Helene Korey Marley

Genitourinary Surgery

Advances in genitourinary surgery, with the use of robotics, laparoscopic techniques, cryotherapy, brachytherapy, lasers, ultrasonography, lithotripters, innovative diagnostic measures, and minimally invasive surgical approaches, have expanded treatment options. As urologic surgery becomes more complex and far more precise, the perioperative nurse is challenged to maintain up-to-date knowledge, documented competence, and new technical skills. More procedures are performed on an ambulatory or short-stay basis, allowing limited time for patient and family education and discharge planning. The success of surgical intervention and patient outcomes depends greatly on the nurse’s ability and knowledge in designing, developing, and implementing an effective perioperative plan of care.

Surgical Anatomy

The normal genitourinary system includes one pair of kidneys, two ureters, the urinary bladder, the urethra, and the prostate gland in the male. Also considered essential to the genitourinary system are the adrenal glands, male reproductive organs, and the female urogynecologic system.

Urine is excreted by the kidneys and conveyed to the bladder through the ureters. Urine is stored in the bladder, which serves as a reservoir until its full capacity (350 to 700 mL) is reached, and is eliminated from the body by way of the urethra. Normal urinary output ranges from 0.5 to 1 mL/kg of body weight per hour for the average adult.

Kidneys

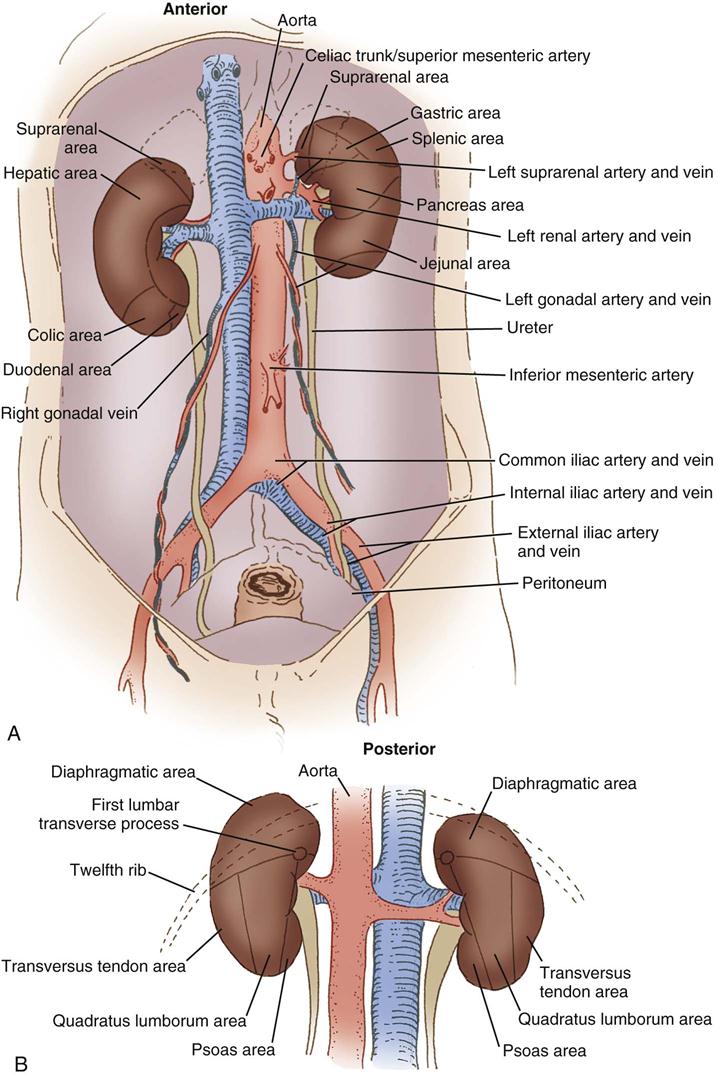

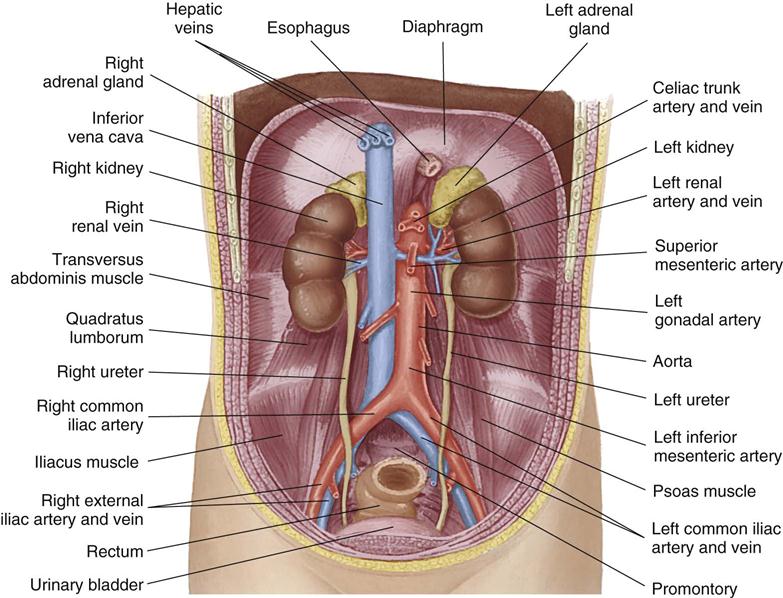

The kidneys are located in the retroperitoneal space along the lateral borders of the psoas muscle, one on each side of the vertebral column at the level of the twelfth thoracic to the third lumbar vertebrae. Usually the right kidney is several centimeters lower than the left because the liver rests superior and anterior to the right kidney (Figure 15-1).

Each kidney is surrounded by a mass of fatty and loose areolar tissue known as pararenal fat. A capsule enclosing the renal space is known as the fascia renalis. This is composed of Gerota fascia (anterior renal fascia) and Zuckerkandl fascia (posterior renal fascia). These structures help keep the kidneys in their normal anatomic position. The anterior and posterior relationships of the kidneys are shown in Figure 15-2.

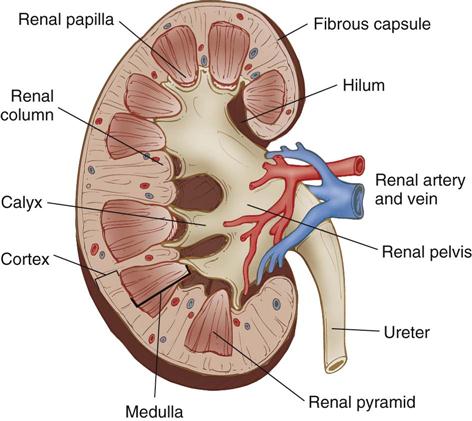

On the medial side of each kidney is a concave area known as the hilum, through which the renal artery and vein enter and exit. The renal pelvis, a funnel-shaped structure that lies within the kidney and posterior to the renal vascular pedicle, divides into several branches called calyces (Figure 15-3). When surgery is indicated in these structures, a posterior flank approach is preferred. When surgery for removal of a mass is anticipated, a transabdominal or thoracoabdominal incision may be chosen.

The kidneys are highly vascular organs that process approximately one fifth of the body’s entire volume of blood at any one time. The blood supply to the kidney is conveyed through the renal artery (a large branch of the aorta) and leaves through the renal vein. On entering the kidney, the renal artery divides into anterior and posterior sections. These undergo further division into interlobular arteries from which smaller afferent branches pass to the glomeruli. Efferent arterioles in the glomeruli then pass to the tubules of the nephron.

The renal lymphatic supply originates beneath the capsule of the kidney and empties into the lumbar lymph nodes at the junction of the renal vascular pedicle and aorta. The nerves of the autonomic (involuntary) nervous system originate from the lumbar sympathetic trunk and from the vagus nerve. Removal of the nerve pathways does not impair renal function. The renal artery and vein with their accompanying nerves and lymphatics are referred to as the pedicle of the kidney.

Adrenal Glands

The adrenal glands lie retroperitoneally beneath the diaphragm, capping the medial aspects of the superior pole of each kidney. On the right side the gland is triangular and adjacent to the inferior vena cava; on the left side it is a rounded, crescent-shaped gland posterior to the stomach and pancreas. Each adrenal gland has a medulla, which secretes epinephrine (adrenaline), and a cortex, which secretes steroids and hormones. Secretions from the adrenal cortex are influenced by the activity of the pituitary gland. The adrenal glands are liberally supplied with arterial branches from the inferior phrenic and renal arteries and from the aorta. Venous drainage is accomplished on the right side by the inferior vena cava and on the left by the left renal vein. The lymphatic system accompanies the suprarenal vein and drains into the lumbar lymph nodes.

Ureters

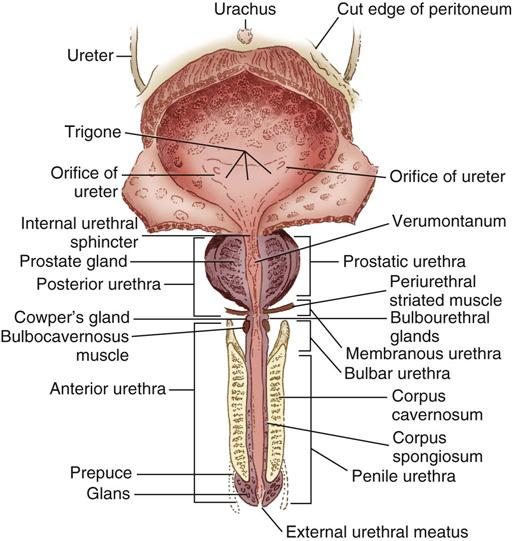

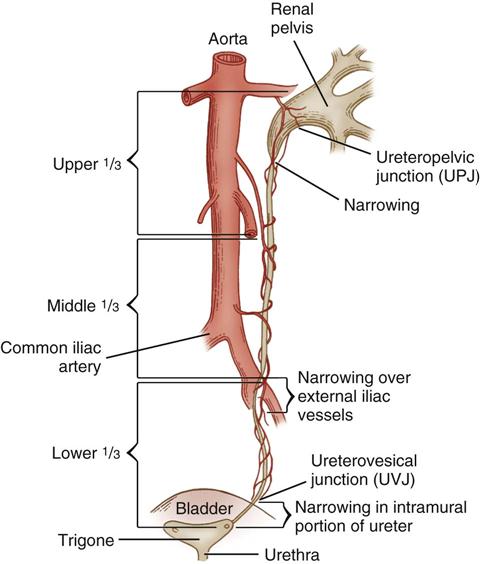

Each ureter is a continuation of the renal pelvis. The ureter extends in a smooth S curve from the renal pelvis to the base of the bladder (Figure 15-4). It is approximately 25 to 30 cm long and 4 to 5 mm in diameter in the adult. This fibromuscular cylindric tube is lined by transitional epithelium (urothelium) and lies on the psoas muscle, passing medially to the sacroiliac joints and laterally to the ischial spines. As urine accumulates in the renal pelvis, slight distention initiates a wave of muscular contractions. This peristaltic activity continues down the ureter, propelling urine into the bladder.

Urinary Bladder

The adult urinary bladder is a hollow, muscular viscus that acts as a reservoir for urine until micturition (voiding) occurs. It has an outer adventitial layer and inner urothelial layer. The trigone, a triangular area, forms the base of the bladder. The three corners of the trigone correspond to the orifices of the ureters and the bladder neck (opening of the urethra) (Figure 15-5). The ureteral orifices, on the proximal trigone at the interureteric ridge, are 2.5 cm apart. The bladder neck (internal sphincter) is formed from converging detrusor muscle fibers of the bladder wall that pass distally to form the smooth musculature of the urethra. Physiologically the bladder fills with urine and expands into the abdominal cavity. The extraperitoneal location is advantageous because a suprapubic (above the pubic arch) incision may be performed without violating the peritoneum and potentially causing intraperitoneal complications.

The main arterial supply of the bladder comprises the superior, middle, and inferior vesical arteries. These vessels are derived from the internal iliac (hypogastric) artery, the obturator and inferior gluteal arteries, and in females the uterine and vaginal arteries. The bladder has a rich venous supply that drains into the internal iliac (hypogastric) vein. The lymphatic system is served by the vesical, external, and internal iliac and common iliac lymph nodes.

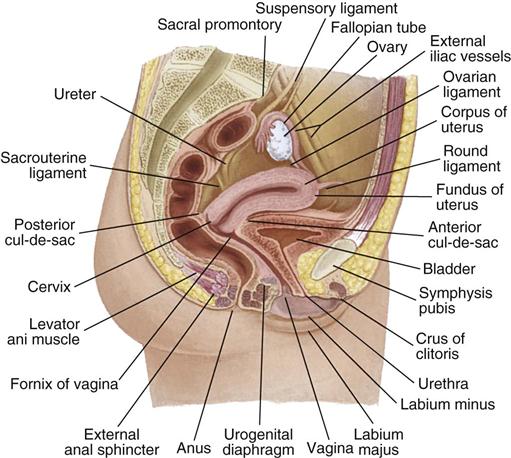

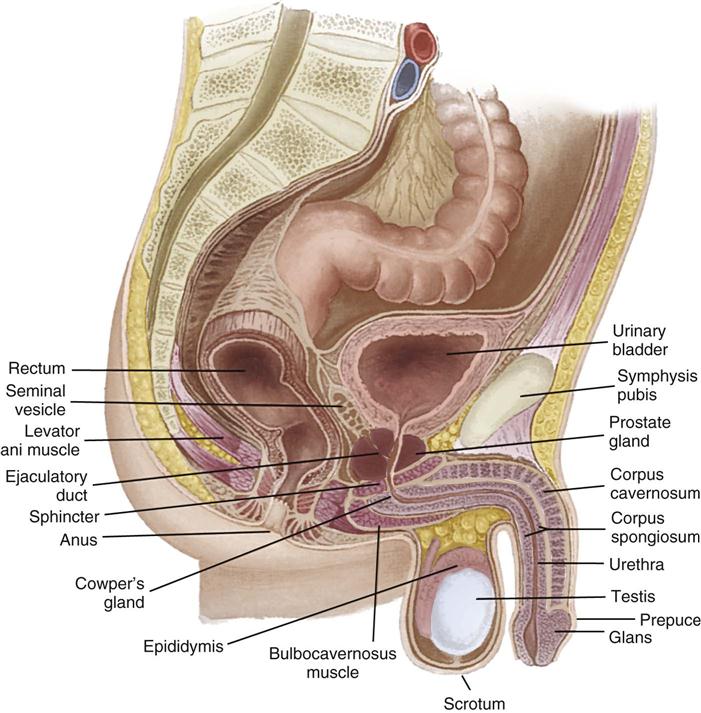

The bladder’s size, position, and relationship to the bowel, rectum, and reproductive organs varies according to the bladder’s distention. In the female the vagina lies dorsal to the base of the bladder and parallel to the urethra (Figure 15-6). In the male the prostate gland is interposed between the bladder neck and the urethra (Figure 15-7). These anatomic relationships influence the symptoms that a patient experiences preoperatively and are important landmarks during pelvic surgery.

The process of bladder evacuation appears to be initiated by nerve cells from the sacral division of the autonomic nervous system. These sacral reflex centers are controlled by higher voluntary centers in the brain. Stimulation of the sacral centers results in contraction of the bladder muscles and relaxation of the bladder outlet sphincters. Muscles inside and adjacent to the urethral wall and from the pelvic floor maintain closure of the sphincters of the bladder, thus enabling continence.

Urethra

The male urethra, normally 20 to 25 cm long, extends from the bladder neck to the tip of the penis and varies in diameter from 7 to 10 mm. It is divided into two portions: the proximal (sphincteric) urethra and the distal (conduit or anterior) urethra, both of which undergo further subdivision. The proximal urethra is commonly referred to as the posterior urethra, where it is elevated by the verumontanum, extending from the bladder neck through the prostate and the membranous portion. Within the posterior urethra lie the prostatic and membranous portions (see Figure 15-5). As the urethra exits the prostate and crosses the pelvic (urogenital) diaphragm, it is called the membranous urethra. The distal urethra, commonly called the anterior urethra, is subdivided into the bulbar, pendulous (penile), and glandular urethras. The bulbar urethra is the area most prone to urethral strictures in the male. The prostatic urethra is approximately 3 cm long and is the widest portion of the urethra. On the floor of the prostatic urethra is the verumontanum, which contains the openings of the ejaculatory ducts. The membranous urethra is the shortest portion, measuring approximately 2.5 cm and extending from the external sphincter to the apex of the prostate. The penile, or pendulous, urethra lies within the corpus spongiosum. The urothelium of the urethra is continuous with that of the bladder.

The female urethra is a narrow membranous tube about 3 to 5 cm long and 6 to 8 mm in diameter. Slightly curved, it lies behind and beneath the symphysis pubis, anterior to the vagina. It passes through the internal and external sphincters and the urogenital diaphragm. The periurethral glands of Skene open on the floor of the urethra just inside the meatus. Because the female urethra is so short and in proximity to the anal and vaginal areas, microorganisms find easy access to the bladder and can cause urinary tract infections (UTIs).

Prostate Gland

The prostate gland is a donut-shaped organ composed of fibromuscular and glandular components. It is located at the base of the bladder neck and completely surrounds the urethra. The gland is about 4 cm at the base, is about 2 cm in depth, and normally weighs 20 to 30 g (see Figures 15-5 and 15-7).

The four glandular regions within the prostate have two major zones (the peripheral zone and the central zone) and two minor zones (the transitional zone and the periurethral zone). Many clinicians still refer to prostate lobes as intraurethral lobes (right and left lateral) and extraurethral lobes (posterior and median). The posterior lobe is readily palpable during rectal examination and prone to cancerous degeneration. Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH, often referred to as hypertrophy) generally occurs in the transitional zone (intraurethral lobe).

Behind the prostatic capsule is a fibrous sheath known as the true prostatic capsule, which separates the prostate gland and the seminal vesicles from the rectum. This fascia is an important landmark during perineal prostatectomy.

The lobes of the prostate gland secrete highly alkaline fluid that dilutes the testicular secretion as it is excreted from the ejaculatory ducts. These secretions are believed to be essential to the passage of spermatozoa and helpful in keeping them alive. The arterial supply to the prostate is derived from the pudendal, inferior vesical, and hemorrhoidal arteries.

Male Reproductive Organs

The male reproductive organs include several paired structures: the testes, epididymides, seminal ducts (vasa deferens), seminal vesicles, ejaculatory ducts, and bulbourethral glands. Other organs of the reproductive tract are the penis, prostate gland, and urethra.

The scrotum is located behind and below the base of the penis and in front of the anus. Within the scrotum are two cavities, or sacs, that are lined with smooth, glistening tissue—the tunica vaginalis. Normally a small amount of clear fluid is contained in the tunica vaginalis. Each loose sac contains and supports a testis, an epididymis, and some of the spermatic cord. The two sides of the scrotum are separated from each other by a median raphe (septum).

The testes manufacture the spermatozoa and also contain specialized Leydig cells that produce the male hormone testosterone. Each testis consists of many tubules in which the sperm are formed, surrounded by dense capsules of connective tissue. The tubules coalesce and continue into the adjacent epididymis, where the sperm mature and are stored. At the upper pole of the testis is the appendix testis, a small body that may be pedunculated (stalked) or sessile (flat).

The epididymis is a long, convoluted duct located along the posterolateral surface of the testis. It is closely attached to the testicle by fibrous tissue and secretes seminal fluid, which gives the sperm a liquid medium in which to migrate. The vas deferens (ductus deferens, seminal duct) is a distal continuation of the epididymis as it enters the prostate gland and conveys the sperm to the seminal vesicle.

The vas deferens extends from the epididymis into the abdomen and lies within the spermatic cord in the inguinal region. The spermatic cord also contains veins, arteries, lymphatics, nerves, and surrounding connective tissue (cremaster muscle), which give support to the testes. The terminal portion of each vas deferens is called the ejaculatory duct; it passes between the lobes of the prostate gland and opens into the posterior urethra.

The accessory reproductive glands include the seminal vesicles, prostate gland, and bulbourethral gland. The seminal vesicles unite with the vas deferens on either side, are situated behind the bladder, and produce protein and fructose for the nutrition of the sperm cell. Sperm and prostatic fluid are discharged at the time of ejaculation.

The Cowper glands (bulbourethral glands) are located on each side at the juncture of the membranous and bulbar urethras. Each gland, by way of its duct, empties mucous secretions into the urethra.

The penis is suspended from the pubic symphysis by the suspensory ligaments. The penis contains three distinct vascular, spongelike bodies surrounding the urethra: two outer bodies called the right corpus cavernosum and left corpus cavernosum and an inner body, the corpus spongiosum urethrae. These tissues contain a network of vascular channels that fill with blood during erection (see Figure 15-7). At the distal end of the penis the skin is doubly folded to form the prepuce, or foreskin, which serves as a covering for the glans penis. The glans penis contains the urethral orifice.

Perioperative Nursing Considerations

Assessment

Patients entering a hospital or ambulatory surgery unit for genitourinary surgery may exhibit many emotions and reactions, including fear, embarrassment, helplessness, hostility, anger, and grief. To most, a successful surgical outcome is of prime importance. The urology patient population varies from infants with congenital anomalies to elderly people with physiologic impairments. Because many procedures are performed on an ambulatory basis, the nursing staff must prepare to quickly meet patients’ specific needs, from preoperative teaching to postoperative home care. The patients’ families need to be involved in this preparation process. Patient education begins in the surgeon’s office. Communication between the office and perioperative nursing staff allows continuity of care and increases the efficiency and effectiveness of surgical procedures.

In addition to routine admission information, the perioperative nurse will obtain the patient’s urologic and cardiac histories. This information includes but is not limited to vital signs, allergies (including latex), the patient’s primary problem, history of the present illness, nature of symptoms, and limitations imposed by the disease condition. In some cases patients may be seen who are not having a primary urologic procedure but instead are scheduled for an ancillary urologic procedure (e.g., insertion of ureteral catheters or stents to facilitate positive identification of the ureters and reduce the potential for severing or ligating them during pelvic or abdominal procedures). All data pertinent to the proposed operative procedure should be reviewed. Nursing observation should include the patient’s general physical appearance as well as nonverbal behaviors, such as restlessness, which may indicate discomfort or anxiety. Any limitations in mobility or sensory deficits should be noted. Urologic procedures frequently require positions that create unusual stress for the patient, both anatomic and physiologic, such as compression of the vena cava and dependent lung during lateral positioning. Also large amounts of irrigating fluids are frequently used intraoperatively in urologic procedures, which may affect the patient’s electrolyte status. Assessment provides the perioperative nurse with data adequate to support preoperative planning, intraoperative implementation, and postoperative evaluation.

The patient may undergo several studies preoperatively, including measurement of levels of serum and urine electrolytes, blood glucose, and blood urea nitrogen (BUN); urinalysis and urine cultures; cardiac enzymes; complete blood count (CBC); prothrombin time (PT) and partial thromboplastin time (PTT); blood chemistry profiles (see the laboratory values in Appendix A); electrocardiogram (ECG); and chest x-ray examination. The nurse reviews the patient’s medical history, focusing on medication use (including the use of over-the-counter medications and herbal supplements), any infectious processes, or chronic diseases. Specific genitourinary studies can be found in the patient’s medical record. They may encompass all or some of the following: computed tomography (CT) scans, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), bone and dual energy x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) scans, positron emission tomography (PET), ProstaScint scans, intravenous (IV) pyelograms or urograms (IVPs or IVUs, respectively), genitourinary flat plate (KUB [kidney, ureter, bladder]), urinary flow studies, fluoroscopic examinations (angiography, cavernosography), prostate-specific antigen (PSA), and ultrasonography. After the nurse reviews the medical record, assessment information is compiled, perioperative nursing diagnoses are identified, and the perioperative plan of care is formulated.

Nursing Diagnosis

Nursing diagnoses related to the care of patients undergoing genitourinary surgery might include the following:

Outcome Identification

Outcomes identified for the selected nursing diagnoses could be stated as follows:

• The patient will verbalize an acceptable anxiety level to the perioperative nurse.

• The patient will be free from injury related to the surgical position.

• The patient will demonstrate or regain a normal pattern of urinary elimination.

• The patient will maintain adequate fluid volume and electrolyte balance.

• The patient will maintain adequate oxygen supply and alveolar ventilation.

• The patient will discuss fears and concerns regarding sexual function.

Planning

Plans of care are the organizing framework for perioperative nursing activities, wherein nursing interventions are clinical processes in a quality health outcome model. Frequently the urology patient presents a complex medical picture. Any alterations in the patient’s physical, mental, or emotional status may greatly influence both the surgical and the postoperative course. A review of the patient’s record; communication with the patient or family; recognition of specific psychosocial, cultural, ethnic, and spiritual needs of the patient and family; and knowledge gained from other members of the patient care team are all used to formulate the nursing database (see the Sample Plan of Care).

Implementation

The perioperative nurse begins implementation of the patient care plan during the patient interview. Information that is concise and simply presented enhances the final surgical outcome. Meeting the patient’s emotional needs is a nursing priority. A calm patient retains more information and is cognitively and emotionally more receptive to perioperative teaching. The nurse provides explanations of what to expect throughout the operative period to allay the patient’s fears and nurture confidence in the nursing care provided. Establishment of this relationship is key to assisting patients to minimize the effect of the surgical experience on their coping ability and to be emotionally comfortable. Perioperative nursing care requires not only the collection of pertinent patient data but also the coordination of numerous supplies and equipment to support the smooth implementation of the plan of care.

Patient Safety.

The perioperative nurse considers several factors in advocating for the patient during the intraoperative period. Institutions have various protocols and processes in place to support patient safety. A critical safety protocol that the nurse is responsible to follow is to ensure the correct patient, correct procedure, and correct site surgery. Such a protocol includes proper patient identification, proper operative site identification, proper procedure identification, and proper medication identification. All wrong site, wrong procedure, and wrong patient surgery occurrences are considered sentinel events by The Joint Commission (TJC). In addition, the Association of periOperative Registered Nurses (AORN) has established guidelines for patient safety (AORN, 2012a).

To fulfill these requirements, preoperative verification, surgical site marking, and time-out processes must occur for every surgical procedure. What the patient expresses as the intended surgical procedure is compared with what is documented on the operative permit and other items, such as the operating room (OR) schedule. Patient identification is achieved by also asking the patient to state his or her full name and birth date. This information is compared with the patient identification bracelet. Documentation of the processes implemented is completed on the designated institutional form or forms.

The surgical site is marked with a permanent nontoxic marking pen. The patient should be involved in this process. A standard policy needs to be developed within the particular facility as to how marking will be accomplished for urologic, endoscopic, and abdominal procedures, particularly when they involve laterality. This mark should be clearly visible following prepping and draping.

Time-out is a pause in the activity that occurs before the start or incision on all procedures. The entire team stops to verbally confirm the patient’s identity, verify the patient’s position, state and agree on the procedure and surgical site, and review that all implants and necessary equipment are available and ready (Patient Safety). The nurse documents this process according to hospital policy.

When medications are used intraoperatively, the containers should always be marked with the medication and dose (refer to Chapter 2 for a full discussion of medication safety). The scrub person, who may be a registered nurse or surgical technologist, verifies the medication and dosage verbally when passing the drug in its administration device to the surgeon. Local anesthetics that contain epinephrine should be used with caution in urology. Many urologic interventions involve “end-organs,” for example, the scrotum, testicles, and penis. The use of epinephrine in these areas can result in an ischemic situation and should be avoided.

Positioning.

Thorough understanding of the urologic OR bed and its functions is essential for optimum patient positioning. The position in which the patient is placed for surgery is determined by the particular operation to be performed. For urologic operative procedures the patient may be placed in the lateral, supine, prone, or lithotomy position. Any of these positions may be exaggerated to give optimum access to the organ involved, particularly in radical surgery of the prostate and bladder. When the patient is supine, his or her arms are placed on padded armboards with the palms up and fingers extended. Armboards are maintained at less than a 90-degree angle to prevent brachial plexus stretch. If there are surgical reasons to tuck the arms at the side, the elbows are padded to protect the ulnar nerve, the palms face inward, and the wrist is maintained in a neutral position (Denholm, 2009). A drape secures the arms. It should be tucked snuggly under the patient, not under the mattress. This prevents the arm from shifting downward intraoperatively and resting against the OR bed rail. Acting as the patient’s advocate, the nurse takes considerable care to ensure that the surgical position does not interfere with respiration or circulation. It is essential to avoid displacement of the joints and undue tension on neurovascular bundles or ligaments. A patient positioned laterally (flank position) for renal surgery has the spine extended for greater access to the retroperitoneal space. Padding and stabilized support with gel pads, pillows, sandbags, and straps should be available for precise anatomic positioning and safety (see Chapter 6). When an electrosurgical unit (ESU) is to be used, care must be taken that the patient does not contact metal parts of the OR bed. In some procedures involving stones of the kidneys or ureters, intraoperative fluoroscopy may be required. When fluoroscopy (C-arm) is to be used, the patient must be placed on an OR bed compatible with its use. Whenever possible, the perioperative nurse takes measures to protect the patient from undue radiation exposure to the thyroid and chest areas by using small leaded shields. In urologic procedures it generally is not feasible to shield the reproductive organs during fluoroscopy.

Aseptic Techniques and Safety Measures.

Prevention of infection is an important nursing goal in the care of the genitourinary patient. It is, however, seldom possible to confirm freedom from infection intraoperatively or immediately postoperatively. Aseptic techniques must be carefully maintained and monitored. Skin preparation and draping procedures (see Chapter 4) vary, depending on the surgery to be performed and institutional protocols. Special care must be taken when cleansing the perineal area to avoid contamination from the rectum to the urethra. Prepping solutions should be applied with downward strokes and the sponge discarded once it has contacted the inner vaginal or anal areas. Transurethral passage of instruments and catheters requires meticulous technique to prevent retrograde infections of the urinary tract, which account for 32% of all healthcare-associated infections (Scott, 2012).

Visualization of the bladder during transurethral procedures is often enhanced by darkening the room. Provision should be made for proper adjustments to lighting. ESUs and fiberoptic light systems are common adjuncts in urologic surgery. The nurse and scrub person must be familiar with the manufacturer’s safety precautions and recommendations during their use.

Use of Irrigating Fluids.

When the bladder is entered, sterile distilled irrigating fluid is administered to distend it for effective visualization. Commercially prepared sterile irrigation solutions with appropriate closed administration sets are highly recommended. Such closed systems prevent the inherent risks of cross-contamination. Large volumes of irrigating solutions are frequently used, particularly during more extensive endoscopic procedures. When these solutions are at the room temperature of the OR, they are cold compared with the patient’s internal body temperature and can cause hypothermia. Solution-warming units are available commercially and are a useful tool to help decrease this risk. The drawback to these units may be that the warmth delays clotting, thus increasing the risk of blood loss.

Commercially prepared sterile irrigation solutions are available in collapsible bags and rigid plastic containers, both of which have the same advantages: neither depends on air, and each may be hung in series, thus providing continuous irrigation without interruption. Air bubbles, a problem that distorts visibility during the procedure, are eliminated with these systems.

For simple observation cystoscopy, retrograde pyelography, and simple bladder tumor fulgurations, sterile distilled water may be used without complication. However, during transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP), venous sinuses may be opened and varying amounts of irrigant are invariably absorbed into the bloodstream. Studies indicate that the use of distilled water during TURP may result in hemolysis of erythrocytes and possible renal failure. Other important complications include dilutional hyponatremia and cardiac decompensation.

Therefore, a clear, nonelectrolytic, and iso-osmotic solution should be used. The most widely used urologic irrigating fluids are 3% sorbitol, an isomer of mannitol, and 1.5% glycine, an aminoacetic acid solution. In dilute solutions, sorbitol and glycine have many properties that make them particularly useful for irrigation during transurethral prostatectomy. At slightly hypotonic concentrations they do not produce hemolysis. However, if too much intravasation occurs with glycine, an encephalitic state can result from the ammonia produced (Surgical Pharmacology). Because the solutions are nonelectrolytic, they do not cause dispersion of high-frequency current with consequent loss of electrosurgical cutting capacity, as occurs with normal saline.

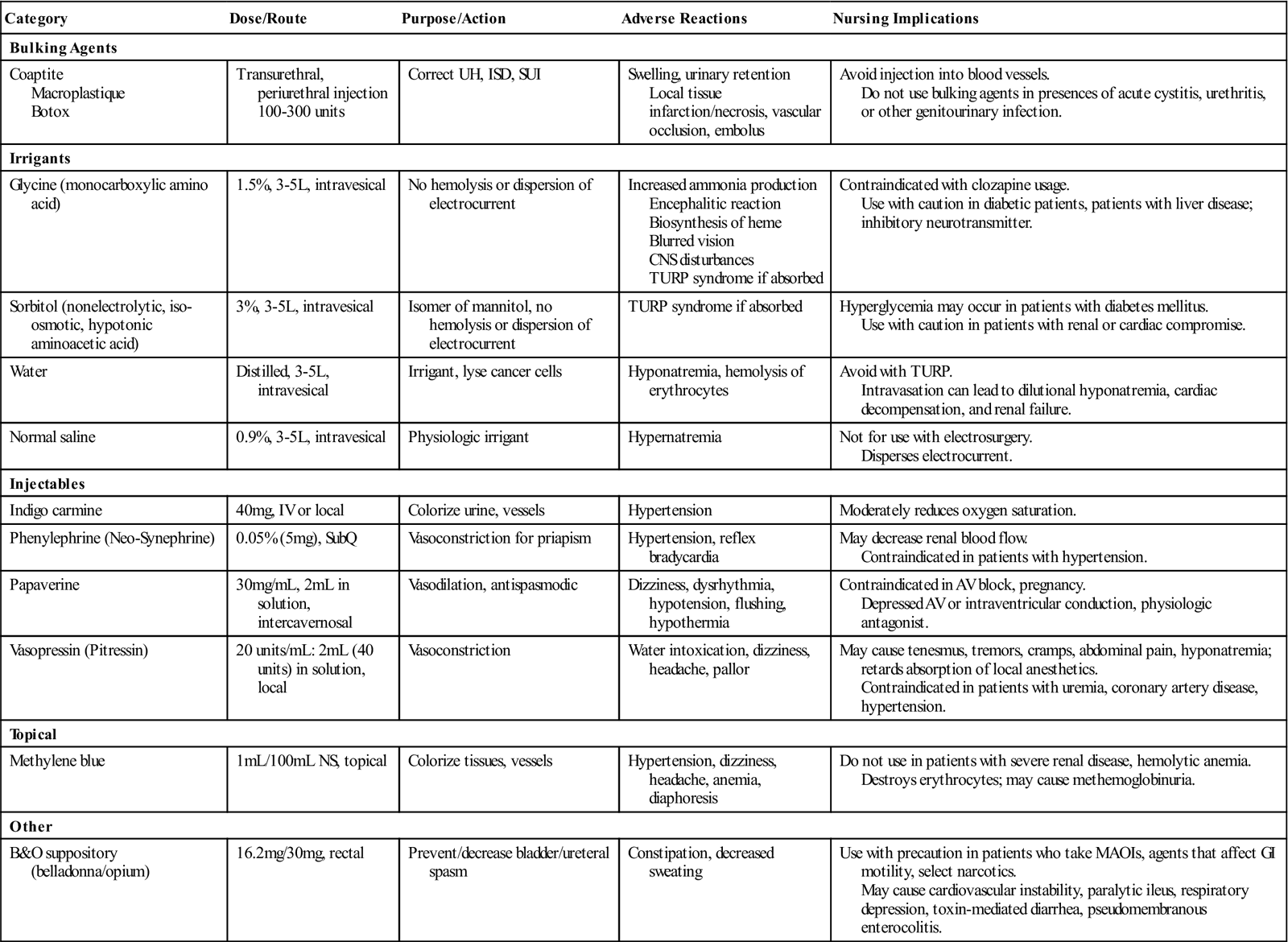

Surgical Pharmacology

Agents Used in Urologic Surgery

| Category | Dose/Route | Purpose/Action | Adverse Reactions | Nursing Implications |

| Bulking Agents | ||||

| Coaptite Macroplastique Botox | Transurethral, periurethral injection 100-300 units | Correct UH, ISD, SUI | Swelling, urinary retention Local tissue infarction/necrosis, vascular occlusion, embolus | Avoid injection into blood vessels. Do not use bulking agents in presences of acute cystitis, urethritis, or other genitourinary infection. |

| Irrigants | ||||

| Glycine (monocarboxylic amino acid) | 1.5%, 3-5 L, intravesical | No hemolysis or dispersion of electrocurrent | Increased ammonia production Encephalitic reaction Biosynthesis of heme Blurred vision CNS disturbances TURP syndrome if absorbed | Contraindicated with clozapine usage. Use with caution in diabetic patients, patients with liver disease; inhibitory neurotransmitter. |

| Sorbitol (nonelectrolytic, iso-osmotic, hypotonic aminoacetic acid) | 3%, 3-5 L, intravesical | Isomer of mannitol, no hemolysis or dispersion of electrocurrent | TURP syndrome if absorbed | Hyperglycemia may occur in patients with diabetes mellitus. Use with caution in patients with renal or cardiac compromise. |

| Water | Distilled, 3-5 L, intravesical | Irrigant, lyse cancer cells | Hyponatremia, hemolysis of erythrocytes | Avoid with TURP. Intravasation can lead to dilutional hyponatremia, cardiac decompensation, and renal failure. |

| Normal saline | 0.9%, 3-5 L, intravesical | Physiologic irrigant | Hypernatremia | Not for use with electrosurgery. Disperses electrocurrent. |

| Injectables | ||||

| Indigo carmine | 40 mg, IV or local | Colorize urine, vessels | Hypertension | Moderately reduces oxygen saturation. |

| Phenylephrine (Neo-Synephrine) | 0.05% (5 mg), SubQ | Vasoconstriction for priapism | Hypertension, reflex bradycardia | May decrease renal blood flow. Contraindicated in patients with hypertension. |

| Papaverine | 30 mg/mL, 2 mL in solution, intercavernosal | Vasodilation, antispasmodic | Dizziness, dysrhythmia, hypotension, flushing, hypothermia | Contraindicated in AV block, pregnancy. Depressed AV or intraventricular conduction, physiologic antagonist. |

| Vasopressin (Pitressin) | 20 units/mL: 2 mL (40 units) in solution, local | Vasoconstriction | Water intoxication, dizziness, headache, pallor | May cause tenesmus, tremors, cramps, abdominal pain, hyponatremia; retards absorption of local anesthetics. Contraindicated in patients with uremia, coronary artery disease, hypertension. |

| Topical | ||||

| Methylene blue | 1 mL/100 mL NS, topical | Colorize tissues, vessels | Hypertension, dizziness, headache, anemia, diaphoresis | Do not use in patients with severe renal disease, hemolytic anemia. Destroys erythrocytes; may cause methemoglobinuria. |

| Other | ||||

| B&O suppository (belladonna/opium) | 16.2 mg/30 mg, rectal | Prevent/decrease bladder/ureteral spasm | Constipation, decreased sweating | Use with precaution in patients who take MAOIs, agents that affect GI motility, select narcotics. May cause cardiovascular instability, paralytic ileus, respiratory depression, toxin-mediated diarrhea, pseudomembranous enterocolitis. |

Modified from Daily Med Current Medication Information, available at http://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/about.cfm. Accessed January 8, 2013; Hodgson BB, Kizior RJ: Saunders nursing drug handbook 2013, St Louis, 2013, Saunders; NCBI PubChem, available at http://pubchem.ncbi.nim.nih.gov. Accessed January 8, 2013.

During ureteropyeloscopy, sterile normal saline is the irrigant of choice unless electrosurgery is to be used. This solution most closely approximates a physiologic solution—an important factor if perforation and extravasation of fluid into the retroperitoneum occur. If electrosurgery is required, as with a TURP, 3% sorbitol or 1.5% glycine should be used.

Thorough knowledge of the potential hazards encountered intraoperatively during transurethral surgery is extremely important. Although complications are more prevalent in the postoperative stage, close observation during the intraoperative period is essential. Signs and symptoms such as sudden restlessness, apprehension, irritability, confusion, nausea, slow pulse rate, seizures, dysrhythmias, and rising blood pressure may be suggestive of TURP syndrome, a severe hyponatremia caused by systemic absorption of irrigating fluid used during surgery (Han and Partin, 2007). Minimum amounts of fluids should be given and urine output carefully monitored. Irrigation fluid should be under as little pressure as possible and the bladder emptied before it reaches full capacity to prevent intravesical pressure. During ureteropyeloscopy it is frequently necessary to use a pressure bag to ensure adequate visualization of the upper urinary tract. Serum electrolyte values should be obtained, and if a low serum sodium value is reported, hypertonic sodium chloride is administered by means of a slow IV drip, often on a volumetric pump. IV diuretics such as furosemide (Lasix) may be required to prevent possible pulmonary edema associated with the administration of hypertonic saline. If the patient’s reaction is severe, surgery may have to be terminated.

Endoscopic and Ancillary Equipment.

Cystoscopic and ancillary equipment often varies from one institution to another. Therefore it is valuable to have a reference manual or standard setup cards that illustrate and describe in detail the required instrumentation for each specific procedure.

The basic cystoscopy tray should include instruments and accessory items that are routinely used for all cystoscopy procedures. If ureteral catheterization is planned, catheterizing telescopes or an Albarrán bridge, which can be packaged and sterilized separately, may be easily added to the basic cystoscopy setup. Instruments for transurethral surgery and other special procedures may be wrapped, sterilized, and placed on separate trays so that they are available on request. This concept minimizes handling of the delicate lensed instruments and ultimately reduces costly repairs.

Cystoscopic procedures frequently require additional instrumentation. Instruments of various types and sizes, such as a visual obturator, biopsy forceps, urethral sounds, Phillips filiforms and followers, and Ellik evacuators, are available as prepackaged, sterile, disposable items. The reusable products may also be packaged separately and sterilized.

Ureteral and Urethral Catheters.

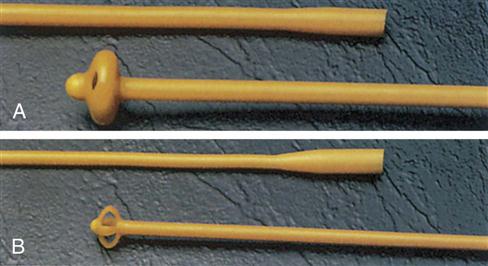

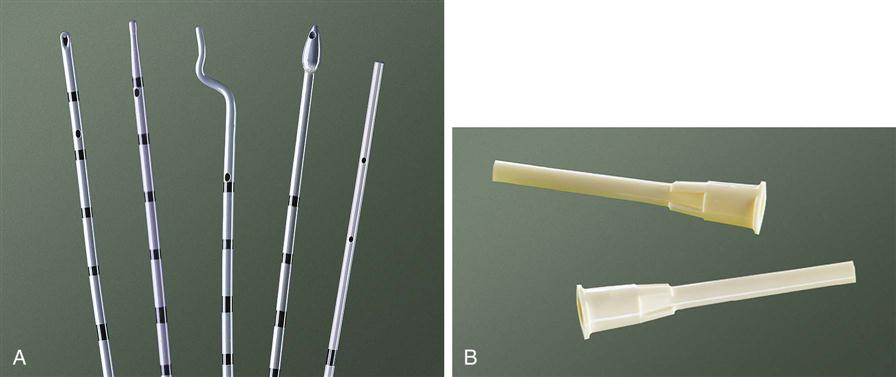

A variety of ureteral and urethral catheters are designed for specific procedures. Ureteral catheters are manufactured of polyurethane material and are graduated so that the surgeon may determine the exact distance the catheter has been inserted into the ureter (Figure 15-8). Most manufacturers provide sterile disposable catheters wrapped in peel-open packages to allow aseptic handling during ureteral insertion. Some indications for the use of ureteral catheters are to (1) perform retrograde pyelography, (2) identify the ureters during pelvic or intestinal surgery, and (3) bypass partial or complete obstruction that may be present as a result of ureteral tumors, calculi, or strictures. Not uncommonly, it is necessary to insert a ureteral stent in a pregnant female because of hydronephrosis or obstructing calculi.

The most commonly used catheters include the open-ended, whistle tip, cone tip, and olive tip. When a retrograde ureterogram is indicated, a cone-tipped ureteral catheter may be helpful in occluding the ureteral orifice to accomplish the x-ray study effectively. When a ureteral catheter is left indwelling, a special adapter (see Figure 15-8, B) may be connected to the end of the ureteral catheter to facilitate connection to a closed urinary drainage system. A small slit may also be created in the Foley catheter, and the distal end of the ureteral catheter can be slipped into it and taped in place.

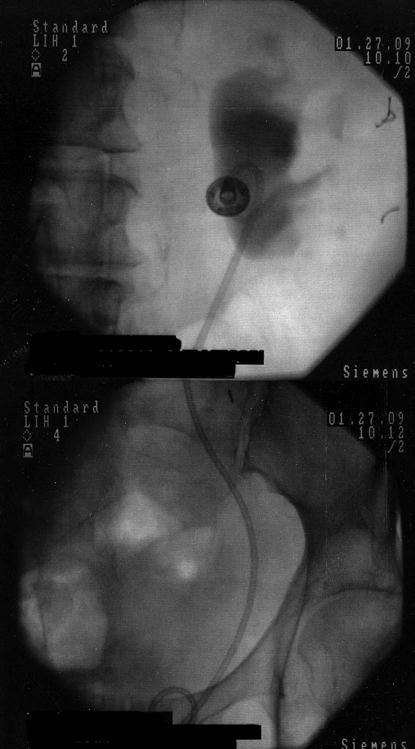

Indwelling double-pigtail or double-J stents are available and are passed cystoscopically to reside within the ureter (Figure 15-9). When the guidewire is removed from the core of the stent, a proximal and distal J or “pigtail” forms in the tubing to retain the stents. Many of these stents have a nonabsorbable suture attached to the distal end, which extends through the urethral meatus. A suture may be easily tied to the distal end of those that do not. The surgeon can then remove the stent in the office setting postoperatively without needing to perform a cystoscopy.

Urethral catheters have a multitude of functions as stents, as drainage tubes, and in diagnostic studies in the OR. They are generally divided into two categories—plain and indwelling (retention)—and range in different French (F) sizes, most commonly 10F through 30F. The Foley catheter is the most frequently used retention catheter and is manufactured with a variety of balloon sizes, tip styles, lengths, and eye arrangements.

After transurethral prostatic surgery a three-way Foley catheter with a 30-mL balloon capacity may be left indwelling. This type of catheter is preferred because it facilitates continuous bladder irrigation (CBI), and the large balloon aids in achieving hemostasis in the prostatic bed. The surgeon may apply light traction on the Foley catheter with a leg strap, adhesive catheter anchor, or tape. This traction causes pressure against the bladder neck and aids in hemostasis. The goal is to prevent traumatic catheter removal in men.

A hematuria catheter, a three-way Foley specifically for patients with excessive clot formation, is also available. This catheter is reinforced with a stretch spiral wire within the catheter lining that permits vigorous aspiration without fear of lumen collapse.

Diagnostic studies performed in the cystoscopy suite may require special catheters for specific studies. A Davis or Trattner triple-lumen double-balloon urethrographic catheter or any of a variety of urodynamic catheters may be used to diagnose lesions of the female urethra, such as urethral strictures, diverticula, and fistulas. To accomplish female urethrography, the catheter is inserted through the urethra into the bladder; the two balloons on the catheter are inflated, one in the bladder and one at the external urethral orifice, effectively isolating the urethra. Contrast medium is injected to visualize the entire urethra.

Another type of self-retaining catheter frequently used in the OR is the Pezzer catheter, also known as a mushroom catheter (Figure 15-10, A). It may be straight or angulated with a large single channel and a preformed tip in the shape of a mushroom. The flexible mushroom tip helps keep the catheter in place. This catheter is used primarily for suprapubic bladder drainage, often for poor-risk patients who have uremia, neurogenic bladder syndrome, or possibly long-standing urinary retention. The catheter is inserted into the bladder through a midline or small transverse abdominal wall incision and secured to the abdomen with suture or tape. The Malecot four-winged catheter, often used as a nephrostomy tube to provide temporary or permanent diversion of urine after kidney surgery and when renal tissue needs to be restored, may also be used for suprapubic drainage (see Figure 15-10, B). A Foley catheter of preferred size is frequently chosen for either purpose. Nephrostomy tube replacement is accomplished by introducing the catheter into the surgical tract with a straight catheter guide and securing it in place with a suture or a nephrostomy retention disk that is one size smaller than the nephrostomy tube being used. The flanges of the disk are taped or sutured to the skin. The use of other variations of urethral catheters is described throughout the chapter.

Photography in Urology.

The use of photographic and video imaging equipment in urologic surgery serves to document the patient’s disease, the progress of a disease process, and long-term follow-up study. It is also an important teaching resource. Video equipment adapts to endoscopic instrumentation and has the capability of projecting an enhanced image on a television monitor, permitting members of the surgical team to observe and learn during the actual surgical procedure. Other visual aids, such as slides and photographs, are used in teaching, as visual references in publication, and as documentation in patient records.

When any form of photography or video imaging is used, the patient’s privacy must be ensured and an informed consent should be obtained. Special release forms should also be signed preoperatively by the patient for any videotapes or photographs to be used in teaching or publications.

Evaluation

Before the patient is taken to the postanesthesia care unit (PACU) or observation unit, the perioperative nurse evaluates the patient’s general condition. The skin is assessed, and bony prominences, prepped and draped areas, and areas contacted by the attachment of ancillary equipment are observed for signs of pressure, irritation, or other changes from the preoperative status.

Many urology patients are discharged to the PACU with catheters and drains inserted, including urethral, ureteral, suprapubic, and wound drains. A local anesthetic may have been used for either primary analgesia or postoperative pain management (preemptive analgesia); preoperative or intraoperative infiltration of the surgical site blocks sensory input, resulting in postoperative analgesia. A hand-off report to the PACU nurse should include intraoperative position, problems encountered specific to the patient, and the patient’s preoperative physical status as well as comprehension and anxiety levels. Documentation of medications administered from the sterile field or by the perioperative nurse intraoperatively should include time of administration, name of medication, dosage, site and route of administration, and the name of the person who performed the application or injection. Drains should be documented as to size and type, insertion site, time and date of insertion, type of collection device, name of the person who performed the insertion, and character of drainage. When several drains are in place, additional labeling on the collection devices is beneficial. Any postoperative observations before or during transport should be recorded. Evaluation should also address whether the patient met the identified outcomes related to specific nursing diagnoses in the perioperative nursing plan of care. Attainment of identified desired outcomes, included in the documentation and report to the PACU, may be phrased as follows:

Patient and Family Education and Discharge Planning

Patient and family education and preparation for discharge allow perioperative nurses to plan for the urologic surgery patient’s care across a continuum. Information is tailored according to the procedure and the patient’s status (Ambulatory Surgery Considerations). Information provided should be presented in language the patient can understand (lay terms) and clarified with the patient by having the patient repeat back in his or her own words the information provided. When possible and with the patient’s approval, family members or others who will serve as caregivers should be included in the educational process at the outset. Institutions may find it helpful to inventory the patient education materials available for select surgical procedures. An example of patient education for home care after nephrectomy is presented in Patient and Family Education on page 473.