distention, and intermittent periumbilical cramping pain. In a large-bowel obstruction, abdominal pain is milder and more constant than that associated with a small-bowel obstruction and is usually located lower in the abdomen.

membrane. Fever and cervical lymphadenopathy are also common.

The glare of headlights may blind the patient, making nighttime driving impossible. Other features include blurred vision, impaired visual acuity, and lens opacity, all of which develop gradually.

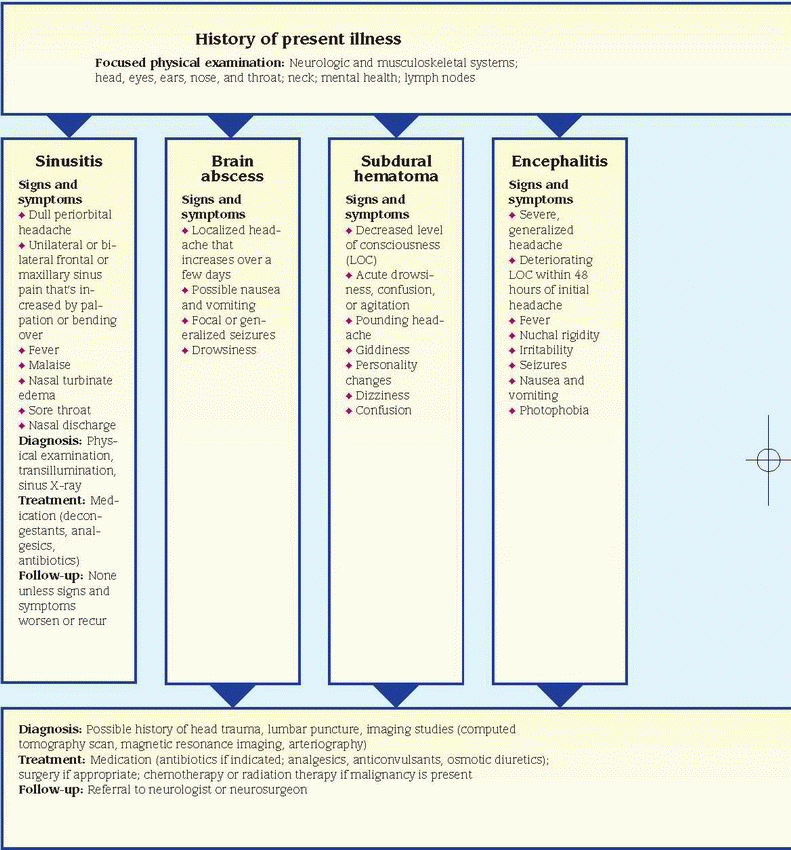

abscess remains encapsulated, these signs may not appear.

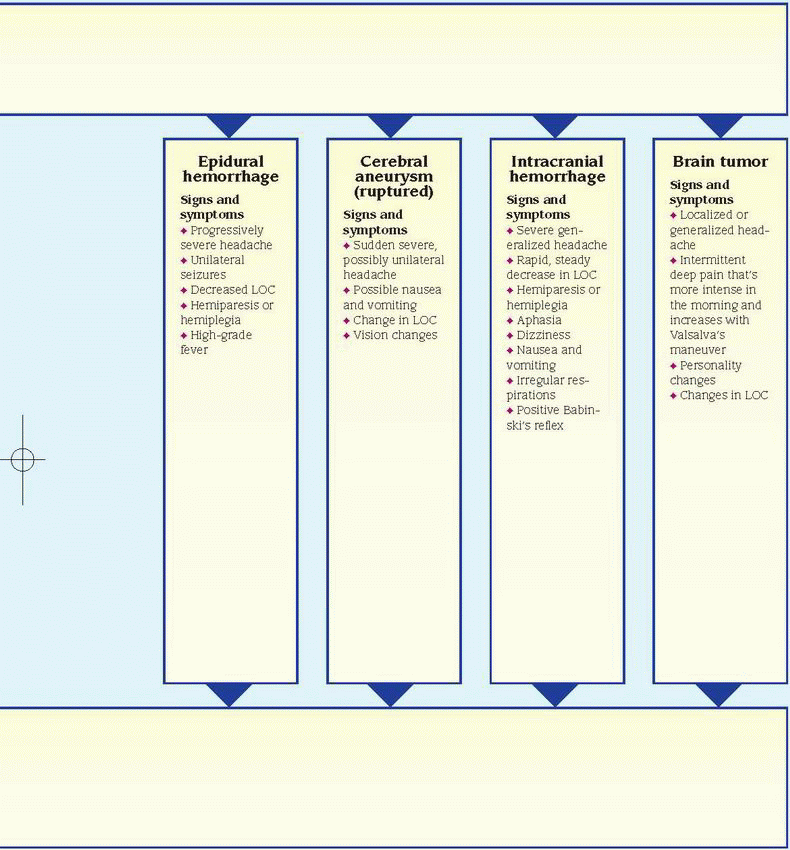

Characteristics | Muscle-contraction headaches | Vascular headaches |

Incidence | ♦ Most common type, accounting for 80% of all headaches | ♦ More common in women and those with a family history of migraines ♦ Onset after puberty |

Precipitating factors | ♦ Stress, anxiety, tension, improper posture, and body alignment ♦ Prolonged muscle contraction without structural damage ♦ Eye, ear, and paranasal sinus disorders that produce reflex muscle contractions | ♦ Hormone fluctuations ♦ Alcohol ♦ Emotional upset ♦ Too little or too much sleep ♦ Foods, such as chocolate, cheese, monosodium glutamate, and cured meats; caffeine withdrawal ♦Weather changes, such as shifts in barometric pressure |

Intensity and duration | ♦ Produce an aching tightness or a band of pain around the head, especially in the neck and in occipital and temporal areas ♦ Occur frequently and usually last for several hours | ♦ May begin with an awareness of an impending migraine or a 5- to 15-minute prodrome of neurologic deficits, such as visual disturbances, dizziness, unsteady gait, or tingling of the face, lips, or hands ♦ Produce severe, constant, throbbing pain that is typically unilateral and may be incapacitating ♦ Last for 4 to 6 hours |

Associated signs and symptoms | ♦ Tense neck and facial muscles | ♦ Anorexia, nausea, and vomiting ♦ Occasionally, photophobia, sensitivity to loud noises, weakness, and fatigue ♦ Depending on the type (cluster headache or classic, common, or hemiplegic migraine), possibly chills, depression, eye pain, ptosis, tearing, rhinorrhea, diaphoresis, and facial flushing |

Alleviating factors | ♦ Mild analgesics, muscle relaxants, or other drugs during an attack ♦ Measures to reduce stress, such as biofeedback, relaxation techniques, and counseling; posture correction to prevent attacks | ♦ Methysergide and propranolol to prevent vascular headache ♦ Ergot alkaloids or serotoninreceptor drugs at the first sign of a migraine ♦ Rest in a quiet, darkened room ♦ Elimination of irritating foods from diet |

Associated signs and symptoms include personality changes, altered LOC, motor and sensory dysfunction, and eventually signs of increased ICP, such as vomiting, increased systolic blood pressure, and widened pulse pressure.

may lose consciousness immediately or display a variably altered LOC. Depending on the severity and location of the bleeding, he may also exhibit nausea and vomiting; signs and symptoms of meningeal irritation, such as nuchal rigidity and blurred vision; hemiparesis; and other features.

vomiting, seizures, decreased sensation, irregular respirations, positive Babinski’s reflex, decorticate or decerebrate posture, and increased blood pressure.

Listeriosis during pregnancy may lead to premature delivery, infection of the neonate, or stillbirth.

Listeriosis during pregnancy may lead to premature delivery, infection of the neonate, or stillbirth.arteries are tender, swollen, nodular, and sometimes erythematous.

Herbal remedies, such as St. John’s wort, ginseng, and ephedra (ma huang), can cause various adverse reactions, including headaches. (Note: The FDA has banned the sale of dietary supplements containing ephedra because they pose an unreasonable risk of injury or illness.)

Herbal remedies, such as St. John’s wort, ginseng, and ephedra (ma huang), can cause various adverse reactions, including headaches. (Note: The FDA has banned the sale of dietary supplements containing ephedra because they pose an unreasonable risk of injury or illness.)than age 50. Other physiologic causes of hearing loss include cerumen (earwax) impaction; barotitis media (unequal pressure on the eardrum) associated with descent in an airplane or elevator, diving, or close proximity to an explosion; and chronic exposure to noise over 90 decibels, which can occur on the job, with certain hobbies, or from listening to live or recorded music.

It usually bleeds easily when manipulated. Late features include ear pain, dizziness, and total unilateral deafness.

|

|

|

anti-inflammatory drugs or alcohol. In a patient with esophageal varices, hematemesis may be due to trauma from swallowing hard or partially chewed food. (See Rare causes of hematemesis.)

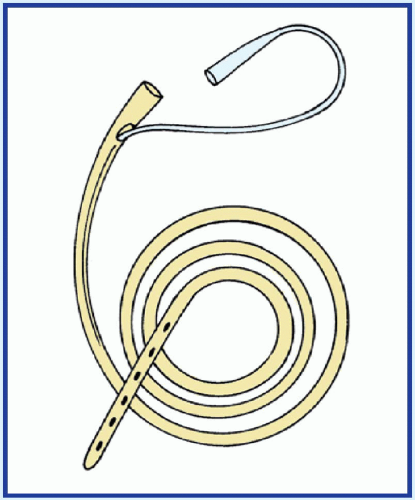

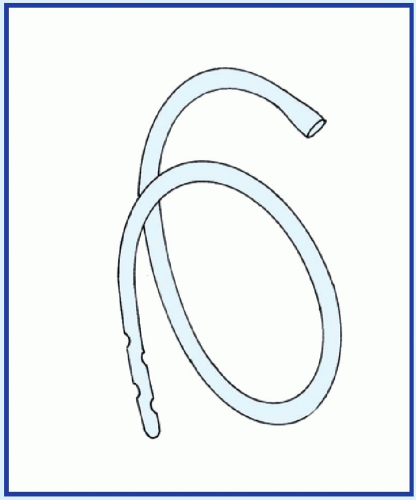

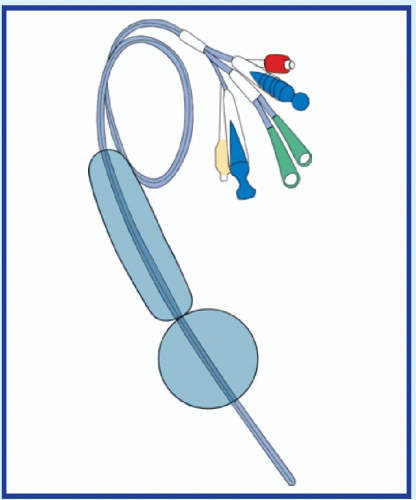

If the patient has massive hematemesis, check his vital signs. If you detect signs of shock—such as tachypnea, hypotension, and tachycardia—place the patient in a supine position, and elevate his feet 20 to 30 degrees. Start a large-bore I.V. catheter for emergency fluid replacement. Also, obtain a blood sample for typing and crossmatching, hemoglobin level, and hematocrit, and administer oxygen. Emergency endoscopy may be necessary to locate the source of bleeding. Prepare to insert a nasogastric (NG) tube for suction or iced lavage. A Sengstaken-Blakemore tube may be used to compress esophageal varices. (See Managing hematemesis with intubation, page 356.)

If the patient has massive hematemesis, check his vital signs. If you detect signs of shock—such as tachypnea, hypotension, and tachycardia—place the patient in a supine position, and elevate his feet 20 to 30 degrees. Start a large-bore I.V. catheter for emergency fluid replacement. Also, obtain a blood sample for typing and crossmatching, hemoglobin level, and hematocrit, and administer oxygen. Emergency endoscopy may be necessary to locate the source of bleeding. Prepare to insert a nasogastric (NG) tube for suction or iced lavage. A Sengstaken-Blakemore tube may be used to compress esophageal varices. (See Managing hematemesis with intubation, page 356.)supraclavicular fossa, and neck. The patient may also show signs of respiratory distress, such as dyspnea and cyanosis.

obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic hepatic or renal failure, and chronic NSAID use all predispose elderly people to hemorrhage secondary to coexisting ulcerative disorders.

If the patient has severe hematochezia, check his vital signs. If you detect signs of shock, such as hypotension and tachycardia, place the patient in a supine position and elevate his feet 20 to 30 degrees. Prepare to administer oxygen, and start a large-bore I.V. catheter for emergency fluid replacement. Next, obtain a blood sample for typing and crossmatching, hemoglobin level, and hematocrit. Insert a nasogastric tube. Iced lavage may be indicated to control bleeding. Endoscopy may be necessary to detect the source of the bleeding.

If the patient has severe hematochezia, check his vital signs. If you detect signs of shock, such as hypotension and tachycardia, place the patient in a supine position and elevate his feet 20 to 30 degrees. Prepare to administer oxygen, and start a large-bore I.V. catheter for emergency fluid replacement. Next, obtain a blood sample for typing and crossmatching, hemoglobin level, and hematocrit. Insert a nasogastric tube. Iced lavage may be indicated to control bleeding. Endoscopy may be necessary to detect the source of the bleeding.in other body systems, producing such signs as epistaxis and purpura. Associated findings vary with the specific coagulation disorder.

bleeding. If the peptic ulcer penetrates an artery or vein, massive bleeding may precipitate signs of shock, such as hypotension and tachycardia. Other findings may include chills, fever, nausea and vomiting, and signs of dehydration, such as dry mucous membranes, poor skin turgor, and thirst. Most patients have a history of epigastric pain that’s relieved by foods or antacids; some also have a history of habitual use of tobacco, alcohol, or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree