THE HAEMOPHILUS SPECIES

This is a group of small, gram-negative, pleomorphic bacteria that require enriched media, usually containing blood or its derivatives, for isolation. Haemophilus influenzae is a major human pathogen; Haemophilus ducreyi, a sexually transmitted pathogen, causes chancroid; six other Haemophilus species are among the normal microbiota of mucous membranes and only occasionally cause human disease. Haemophilus aphrophilus and Haemophilus paraphrophilus have been combined into a single species Aggregatibacter aphrophilus; likewise, Haemophilus segnis is now a member of the Aggregatibacter genus (Table 18-1).

| Requires | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Species | X | V | Hemolysis |

| Haemophilus influenzae (H aegyptius) | + | + | − |

| Haemophilus parainfluenzae | − | + | − |

| Haemophilus ducreyi | + | − | − |

| Haemophilus haemolyticus | + | + | + |

| Aggregatibacter aphrophilusa | − | +/− | − |

| Haemophilus paraphrophaemolyticus | − | + | + |

| Aggregatibacter segnisb | − | + | − |

HAEMOPHILUS INFLUENZAE

H influenzae is found on the mucous membranes of the upper respiratory tract in humans. It is an important cause of meningitis in unvaccinated children and causes upper and lower respiratory tract infections in children and adults.

In specimens from acute infections, the organisms are short (1.5 μm) coccoid bacilli, sometimes occurring in pairs or short chains. In cultures, the morphology depends both on the length of incubation and on the medium. At 6–8 hours in rich medium, the small coccobacillary forms predominate. Later, there are longer rods and very pleomorphic forms.

Some organisms in young cultures (6–18 hours) on enriched medium express a definite capsule. The capsule is the antigen used for “typing” H influenzae (see later discussion).

On chocolate agar, flat, grayish, translucent colonies with diameters of 1–2 mm are present after 24 hours of incubation. IsoVitaleX in media enhances growth. H influenzae does not grow on sheep blood agar except around colonies of staphylococci (“satellite phenomenon”). Haemophilus haemolyticus and Haemophilus parahaemolyticus are hemolytic variants of H influenzae and Haemophilus parainfluenzae, respectively.

Identification of organisms of the Haemophilus group depends partly on demonstrating the need for certain growth factors called X and V. Factor X acts physiologically as hemin; factor V can be replaced by nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) or other coenzymes. Colonies of staphylococci on sheep blood agar cause the release of NAD, yielding the satellite growth phenomenon. The requirements for X and V factors of various Haemophilus species are listed in Table 18-1. Carbohydrate fermentation is useful in species identification as is the presence or absence of hemolysis.

In addition to serotyping on the basis of capsular polysaccharides (see later discussion), H influenzae and H parainfluenzae can be biotyped on the basis of the production of indole, ornithine decarboxylase, and urease. Most of the invasive infections caused by H influenzae belong to biotypes I and II (there are a total of eight).

Encapsulated H influenzae contains capsular polysaccharides (molecular weight >150,000) of one of six types (a–f). The capsular antigen of type b is a polyribitol ribose phosphate (PRP). Encapsulated H influenzae can be typed by slide agglutination, coagglutination with staphylococci, or agglutination of latex particles coated with type-specific antibodies. A capsule swelling test with specific antiserum is analogous to the quellung test for pneumococci. Typing can also be done by immunofluorescence. Most H influenzae organisms in the normal microbiota of the upper respiratory tract are not encapsulated and are referred to as nontypeable (NTHi).

The somatic antigens of H influenzae consist of outer membrane proteins. Lipooligosaccharides (endotoxins) share many structures with those of neisseriae.

H influenzae produces no exotoxin. The nonencapsulated organism is a regular member of the normal respiratory microbiota of humans. The capsule is antiphagocytic in the absence of specific anticapsular antibodies. The polyribose phosphate capsule of type b H influenzae is the major virulence factor.

The carrier rate in the upper respiratory tract for H influenzae type b was 2–5% in the prevaccine era and is now less than 1%. The carrier rate for NTHi is 50–80% or higher. Type b H influenzae causes meningitis, pneumonia and empyema, epiglottitis, cellulitis, septic arthritis, and occasionally other forms of invasive infection. NTHi tends to cause chronic bronchitis, otitis media, sinusitis, and conjunctivitis after breakdown of normal host defense mechanisms. The carrier rate for the encapsulated types a and c to f is low (1–2%), and these capsular types rarely cause disease. Although type b can cause chronic bronchitis, otitis media, sinusitis, and conjunctivitis, it does so much less commonly than NTHi. Similarly, NTHi only occasionally causes invasive disease (~5% of cases).

H influenzae type b enters by way of the respiratory tract. There may be local extension with involvement of the sinuses or the middle ear. H influenzae, mostly nontypeable, and pneumococci are two of the most common etiologic agents of bacterial otitis media and acute sinusitis. Lower respiratory tract infections such as bronchitis and pneumonia may be seen in patients with conditions that diminish mucociliary clearance. Examples include smoking, chronic obstructive lung disease, and cystic fibrosis. Encapsulated organisms may reach the bloodstream and be carried to the meninges or, less frequently, may establish themselves in the joints to produce septic arthritis. Before the use of the conjugate vaccine, H influenzae type b was the most common cause of bacterial meningitis in children aged 5 months to 5 years in the United States. Clinically, it resembles other forms of childhood meningitis, and diagnosis rests on bacteriologic demonstration of the organism.

Occasionally, a fulminating obstructive laryngotracheitis with swollen, cherry-red epiglottis develops in young children and requires prompt tracheostomy or intubation as a lifesaving procedure. Pneumonitis and epiglottitis caused by H influenzae may follow upper respiratory tract infections in small children and old or debilitated people. Adults may have bronchitis or pneumonia caused by H influenzae.

Specimens consist of expectorated sputum and other types of respiratory specimens, pus, blood, and spinal fluid for smears and cultures depending on the source of the infection.

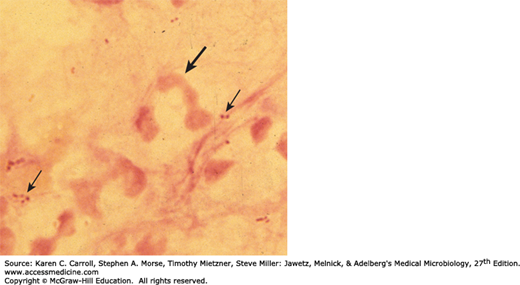

Commercial kits are available for immunologic detection of H influenzae antigens in spinal fluid. These antigen detection tests generally are not more sensitive than a Gram stain and therefore are not widely used, especially because the incidence of H influenzae meningitis is so low. Their use is discouraged in all but limited resource settings where disease prevalence remains high. A Gram stain of H influenzae in sputum is depicted in Figure 18-1. Nucleic acid amplification methods have been developed by some laboratories and may soon be commercially available for direct detection from cerebrospinal fluid and lower respiratory tract infections.

Specimens are grown on IsoVitaleX-enriched chocolate agar until typical colonies appear (see above). H influenzae is differentiated from related gram-negative bacilli by its requirements for X and V factors and by its lack of hemolysis on blood agar (see Table 18-1).

Tests for X (heme) and V (nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide) factor requirements can be done in several ways. The Haemophilus species that require V factor grow around paper strips or disks containing V factor placed on the surface of agar that has been autoclaved before the blood was added (V factor is heat labile). Alternatively, a strip containing X factor can be placed in parallel with one containing V factor on agar deficient in these nutrients. Growth of Haemophilus in the area between the strips indicates requirement for both factors. A better test for X factor requirement is based on the inability of H influenzae (and a few other Haemophilus species) to synthesize heme from δ-aminolevulinic acid. The inoculum is incubated with the δ-aminolevulinic acid. Haemophilus organisms that do not require X factor synthesize porphobilinogen, porphyrins, protoporphyrin IX, and heme. The presence of red fluorescence under ultraviolet light (~360 nm) indicates the presence of porphyrins and a positive test result. Haemophilus species that synthesize porphyrins (and thus heme) are not H influenzae (see Table 18-1).

Infants younger than age 3 months may have serum antibodies transmitted from their mothers. During this time, H influenzae infection is rare, but subsequently, the antibodies are lost. Children often acquire H influenzae infections, which are usually asymptomatic but may be in the form of respiratory disease or meningitis. H influenzae was the most common cause of bacterial meningitis in children from 5 months to 5 years of age until the early 1990s when the conjugate vaccines became available (see later discussion). By age 3–5 years, many unimmunized children have naturally acquired anti-PRP antibodies that promote complement-dependent bactericidal killing and phagocytosis. Immunization of children with H influenzae type b conjugate vaccine induces the same antibodies.

There is a correlation between the presence of bactericidal antibodies and resistance to major H influenzae type b infections. However, it is not known whether these antibodies alone account for immunity. Pneumonia or arthritis caused by infection with H influenzae can develop in adults with such antibodies.

The mortality rate for individuals with untreated H influenzae meningitis may be up to 90%. Many strains of H influenzae type b are susceptible to ampicillin, but up to 25% produce a β-lactamase under control of a transmissible plasmid and are resistant. Essentially all strains are susceptible to the third-generation cephalosporins and carbapenems. Cefotaxime given intravenously gives excellent results. Prompt diagnosis and antimicrobial therapy are essential to minimize late neurologic and intellectual impairment. Prominent among late complications of H influenzae type b meningitis is the development of a localized subdural accumulation of fluid that requires surgical drainage. Up to 27% of NTHi in the United States also produce β-lactamases.

Encapsulated H influenzae type b is transmitted from person to person by the respiratory route. H influenzae type b disease can be prevented by administration of Haemophilus b conjugate vaccine to children. Currently, there are three PRP polysaccharide-protein monovalent conjugate vaccines (polysaccharide linked to outer membrane protein complex) available for use in the United States: PRP-OMP (PedvaxHIB, Merck and Co., Inc.), PRP-T (ActHIB, Sanofi Pasteur, Inc.), and PRP-T (Hiberix, GlaxoSmithKline). In PRP-OMP, the outer membrane protein complex of Neisseria meningitidis serogroup B is the protein conjugate, whereas for PRP-T it is tetanus toxoid. There are also three combination vaccines that contain H influenzae type b conjugate vaccine. These are: PRP-OMP-HepB (Merck and Co., Inc.), DTaP-IPV/PRP-T (diphtheria, acellular pertussis, and inactivated polio are added to PRP-T; Sanofi Pasteur), and MenCY/PRP-T (meningococcal C and Y vaccine added to PRP-T; GlaxoSmithKline). The reader is referred to the reference by Briere for a complete discussion of these vaccines. Beginning at age 2 months, all children should be immunized with one of the conjugate vaccines. Depending on which vaccine product is chosen, the series consists of three doses at 2, 4, and 6 months of age or two doses given at 2 and 4 months of age. An additional booster dose is given sometime between 12 and 18 months of age. Monovalent conjugate vaccines can be given at the time of other vaccine administration such as DTaP (diphtheria, tetanus, and acellular pertussis). Widespread use of H influenzae type b vaccine has reduced the incidence of H influenzae type b meningitis in children by more than 95%. The vaccine reduces the carrier rates for H influenzae type b.

Contact with patients with H influenzae type b clinical infection poses little risk for adults but presents a definite risk for nonimmune siblings and other nonimmune children younger than age 4 years who are close contacts. Prophylaxis with rifampin is recommended for such children.

HAEMOPHILUS AEGYPTIUS

This organism was formerly called the Koch-Weeks bacillus and it is associated with highly communicable form of conjunctivitis (pinkeye) in children. Haemophilus aegyptius is closely related to H influenzae biotype III, the causative agent of Brazilian purpuric fever. The latter is a disease of children characterized by fever, purpura, shock, and death. In the past, these infections were mistakenly attributed to H aegyptius.

AGGREGATIBACTER APHROPHILUS

Organisms belonging to the species H aphrophilus and H paraphrophilus have been combined into the same species, and the name was changed to A aphrophilus. H segnis and Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans have also been added to the genus Aggregatibacter. A aphrophilus isolates are often encountered as causes of infective endocarditis and pneumonia. These organisms are present in the oral cavity as part of the normal respiratory microbiota along with other members of the HACEK (Haemophilus species, Actinobacillus/Aggregatibacter species, Cardiobacterium hominis, Eikenella corrodens, and Kingella kingae) group (see Chapter 16).

HAEMOPHILUS DUCREYI

H ducreyi causes chancroid (soft chancre), a sexually transmitted disease. Chancroid consists of a ragged ulcer on the genitalia, with marked swelling and tenderness. The regional lymph nodes are enlarged and painful. The disease must be differentiated from syphilis, herpes simplex infection, and lymphogranuloma venereum.

The small, gram-negative rods occur in strands in the lesions, usually in association with other pyogenic microorganisms. H ducreyi requires X factor but not V factor. It is grown best from scrapings of the ulcer base that are inoculated onto chocolate agar containing 1% IsoVitaleX and vancomycin, 3 μg/mL; the agar is incubated in 10% CO2 at 33°C. Nucleic acid amplification methods are more sensitive than culture. There is no permanent immunity after chancroid infection. The recommended treatment by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is 1 g of azithromycin taken orally. Other treatment regimens include intramuscular ceftriaxone, oral ciprofloxacin, or oral erythromycin; healing results in 2 weeks.

OTHER HAEMOPHILUS SPECIES

H haemolyticus is the most markedly hemolytic organism of the group in vitro; it occurs both in the normal nasopharynx and in association with rare upper respiratory tract infections of moderate severity in childhood. H parainfluenzae resembles H influenzae and is a normal inhabitant of the human respiratory tract; it has been encountered occasionally in infective endocarditis and in urethritis.

Haemophilus species are pleomorphic, gram-negative rods that require either X (hemin) or V (NAD) factors or both for growth. Most of the species in this genus are colonizers of the upper respiratory tract of humans.

H influenzae is the major pathogen in the group, and strains that are encapsulated, especially serotype b, are more virulent, causing invasive disease, including bacteremia and meningitis in unprotected individuals.

H influenzae type b, once a significant cause of childhood morbidity and mortality, is now rare in industrialized countries that routinely vaccinate children with one of two available conjugate vaccines.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree