

Multiple basal cell carcinomas on non-or minimally sun-exposed skin

Palmar and plantar pits

Skeletal anomalies – bifid ribs, brachymetacarpalism, kyphoscoliosis, and calcified falx cerebri

Other tumors including medulloblastoma

Radiograph

♦

The common radiographic pattern is that of a multilocular radiolucency with possible expansion although it may be unilocular. The odontogenic keratocyst tends to demonstrate linear growth pattern within the jaw

Microscopic

♦

The odontogenic keratocyst demonstrates squamous epithelium with a luminal layer of corrugated parakeratin (Fig. 24.20). A uniform thickness of six to eight cell layers is apparent with a prominent basal layer with palisading nuclei

Fig. 24.20.

Odontogenic keratocysts are cytologically bland, locally aggressive cystic lesions.

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Keratinizing odontogenic cyst

This cyst demonstrates a luminal layer of orthokeratin, an indistinct basal layer and no association with the nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome

Apical Periodontal Cyst

Clinical

♦

This is an inflammatory cyst secondary to a pulpal infection, seen at the apex of a nonvital tooth

Radiograph

♦

The apical periodontal cyst appears as a unilocular lucency at the apex of tooth

Microscopic

♦

Histologically, proliferative squamous epithelial lining is seen with a wall of inflamed granulation tissue

Calcifying Odontogenic Cyst (Gorlin Cyst)

Clinical

♦

This developmental odontogenic cyst may demonstrate questionable neoplastic potential. It is seen in the second to third decades and the anterior aspects of the jaws. It may also occur in an extraosseous fashion on the gingiva. It has a low recurrence rate of 10% and may be associated with ameloblastomas

Radiograph

♦

The Gorlin cyst appears as a unilocular or multilocular expansile radiolucency with intermixed calcifications and may be associated with an odontoma

Microscopic

♦

A lining of odontogenic epithelium is seen with a basal layer of columnar cells with palisading nuclei. Prominent in this epithelium is the presence of “ghost” cells, squamous cells with abundant cytoplasm and central voids lacking nuclei (Fig. 24.21). Variable amounts of odontogenic product, “dentinoid,” may also be present

Fig. 24.21.

“Ghost” cells, prematurely keratinizing epithelial cells without nuclei, are the hallmark of the calcifying odontogenic cyst .

Dentinogenic Ghost Cell Tumor (Included Here given Similarity to Gorlin Cyst)

♦

This represents a noncystic neoplasm with microscopic characteristics similar to the Gorlin cyst. These represent more aggressive lesions, and rare malignant counterparts have been reported

Reactive/Nonneoplastic Disease

Cementoosseous Dysplasia

Clinical

♦

This peculiar condition is a nonneoplastic proliferation of periodontal ligament origin. Typically asymptomatic, it is found on routine radiographic survey. It demonstrates a predilection for African American females in the third to fifth decades. It occurs in a variety of clinical settings including periapical, which is seen around apices of mandibular anterior teeth; focal which is a single lesion seen in the posterior mandible; and florid which are multiple lesions seen in at least two quadrants. It does not require removal, only identification. However, patients are at risk for osteomyelitis as the lesions calcify and become avascular

Radiograph

♦

These lesions appear as relatively well-demarcated , mixed radiolucent/radiopaque lesions

Microscopic

♦

Cementoosseous dysplasia appears as curetted fragments with high cellularity of spindle-shaped mesenchymal cells . These cells are mixed with calcified product, often small sphericals of cementum and/or bone

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Central cementoossifying fibroma

Field for field this is a histologically identical lesion although it represents a benign neoplasm. It can be distinguished by radiographic (well-demarcated, expansile lucency) and surgical findings (avascular, delineated solid mass)

Odontoma

Clinical

♦

The odontoma is a hamartomatous process of the odontogenic apparatus that is seen primarily in the first two decades of life. It presents as two types: compound, which forms toothlike structures most commonly in the anterior maxilla, and complex, which forms a mass of calcified product in the posterior jaws

Radiograph

♦

The compound odontoma demonstrates multiple toothlike structures with radiolucent rim. The complex odontoma exhibits a central mass of opaque material surrounded by radiolucent rim

Microscopic

♦

Odontomas contain a mixture of enamel, enamel matrix, dentin, pulp, and follicular tissue, either in appropriate context or haphazardly arranged

“Giant Cell” and Giant Cell-Rich Lesions

Central Giant Cell Granuloma

Clinical

♦

This represents a central lesion seen most commonly in females in the early second decade. It demonstrates a propensity to occur in the anterior mandible crossing the midline. Its etiology is unknown, and it exhibits a recurrence rate of 15%. Peripheral variant is seen most commonly on the mandibular gingiva or alveolar mucosa as a purplish, exophytic mass

Radiograph

♦

Typically, this occurs as a multilocular radiolucency although it can be unilocular. Expansion, tooth movement, and resorption are all possible sequelae

Microscopic

♦

Microscopically, the giant cell granuloma is characterized by a cellular spindle cell framework with clusters of multinucleated giant cells (osteoclasts), extravasated erythrocytes, and hemosiderin

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Giant cell lesions of the jaws constitute an area of confusion

Much has been written as to whether giant cell granulomas, giant cell tumors, and aneurysmal bone cysts represent the same lesion, entities on a continuum, or separate and distinct conditions

♦

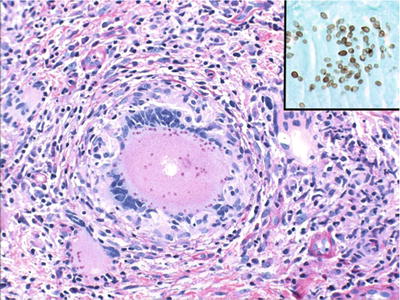

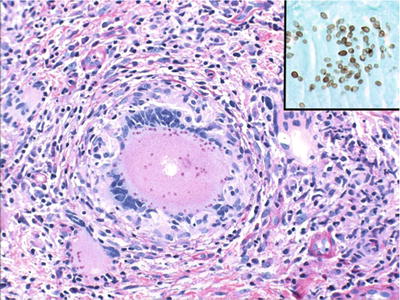

The brown tumor of hyperparathyroidism is indistinguishable from the central giant cell granuloma , and, accordingly, this systemic disease must be excluded (Fig. 24.22)

Fig. 24.22.

Osteitis fibrosa cystica (“brown tumor”) results from hyperparathyroidism and is histologically indistinguishable from giant cell reparative granuloma. Inset: Reactive osteoid may be prominent.

Giant Cell Tumor

♦

This is a true neoplasm that rarely occurs in the oral cavity and is discussed in detail in Chapter 21

Aneurysmal Bone Cyst

Clinical

♦

The aneurysmal bone cyst is seen most commonly before the age of 20 and does not exhibit a gender predilection. The mandible is more commonly afflicted by this rapidly expansile lesion. Often substantial recurrence is due to incomplete removal. This may occur in concert with other pathologic entities including fibroosseous lesions and osseous neoplasms. Its etiology is unknown although trauma is suspected

Radiograph

♦

A symmetrically expansile, unilocular radiolucency with a thin rim of residual bone is the typical manifestation although it can be multilocular

Microscopic

♦

Large pools of extravasated erythrocytes surrounded by cellular mesenchymal tissue with giant cells bordering the cavities are the salient histologic features. The cavities are not lined by endothelial cells

Cherubism

Clinical

♦

Cherubism represents an inherited disorder, transferred as an autosomal dominant condition due to a defect on chromosome 4p16. It exhibits complete penetrance in males and incomplete penetrance in females. The usual age at diagnosis is 5 years. Bilateral expansion of the maxilla and mandible is seen clinically, producing chubby cheeks, hence the name. Cherubism typically regress at puberty without surgery, although it may require surgical intervention if grossly deforming

Radiograph

♦

Bilateral, expansile multilocular radiolucencies in the posterior mandible and maxilla are the hallmarks of this disease

Microscopic

♦

Cellular, myxomatous mesenchymal tissue with intermixed giant cells comprises the majority of the lesion, whereas perivascular cuffing of hyaline material represents a useful clue to the diagnosis

Benign Neoplasms

Ameloblastoma

Clinical

♦

This is the most common epithelial odontogenic neoplasm, recapitulating the enamel organ. Ameloblastoma occurs most commonly in the third to fifth decades of life and presents as painless expansion usually in the posterior mandible. Typically aggressive, the ameloblastoma demonstrates up to a 90% recurrence rate with curettage and a 15–20% recurrence rate with resection. Rare examples of metastasis have been reported (malignant ameloblastoma). Peripheral variant represents an ameloblastoma occurring in an extraosseous location (Fig. 24.23)

Fig. 24.23.

Peripheral ameloblastoma resembles its intraosseous counterpart. Note overlying mucosa.

Radiograph

♦

Either an expansile unilocular or multilocular (soap bubble) radiolucency is the classic radiographic presentation. Perforation of the cortical plate is often seen

Microscopic

♦

Two histologic variants are typically seen. The unicystic ameloblastoma demonstrates cystic areas with luminal proliferation of the plexiform pattern of ameloblastoma. The conventional ameloblastoma may exhibit a variety of patterns including follicular, plexiform, acanthomatous, granular cell, basal cell, and desmoplastic (Fig. 24.24). Both are typically characterized by a peripheral layer of columnar cells with reverse polarization and nuclear palisading. Central zones of stellate cells with exaggerated intercellular spacing are seen in more solid areas although the conventional ameloblastoma can be predominantly cystic

Fig. 24.24.

Ameloblastoma may show prominent cystic change . Peripheral cells exhibit nuclear palisading with reverse polarization; the latter is not conspicuous in this example.

Adenomatoid Odontogenic Tumor

Clinical

♦

This benign neoplasm of the odontogenic apparatus forms gland-like spaces surrounded by odontogenic epithelium. Most commonly, it is seen in the anterior maxilla associate with an impacted canine tooth and demonstrates a 2:1 female predilection. Enucleation tends to be a curative surgical procedure

Radiograph

♦

The radiographic presentation is that of a pericoronal lucency with or without calcification

Microscopic

♦

Microscopically, this neoplasm is characterized by a cystic lesion with proliferation of epithelial cells demonstrating whorls and focal gland-like spaces lined by columnar cells. Dentinoid and amyloid may also be present

Calcifying Epithelial Odontogenic Tumor (Pindborg Tumor)

Clinical

♦

This benign epithelial odontogenic neoplasm can mimic malignancy due to its cellular pleomorphism. It is seen mostly as a slowly progressing expansile mass in the posterior mandible in the fourth to sixth decades. It demonstrates a 15% recurrence rate after removal

Radiograph

♦

The Pindborg tumor appears as a well-demarcated multilocular radiolucency with calcifications (“driven snow” appearance)

Microscopic

♦

The microscopic appearance is that of sheets of polygonal epithelial cells with prominent intercellular bridging. Marked pleomorphism is often seen but without mitotic activity. Spherical laminated calcifications (Liesegang rings) and amyloid are also present

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Squamous cell carcinoma

Mitoses, invasive growth, and an ill-defined radiographic appearance differentiate the two entities

Squamous Odontogenic Tumor

Clinical

♦

This, too, is a benign epithelial odontogenic neoplasm that can mimic squamous cell carcinoma at the histologic level. Present in the third to fourth decades, it occurs in the posterior jaws as an expansile mass. Treated appropriately, it rarely recurs

Radiograph

♦

The characteristic appearance is that of a semilunar radiolucency arising in alveolar bone

Microscopic

♦

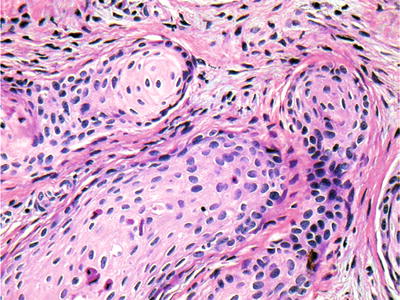

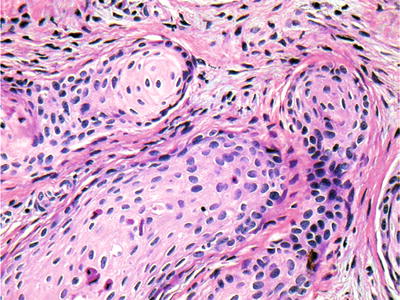

Islands of squamous epithelial cells without a prominent basal layer are the histologic signature. Although worrisome, no atypia, mitotic figures, or central keratinization is seen (Fig. 24.25). The islands may demonstrate central cystic degeneration

Fig. 24.25.

Squamous odontogenic tumors demonstrate islands of squamous epithelium without atypical features or mitoses.

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Squamous cell carcinoma

Should demonstrate pleomorphism, mitoses, and keratinization, all of which are lacking in squamous odontogenic tumor

♦

Ameloblastoma, acanthomatous type

Prominent palisading arrangement of basal cell layer is the distinguishing characteristic

Ameloblastic Fibroma

Clinical

♦

This represents a mixed odontogenic tumor with coexistent epithelial and mesenchymal components. It occurs in the first and second decades, with the majority in the posterior mandible impeding the eruption of the permanent first molar. Even with appropriate surgery, a 10–20% recurrence rate is seen

Radiograph

♦

Radiographically, a unilocular or multilocular radiolucency associated with an impacted tooth is the typical presentation

Microscopic

♦

A bilayer of odontogenic epithelium embedded within cellular myxomatous mesenchymal tissue constitutes the diagnostic features (Fig. 24.26)

Fig. 24.26.

Bilayers of ameloblastic cells embedded in a myxomatous mesenchymal framework characterize ameloblastic fibroma.

Cementoblastoma

Clinical

♦

This represents the benign odontogenic counterpart to the osteoblastoma. Most common in the first two decades , it occurs in the mandibular first molar area and is characterized by pain and swelling. It can recur if incompletely removed

Radiograph

♦

An opaque symmetrical mass merging imperceptibly with the root of the tooth and possessing a radiolucent peripheral rim is the reproducible radiographic feature

Microscopic

♦

Peripheral radiation of cemental product punctuated by prominent cementoblasts, cementoclasts, and vascularity is the salient characteristic . Because of these features, it is thought to represent the odontogenic analog of osteoblastoma

Central Cementoossifying Fibroma

Clinical

♦

The central cementoossifying fibroma is a benign product-forming neoplasm of periodontal ligament origin. It occurs in the second to fourth decades with a female predilection. The posterior mandibular is most common, and it manifests as a slowly progressing swelling. It rarely recurs when surgically removed

Radiograph

♦

Typically, this is a well-demarcated unilocular radiolucency with characteristic bowing of the inferior border of the mandible. Although product forming histologically, it usually demonstrates only small flecks of calcification at the radiographic level

Microscopic

♦

This is an avascular, well-delineated mass of cellular mesenchymal tissue demonstrating spindle-shaped cells arranged in whorls and fascicles. Usually, only limited punctate calcifications are interspersed within the cellular tissue

Odontogenic Fibroma

Clinical

♦

This benign neoplasm is comprised primarily of odontogenic mesenchymal tissue with variable epithelium and calcification. It can be central or peripheral and occurs at an average age of 40. A prominent female propensity is seen, and the posterior maxilla is most commonly afflicted. On rare occasions, it may be associated with a peculiar cleft defect in the maxilla. Only rare recurrences have been reported

Radiograph

♦

The radiographic appearance is that of a unilocular or multilocular radiolucency, often with expansion

Microscopic

♦

The simple type appears as a collagenous mesenchymal proliferation with evenly dispersed bland spindle cells. The WHO type demonstrates cellular mesenchymal tissue with strands of odontogenic epithelium and variable calcified product

Malignant Neoplasms

Ameloblastic Carcinoma

Clinical

♦

This is an odontogenic epithelial malignancy with ameloblastic differentiation. It occurs most commonly in the fourth decade with a mandibular predilection. It metastasizes preferentially to the lungs and demonstrates a <50% 5-year survival rate

Radiograph

♦

It manifests as an ill-defined, lytic lesion with a variable growth rate

Microscopic

♦

The microscopic appearance is that of an epithelial proliferation with peripheral cells demonstrating columnar morphology with reverse polarization (Fig. 24.27). Prominent pleomorphism and mitotic activity are usually seen

Fig. 24.27.

Cellular pleomorphism , as seen here, distinguishes ameloblastic carcinoma from ameloblastoma.

Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Clinical

♦

This is a central odontogenic carcinoma demonstrating squamous differentiation. Seen in adults, it demonstrates a mandibular predilection. Its overall behavior is dependent on grade and stage. However, most of them represent local disease and are amenable to surgery

Radiograph

♦

This may occur as a poorly defined lytic lesion or arise from a preexisting, long-standing odontogenic cyst

Microscopic

♦

This entity demonstrates the typical features of squamous cell carcinoma; accordingly, one must rule out metastasis or an antral primary if occurring in the maxilla

Clear Cell Odontogenic Carcinoma

Clinical

♦

This odontogenic malignancy is composed of odontogenic epithelium with prominent cytoplasmic clearing. Occurring in the sixth decade or later, it is most common in the mandible. Although metastasis is known to occur, it is not common. However, multiple recurrences with locally aggressive behavior are the typical pattern

Radiograph

♦

The clear cell odontogenic carcinoma manifests as an ill-defined lucency with bone destruction

Microscopic

♦

Strands and sheets of cells with odontogenic differentiation and cytoplasmic clearing are seen. These clear cells may or may not demonstrate glycogen with PAS stains. The stroma is often cellular with hyalinization around the epithelium

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Metastatic renal cell carcinoma

Prominent vascular stroma without the stromal cellularity should help delineate the two

Osteosarcoma

Clinical

♦

Osteosarcoma of the jaws demonstrates a differentdemonstrates a different character relative to osteosarcoma of the long bones in the following ways:

Tends to occur at a later age, average ~33 years

Tends to be lower grade

Tends to be chondroblastic

♦

The survival rate has remained relatively unchanged even with the newer modalities of treatment. Osteosarcomas of the mandible demonstrate a 40% 5-year survival, and the maxilla demonstrates a 25% 5-year survival

Radiograph

♦

Osteosarcomas tend to be ill-defined mixed radiolucent/opaque lesions, perhaps with a radiating calcified product (sunburst effect). Localized widening of the periodontal ligament space may be an early manifestation

Microscopic

♦

As in the long bones, osteosarcoma is characterized by tumor bone punctuated by a frankly sarcomatous mesenchymal proliferation. Cartilage is often seen in osteosarcoma of the jaws and should always be treated with suspicion

Chondrosarcoma

Clinical

♦

Some have speculated otherwise, but these do occur in the jaws. The average age at diagnosis is ~30 years. Chondrosarcomas of the jaws tend to be slow-growing lesions and tend to be low grade

Radiograph

♦

Chondrosarcomas demonstrate many of the same radiographic features of osteosarcoma although the product tends to be less linear and more rounded

Microscopic

♦

Generally, mature type cartilage is seen with minimally atypical chondrocytes and chondroblasts . Because of this, chondrosarcomas of the jaws are often underdiagnosed as benign conditions

Mesenchymal Chondrosarcoma

Clinical

♦

A rare tumor, the mesenchymal chondrosarcoma is seen in the jaws as one of its more preferential locations. It may also arise in soft tissue and is seen most commonly in the second and third decades

Microscopic

♦

Undifferentiated stromal cells with islands of mature cartilage are the histologic hallmarks. The stromal component may resemble “small blue cell tumors” and/or hemangiopericytoma (“staghorn” vascular pattern). Mitotic figures may be scarce to frequent, and the cartilaginous foci vary from prominent to scarce

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Distinctio n from Ewing sarcoma, hemangiopericytom a, and others relies upon recognition of cartilaginous foci

Metastatic Disease

Clinical

♦

Carcinomas of the breast, lung, prostate, and renal origin represent the most common metastases to the jaws. Fully one-third of patients are unaware of primary tumor at time of diagnosis. These often present with pain and/or paresthesia

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree