Susan A. Carzo and Joseph H. Viveiros

Gynecologic and Obstetric Surgery

At some point in their lives, many women face the prospect of undergoing gynecologic surgery. Surgical procedures on structures of the female reproductive system are performed for diagnostic, therapeutic, or cosmetic purposes. Conditions requiring surgery include abnormal bleeding, benign or suspected malignant neoplasms, infertility, or the need to remove or repair weakened structures. A majority of surgical procedures carried out in the United States are performed on women (Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project [HCUPnet], 2009). With the resurgence of interest in issues and priorities related to women’s health (Berg et al, 2013), a holistic approach with sensitivity to the special needs of this population is an essential component of perioperative patient care.

Surgical Anatomy

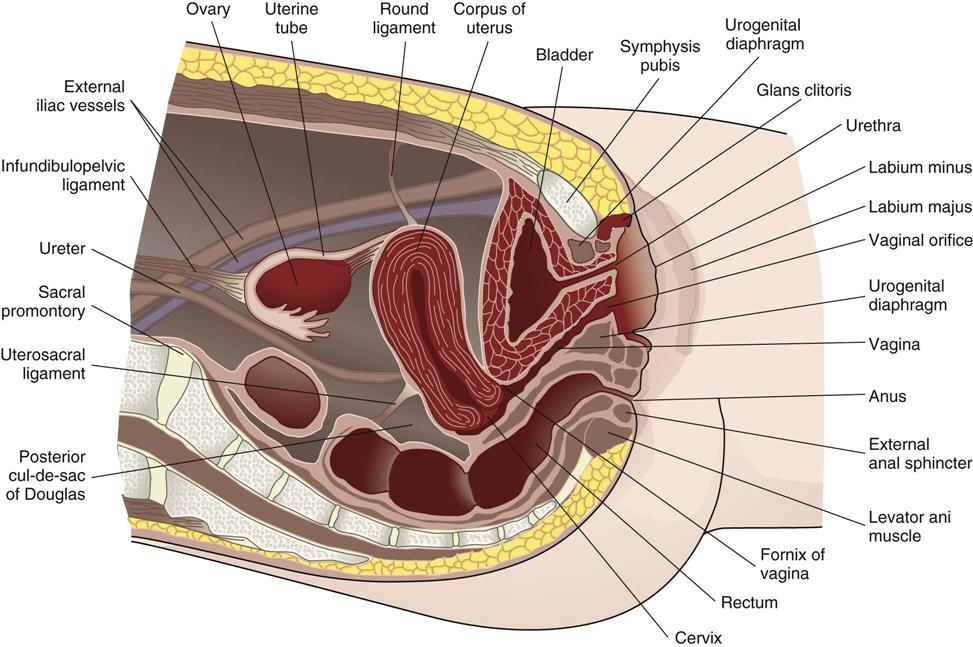

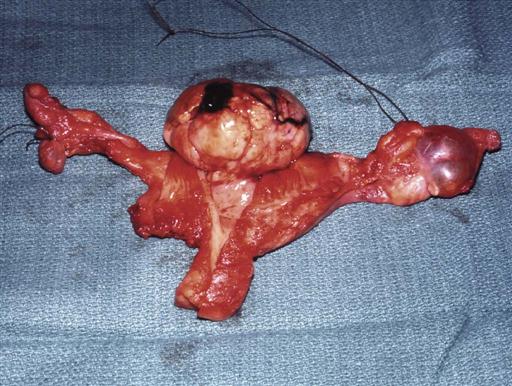

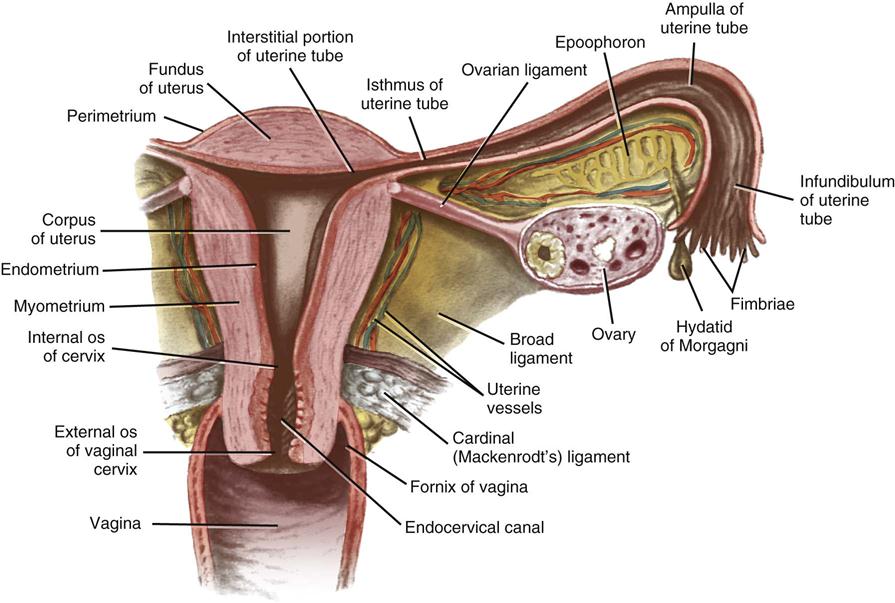

The female reproductive organs and their relationships are shown in Figures 14-1 and 14-2. The adult female structures associated with the process of reproduction are the external organs (vulva), the associated ligaments and muscles, the soft tissues and contents of the pelvic cavity, and the bony pelvis.

Female External Genital Organs (Vulva)

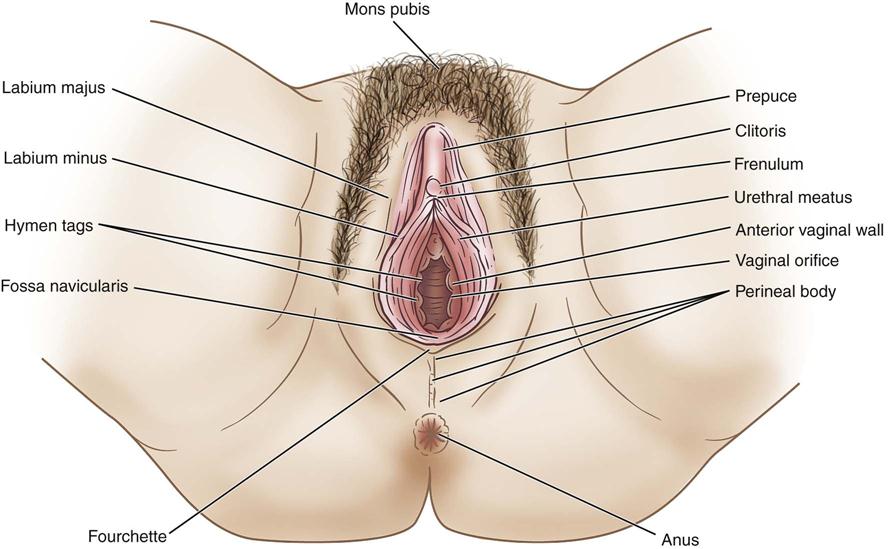

The external organs, referred to collectively as the vulva, include the mons pubis, the labia majora and labia minora, the clitoris, the vestibular glands, the vaginal vestibule, the vaginal opening, and the urethral opening (Figure 14-3).

The mons pubis is a mound of adipose tissue covered by skin and, after puberty, by hair as well. It is situated over the anterior surface of the symphysis pubis.

The labia majora are two folds of adipose tissue covered with skin that extend downward and backward from the mons pubis. Varying in appearance according to the amount of adipose tissue, they unite below and behind the mons pubis to form the posterior fourchette and in front of the mons pubis to form the anterior fourchette. The labia minora are the two hairless, flat, delicate folds of skin that lie within the labia majora. Each labium splits into lateral and medial parts. The lateral part forms the prepuce or hood of the clitoris and the medial part forms the frenulum. The posterior folds of the labia are united by a delicate fold extending between them, forming the fossa navicularis.

The clitoris is the homolog of the penis in the male. It hangs freely and terminates in a rounded glans (small, sensitive vascular body). Unlike the penis the clitoris does not contain the urethra. The vaginal vestibule is a smooth area surrounded by the labia minora, with the clitoris at its apex and the fossa navicularis at its base. It contains openings for the urethra and the vagina.

The urethra, which is about 4 cm long in premenopausal women, is close to the anterior vaginal wall and connects the bladder with the urethral meatus. Two small paraurethral ducts, which are commonly known as Skene ducts, lie on either side of the urethral meatus and drain Skene glands.

The vaginal opening lies below the urethral meatus. The hymen surrounds the virginal vaginal opening and may be circular, crescentic, or fimbriated. Its remnants after vaginal intercourse are the carunculae hymenales or hymeneal tags.

Bartholin glands and ducts are located on each side of the lower end of the vagina at the 5 and 7 o’clock positions. The narrow ducts open into the vaginal orifice on the inner aspects of the labia minora. The glands secrete mucus and can become infected or inflamed.

Pelvic Cavity

Uterus

The uterus is an inverted pear-shaped organ situated in the pelvic cavity between the bladder and the rectum. It gains much of its support from its direct attachment to the vagina and from indirect attachments to nearby structures, such as the rectum and pelvic diaphragm. The uterus is supported on each side by the broad, round, cardinal, and uterosacral ligaments and levator ani muscles (see Figures 14-1 and 14-2). The upper lateral points, the uterine cornua, receive the fallopian tubes. The fundus of the uterus is the upper, rounded portion positioned above the level of the tubal openings and just below the pelvic brim. Below, the body, or corpus, of the uterus joins the cervix. The corpus is separated from the cervix by a slight constriction (canal) called the isthmus. The cervix lies at the level of the ischial spines. The body of the uterus communicates with the cervical canal at the internal orifice, called the internal os. The constriction (endocervical canal) ends at the vaginal portion of the cervix at the external orifice, called the external os. The external os varies in appearance and is typically round and 2 to 3 mm in diameter in the nulliparous woman; after delivery, it may become oval, round, or wide and slitlike.

The uterine body has three layers: (1) the outer peritoneal, or serous, layer, which is a reflection of the pelvic peritoneum; (2) the myometrium, or muscular layer, which houses smooth muscle, nerves, blood vessels, and lymphatics; and (3) the endometrium, or mucosal layer, which lines the cavity of the uterus.

The ureters descend into the pelvis posteriorly at the level of the ovaries, after which they pass under the uterine arteries and run laterally along the base of the paracervcial ligament, where they connect to the posterior bladder, anterior to the vagina. Because of the proximity of the ureters to the female reproductive organs, it is important to identify and understand their anatomic relationship to other structures within the pelvic cavity during gynecologic surgical procedures.

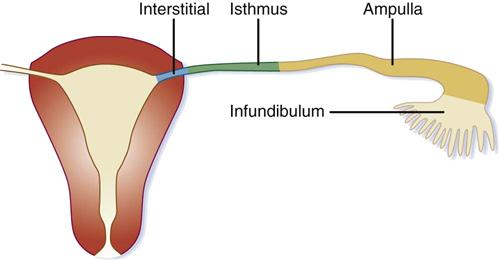

Fallopian Tubes (Oviducts)

The Greek word salpinx, meaning “trumpet” or “tube,” is used to refer to the fallopian tubes (Figure 14-4). The tubes are paired and consist of a musculomembranous channel about 10 to 13 cm long, forming the canals through which the ova are conveyed to the uterus from the ovaries. The outer surfaces of the tubes are covered by peritoneum. The inner layers are composed of muscular tissue lined with ciliated epithelium. Each tube receives its blood supply from the branches of the uterine and ovarian arteries and has four parts. (1) The infundibulum is trumpet shaped, opens into the abdominal cavity, and has finger-like projections called fimbriae. (2) The ampulla forms more than half of the tube and is thin walled and tortuous. (3) The isthmus is cylindric and forms approximately one third of the tube. (4) The remainder of the fallopian tube is known as both the intramural or interstitial portion. Measuring approximately 1 cm in length, it passes through the wall of the uterus.

It has been theorized that transfer of the ova from the ruptured follicles into the uterus is accomplished through vascular changes that occur during contraction of the smooth muscle fibers of the tube. The peristaltic action of the muscular layer and the ciliary movement propel the ova toward the uterus.

The right tube and ovary are in close relationship to the cecum and appendix; the left tube and ovary are situated near the sigmoid flexure.

Ovaries

The ovaries are located on each side of the uterus. The ovaries and tubes are collectively known as the adnexa. Each ovary lies within a depression (ovarian fossa) on the lateral wall of the pelvic cavity and above the broad ligament (see Figure 14-1). The anterior border of each ovary is attached to the posterior layer of the broad ligament by a peritoneal fold (mesovarium) and is suspended by the ovarian ligament.

The ovaries are small almond-shaped organs composed of an outer layer, known as the cortex, and an inner vascular layer, known as the medulla. The medulla consists of connective tissue containing nerves, blood vessels, and lymph vessels. The ovary is covered by epithelium, not peritoneum. The cortex contains ovarian (graafian) follicles in different stages of maturity. After ovulation the corpus luteum arises from the graafian follicle that expelled the ovum.

The ovaries produce ova after puberty and also function as endocrine glands, producing hormones such as estrogen, secreted by the ovarian follicles. Estrogen controls the development of secondary sexual characteristics and initiates growth of the lining of the uterus during the menstrual cycle. Progesterone, which is secreted by the corpus luteum, is essential for implantation of the fertilized ovum and for the development of the embryo.

Ligaments of the Uterus

The uterus has numerous ligaments to support its structure such as the broad, round, cardinal, and uterosacral ligaments (see Figures 14-1 and 14-2).

The pelvic peritoneum extends laterally, downward, and posteriorly from each side of the uterus. A double fold of pelvic peritoneum forms the layers of the broad ligament, enclosing the uterus. These layers separate, thereby covering the floor and sides of the pelvis. The fallopian tube is situated within the free border of the broad ligament. The free margin of the upper division of the broad ligament, lying immediately below the fallopian tube, is termed the mesosalpinx. Each ovary lies behind its respective broad ligament.

Round ligaments are fibromuscular bands attached to the uterus. Each round ligament passes forward and laterally between the layers of the broad ligament to enter the deep inguinal ring.

Cardinal ligaments (also known as paracervical or Mackenrodt ligaments) are composed of connective tissue with smooth muscle fibers and provide strong support for the uterus. They are found at the base of each of the broad ligaments and contain or house the uterine artery and vein.

Uterosacral ligaments are a posterior continuation of the peritoneal tissue. The ligaments pass posteriorly to the sacrum on either side of the rectum.

Vagina

The vagina is a rugated musculomembranous tube. It carries the menstrual blood from the uterus, serves as the organ for sexual intercourse, and is the terminal portion of the birth canal. The anterior wall measures 6 to 8 cm in length and the posterior wall 7 to 10 cm (see Figures 14-1 and 14-2). The anterior wall of the vagina is in proximity to the bladder and urethra. The lower posterior wall is anteriorly adjacent to the rectum. The upper portion of the vagina lies above the pelvic floor and is surrounded by visceral pelvic fascia. The lower half is surrounded by the levator ani muscles.

Cervix

The cervix consists of a supravaginal portion, which is closely associated with the bladder and the ureters, and a vaginal portion, which projects downward and backward into the vaginal vault. The projection of the cervix into the vaginal vault divides the vault into four regions, called fornices: anterior, posterior, right lateral, and left lateral.

The posterior fornix is in contact with the peritoneum of the pouch or cul-de-sac of Douglas. The rectovaginal septum lies between the vagina and rectum. The dense connective tissue separating the anterior wall of the vagina from the distal urethra is termed the urethrovaginal septum.

Bony Pelvis

The pelvis is the portion of the trunk below and behind the abdomen. The bony pelvis is composed of the ilium, symphysis pubis, ischium, sacrum, and coccyx. The so-called pelvic brim divides the abdominal false portion, located above the arcuate line, from the true portion of the pelvis, located below this line. The bony pelvis accommodates the growing fetus during pregnancy and the birth process.

The true pelvis is considered to have three parts: inlet, cavity, and outlet. The muscles lining the pelvis facilitate movement of the thighs, give form to the pelvic cavity, and provide a firm elastic lining to the bony pelvic framework. All organs located in the pelvis are covered by pelvic fascia, which is extremely important in maintaining the normal strength within the pelvic floor.

The fascia covering the muscles is usually dense and firm, whereas the fascia covering organs is often thin and elastic. The nerves, blood vessels, and ureters coursing through the anatomic structures of the pelvis are closely associated with muscular and fascial structures.

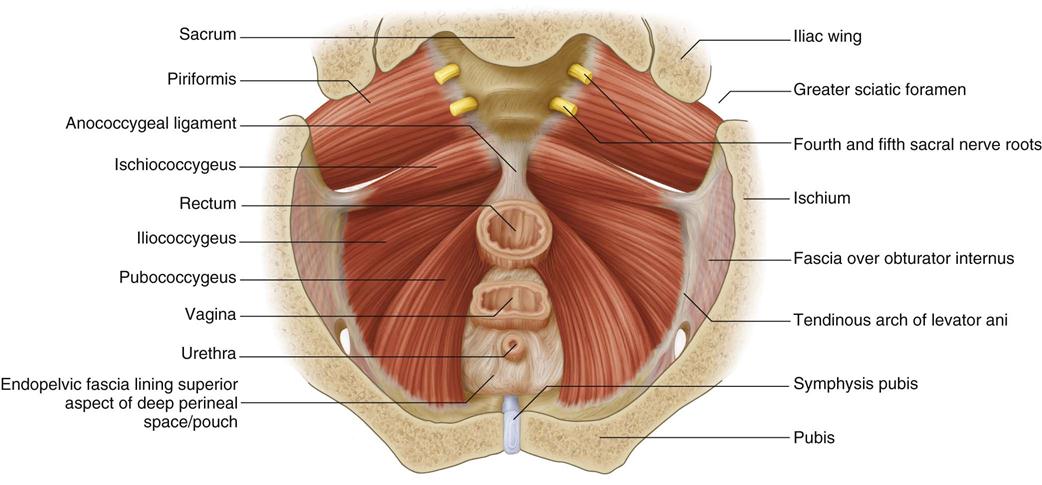

Pelvic Floor

The pelvic floor acts as a supportive sling for the pelvic contents (Figure 14-5). The pelvic fascia may be divided into three general groups: parietal, diaphragmatic, and visceral. The parietal pelvic fascia covers the muscles of the true pelvic wall and perineum. The diaphragmatic fascia covers both sides of the pelvic diaphragm, which is made up of the levator ani and coccygeal muscles. The visceral fascia is thin and flexible and covers the pelvic organs. The floor of the pelvis, known as the pelvic diaphragm, gives support to the abdominal pelvic viscera in this region. It consists of the levator ani and coccygeal muscles with their respective fascial coverings, separating the pelvic cavity from the perineum.

The levator ani muscles, varying in thickness and strength, may be divided into three parts: the iliococcygeal, the pubococcygeal, and the puborectal muscles. The fibers of the levator ani muscles blend with the muscle fibers of the rectum and vagina. The pubovaginal fibers of the pubococcygeal portion of the levator ani muscles, lying directly below the urinary bladder, are involved in the control of micturition. The pubococcygeal fibers of the levator ani muscles control and pull the coccyx forward and assist in the closure of the pelvic outlet. The fibers pull the rectum, vagina, and bladder neck upward toward the symphysis pubis in an effort to close the pelvic outlet and are responsible for the flexure at the anorectal junction. Relaxation of the fibers during defecation permits a straightening at this junction. During childbirth, the action of the levator ani muscles directs the fetal head into the lower part of the passageway.

Vascular, Nerve, and Lymphatic Supply of the Reproductive System

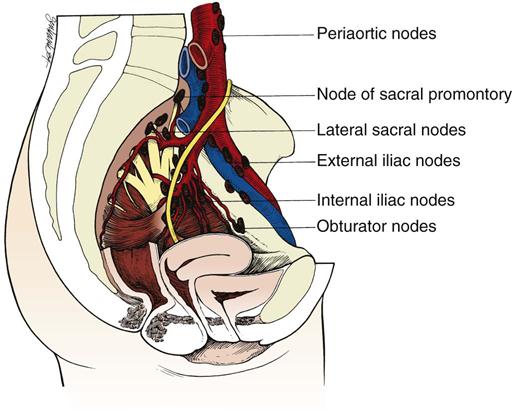

The blood supply of the female pelvis is derived from the internal iliac branches of the common iliac artery and is supplemented by the ovarian, superior rectal, and median sacral arteries, which are branches of the aorta.

The nerve supply of the female pelvis comes from the autonomic nerves that enter the pelvis in the superior hypogastric plexus (presacral nerve). The lymphatics of the female pelvis either follow the course of the vessels to the iliac and preaortic nodes or empty into the inguinal glands (Figure 14-6).

Perioperative Nursing Considerations

Assessment

Quality perioperative patient care depends on thorough nursing assessment and planning skills. Gynecologic patient information is gathered through nursing and physician interviews, evaluation of the patient’s systems, physical examination, collection of medical and surgical histories (Box 14-1), and thorough diagnostic testing. Family history of gynecologic disease, hypertension, diabetes, and heart disease are vital elements to consider when assessing and planning patient care.

Skillful interpersonal communication techniques are essential components to any nursing assessment. Patient interviews are conducted in ambulatory surgical centers, preoperative holding rooms, and on hospital patient care units. During this preoperative period the perioperative nurse provides support and patient education, and obtains information to help prepare for the surgical procedure and nursing plan of care (Goodman and Spry, 2014). Privacy is provided during the patient’s perioperative interview whenever possible, providing a safe environment for sharing information between patient and perioperative nurse. Questions concerning reproduction and gynecologic history may embarrass or be distressful for the patient. Personal values, native language, and cultural beliefs are all considered and respected during the interview process.

Throughout the assessment the perioperative nurse remains open, nonbiased, compassionate, and supportive to assist in establishing a trusting therapeutic relationship. Creating a trusting relationship also facilitates the nurse’s assessment for intimate partner violence (IPV). IPV is a major health concern worldwide (Shaver et al, 2013). A World Health Organization (WHO) multi-country study found 15% to 71% of women have reported an experience of IPV in their lifetime (WHO, 2011). The perioperative nurse must identify and understand the warning signs of IPV. The patient’s concerns for her own safety during the perioperative period and beyond are also addressed (Patient Safety).

The gynecologic patient’s history includes a chronologic listing of each pregnancy, length of gestation, type of delivery, complications during pregnancy, duration of labor, and fetal weight. Her menstrual cycle is discussed and data should include age at onset, length of cycle, amount of flow, duration of bleeding, and any pain or discomfort associated during her menses. The amount of flow is described in relation to number of pads and tampons used during her menstrual cycle. Onset of menopause is also documented when applicable. Additional considerations for the gynecologic assessment are noted in Box 14-1. See the laboratory values in Appendix A for common studies in the reproductive assessment of gynecologic patients.

Gynecologic disorders may be associated with urinary problems. The perioperative nurse inquires about stress incontinence or loss of urine while coughing, sneezing, exercising, or laughing. Getting up at night to urinate may reflect irritative changes in the bladder, shifting of extravascular fluids in the recumbent position, or decreased bladder capacity. Any urgency, pain or burning sensations during urination is also assessed.

A medication history includes the use of analgesics, oral contraceptives, estrogen therapy, diuretics, antihypertensives, cardiac medications, and use of herbal supplements or nutraceuticals. Herbal supplements can interfere with the patient’s ability to clot effectively during surgery (e.g., vitamins C and E and St. John’s wort) (see Chapter 30 for a thorough discussion of integrative therapies). It is essential to note the name, frequency, dose, and duration of all medications in the patient’s record during the perioperative assessment. The nurse continues the assessment by reviewing the physician’s history and physical examination, lab results, and results of any diagnostic studies. This knowledge assists with planning intraoperative care.

The gynecologic patient may undergo numerous preoperative diagnostic studies. The studies performed depend on the gynecologic problem or disease. Some studies performed as part of preoperative assessment include ultrasonography, computed tomography (CT) scanning, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Each of these studies contributes to the evaluation of patients suspected of having a malignancy and/or possible disease involvement of other surrounding organs. Vaginal and pelvic ultrasonography assists with diagnosing adnexal disease, endometrial hyperplasia, and uterine fibroids, as well as detecting blood or fluid within the pelvis.

Hysterosalpingograms or sonohysterograms are commonly performed in radiology and used to identify abnormalities in the uterine cavity or possible occlusions within the tubal folds. These diagnostic tools are most useful in detecting causes of infertility and identifying intrauterine masses that appear as endometrial thickening on routine ultrasound.

A colposcopy, with binocular magnification, is often performed in the surgeon’s office. Patients who have an abnormal Papanicolaou (Pap) smear suggestive of dysplasia undergo this examination. Colposcopy identifies cellular abnormalities involving the vulva, vagina, or cervix and helps to identify localized areas of dysplasia and carcinoma in situ. Endocervical curettage samples can be obtained during the colposcopic procedure to rule out invasive carcinoma or to detect early adenocarcinoma of the cervix.

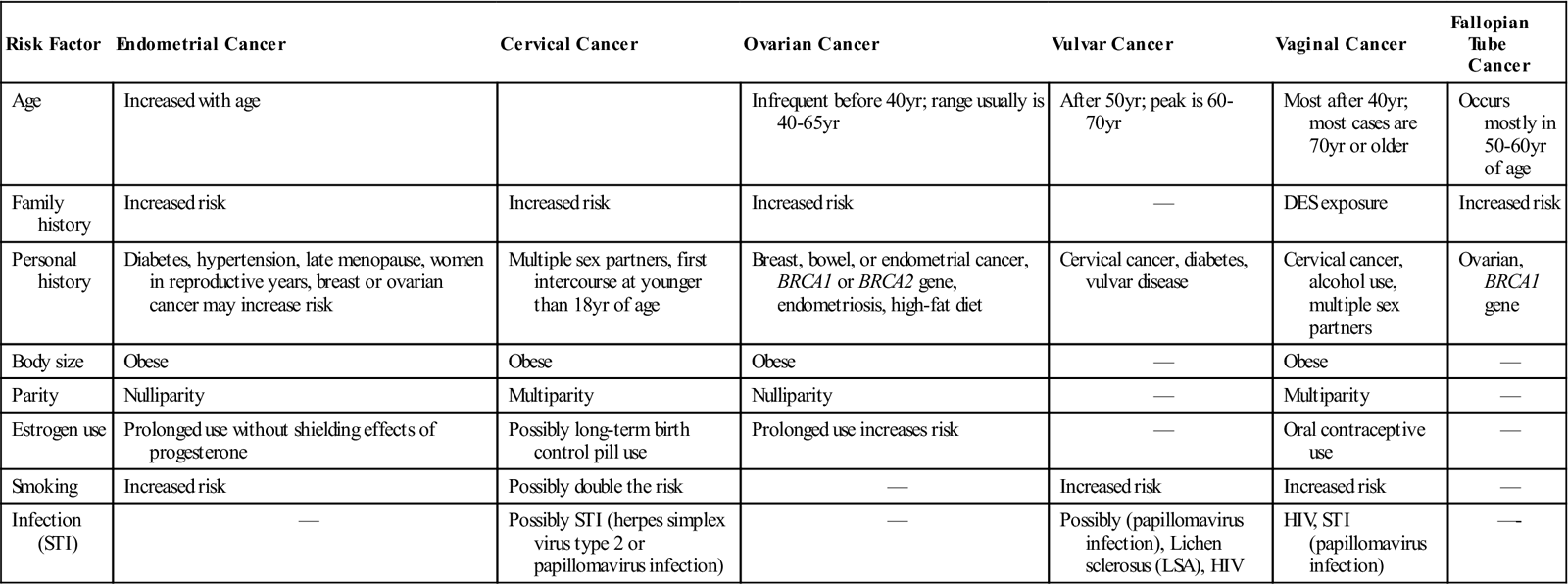

Gynecologic Carcinoma.

Gynecologic cancers commonly occur in the cervix, ovaries, vagina, and endometrial layer of the uterus. Less common sites for gynecologic carcinomas are the vulva and fallopian tubes. Some risk factors associated with gynecologic cancers are human papillomavirus (HPV) infection, inherited familial predisposition to cancer, such as Lynch syndrome (hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer [HNPCC]) and BRCA gene mutation carriers. Other risk factors linked with the development of these cancers are noted in Table 14-1.

TABLE 14-1

Risk Factors for Cancers of the Reproductive System

| Risk Factor | Endometrial Cancer | Cervical Cancer | Ovarian Cancer | Vulvar Cancer | Vaginal Cancer | Fallopian Tube Cancer |

| Age | Increased with age | Infrequent before 40 yr; range usually is 40-65 yr | After 50 yr; peak is 60-70 yr | Most after 40 yr; most cases are 70 yr or older | Occurs mostly in 50-60 yr of age | |

| Family history | Increased risk | Increased risk | Increased risk | — | DES exposure | Increased risk |

| Personal history | Diabetes, hypertension, late menopause, women in reproductive years, breast or ovarian cancer may increase risk | Multiple sex partners, first intercourse at younger than 18 yr of age | Breast, bowel, or endometrial cancer, BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene, endometriosis, high-fat diet | Cervical cancer, diabetes, vulvar disease | Cervical cancer, alcohol use, multiple sex partners | Ovarian, BRCA1 gene |

| Body size | Obese | Obese | Obese | — | Obese | — |

| Parity | Nulliparity | Multiparity | Nulliparity | — | Multiparity | — |

| Estrogen use | Prolonged use without shielding effects of progesterone | Possibly long-term birth control pill use | Prolonged use increases risk | — | Oral contraceptive use | — |

| Smoking | Increased risk | Possibly double the risk | — | Increased risk | Increased risk | — |

| Infection (STI) | — | Possibly STI (herpes simplex virus type 2 or papillomavirus infection) | — | Possibly (papillomavirus infection), Lichen sclerosus (LSA), HIV | HIV, STI (papillomavirus infection) | —- |

DES, Diethylstilbestrol; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; STI, sexually transmitted infection.

Modified from Ignatavicius DD, Workman ML: Diseases and disorders. In Ignatavicius DD, Workman ML, editors: Medical-surgical nursing: patient-centered collaborative care, ed 7, St Louis, 2013, Saunders; American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO): Fallopian tube cancer, Alexandria, VA, 2012, available at www.cancer.net/cancer-types/fallopian-tube-cancer/risk-factors-and-prevention. Accessed February 23, 2013; American Cancer Society (ACS): Vulvar cancer, Atlanta, 2012, The Society, available at www.cancer.org/cancer/vulvarcancer/detailedguide/vulvar-cancer-risk-factors. Accessed February 23, 2013.

Endometrial cancer (Figure 14-7) is responsible for the most new cases of gynecologic cancer per year in the United States. This includes uterine sarcomas, which account for approximately 2% of the total number of endometrial cancers. It is estimated 1 in 38 women will be diagnosed with endometrial cancer during their lifetime. Patients with this type of cancer may be asymptomatic or they may experience postmenopausal bleeding as their primary symptom. Most women diagnosed are older than 50 years of age (American Cancer Society [ACS], 2012).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree