A schematic description of the relationship between the cognitive base, professional identity formation, and reflection. The cognitive base of professionalism and professional identity formation should be presented to students on a regular basis throughout the curriculum. Students, residents, and practitioners have an increasing capacity for reflection on professionalism and on their own professional identity as they gain in experiential learning. Stage-appropriate opportunities for reflection should therefore be provided.

(6) Engage students in the development of their own professional identity

Although physicians have been developing professional identities through the ages, until recently it happened in an unplanned and unfocused fashion. As has been stated many times, individuals both consciously and unconsciously pattern their behavior after respected physician role models.32 During the past two decades, the requirement to teach and assess professionalism has moved professionalism into the formal curriculum, and most programs included activities aimed at ensuring that learners understood the norms and values of the medical profession.2,3 The unstated implication was that professionalism was something that was taught by the faculty and learned by students and residents. Shifting the emphasis from teaching professionalism to supporting individuals as they develop their own professional identities represents a major change. The onus is now on individuals wishing to become physicians – joining a community of practice – to actually participate in the process of developing their own professional identities.6–11

It is essential that each student or resident become actively engaged in the wide variety of personal choices, activities, and social interactions that affect the process of socialization. Furthermore, they must remain engaged throughout the continuum of medical education.

The educational implications of this approach have not been explored in depth and there is very little experience documented in the literature. However, we would suggest that learners must first be attracted to the process of identity formation by making it personal.7,8 Interest in the subject should be maintained by introducing activities at an early stage designed to maintain the level of engagement throughout the educational process. We use the schematic representations (Chapter 1, Figures 1.1, 1.4, and 1.5) beginning on the first day of instruction and employing them throughout the continuum of medical education as a means of providing continuity. Students and residents are encouraged to reflect, in a safe space, on the impact of the multiple factors that influence the development of their own identities. Our experience in engaging learners in examining their own identities and their own progress toward a professional identity has been overwhelmingly positive.33 This approach appears to personalize professional identity formation as a group activity.

Engagement can also be facilitated by providing opportunities for learners, along with role models or mentors, to actually trace their own progress toward their desired professional identity. Self-evaluation becomes important because how one regards oneself is fundamental to identity. Thus, simple questions asked on a regular basis such as, “What is your personal or your professional identity or identities?” or, “What factors influenced the development of your professional identity?” can serve as triggers to initiate the reflective process that maintains engagement. Simple scales are available that ask learners to rate their progress toward their professional identity – an exercise that can also lead to reflection.37–39

Finally, engagement can be maintained by stressing the concept of communities of practice and by both encouraging and monitoring the sense of belonging that should develop.

Experience has shown that relationships are of great importance in developing professional identities.6–10 We have assigned many of the activities designed to engage students and maintain that sense of engagement to our mentorship program.33 It has been shown to foster a strong sense of relationship and professional identity in both the students and the mentors. The mentors have been able to observe and support the development of their students’ professional identities. Mentoring also has a profound impact on the mentors, as it forces them to examine their own professional identities, often leading to a reinforced sense of self-understanding and pride.34

(7) Establish membership in a community of practice as an aspirational goal

The collegial nature of medicine has long been understood. It is stressed in the earliest versions of the Hippocratic Oath, and the sense of “belonging” enjoyed by members of the medical profession has been noted by many observers.40–42 Collegiality is thought to foster collaboration within the profession, but it can also result in unfortunate consequences, such as the protection of unethical or incompetent fellow physicians.40 While its presence and power have been noted within the field of medical education, it has rarely been invoked in teaching, and the literature addressing it directly is sparse. In our opinion, the recent adoption of communities of practice as a description of medical practice, and of medical education as a path to joining that practice, builds on and greatly expands the concept of collegiality that has been understood for so long.

Communities of practice are described in many chapters in this book, with expanded material available in Chapters 1 and 5. Communities of practice are formed by people who engage in a process of collective learning, in a shared domain of human endeavor.43,44 Individuals wishing to join the community move from peripheral participation in the community, which is termed “legitimate” because they have an official status. Learners gradually acquire the knowledge and skills, as well as the values and norms, of the community. In the process, they acquire the identity of the community, as well as membership in it. The process takes both time and sustained interaction for relationships within the community to develop.

The community of practice represented by healers has existed since before recorded history, and medicine’s community, along with the communities of the other healing professions, can trace its origins to those times. Thus, the educational community does not have to create a community of practice – it already exists. However, the concept can be invoked as another means of engaging learners in the development of their own professional identities. Our schematic representation shown in Figure 1.1 of Chapter 1 documents this. The idea that students are moving from the periphery of the community to its center parallels the development of their professional identity, something that becomes clear as one notes that the acquisition of the identity of the community is one of the end results of joining the community.44 As is true of professional identity formation, we present our students with the concept of communities of practice on the first day of instruction in medical school and use it, along with identity formation, as we monitor the development of their professional identity.

To our knowledge, there is nothing in the medical education literature that discusses the use of the concept of communities of practice in medical teaching. We believe that the concept has two major advantages. In the first place, it is another means of engaging students and monitoring their own progress. However, of even more significance is the fact that it can be used to engage all members of the community – students, residents, faculty, and even other healthcare professionals – in unifying around a common concept and ideal. Furthermore, a logical consequence of this is that active means can be taken to ensure that the community is welcoming and can foster the movement of learners from the periphery toward the center.43,44 It also offers the opportunity to ensure that this welcome is aimed at all, something that has not been true in the past.45–47 The path to membership in medicine’s community of practice must be equally available to individuals regardless of their race, religion, sexual orientation, nationality, and class.

As pointed out by Ludmerer,29 the impact of postgraduate education on professional identity formation is probably more profound than that of undergraduate education. The sense of joining a community, be it family medicine, orthopedic surgery, psychiatry, or any other discipline, is extremely strong at both the conscious and the unconscious levels. Utilizing this concept to engage residents in participating in the development of their own identities has, in our experience, been very rewarding.

(8) Address the multiple known factors that affect professional identity formation

The schematic representations of professional identity formation and socialization19 that are found in Figures 1.4 and 1.5 in Chapter 1 were developed from the literature in order to aid medical educators to understand the processes and to guide interventions aimed at ensuring that the impact of medical education on identity formation is more predictable and positive. We believe that each factor, or box in the diagrams, should be examined to assess its impact within each academic institution’s culture at both the undergraduate and the postgraduate levels. The objective is to understand the impact of each factor and ensure that its effect on identity formation is positive.

This section will not duplicate the detailed descriptions of the processes of identity formation and socialization and the major factors found in other chapters. However, it is clear that fundamental to encouraging students to actively participate in the development of their own professional identities is reflection6–8,46 (see Figure 8.1). Learners should be encouraged to reflect upon the nature of the identity that they wish to acquire and to recognize the process of negotiating with “self” that takes place as changes are being made to their own identities.6,8 Role models and mentors, as well as the totality of experiences of students and residents, are factors that have a major impact. Time for guided reflection on these experiences must be provided on a regular basis. Not all experiences have a positive impact on a learner’s identity formation, and these experiences must be examined and their impact discussed.46 Every factor included in Figures 1.4 and 1.5 in Chapter 1 has the potential to promote valuable reflection at some stage in the development of a professional identity. As an example, the impact of the healthcare system will be minimal for a first- or second-year medical student, and, consequently, the potential for beneficial reflection is low. However, the closer an individual gets to full participation in medicine’s community of practice, the more relevant such reflection becomes.47 A final-year resident about to enter independent practice will inevitably reflect upon the impact of the healthcare system on his or her identity.

Another example is the role of stress, which should be examined on a regular basis throughout the educational continuum. Learners should be aware of the fact that it is difficult to change an existing identity without some stress. Reflective exercises can assist in coping with the stress.48

As a final example, the satisfaction and joy associated with increased competence should serve as a stimulus to reflection,49–51 again to assist in monitoring progress toward both joining the community of practice and acquiring the professional identity of a physician.

Guided reflection is not carried out in isolation, and the impact of the reflective exercise is not limited to the learner. We have learned that it can have a profound effect on the faculty member or mentor.33 Of necessity, mentors must examine their own identities and their own sense of commitment. The study of our mentorship program indicated a positive impact on the mentors themselves.33

The schematic representations have been useful at both the undergraduate and the postgraduate levels. Our experience and literature indicate that each factor is actually relevant to identity formation at both levels, but the impact varies with the educational level achieved and with the state of development of the identity of each individual student or resident.

(9) Establish an assessment program

As professional identity formation becomes a major educational objective, assessment of progress toward reaching this objective becomes essential (see Chapter 11).

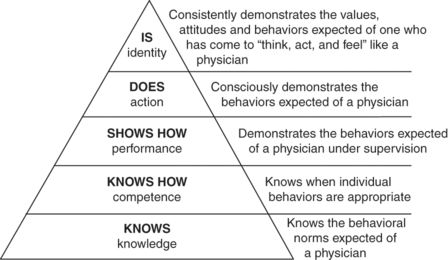

While the assessment of progress toward the development of a professional identity shares some features with the assessment of professionalism, it actually requires a reorientation in our thinking. George Miller, in his classic article, proposed a four-part pyramidal structure as a framework within which the multiple levels of mastery over the art and science of medicine could be assessed.52 Miller’s triangle serves as the basis of Chapter 11. The base of the structure is an assessment of knowledge, knows. The next level of assessment is knows how, followed progressively by shows how and does. Many of the methods used to assess professionalism have been aimed at assessing the level of does. We believe that, given the current state of our knowledge, Miller’s triangle should be expanded.53 A fifth level, is, should be added to indicate that behaviors occur in individuals who have acquired a professional identity because that person must act in that way (see Figure 8.2). They have come to “think, act and feel like a physician.”

The assessment of professionalism is difficult and remains a work in progress. When the educational objective was teaching professionalism and ensuring that the values and attitudes of the profession were understood, programs of assessment were developed around these objectives.54,55 As attitudes and values are difficult to assess, the emphasis shifted to the assessment of observable behaviors that reflect these values and attitudes. To provide reliability and validity, it became clear that multiple assessors using multiple methods was required.55 In addition, it was understood that the assessment of observable behaviors, while providing useful information, missed something, and that some form of narrative assessment by individuals familiar with students and residents was desirable. As is outlined in Chapter 11, this experience will serve as a valuable base when the educational objective is transformed to the support of a professional identity.

However, new approaches will be required, and some will rely upon the self-evaluation of students and residents. How individuals perceive and project themselves is an important component of a personal identity. Therefore, documenting an individual’s perception of his or her own progress toward acquiring a professional identity becomes an invaluable tool.6,8 This progress is nonlinear, occurs in jumps and starts, and is accelerated during times of transition; there are also times of actual regression.6–8 Relatively uncomplicated tools have been developed to assist mentors and faculty members as they work with students to assess progress toward a professional identity. “Learning Logs,”37 “Identity Status Interviews,”37 “Professional Self-Identity Questionnaires,”38 “Professional Role Orientation Inventories,” and “Professional Identity Essays”39 have been reported to be effective in tracing such progress.

It is clear that when professional identity formation is the driving force in medical education, methods of assessment of progress toward that goal that are valid, reliable, and feasible must be developed. The assessment tools that already exist represent a body of knowledge that can be expanded and built upon.

The assessment of professional and unprofessional behaviors will continue to be a priority at all levels of medical education. The impact of formative assessment on learning, including its impact on a learner’s understanding of self, is powerful.31,32 Consequently, we feel safe in predicting that the traditional assessment of professionalism will continue. In addition, medicine does have an obligation to carry out summative assessments to ensure that those entering practice are professional. It is anticipated that the assessment of progress toward the acquisition of a professional identity will take place in parallel with the assessment of professionalism, and that both systems will be compatible and congruent. A benefit of adding the concept of professional identity to assessment is that it introduces identity formation into the remediation process as is outlined in Chapter 12.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree