http://evolve.elsevier.com/Edmunds/NP/

Pharmacologic management of gout relies on the use of NSAIDs (see Chapter 36), colchicine, uricosuric agents (probenecid), and xanthine oxidase inhibitors (allopurinol and febuxostat) (Table 38-1).

TABLE 38-1

Pharmacologic Management of Different Phases of Gout

Modified from Schlesinger N: Management of acute and chronic gouty arthritis: present state-of-the art, Drugs 64(21):2399-2416, 2004; Morgan L: Colchicine in acute gout, Aust Fam Physician 37(3):103, 2008.

Therapeutic Overview

Gout is a term that is used to describe a collection of disorders caused by the deposition of monosodium urate crystals in body tissue. The condition has become increasingly more common in the United States in the past 2 decades, in part because of the nation’s obesity crisis and a greater frequency of high blood pressure. Gout can be classified as primary or secondary. Primary gout, which affects males 10 times more often than females, is caused by an inborn error of purine metabolism that results in the overproduction or underexcretion of uric acid. Secondary gout is associated with hyperuricemia that results from other diseases or drugs that interfere with uric acid secretion. Secondary gout arises from a multitude of causes, including endocrine disorders, lead poisoning, high-dose salicylates (more than 3 g/day), myeloproliferative disorders, and chronic renal disease. Obese patients seem to have earlier onset of gout.

The basic pathology of gout generally is classified into one of two categories: overproduction or underexcretion of uric acid. A 24-hour urine collection is used to differentiate overproducers from underexcreters of uric acid.

Disease Process

Four phases generally are recognized in the development of gout. The first is asymptomatic hyperuricemia, which, as the name implies, is not associated with any clinical symptoms. Evidence suggests that the higher an individual’s serum uric acid level, the greater is the likelihood that acute gout will develop. Acute gouty arthritis, the next phase, typically presents as a sudden, exquisitely painful monoarthropathy. Although any synovial joint can be affected, the most common site for this painful manifestation is the metatarsophalangeal joint of the great toe. The third phase, the intercritical period, is the period between acute attacks. Most individuals who develop gout have a second episode of gout within 6 months to 2 years of the first attack. Untreated gout tends to result in more frequent, severe attacks of longer duration. However, some patients will never have a second attack. Finally, chronic tophaceous gout can occur. Tophi are sodium urate crystals that are deposited in the soft tissues and can occur in up to 50% of patients with gout. They tend to appear at any time from 2 or 3 years to 10 years after the onset of gout. The most common locations for tophi are synovium, prepatellar and olecranon bursae, the Achilles tendon, and the helix of the ear.

Hyperuricemia, defined as serum urate level >6 mg/dl in men and >7 mg/dl in women, is the strongest risk factor for development of gout. The higher the serum urate level, the greater is the incidence of acute gouty arthritis. Hyperuricemia alone, however, is not diagnostic. Studies involving acute gout attacks have found that uric acid levels have been low to normal in 12% to 43% of patients. Key risk factors for gout include hypertension, thiazide and loop diuretics, obesity, and alcoholism. These risk factors seem to be additive in terms of risk. Other risk factors for developing gout include age older than 60, family history, lead exposure (patients who consume “moonshine” whiskey have an even greater risk because moonshine tends to have a high lead content), and the use of other medications (e.g., low-dose aspirin [<2 g/day], cyclosporine, tacrolimus, ethambutol, pyrazinamide, nicotinic acid). Dietary intake of meat and seafood has been shown to significantly increase the risk that a gout attack will occur; consumption of dairy products is associated with the lowest risk of attacks. Excessive alcohol consumption—specifically beer and spirits, but not wine—is associated with increased risk of an attack. Conditions such as thyroid problems, kidney disease, anemia, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, vascular disease, trauma, surgery, and radiation treatment also may serve as triggers for gout.

Up to 90% of individuals with gout are underexcreters of uric acid. Normally, the kidneys turn over approximately 700 mg/dl of uric acid per day. Of that amount, about 10% is excreted. Normal serum uric acid in males ranges from 2 to 7 mg/dl; the normal range for females is 2 to 6 mg/dl. Any factor that interferes with the glomerular and renal tubular reabsorption of uric acid can result in elevated serum uric acid levels.

Overproduction of uric acid is much less common. It is often the result of another disease, frequently one associated with excessive rates of cell turnover. Hemolytic anemias, myeloproliferative and lymphoproliferative diseases, and psoriasis are examples of processes that may cause secondary gout resulting from overproduction of uric acid. Some inherited diseases and genetic abnormalities can cause primary gout through overexcretion of uric acid.

The most important differential diagnosis to be made in a patient with gout is the exclusion of a septic joint. Synovial fluid aspiration and examination help confirm the diagnosis. Fluid is sent for WBC and differential, crystal analysis, and Gram stain with culture. Examination of joint fluid with the use of a polarized microscope will reveal the presence of crystals. The presence of birefringent crystals in the synovial fluid does not exclude the possibility of infection because gout and infection can coexist in a joint.

Mechanism of Action

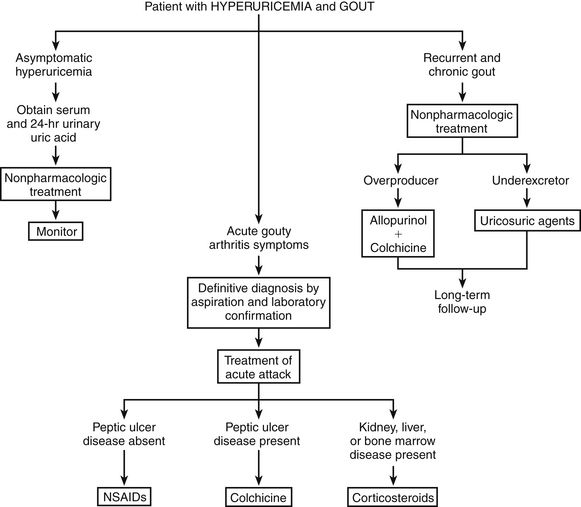

Use the following three mechanisms in the treatment of gout (Figure 38-1):

FIGURE 38-1 Suggested treatment algorithm for gout. (Modified from Gall EP: Hyperuricemia and gout. In Greene HL II et al, editors: Decision-making in medicine, ed 4, St Louis, 2007, Mosby.)

NSAIDs inhibit prostaglandin synthesis, thereby reducing the intensity of inflammation and pain in injured tissue. See Chapter 34 for a detailed discussion of prostaglandin inhibition.

The exact mechanism of action of colchicine is unknown. Colchicine affects leukocyte function to reduce lactic acid production. This results in decreased deposition of uric acid and reduction of the inflammatory response. Colchicine has no effect on uric acid metabolism and is not an analgesic.

Uricosuric agents (probenecid) are tubular blocking agents. They decrease serum uric acid levels by increasing urinary excretion of uric acid caused by inhibition of tubular reabsorption of urate. During this process, high concentrations of uric acid develop in the proximal renal tubules. This may predispose the patient to the development of urinary stones. For this reason, increased fluid intake is necessary and alkalinization of the urine is desirable when uricosuric therapy is initiated. Probenecid also inhibits the tubular secretion of most penicillins and cephalosporins. This increases the effectiveness of antibiotics.

Allopurinol and febuxostat inhibit xanthine oxidase, the enzyme that converts xanthine to uric acid. This reduces uric acid production by altering the breakdown of purines to produce xanthines rather than urates. Xanthines are much more soluble than uric acid and therefore have a much greater renal clearance. Different from uricosuric agents, allopurinol xanthine oxidase inhibitors do not promote uric acid secretion, so the level of uric acid in the renal tubules is not increased.

Treatment Principles

Evidence-Based Recommendations

No firm evidence-based guidelines have been put forth regarding when in the course of gout it is most appropriate to start urate-lowering therapy. This is essentially up to the patient and the clinician.

Cardinal Points of Treatment

Asymptomatic Hyperuricemia

Although the treatment of asymptomatic patients is somewhat controversial, a blood uric acid level greater than 7 mg/dl may warrant treatment if the patient has multiple other risk factors. However, most clinicians recommend that asymptomatic hyperuricemia not be treated.

Nonpharmacologic management of asymptomatic gout is generally attempted. Adequate fluid intake is necessary. Preventive measures include managed weight loss, primary prevention of hypertension, decreased alcohol consumption, and dietary modifications to reduce purine intake. A low-purine diet restricts the consumption of meat and prohibits alcohol, liver, kidney, sweetbreads, dried beans and peas, mushrooms, lentils, spinach, anchovies, sardines, and whole-grain and bran breads and cereals.

Acute Gouty Arthritis

The goal of therapy is to decrease or stop the inflammatory response. Treatment of acute gout usually begins with NSAIDs; pharmacologic treatment of hyperuricemia must be started after the acute attack has subsided. Initiate treatment immediately, and put the patient on bed rest for the first 24 hours.

NSAIDs are the drugs of choice for reducing the inflammation and pain of acute gout. NSAIDs indicated for gout include indomethacin, naproxen, and sulindac, but all NSAIDs are somewhat effective. Indomethacin traditionally has been used most frequently; however, it is associated with a high risk of adverse effects, and the newer NSAIDs are considered equipotent. If the patient is at high risk for GI bleeding, a COX-2 inhibitor may be appropriate.

Colchicine is used for the acute attack, but it is no longer recommended as first-line treatment because of the nausea and vomiting that often occur prior to the relief of pain. Corticosteroids are very effective but should be reserved for patients who are unable to take NSAIDs or colchicine. Corticosteroids are given by intraarticular injection if the gout is monoarticular. Opioids are used to treat severe pain, if required. A new interleukin-1 trap drug, rilonacept, has also been used to control the pain of an acute gouty attack, but little information about it is available to date.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Key drug. Drugs are listed in approximate order of use.

Key drug. Drugs are listed in approximate order of use.