GERIATRICS

Carla Bouwmeester, PharmD, BCPS, and Michael R. Brodeur, PharmD, CGP, FASCP

CASE

N.W. recently started a geriatric-specialty APPE rotation at a program of all-inclusive care for the elderly. She is assigned to an interdisciplinary team and reports to the daily morning meeting. The team reviews the on-call report that includes a patient who fell and broke her hip, abnormal laboratory values for a patient in a rehabilitation facility, a patient who received his roommate’s medications last night at an assisted living facility, and a refill request for acetaminophen. After the morning meeting, the pharmacy resident reviews with N.W. the list of patients who need international normalized ratios (INRs) taken today at the adult day health center and a nearby assisted living facility. While they are talking, a nurse practitioner inquires about the use of medications to prevent intractable skin itching in patients with dementia.

WHY IT’S ESSENTIAL

The number of people in the United States age 65 years and older is now more than 40.4 million.1 Over the past 20 years, there has been an increase in life expectancy due to decreasing death rates in children and in those over the age of 65. Combined with the historically elevated birth rates of the baby boomer generation, a 31% increase in the number of Americans who will turn 65 is expected over the next few decades.1 As this generation ages, there will be a significant shift in the number of elderly persons. Not only will there be more persons over the age of 65, but there will also be an increase in the oldest old. Even now, there is an increase in the number of the oldest old who live alone, particularly women, racial minorities with no living children, and unmarried persons with no living children or siblings.2 This raises concerns over the demand for support systems and healthcare services for this vulnerable population.

Currently, the percentage of people over the age of 65 who consider themselves to be in fair or poor health is 24%.3 It is estimated that the number of elderly people with poor health will parallel the population increase and rise sharply by the year 2030.2 As of 2010, 90% of Medicare beneficiaries reported having one or more chronic medical conditions and 46% had three or more.4

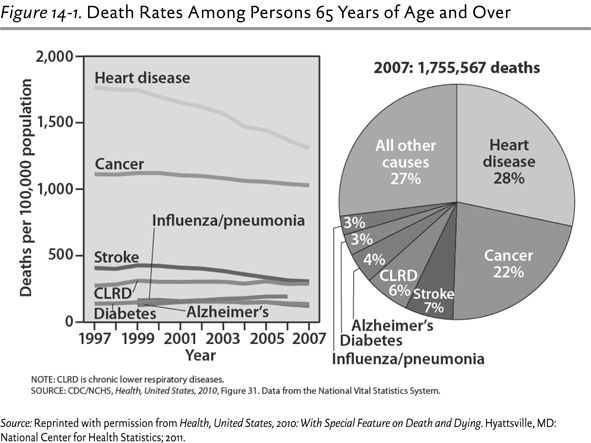

- The leading causes of death in patients older than 65 years continue to be heart disease, cancer, stroke, chronic lower respiratory diseases, Alzheimer’s disease, diabetes, and pneumonia or influenza (see Figure 14-1).

- Although the overall incidence of heart disease and stroke decreased over the past decade, the prevalence of these conditions increases with age.

- It is estimated that 67% of men and 80% of women over the age of 75 have hypertension, compared with only 33% to 34% of men and women aged 45 to 54.3

- The latest data reveal that 27% of noninstitutionalized people over the age of 65 have diabetes.3

- Compared to the other leading causes of death, Alzheimer’s disease–related deaths increased by 66% between 2000 and 2008, and it is now estimated that one in eight people aged 65 or older have Alzheimer’s disease5 (and over 89% of the residents in long-term care facilities have some form of cognitive or mental impairment).4

As the disease burden increases in the elderly, so does the percentage of prescription medication use. More than 90% of people over the age of 65 take at least one prescription medication, and two out of three people take three or more prescription medications.3 The number of people in this age group taking multiple medications has risen from 35.3% in 1994 to 65% in 2008, increasing the potential for medication-related problems.3 It is estimated that more than 17% of hospital admissions for the elderly are a direct result of adverse drug reactions (ADRs).6 In 2008, the Institute of Medicine report Retooling for an Aging America recommended increased recruitment and retention of geriatric specialists in all health professions.7

Pharmacists can play a crucial role in the prevention of medication incidents by preventing drug interactions, monitoring medication therapy, and educating patients on safe medication use. Based on the estimated growth of the elderly population, you will encounter these patients in nearly every area of pharmacy practice. During a geriatrics rotation, you will observe how pharmacists interact with this population through dispensing medications, providing patient counseling, managing drug therapy, and contributing to interdisciplinary care teams. The rotation will allow you to gain confidence and apply your knowledge to caring for patients with sensory impairment, physical disabilities, cognitive limitations, psychological challenges, and renal and hepatic deficiencies and those nearing the end of life. Completing a geriatric rotation will familiarize you with the important issues affecting seniors and expand your understanding of the substantial impact a pharmacist can make while serving this patient population.

Contact the preceptor prior to the rotation to discuss logistics (parking, arrival time, meeting place, etc.), dress code, required readings, and disease states to review. The comorbidities of your patient population will vary depending on the setting of the rotation; however, you will encounter most of the common chronic medical conditions. A detailed list of disease states and geriatric syndromes can be found in the Geriatric Pharmacy Curriculum Guide (second edition) (available on the American Society of Consultant Pharmacists [ASCP]) website. The most common disease states and conditions encountered in geriatric rotations include the following:

- Cardiovascular

Arrhythmias

Arrhythmias

Heart failure

Heart failure

Hyperlipidemia

Hyperlipidemia

Hypertension

Hypertension

- Endocrine

Diabetes mellitus

Diabetes mellitus

Erectile or sexual dysfunction

Erectile or sexual dysfunction

Thyroid disease

Thyroid disease

- Gastrointestinal

Constipation

Constipation

Diarrhea

Diarrhea

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD)

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD)

- Hematologic

Anemia

Anemia

- Infectious disease

Nosocomial infections

Nosocomial infections

Pneumonia

Pneumonia

Vaccine-preventable diseases (influenza, herpes zoster, pertussis)

Vaccine-preventable diseases (influenza, herpes zoster, pertussis)

- Musculoskeletal

Gout

Gout

Osteoarthritis

Osteoarthritis

Osteoporosis

Osteoporosis

Rheumatoid arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis

- Neurologic

Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias

Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias

Cerebrovascular accident (CVA) and transient ischemic attack (TIA)

Cerebrovascular accident (CVA) and transient ischemic attack (TIA)

Pain and neuropathy

Pain and neuropathy

Parkinson disease

Parkinson disease

Seizures

Seizures

- Ophthalmology

Cataracts

Cataracts

Glaucoma

Glaucoma

Macular degeneration

Macular degeneration

- Psychiatry

Anxiety

Anxiety

Bipolar disorder

Bipolar disorder

Depression

Depression

Schizophrenia

Schizophrenia

Sleep disorders

Sleep disorders

- Nephrology and urology

Benign prostatic hyperplasia

Benign prostatic hyperplasia

Chronic kidney disease

Chronic kidney disease

Urinary incontinence

Urinary incontinence

- Respiratory

Asthma

Asthma

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)

- Syndromes and special problems in the elderly

Falls and gait disorders

Falls and gait disorders

Frailty syndrome

Frailty syndrome

Functional decline

Functional decline

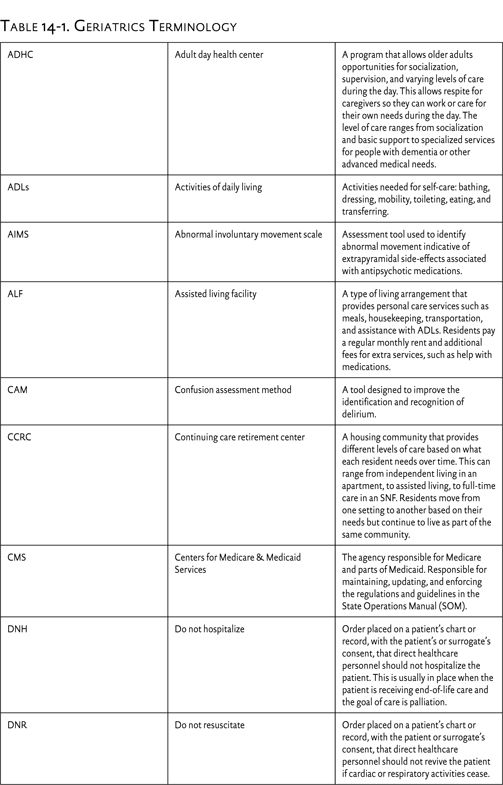

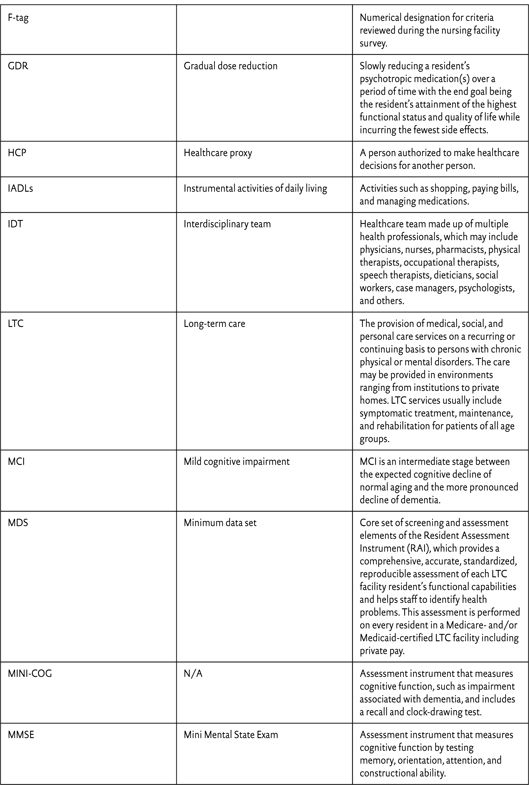

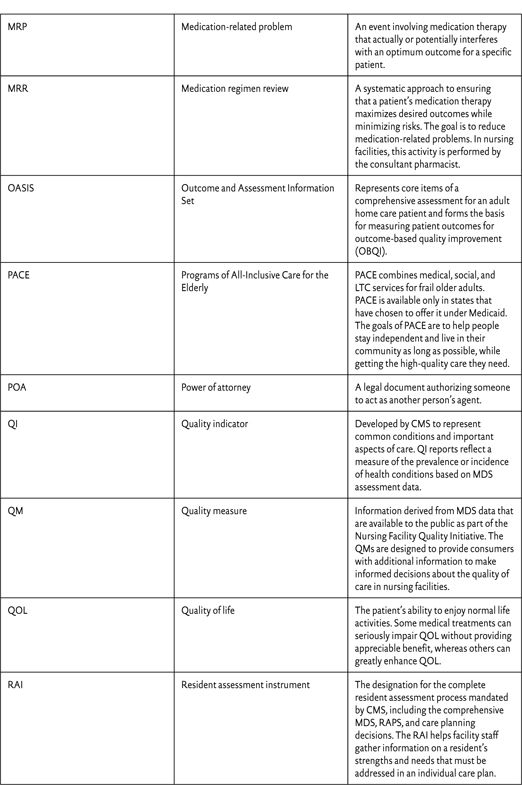

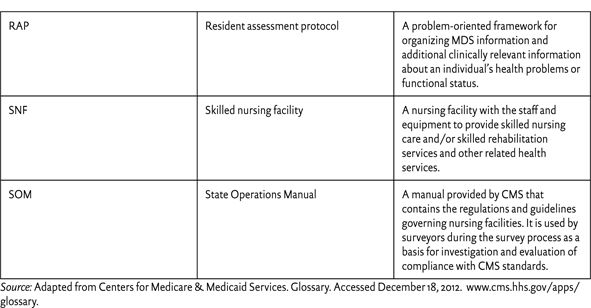

It will also be helpful to familiarize yourself with the terminology associated with long-term care and geriatric APPE rotations (see Table 14-1), pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic changes in the elderly, medications to avoid in the elderly, and any state or federal regulations specific to your practice site.

CASE QUESTION

The pharmacy resident and N.W. are responsible for identifying and tracking medication incidents. These incidents include any medication-related events from prescribing to administration, including order entry, dispensing, delivery, dosing frequency and timing, forgotten or refused doses, duplication of therapy, and adverse events. Identify the potential medication incidents and geriatric syndromes discussed during the morning meeting.

A TYPICAL DAY

Programs of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly

Programs of All-inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE) are based on the medical home model and are often described as “nursing homes without walls.” These programs are designed to care for medically complex and frail seniors in the comfort of their homes for as long as safely possible. Participants must be at least 55 years old, live within a defined geographic area, and be eligible for nursing home care although still living safely in the community. The PACE program provides all services covered by Medicare and Medicaid and assumes full financial responsibility for the patient’s medical care. This may include physical and occupational therapy, social work, medications (both prescription and over-the-counter [OTC]), medical specialists, transportation to medical appointments, adult day healthcare, hospital stays, and nursing home placement if necessary in the future. Each PACE program also functions as a Medicare Part D company and provides medications through affiliated or independent pharmacies.

Pharmacy services in PACE programs vary by location but generally include involvement in the interdisciplinary team morning meetings, patient counseling and education, medication regimen reviews, and committee meetings. Every 6 months, each PACE participant is involved in the care planning process to assess progress and establish clinical goals for the next 6 months. Prior to the care plan meeting, each discipline conducts a thorough review of the patient’s current health status, interventions made by the team, and progress toward established goals of therapy. This is an ideal time for you to review the patient’s medication use over the past 6 months and make recommendations regarding drug interactions, adverse events, side effects, monitoring, duplicate therapy, and untreated conditions. You may also provide medication counseling directly to patients in the PACE clinic or in the patients’ homes. Some PACE programs also rely on pharmacists to manage anticoagulation and chronic disease states, giving you the opportunity to get involved in INR point-of-care testing, insulin teaching, or education on the proper use of inhalers. Finally, pharmacists are often involved in committees such as quality assurance, performance improvement, compliance, infection control, hospice services, pharmacy and therapeutics (formulary), and fall prevention. You may be asked to attend committee meetings, assist in preparing reports, present in-service learning programs, or perform medication use evaluations for other healthcare professionals.

“My experience at the PACE program enhanced my understanding of caring for older adults and taught me to consider each patient as a whole rather than managing each disease state separately. I now have a better understanding of the role and significance of the pharmacist on the healthcare team in counseling patients, providing information and recommendations to prescribers and caregivers, performing medication reviews, medication therapy management, presenting in-service educational programs, and ultimately reducing medication-related problems.”—Student

Assisted Living

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree