- What are the global burdens of disease and how they differ between low-middle income and high income countries?

- What are the wider determinants of health and the potential impact of demographic changes, migration and globalisation?

- What is the role for global initiatives to address these problems and

- What are the possible solutions to improve global health?

What is global health?

Global health can be defined as

health problems, issues and concerns that transcend national boundaries, may be influenced by circumstances or experiences in other countries, and are best addressed by cooperative actions and solutions.

(US Institute of Medicine, 2008)

Alternatively, and more comprehensively, global health is ‘an area for study, research, and practice that places a priority on improving health and achieving equity in health for all people worldwide’ (Koplan et al., 2009).

Some examples are: avian flu; tobacco control; climate change to mention just a few.

Global health relies on people from a range of different disciplines, often outside of conventional health sciences, working together. Global health is exciting because it requires new thinking and there are no ‘textbook’ solutions. Most situations require different mixes of skills, there are different stakeholders, and different means of understanding and formulating problems – and sometimes solving them.

Global burden of death and disability

Reliable information on causes of death is essential to development of national and international policies for prevention and control of disease and injuries. However, data collection is often limited in many developing countries; medically certified information is available for less than a third of deaths worldwide.

The Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study, supported by the World Bank and the World Health Organisation (WHO), used various data sources and techniques to estimate the numbers of deaths and disability adjusted life years (DALYs); numbers of years of life lost due to ill-health, disability or early death) attributable to specific causes.

Of the 56 million deaths worldwide in 2001, a third were from communicable, maternal, and perinatal conditions and nutritional deficiencies, while non-communicable diseases were the commonest causes of death worldwide (Table 22.1). Of these deaths, 10.6 million were children, 99% of whom lived in low- and middle-income countries.

Table 22.1 Ten leading causes of death by income group.

Factors that influence research and public health action are:

Communicable diseases

Communicable diseases continue to take a heavy toll in developing countries: approximately half of all deaths in the least developed countries are estimated to result from communicable diseases, of which approximately 90% are attributed to: acute diarrhoeal and respiratory infections of children, AIDS, tuberculosis, malaria and measles.

These communicable diseases pose a great challenge because (a) lack of effective vaccines (except for measles), (b) those at risk or already infected are unable to access medicines and other goods such as bed-nets and condoms. The reasons for these include costs of health goods, as well as the lack of health systems capable of getting these goods to those at risk or in need.

The so-called neglected tropical diseases – such as leprosy, lymphatic filariasis, and onchocerciasis – continue to cause a great deal of human suffering and permanent disability, as well as being an economic burden on the individual (unable to join the workforce) and their families and society upon which they must often depend for economic support.

Economic consequences of these conditions are still not adequately appreciated by governments; tuberculosis alone causes an estimated annual loss of between US$ 1.4 and 2.8 billion in economic growth worldwide.

In addition to these endemic infections, there are often unpredictable infections such as rare outbreak-prone disease (Ebola, Marburg) to cholera, and seasonal or pandemic influenza. Not only do these diseases cause human suffering and death, often placing health workers at great risk, but they cause negative economic impact from control measures such as culling of livestock and animals from which many of these infections originate. Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy (BSE), and the associated new human variant of Creutzfeld Jakob Disease (vCJD), cost the UK economy around £1.5bn during 1996/97; and the Food and Agricultural Organisation (FAO) estimates that H5N1 has cost South-East Asia’s poultry farmers approximately $10 billion from 2003 to 2007 – strong reminders of the negative economic impact caused by emerging infectious diseases.

The power of vaccines in decreasing disease and death was clearly demonstrated by the eradication of smallpox, a major infectious cause of death.

In 1967 (the year that intensive efforts to eradicate smallpox began) there were an estimated 2.7 million smallpox deaths. In 1980 smallpox was certified eradicated.

Vaccines have had a major impact on polio, in the last phase of a global eradication programme, measles, tetanus, diphtheria and pertussis. Newer vaccines such as those for hepatitis B, haemophilus B (Hib), human papillomavirus (HPV) and rotavirus show great promise – once they have been successfully integrated into routine immunisation programmes in all countries – both in preventing acute illness, and chronic disease including hepatic and cervical cancers. Access to vaccines and other health goods has been facilitated by UNICEF and mechanisms for donor funding such as Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunizations (GAVI) and the Global Fund on AIDS, TB, and Malaria. However, governments of many low income countries must also become more engaged in ensuring the systems that will deliver these goods to health facilities. Despite the almost universal provision of vaccines by UNICEF for many of the childhood vaccine preventable diseases, some countries have had routine vaccine coverage, as measured by 3 doses of DTP at age 12 years, at levels much below 50%. And peripheral health facilities in many countries have repeated rupture of stocks of vaccines, and also of medicines for AIDS, TB, malaria and other medicines on the WHO essential drugs list.

Maternal and child health

There are huge global differentials in maternal mortality: the risk of a woman dying as a result of pregnancy or childbirth during her lifetime is about one in six in the poorest parts of the world compared with about one in 30,000 in Northern Europe. Sub-Saharan Africa and south Asia have the highest burden of maternal mortality. Most maternal deaths happen around the time of delivery, most commonly due to haemorrhage. Other important causes include hypertensive diseases and infections, and in some parts of the world, unsafe abortion and puerperal infection carry a huge risk. Surprisingly, a large proportion of maternal death takes place in hospitals; these include women who come to the hospital in a moribund state too late to benefit from care, but also those who arrive with treatable complications but do not receive timely and effective interventions and those admitted for normal delivery that subsequently develop complications. A number of interventions are effective. A strategy of encouraging women to routinely deliver at health centres, with skilled midwives as the main providers of care, backed up by access to referral-level facilities, is among the most cost-effective options for low income settings. A broader perspective to health, reducing the economic and social vulnerability of pregnant women through education of girls, poverty reduction and women’s empowerment is central to any strategy.

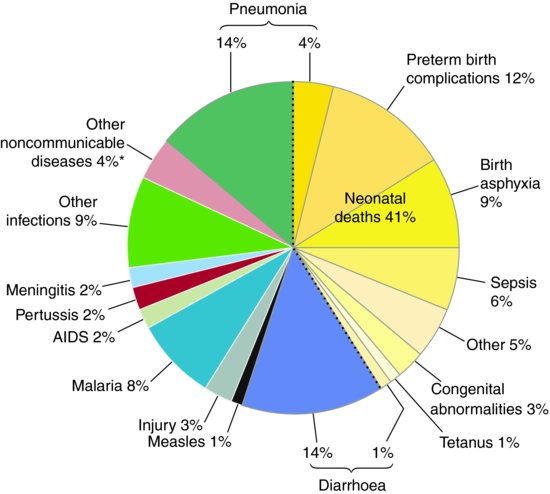

Although child mortality has been declining worldwide in recent times, yet 8.8 million children die every year before their fifth birthday. The most important causes of child death are pneumonia, diarrhoea and preterm birth complications (see Figure 22.1). Most of these deaths occur in Africa and south Asia, particularly, India, Nigeria, Democratic Republic of Congo, Pakistan and China. The majority of these deaths occur in the neonatal period, during which time preterm birth complications and birth asphyxia are particularly important. Interventions directed towards health education of families and communities to promote adoption of evidence-based home-care practices and improved care seeking, could avert majority of neonatal deaths in low income settings, but the coverage of these interventions remains poor.

Figure 22.1 Global causes of child mortality in 2008.

Source: Black RE; Cousens S, Johnson HL, et al. (2010) Global, regional, and national causes of child mortality in 2008: a systematic analysis. The Lancet 375: 1969–87.

Nutrition and health

WHO regards hunger and malnutrition as the gravest threats to global health. It is a challenge to human dignity, and also threatens the ability of nations to progress socioeconomically. Most deaths from hunger do not occur in high profile emergencies but in unnoticed circumstances. With economic development, the proportion of hungry people in the low-income countries has halved in the last four decades; despite this, maternal and child undernutrition remains highly prevalent in low income countries. Undernutrition is a largely preventable cause of over a third of child deaths. Vitamin A – which causes xeropthalmia – and zinc – which reduces immune function – are now among the most important micronutrient deficiencies, particularly as the burden of iodine and iron deficiencies have gone down, given the intervention programmes in many parts of the world. Suboptimal breast feeding, especially nonexclusive breast feeding in the first six months of life, is an important cause of child mortality, while maternal short stature and iron deficiency anaemia increase the risk of death of the mother at delivery. Apart from these short term consequences, damage suffered due to undernutrition in the early years of life may lead to irreversible damage, including shorter adult height, lower attained schooling, reduced adult income, and potentially greater risk of some chronic diseases due to these early life determinants.

Noncommunicable diseases

As countries move through economic development from a pre-industrial to an industrialised economy, transition occurs in the demographic and disease profile of the population. Deaths from acute infectious and deficiency diseases characteristic of underdevelopment decline, and deaths due to chronic noncommunicable diseases which result from modernisation and advanced levels of development rise – the ‘epidemiological transition’. The rapid ‘epidemiological transition’ currently taking place in many low- and middle-income countries bears many similarities to the similar transition that took place in high income countries nearly a century ago, yet there are important differences.

The transition is happening at a much faster pace, and before the disappearance of the diseases of the old world (e.g. infections, malnutrition) leading to a double burden of disease. The speed of the transition is driven by:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree