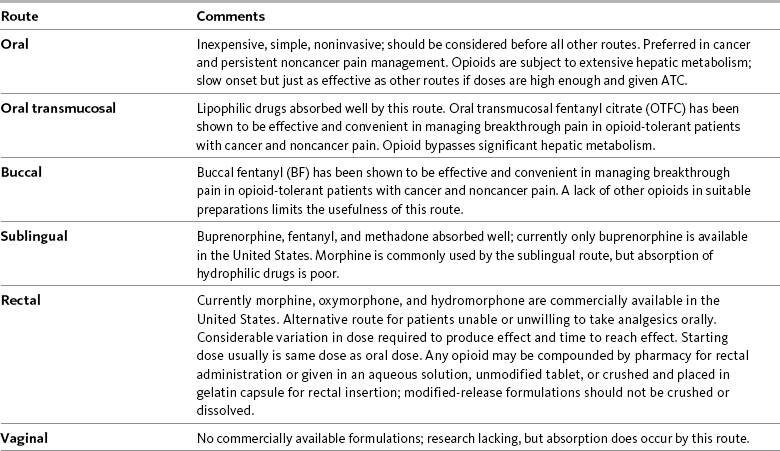

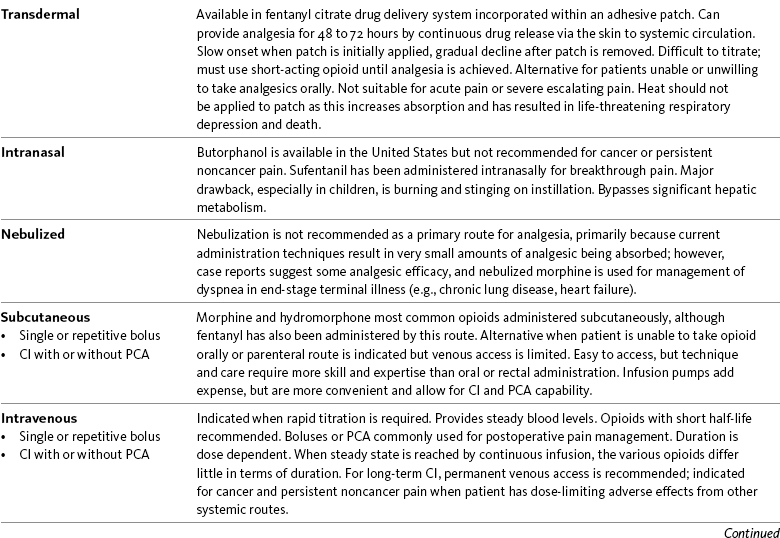

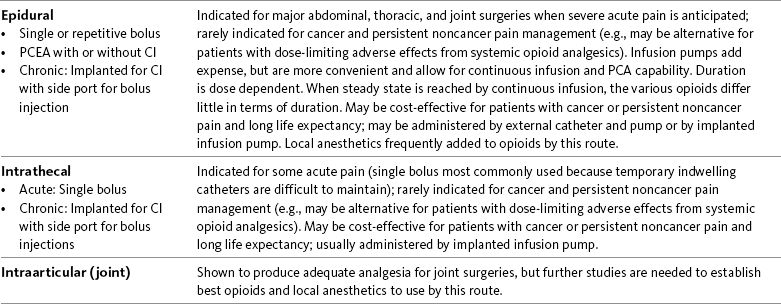

Chapter 14 Disadvantages of the Oral Route Selected Oral Opioid Formulations Trend in Oral Analgesics for Postoperative Pain Tamper-Resistant and Abuse-Deterrent Oral Opioid Formulations In a survey of patients with cancer pain, more than half required more than one route of administration to maintain pain control during the last 4 weeks of life. This occurred usually when patients were unable to swallow. The routes used included rectal, SC, IV, and epidural. Sometimes patients required more than one route at a time (Coyle, Adelhardt, Foley, et al., 1990). Table 14-1 summarizes the advantages and disadvantages to some of the routes of opioid administration. This chapter presents most of the routes by which opioids are administered. The intraspinal routes are discussed separately in Chapter 15. Table 14-1 Routes of Opioid Administration From Pasero, C., & McCaffery, M. (2011). Pain assessment and pharmacologic management, pp. 369-370, St. Louis, Mosby. Data from Buxton, I. L. O. (2006). Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. The dynamics of drug absorption, distribution, action, and elimination. In L. L. Brunton, J. S. Lazo, & K. L. Parker KL (Eds.), Goodman & Gilman’s the pharmacological basis of therapeutics, ed 11, New York, mcgraw-Hill; Darwish, M., Kirby, M., Jiang, J. G., et al. (2008). Bioequivalence following buccal and sublingual placement of fentanyl buccal tablet 400 microg in healthy subjects. Clin Drug Investig, 28(1), 1-7.; Darwish, M., Kirby, M., Robertson, P. Jr, et al. (2007). Absolute and relative bioavailability of fentanyl buccal tablet and oral transmucosal fentanyl citrate. J Clin Pharmacol, 47(3), 343-350; Dale, O., Hjortkjær, R., & Kharasch, E. D. (2002). Nasal administration of opioids for pain management in adults. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand, 46(7), 759-770; Gordon, D. B. (2008). New opioid formulations and delivery systems. Pain Manage Nurs, 8(3, Suppl 1), S6-S13; Gutstein, H. B., & Akil, H. (2006). Opioid analgesics. In L. L. Brunton, J. S. Lazo, & K. L. Parker (Eds.), Goodman & Gilman’s the pharmacological basis of therapeutics, ed 11, New York, mcgraw-Hill; Hanks, G., Cherny, N. I., & Fallon, M. (2004). Opioid analgesic therapy. In D. Doyle, G. Hanks, N. I. Cherny, et al. (Eds.), Oxford textbook of palliative medicine, ed 3, New York, Oxford Press; Holmquist, G. (2009). Opioid metabolism and effects of cytochrome P450. Pain Med, 10(Suppl 1), S20-S29; Shelley, K., & Paech, M. J. (2008). The clinical applications of intranasal opioids. Curr Drug Deliv, 5(1), 55-58; Smith, H. S. (2003). Drugs for pain. Philadelphia, Hanley & Belfus; Stevens, R. A., & Ghazi, S. M. (2000). Routes of opioid analgesic therapy in the management of cancer pain. www.medscape.com/viewarticle/408974. Accessed January 9, 2009; Swarm, R. A., Karanikolas, M., & Cousins, M. J. (2004). In D. Doyle, G. Hanks, N. I. Cherny, et al. (Eds.), Oxford textbook of palliative medicine, ed 3, New York, Oxford Press; Vascello, L., & McQuillan, R. J. (2006). Opioid analgesics and routes of administration. In O. A. de Leon-Casasola (Ed.), Cancer pain. Pharmacological, interventional and palliative care approaches, Philadelphia, Saunders. Pasero C, McCaffery M. May be duplicated for use in clinical practice. The oral route is not an option for patients who are NPO (nothing by mouth), such as immediately after surgery. Some patients cannot tolerate the oral route because of GI obstruction or difficulty swallowing (Fine, Portenoy, 2007). Absorption by the oral route can be altered by a number of factors, including presence of food, gastric emptying time, and GI motility. Modified-release preparations appear to be less affected by the presence of food than short-acting preparations (see individual drugs later in this chapter, and see Chapter 13 for more). Morphine is available in 15 and 30 mg short-acting tablets, and in 2, 4, 10, and 20 mg/mL solutions. These dose forms are used primarily when opioid therapy is initiated and for breakthrough pain (see Chapter 12 for more on breakthrough pain). MS Contin and Oramorph SR, modified-release formulations of morphine, are available in 15, 30, 60, and 100 mg tablets; MS Contin also is available in a 200 mg tablet. There are also generic products available at varying strengths. The recommended dosing interval is every 12 hours and no less than every 8 hours. There are two other modified-release morphine formulations, Kadian and Avinza, supplied as capsules that contain pellets which release drug at different rates. Kadian is available in 10, 20, 30, 50, 60, 80, 100, and 200 mg capsules and can be given every 12 or 24 hours. Avinza is available in 30, 45, 60, 75, 90, and 120 mg capsules and is approved for once-daily dosing. The Avinza prescribing information contains a black box warning that alcohol is not to be ingested while taking Avinza, as there is a risk of the pellets dissolving and the full daily dose of morphine being released at once (King Pharmaceuticals, 2008a). Kadian does not require such a warning (Alpharma Pharmaceuticals, 2008; Johnson, Wagner, Sun, et al., 2008), but alcohol can have additive CNS effects when ingested by a person taking any opioid and should be used with great caution. See Patient Education Form IV-9 (pp. 562-563) on short-acting morphine (includes concentrate), Form IV-10 (pp. 564-565) on modified-release 12-hour morphine, and Form IV-11 (pp. 566-567) on modified-release 24-hour morphine at the end of Section IV. Although the various forms of modified-release morphine contain the same drug and are of the same dose strength, they may or may not be bioequivalent. MS Contin and Oramorph SR, for example, are pharmaceutically equivalent because they contain the same drug, have the same dose form, can deliver the same amount of drug, are both available in the same dose strengths, and are given by the same route; however, the two are not necessarily therapeutically equivalent because they use different modified-release mechanisms. This means that the same dose of each product may not affect the patient in the same way (McCaffery, Lochman, 1996). The FDA does not consider any of the modified-release dose forms to be therapeutically equivalent unless bioequivalence data have been submitted. Given the many choices now available, it is best not to assume that very similar products will behave the same in a given individual. It should be recognized, however, that the FDA and some state laws have allowed pharmacists, physicians and other prescribers, institutions, and health care plans to consider drugs containing the molecule to be therapeutically equivalent, even in the absence of confirmatory clinical data. If patients report a change in the outcomes associated with stable drug therapy, the clinician should assess whether the formulation may have been changed by the pharmacist (McCaffery, Lochman, 1996). Box 14-1 provides recommendations when switching from one pharmaceutically equivalent product to another. Oxycodone is used extensively by the oral route and is available in both short-acting and modified-release formulations. It is also available alone or in combination (2.5 to 10 mg) with varying amounts of acetaminophen, aspirin, or ibuprofen (see Table 13-9 on p. 351). Single-entity oxycodone is available in 5, 15, and 30 mg tablets (capsules in 5 mg) and in two solution strengths, 5 mg/5mL and a 20 mg/mL concentrate (see the safety considerations for liquid opioids earlier in the chapter). The short-acting dose forms typically are used for short-term acute pain and for breakthrough pain. A drawback to the use of oxycodone combinations is that the clinician must carefully monitor the dose of acetaminophen, aspirin, or ibuprofen to ensure that maximum safe levels are not exceeded. Increases in the dose of oxycodone for inadequate pain relief are limited by acetaminophen’s and aspirin’s recommended maximum daily dose of 4000 mg and ibuprofen’s limit of 3200 mg (see Section III). At the time of publication, the United States Food and Drug Administration (U.S. FDA) was considering the need to restrict the availability of a maximum dose/tablet of acetaminophen to 325 mg and eliminate analgesics with fixed combinations of opioids-nonopioids (e.g., oxycodone plus acetaminophen [Percocet, Vicodin]) because of concerns of overdose and resultant liver failure (U.S. FDA, 2009b; Harris, 2008). Single-entity preparations have allowed broader use of oxycodone. Oxycodone is one of four opioid analgesics that are available in the United States in 12-hour modified-release form (OxyContin) for twice daily dosing; it is also approved for 8-hour dosing for patients who do not maintain pain relief for 12 hours (see Tamper-Resistant and Abuse-Deferrent Oral Opioid Formations on p. 378). OxyContin is available in 10, 15, 20, 30, 40, 60, 80, and 160 mg tablets. Doses of 60, 80 and 160 mg or any single dose of greater than 40 mg are approved for opioid-tolerant patients only. These are small tablets that are color-coded according to dose. See Patient Education Form IV-14 (pp. 572-573) on oxycodone with acetaminophen, Form IV-12 (pp. 568-569) on short-acting oxycodone, and Form IV-13 (pp. 570-571) on modified-release oxycodone at the end of Section IV. • Acute postoperative pain (Blumenthal, Min, Marquardt, et al., 2007; Cheville, Chen, Oster, et al., 2001; de Beer, Winemaker, Donnelly, et al., 2005; Dorr, Raya, Long, et al., 2008; Ginsberg, Sinatra, Adler, et al., 2003; Kampe, Warm, Kaufmann, et al., 2004) (See also Trend in Oral Analgesics for Postoperative Pain in paragraphs that follow.) • Cancer pain (Gralow, 2002; Pan, Zhang, Zhang, et al., 2007; Reid, Martin, Sterne, et al., 2006). • Persistent noncancer pain (Portenoy, Farrar, Backonja, et al., 2007; Roth, Fleischmann, Burch, et al., 2000) • Acute exacerbation of noncancer pain (Ma, Jiang, Zhou, et al., 2008) • Neuropathic pain (Eisenberg, McNicol, Carr, 2006; Furlan, Sandoval, Mailis-Gagnon, et al., 2006; Gimbel, Richards, Portenoy, 2003; Watson, Moulin, Watt-Watson, et al., 2003). Modified-release oxymorphone (Opana ER) was approved for use in the United States in 2006 for the treatment of moderate to severe persistent pain. Its unique formulation allows the release of oxymorphone dependent on the rate of penetration of water into a hydrophilic matrix. Modified-release oxymorphone is dosed every 12 hours, and, like short-acting oxymorphone, steady state is reached after 3 days of every-12-hour dosing (Smith, 2009). As mentioned, oxymorphone is more potent than oxycodone. One study explored the dose equivalency of modified-release formulations of oxymorphone and oxycodone and established an equianalgesic dose ratio of 2:1 (oxymorphone was twice as potent as oxycodone) (Gabrail, Dvergsten, Ahdieh, 2004). See Patient Education Form IV-15 (pp. 574-575) on short-acting oxymorphone and Form IV-16 (pp. 576-577) on modified-release oxymorphone at the end of Section IV. Modified-release oxymorphone has been found to be effective in the treatment of a variety of types of persistent cancer and noncancer pain (Brennan, 2009; Prager, Rauk, 2004; Sloan, Barkin, 2008; Sloan, Slatkin, Ahdieh, 2005; Slatkin, Tormo, Ahdieh, 2004). One study that evaluated modified-release oxymorphone in patients with persistent low back pain found that positive effects were less profound for those aspects of the pain likely to be neuropathic in origin (and described as cold, itchy, sensitive, tingling, and numb) than pains that were inferred to be nociceptive (and were described as sharp, aching, and deep) (Gould, Jensen, Victor, et al., 2009). This study lends support to the conclusion that is applied to all opioid drugs, i.e., that opioids are effective for neuropathic pain but may be relatively less effective for some pains of this type than pains conventionally considered to be nociceptive. (See Section I for more on nociceptive pain and neuropathic pain.) • Cancer pain (Sloan, Slatkin, Ahdieh, 2005; Gabrail, Dvergsten, Ahdieh, 2004) • Persistent low back pain (Gould, Jensen, Victor, et al., 2009; Hale, Ahdieh, Ma, et al., 2007; Hale, Dvergsten, Gimbel, 2005; Katz, Rauck, Ahdieh, et al., 2007; Penniston, Gould, 2009; Rauck, Ma, Kerwin, et al., 2008) • OA pain (Kivitz, Ma, Ahdieh, et al., 2006; Matsumoto, Babul, Ahdieh, 2005; McIlwain, Ahdieh 2005; Rauck, Ma, Kerwin, et al., 2008) Although further research in special populations is needed, plasma concentrations of the drug and its metabolites have been shown to be 40% (mean) higher in older adults; therefore, initial low doses should be used in these patients, and titration should proceed cautiously (Smith, 2009). As with short-acting oxymorphone, Guay (2007) recommends beginning with the lowest dose of modified-release oxymorphone, 5 mg every 12 hours. Dose adjustments of oxymorphone are also likely to be necessary in patients with moderate renal and hepatic disease (Smith, 2009). Guay (2007) recommends avoiding oxymorphone entirely in patients with moderate to severe hepatic impairment. The drug was shown in one study to be removed by hemodialysis (Smith, 2009). There appears to be a low risk for interaction with concurrent medications that are metabolized by the CYP450 enzyme system, which may be a significant benefit in patients who are poor metabolizers or those who take multiple medications that rely on this enzyme system for metabolism, such as some antidepressants, beta blockers, antipsychotics, chemotherapeutic agents, and some other opioids (Adams, Pieniaszek, Gammaitoni, et al., 2005; Chamberlin, Cottle, Neville, 2007; McIlwain, Ahdieh 2005; Smith, 2009) (see Chapter 11 for more on cytochrome P450 enzymes and drug-drug interactions). The reader is referred to a 2009 journal supplement devoted to content on oxymorphone: Pain Med 10(Suppl 1). A study of opioid-tolerant patients with persistent cancer pain (N = 73) or persistent noncancer pain (N = 331) stabilized the patients on their previous opioid, converted this dose to modified-release hydromorphone, then titrated to optimal dose using a stepwise approach, which was then maintained for 2 weeks (Palangio, Northfelt, Portenoy, et al., 2002). The majority of patients reached a stable dose of modified-release hydromorphone quickly (mean 12.1 days), and most required no or few steps to achieve it. The most common adverse effects were nausea and constipation. A morphine to hydromorphone conversion ratio of 5:1 was used, but the researchers reinforced the principle of decreasing the equianalgesic dose of the new opioid by 25% to 50% until research establishes differently (see Chapter 18). This study also suggested that direct conversion from another opioid to modified-release hydromorphone could be done without the intermediate step of titration with short-acting hydromorphone first. In other clinical trials, the once-daily hydromorphone has also been well tolerated with an adverse effect profile similar to other short- and modified-release opioid analgesics, such as morphine and oxycodone (Cousins, 2007; Gardner-Nix, Mercadante, 2010; Gupta, Sathyan, 2007; Hale, Tudor, Khanna, et al., 2007; Hanna, Thipphawong, 118 Study Group, 2008; Wallace, Thipphawong, 2007; Wirz, Wartenberg, Elsen, et al., 2006). Sublingual oxycodone and hydromorphone have been studied to a very limited degree (Reisfield, Wilson, 2007). An alkalinized oxycodone sublingual spray had a bioavailability of 70% in an animal model. Hydromorphone in healthy volunteers had a bioavailability of only 25%. The injectable forms of sufentanil and alfentanil have been used sublingually for breakthrough pain, but have not been studied (Gardner-Nix, 2001a; Hanks, Cherny, Fallon, 2004); with their high lipophilicity and potency (which exceeds fentanyl), they are a good theoretical choice, but the lack of commercially available products makes them impractical (Reisfield, Wilson, 2007). Fentanyl and methadone are well absorbed sublingually, but no preparations are commercially available (see the following discussion on oral transmucosal fentanyl) (Hanks, Cherny, Fallon, 2004); a sublingual fentanyl tablet now is available in some countries (Lennernas, Hedner, Holmberg, et al., 2005). A sublingual buprenorphine wafer has been approved for use in treatment of opioid addiction (Heit, Gourlay, 2008). A buprenorphine liquid product is available in other countries and may provide relief of mild to moderate pain. Sublingual buprenorphine absorption occurs within 3 to 5 minutes, bioavailability is 51%, and peak plasma concentrations generally occur at approximately 60 minutes (Johnson, Fudala, Payne, 2005). Breakthrough pain (sometimes called pain flare, episodic pain, or transient pain) is defined as a transitory exacerbation of pain in a patient who has relatively stable and adequately controlled baseline pain (Portenoy, Forbes, Lussier, et al., 2004) (see Chapter 12 for a detailed discussion of breakthrough pain). The ideal medication for breakthrough pain has been described as one with a fast onset, relatively short duration of action, and minimal adverse effects (Zeppetella, 2008). Transmucosal delivery of a lipophilic and potent drug such as fentanyl meets these characteristics. Fentanyl had been incorporated into three products approved in the United States for the treatment of breakthrough cancer pain at the time of publication; numerous others are in development. Although indicated for cancer-related breakthrough pain, these products are widely used for breakthrough pain in noncancer pain syndromes as well (Prime Therapeutics, 2007). Oral transmucosal fentanyl citrate (OTFC, Actiq®) is provided as a solid matrix or lozenge on a plastic stick (Figure 14-1, A). The medication is intended to be dissolved by saliva and absorbed through all oral mucosal surfaces. An effervescent fentanyl buccal tablet (FBT, Fentora®) is designed for placement against the buccal mucosa—between the upper gum and cheek—until it is dissolved (Figure 14-1, B). The newest formulation, BEMA (BioErodible MucoAdhesive; Onsolis) is a microadhesive polymer disk, about the size of a nickel, that contains fentanyl and is designed to stick to the oral mucosa (inside of the cheek) and dissolve within 15 to 30 minutes (Blum, Breithaupt, Hackett, et al., 2008). Figure 14-1 A, Oral transmucosal fentanyl citrate (OTFC). B, Fentanyl buccal tablet (FTB). Cephalon, Inc. OTFC is available in 200, 400, 600, 800, 1200, and 1600 mcg strengths (Cephalon, 2007). Individual titration, usually beginning with the lowest dose (200 mcg), is necessary. Dose adjustment on the basis of age alone is not required (Kharasch, Hoffer, Whittington, 2004), although elimination in older adults is prolonged (Gordon, 2006). To administer OTFC, the patient is instructed to hold onto the stick and place the lozenge between the gum and cheek. The stick is used to move and twirl the lozenge around the oral mucosa, particularly between the gums and cheek and above and below the tongue, so that it dissolves in the saliva. Patients should be told not to suck on the lozenge as one would suck on a candy lollipop; this will result in much of the drug being swallowed (oral route), negating the benefits of exposure to direct systemic circulation that the oral transmucosal route offers. Further, clinicians should not refer to OTFC as a lollipop, sucker, or popsicle, as this is not only misleading but can result in family members, particularly children in the home, misunderstanding that this is a medication (not candy) that should be consumed by the patient only. Biting or chewing will cause a greater proportion to be swallowed, also resulting in decreased effectiveness. It has been suggested that the patient swish the fentanyl-containing saliva around the mouth prior to swallowing to enhance oral mucosal absorption (Gordon, 2006). If pain relief is insufficient after 15 to 25 minutes and the entire lozenge has been consumed, a second lozenge may be used; there are no published data about the use of more than two lozenges successively, and this is not recommended (Cephalon, 2007) (see Box 14-2 for complete dosing recommendations). See Patient Education Form IV-4 (pp. 551-552) on oral transmucosal fentanyl at the end of Section IV.

Guidelines for Selection of Routes of Opioid Administration

Oral

Disadvantages of the Oral Route

Selected Oral Opioid Formulations

Oral Morphine

Oral Oxycodone

Oral Oxymorphone

Oral Hydromorphone

Oral Transmucosal

Sublingual

Oral Transmucosal Fentanyl for Breakthrough Pain

Guidelines for Selection of Routes of Opioid Administration