Note: Use ideal body weight. The equation above is for males. For females, multiply the result by 0.85. The use of any formula for predicting renal clearance of drugs is limited by patient variability, general health, and concurrent medical conditions.

In dosing the elderly, the general rule is to start with doses lower than those used in younger patients and to increase doses at a slower rate.

38-4. Drugs of Concern

The following drugs most often cause adverse events among the elderly, resulting in hospitalization:

■ Warfarin

■ Insulin

■ Oral hypoglycemic agents

■ Oral antiplatelet agents

The following drugs can cause psychiatric symptoms:

■ Anticholinergics

■ Narcotics

■ Tricyclic antidepressants

■ Central nervous system stimulants

■ Antiparkinson drugs

The following drugs can produce anxiety symptoms:

■ Theophylline

■ Nasal decongestants

■ β-agonists

■ Antiparkinson drugs

■ Appetite suppressants

The following drugs can contribute to nutritional deficiencies:

■ Diuretics

■ Digoxin, digitalis

■ Laxatives (overuse)

■ Sedatives (overuse)

38-5. Medication Compliance and the Older Adult

Types of noncompliant behavior in the elderly include the following:

■ Failure to take medications

■ Premature discontinuation of a medication

■ Excessive consumption of a medication

■ Use of medications not currently prescribed

Several strategies can improve patient medication compliance:

■ Limit the number of different medications, and decrease the dose frequency.

■ Simplify dosage instructions.

■ Tailor the regimen to the patient’s schedule.

■ Use compliance aids and telephone reminders.

■ Enlist the assistance of family members and friends.

38-6. Basic Components of Evaluating Drug Therapy in Older Adults

These questions should be answered in an evaluation of drug therapy:

■ Why is the drug being used? A diagnosis or reason should be given.

■ Is the drug being given correctly? The dosage, form, and schedule of administration should be analyzed.

■ Are any symptoms or complaints related to drug therapy?

■ Is monitoring of treatment ongoing?

■ What is the endpoint of therapy?

Suggestions on how to review a geriatric patient’s medications include the following:

■ Consider all medications (not just the obvious), but focus first on the most likely to cause issues.

■ Consider length of therapy, including when a drug was added or a dosage was increased or decreased.

■ Remember basic mechanisms of action.

■ Try to match reported symptoms with possible medication side effects.

■ Consider that lack of response to treatment may be related to drug therapy (for example, interactions).

■ Review lab results, if available, and recommend additional tests only if necessary.

■ Simplify medications in a manner that will aid in identifying which change caused a specific result.

38-7. Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias

Dementia is the decline in intellectual abilities (e.g., impairment of memory, judgment, abstract thinking) coupled with changes in personality. Dementia patients tend to be described as cognitively impaired.

Cognition is the mental process by which people become aware of objects of thought and perception, including all aspects of thinking and remembering. Impairment of cognition significantly affects the life of the dementia patient, his or her family members, and the community in general.

Types of Dementia

Alzheimer’s disease accounts for approximately 70% of dementias. Vascular dementias account for approximately 15% of dementias. Patients may have both Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia.

Other Causes of Dementia

■ Vascular disease and cerebrovascular accidents (strokes)

■ Neurologic disorders such as Parkinson’s disease, frontotemporal dementia, dementia with Lewy bodies, and Huntington’s chorea

■ Metabolic disorders such as hypothyroidism, alcoholism, and anemia

■ Infectious diseases such as meningitis, syphilis, and acquired immune deficiency syndrome

Clinical Presentation

Alzheimer’s disease is a progressive neurologic disease that results in impaired memory and intellectual functioning and altered behavior. Alzheimer’s disease is characterized by the slow onset of symptoms leading to loss of ability to function independently. Symptoms may include psychoses with hallucinations, illusions, and delusional thinking. As Alzheimer’s disease progresses, the brain continues to deteriorate.

Depression can cause cognitive impairment similar to that of Alzheimer’s disease and should be identified and treated.

Pathophysiology

Hallmark pathologic changes in the brain are linked to Alzheimer’s disease (i.e., neuritic plaques and neurofibrillary tangles increase). Neuritic plaques are composed of amyloid proteins deposited on neurons. Neurofibrillary tangles exist within neurons and disrupt normal function.

Neurotransmitters are also altered in Alzheimer’s disease. Acetylcholine concentrations decrease significantly.

Diagnostic Criteria

Diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease requires the presence of memory impairment and one or more of the following:

■ Aphasia (language disturbance)

■ Apraxia (impaired motor abilities)

■ Agnosia (failure to recognize objects)

■ Disturbance of executive function (e.g., planning, organizing)

Treatment Principles

When evaluating a patient for treatment of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease, review the patient’s medications and consider any that might cause mental confusion or worsen underlying disease states. Drugs that block activity of acetylcholine can worsen dementia and decrease the effectiveness of medications used to treat Alzheimer’s disease.

Anticholinergic drugs are used for a variety of conditions, ranging from depression to incontinence. Indications should be identified before treating Alzheimer’s disease. Anticholinergic effects can be additive (i.e., a combination of anticholinergic drugs can result in toxicity even when each is given at low doses; see Table 38-1).

Provide support to caregivers, and treat the patient’s behavioral and mood symptoms.

Consider a trial of a cholinesterase inhibitor, and monitor for benefits to memory and cognitive functioning.

Monitoring

Monitor memory and cognitive functions every 6–12 months.

Routinely assess behaviors and ability to perform activities of daily living (e.g., bathing, feeding, toileting, dressing).

Monitor for focal neurologic signs and symptoms that may suggest other causes of changes in cognitive function.

Drug Therapy

The pharmacologic approach to treatment falls into two categories:

■ Medications used to control behavioral and emotional symptoms

■ Medications used to slow or reverse the disease process

Symptomatic therapy

Medications used to control behavioral and emotional symptoms are used to provide symptomatic improvement and do not affect the outcome of the disease.

Anxiolytics are used to decrease anxiety and possibly agitation, motor restlessness, and insomnia. Such medications include lorazepam (Ativan), oxazepam (Serax), and buspirone (Buspar). The benzodiazepines can increase the risk of falls and injury.

Antidepressants improve depression, which can worsen the cognitive functioning of a patient with Alzheimer’s disease. Antidepressants include sertraline (Zoloft) and citalopram (Celexa).

Table 38-1. Anticholinergic Drugs That Can Worsen Alzheimer’s Disease

Class | Drugs |

Antidepressants | Highest effects: amitriptyline, amoxapine, clomipramine, protriptyline |

| Moderate effects: bupropion, doxepin, imipramine, maprotiline, trimipramine |

Antiparkinsonian agents | Benztropine, trihexyphenidyl |

Antipsychotics | Highest effects: clozapine, mesoridazine, olanzapine, promazine, triflupromazine, thioridazine |

| Moderate effects: chlorpromazine, chlorprothixene, pimozide |

Antispasmodics | Atropine, belladonna alkaloids, dicyclomine, glycopyrrolate, hyoscyamine, methscopolamine, oxyphencyclimine, propantheline, oxybutynin, flavoxate, terodiline |

Antihistamines | Highest effects: carbinoxamine, clemastine, diphenhydramine, promethazine |

| Moderate effects: azatadine, brompheniramine, chlorpheniramine, cyproheptadine, dexchlorpheniramine, triprolidine, hydroxyzine |

Antiemetic–antivertigo agents | Meclizine, scopolamine, dimenhydrinate, trimethobenzamide, prochlorperazine |

Other agents with some anticholinergic activity | Paroxetine |

Antipsychotics are used to decrease psychotic symptoms such as hallucinations and delusions. Antipsychotics such as haloperidol (Haldol), risperidone (Risperdal), and aripiprazole (Abilify) may reduce agitation and aggressiveness in dementia patients. A U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) black box warning concerning the risk of increased mortality (cardiac events and infections) is associated with the use of antipsychotics in demented elderly patients.

Sedative-hypnotics are used for short-term treatment of insomnia but can increase confusion and memory impairment. These medications include trazodone (Desyrel), zolpidem (Ambien), and temazepam (Restoril).

Cholinesterase inhibitors

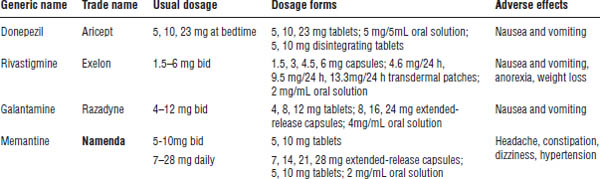

Medications used to slow or reverse the symptoms of Alzheimer’s (see Table 38-2) affect acetylcholine activity in the brain. Acetylcholine levels may be decreased by as much as 90% in Alzheimer’s disease. These levels can be increased by inhibiting the enzyme acetylcholinesterase.

Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors increase acetylcholine but do not replace lost cholinergic neurons or change the underlying pathology. This class of medications is used to prevent or slow deterioration in cognitive functioning.

The first cholinesterase inhibitor approved to treat Alzheimer’s disease was tacrine (Cognex), which proved beneficial but caused hepatotoxicity (damage to the liver).

Safer cholinesterase inhibitors include the following:

■ Donepezil (Aricept) is selective for acetylcholinesterase in the brain (i.e., not in peripheral tissues) and is approved for mild to moderate and moderate to severe dementia. A 23 mg tablet is now approved for moderate to severe dementia, but additional benefits of this higher dose are modest at best, and it has an increased incidence of adverse effects.

■ Rivastigmine (Exelon), a nonselective cholinesterase inhibitor, decreases acetylcholinesterase. It is approved for mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease and dementia associated with Parkinson’s disease.

■ Galantamine (Razadyne) is a selective acetylcholinesterase inhibitor that activates nicotinic receptors, which may increase acetylcholine. It is approved for mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease dementia.

Patient instructions and counseling

Donepezil (Aricept)

Give orally, 5 mg daily for 4–6 weeks. Increase dosage to 10 mg daily at bedtime. Take with or without food. A 23 mg dose is available that has shown statistical significance but less clear observable benefits. This higher dose causes increased adverse effects, and there is limited research to support clinical benefits.

Rivastigmine (Exelon)

Oral doses are given with a gradual dosage increase. Begin at 1.5 mg twice daily and then 3 mg twice daily, 4.5 mg twice daily, and 6 mg twice daily, with a minimum of 2 weeks between dose increases. If rivastigmine is discontinued because of adverse effects, restart at beginning dose. Take with meals in divided doses. Transdermal patch dosing begins with 4.6 mg every 24 hours, once daily for 4 weeks. It then increases to 9.5 mg every 24 hours, once daily.

Table 38-2. Drugs Used to Treat Alzheimer’s Disease

Boldface indicates one of top 100 drugs for 2012 by units sold at retail outlets, www.drugs.com/stats/top100/2012/units.

Galantamine (Razadyne)

Doses begin with 4 mg twice daily for 4 weeks, 8 mg twice daily for 4 weeks, and then 12 mg twice daily. If galantamine is discontinued for more than a few days, restart at the beginning dose. In hepatic or renal dysfunction, doses should not exceed 16 mg/day. Do not use in instances of severe dysfunction. Take with meals in divided doses. Initiate therapy with extended-release capsules at 8 mg daily with a morning meal for 4 weeks. Increase the dose to 16 mg daily for 4 weeks and then 24 mg daily.

Adverse drug events

■ Donepezil: Side effects include nausea, vomiting, and gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms. These side effects may be minimized by increasing the dose at 6 weeks.

■ Rivastigmine: Side effects include nausea, vomiting, GI upset, and possibly significant weight loss. Adverse effects are dose related and may be lessened by increasing the dose at a slower rate.

■ Galantamine: Adverse effects include nausea, vomiting, and GI upset. Slow dose titration will decrease side effects.

N-methyl-D-aspartate–receptor antagonists

Blocking the excitotoxicity effects of the neurotransmitter glutamate at N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors has been reported to be beneficial in Alzheimer’s disease. Memantine (Namenda) is an NMDA-receptor antagonist used for moderate to severe Alzheimer’s disease dementia. There is no evidence to support memantine use in mild Alzheimer’s disease, and efficacy is modest at best in moderate Alzheimer’s dementia. Immediate-release tablets have been discontinued, and now doses begin with 7 mg daily for 1 week, with weekly increases to 28 mg daily, if tolerated.

The dose should be reduced to 14 mg daily in patients with renal impairment (CrCl less than 30 mL/min).

Side effects include drowsiness, dizziness, headache, blood pressure elevations, and motor restlessness.

Drug–drug interactions

Anticholinergic drugs will reduce the effectiveness of cholinesterase inhibitors and cause dry mouth, blurred vision, constipation, and mental confusion (i.e., conditions that are more problematic in the elderly).

Cytochrome P450 enzyme inhibitors of 2D6 and 3A4 increase levels of galantamine and donepezil by inhibiting their metabolism.

Dextromethorphan (Robitussin DM), a potent NMDA-receptor antagonist, should be used cautiously with memantine. This caution also includes co-administration with amantadine and ketamine. Smoking and nicotine products may alter levels of memantine. Concurrent use of amantadine increases the potential for adverse effects.

Parameters to monitor

■ Monitor cognitive function (e.g., poor results on mini–mental state exam, decline in performance of activities of daily living, incidence of behaviors that indicate cognitive decline).

■ Watch for signs and symptoms of toxicity.

■ Discontinue treatment with active peptic ulcer disease, severe bradycardia, and acute medical illness.

■ Perform periodic complete blood cell count and basic chemistries.

■ Look for expected benefits with the use of cholinesterase inhibitors and NMDA-receptor antagonists. Such benefits include improvement in memory, some stabilization of behaviors or mood, and possible slowing of the progression of the disease.

Nonprescription agents

High-dose vitamin E (2,000 units daily) has been recommended as an antioxidant to slow progression of Alzheimer’s disease. Vitamin E may interfere with vitamin K absorption and result in increased risk of bleeding. Increased mortality has been reported with high-dose vitamin E. The potential toxicity of high-dose vitamin E may outweigh the benefits.

Ginkgo biloba, an herb, has been used to treat symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease with reports of modest benefits. Ginkgo biloba is associated with increased risk of bleeding and hemorrhage, especially when combined with daily aspirin use, and is not recommended. There is growing evidence that ginkgo biloba does not provide any benefits over a placebo.

Observational studies of vitamin D (ergocalciferol) have shown a slowing of cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease. Clear benefits and dosage considerations will require further research.

Nondrug Therapy

The treatment of Alzheimer’s disease includes nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic therapies. Patients need to live in an environment that permits safe activities while minimizing risk.

Caregivers need training and support to deal with the behavioral and functional issues associated with this disease. Caregivers are at risk for depression and stress-related medical illnesses. Caregivers may also neglect their own health care needs and should be encouraged to maintain a healthy lifestyle.

38-8. Parkinson’s Disease

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a chronic progressive neurologic disorder with symptoms that present as a variable combination of rigidity, tremor, bradykinesia, and changes in posture and ambulation. An estimated 1 million persons in the United States suffer from PD. Approximately 60,000 new cases are diagnosed each year.

The risk of developing PD increases with age, and a substantial increase in the U.S. population of persons over 60 years of age is predicted.

Because medications are the primary treatment for PD, pharmacists play an important role in the care of these patients.

Classification

The two classes of PD are primary parkinsonism and secondary parkinsonism. Primary parkinsonism has no identified cause. Secondary parkinsonism can be the result of drug use (e.g., reserpine, metoclopramide, antipsychotics); infections; trauma; or toxins.

Clinical Presentation

Clinical signs and symptoms of PD develop insidiously, progress slowly, may fluctuate, and worsen with time despite pharmacologic therapy.

Symptoms

Tremors at rest may begin unilaterally and are present in 70% of PD patients. Tremors that do not occur during sleep may worsen with stress.

Rigidity of limbs and trunk may develop. The face may have a masklike expression. Patients may have difficulty dressing or standing from a seated position.

Akinesia (the absence of movement) and bradykinesia (slowed movements) can occur. Postural instability with abnormal gait and an increased risk of falls are often experienced.

Depression and possibly dementia are possible nonmotor symptoms of PD.

Other symptoms include micrographia (small writing), drooling, decreased blinking, constipation, and incontinence. Patients may develop dysphagia (difficulty swallowing) and dysarthia (difficulty with speech).

Pathophysiology

PD involves a progressive degeneration of the substantia nigra in the brain with a decrease in dopaminergic cells (more than the typical decrease that accompanies normal aging). The most significant neurotransmitter in PD is dopamine, but other neurotransmitters may play a role (e.g., acetylcholine, glutamate, GABA [γ-aminobutyric acid], serotonin, norepinephrine).

The etiology is unknown, but genetic susceptibility is possible. Environmental toxins combined with aging may also be responsible for the development of PD.

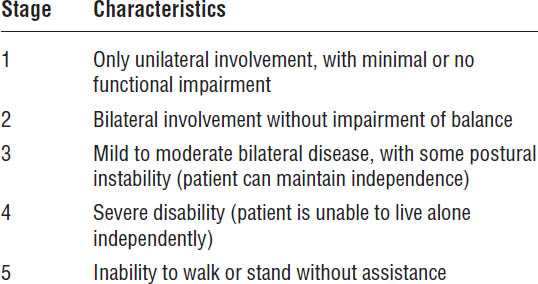

Diagnostic Criteria

Clinical diagnosis is based on the presence of bradykinesia and either rest tremor or rigidity. The stages of the disease are described in Table 38-3.

Treatment Principles and Goals

The goal for treating PD is to relieve symptoms and maintain or improve quality of life for the patient. Treatment should be initiated when functional impairment and discomfort for the patient or caregiver occurs.

A safe environment and caregiver support programs in addition to medications will often allow patients to remain in the community.

Table 38-3. The Stages of Parkinson’s Disease

Drug Therapy

Mechanism of action

Medications increase dopamine or dopamine activity by directly stimulating dopamine receptors or by blocking acetylcholine activity, which results in increased dopamine effects (Table 38-4).

Selection of an initial medication to treat PD may vary with the prescriber. Most therapy will begin with levodopa or with a direct dopamine agonist. Some experts will initiate therapy with a dopamine agonist in patients younger than 60 years of age. All medications that increase dopamine activity should not be discontinued abruptly because of the risk of sudden onset of Parkinson’s symptoms.

Levodopa (Sinemet when combined with carbidopa)

Levodopa is the most effective drug in the treatment of PD and is converted to dopamine in the body. It is given with carbidopa, a decarboxylase inhibitor that prevents the peripheral conversion of levodopa to dopamine, thereby reducing nausea and vomiting while allowing more drug to pass through the blood–brain barrier.

Generally, doses are increased gradually to minimize the risk of side effects with the goal of improving symptoms with the lowest dose possible. In maintenance therapy or advanced disease, doses are given before meals to facilitate absorption. Carbidopa effectively inhibits peripheral conversion of levodopa at doses of 100 mg/day.

Levodopa provides benefits to all stages of PD, but chronic use is associated with adverse effects. Patients may have periods of good mobility alternating with periods of impaired motor function.

Dopamine agonists

Dopamine agonists work directly on dopamine receptors and do not require metabolic conversion. They may be used as monotherapy or as adjunctive therapy, allowing lower doses of carbidopa-levodopa. Some clinicians will initiate therapy with a direct dopamine agonist in younger newly diagnosed patients. Pramipexole (Mirapex), bromocriptine (Parlodel), and ropinirole (Requip) are available orally, and rotigotine is administered as a transdermal patch.

Apomorphine (Apokyn) is a direct-acting dopamine agonist that is administered by subcutaneous injection. It causes significant nausea and vomiting, and an antiemetic (e.g., trimethobenzamide) is given concurrently. Apomorphine is reserved for the treatment of “off” episodes associated with advanced disease. Monitor for orthostatic hypotension after initial doses and with dose escalation.

Selective monoamine oxidase type B inhibitors

Monoamine oxidase (MAO)-B inhibitors may be used as initial therapy in early PD and as adjunct treatment for more advanced disease. Although neuroprotective properties have been seen in animal models, benefits as monotherapy are modest.

With doses used for PD, adverse effects from consuming tyramine-containing foods would not be expected.

Catechol-O-methyl transferase inhibitors

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree