Data from McIsaac WJ, White D, Tannenbaum D, et al. A clinical score to reduce unnecessary antibiotic use in patients with sore throat. CMAJ 1998;158:75–83.

Diagnostic Testing

- Throat cultures are 90% to 95% sensitive but can take 18 to 24 hours or more to yield results.9,10

- Rapid antigen detection tests (RADTs) can be done at the office and are highly specific (approximately 95%). However, the sensitivity is variable (70% to 95%).9,10

- RADT should be performed in patients with a Centor score of 2 to 3. There is no need for further testing for a Centor score <2.7,9

- Routine use of throat culture for the diagnosis of GAS after a negative RADT is not recommended in adults.9,10

- Antistreptococcal antibody titers are not recommended for routine diagnosis of acute pharyngitis, as they reflect past but not current events.10

TREATMENT

- Treatment of acute viral pharyngitis is supportive.

- The goals of therapy for GAS pharyngitis are to reduce duration and severity of symptoms, to reduce the risk of complications such as rheumatic fever or peritonsillar abscess, and to reduce transmission to close contacts.

- Recommended duration of therapy is 10 days.

- Preferred treatment options include the following:

- Benzathine penicillin G 1.2 million units IM for one dose

- Penicillin V 500 mg PO bid or 250 mg PO four times daily

- Amoxicillin 500 mg PO tid

- Benzathine penicillin G 1.2 million units IM for one dose

- For patients with penicillin allergy, treatment options include cefadroxil or cephalexin (only if allergic reaction is not anaphylaxis), clarithromycin or azithromycin (for 5 days), or clindamycin.

Acute Bronchitis

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

- Acute bronchitis is a self-limited inflammation of the large airways of the lung that is characterized by cough without pneumonia.11

- Viruses account for the majority of cases (>90%) and include influenza, parainfluenza, respiratory syncytial virus, coronavirus, adenovirus, rhinovirus, and human metapneumovirus.

- The role of bacteria in acute bronchitis is unclear, but implicated species include Bordetella pertussis, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, and Chlamydophila pneumoniae. As a group, these agents account for 5% to 10% of uncomplicated acute bronchitis in adults.12

- Of all the etiologic agents that cause acute bronchitis, influenza virus and Bordetella pertussis require special attention because of their morbidity and treatment options.

- For pertussis (whooping cough), universal childhood vaccination is recommended. It has been proven that immunization during childhood wears off over time. Therefore, adults aged 19 to 64 years should receive a single booster administration with Tdap (acellular pertussis vaccine combined with tetanus toxoid and reduced diphtheria toxoid). In addition, adults aged 65 years and older who have not previously received Tdap should receive a single booster administration with Tdap.

DIAGNOSIS

Clinical Presentation

- Patients present with cough lasting more than 5 days, which may be associated with sputum production. Cough may last up to 3 weeks for an episode of acute bronchitis.

- Purulent sputum is common and results from sloughing off of the bronchial epithelium. It is not necessarily an indication of a bacterial rather than a viral infection.

- While evaluating a patient with acute cough, the clinician should be careful in ruling out more serious conditions, such as pneumonia. The presence of abnormal vital signs and abnormal findings on chest examination (e.g., rales, egophony, fremitus) raises concern for pneumonia.

- Pertussis (whooping cough) should be suspected after ≥2 weeks of cough that then becomes paroxysmal (succession of coughs without inspiration), is associated with an inspiratory “whoop” between paroxysms, and may be associated with posttussive emesis. The disease can be mild, and the characteristic “whoop” may be absent in previously immunized patients.

Diagnostic Testing

- Routine sputum cultures are not recommended since bacterial pathogens only play a minor role in acute bronchitis.

- Influenza testing should be considered based on seasonal patterns of influenza and patient presentation.

- Testing for pertussis includes nasopharyngeal culture and polymerase chain reaction (PCR).

- Chest radiography (CXR) is not indicated in the absence of abnormal vital signs or concerning physical exam findings. The exception is cough in the elderly patient, in which pneumonia could have a more subtle presentation.

TREATMENT

- Treatment is largely supportive in patients with acute bronchitis.

- Antivirals for influenza should be considered if influenza infection is confirmed within 24 to 48 hours of onset of symptoms.

- Routine antibiotic treatment of uncomplicated acute bronchitis is not recommended, regardless of duration of cough. Multiple randomized trials have failed to support a significant role for antibiotic therapy in acute bronchitis.11–13

- The one circumstance for which evidence supports antibiotic treatment of uncomplicated acute bronchitis is when there is suspicion of pertussis.12

- Treatment of pertussis can decrease the duration and severity of cough if started within 2 weeks of symptom onset. Treatment is also important to reduce the spread of the infection.

- Treatment regimens for pertussis in adults14:

- Erythromycin 500 mg PO four times daily for 14 days

- Clarithromycin 500 mg PO bid for 7 days

- Azithromycin 500 mg PO once on day 1, followed by 250 mg PO once a day on days 2 to 5

- Erythromycin 500 mg PO four times daily for 14 days

- In case of allergy or intolerance to macrolides, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX) 160 to 800 mg PO bid for 14 days may be used.14

- Postexposure prophylaxis for pertussis is indicated for close contacts within 3 weeks of the onset of cough in the index case. The regimens are the same as for the treatment of pertussis.

Influenza

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

Definition

- Influenza is caused by infection with one of three subtypes of circulating RNA viruses: influenza A, B, or C.

- Influenza C virus causes a mild respiratory illness, and its diagnosis, treatment, and prevention are generally not pursued.

- Two important concepts in influenza pathogenesis are antigenic drift and antigenic shift:

- Antigenic drift:

- Results from point mutations in the envelope glycoproteins (hemagglutinin or neuraminidase) within a strain, which occur season to season

- Can lead to outbreaks of variable extent and severity

- Vaccine changed annually to account for antigenic drift

- Results from point mutations in the envelope glycoproteins (hemagglutinin or neuraminidase) within a strain, which occur season to season

- Antigenic shift:

- Results from complete changes in the hemagglutinin or neuraminidase, creating a new strain (e.g., from H2N2 to H3N2)

- Can lead to epidemics and pandemics

- Results from complete changes in the hemagglutinin or neuraminidase, creating a new strain (e.g., from H2N2 to H3N2)

- Antigenic drift:

- Complications from influenza include primary influenza viral pneumonia, exacerbation of underlying medical conditions (e.g., pulmonary or cardiac disease), secondary bacterial pneumonia (S. pneumoniae, S. aureus, H. influenzae), sinusitis, and otitis media.

Epidemiology

- Influenza is predominantly seasonal with the Northern Hemisphere affected from November to April and the Southern Hemisphere affected May to September.

- Spread from person to person occurs primarily through large-particle respiratory droplet transmission, which requires close contact. Contact with respiratory droplet–contaminated surfaces is another possible source of transmission.

- Certain groups are at increased risk of severe disease or death secondary to influenza virus infection. These groups include elderly persons (age >65), persons with chronic medical conditions, immunocompromised persons, and pregnant women.

Prevention

- The current recommendation for influenza vaccination in the US is for annual administration to patients at least 6 months of age in the absence of contraindications to influenza vaccine.

- Contraindications include previous severe reaction to an influenza vaccination, severe allergy to chicken eggs, history of Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) within 6 weeks following receipt of influenza vaccine, and being moderately or severely ill (with or without fever).

- Following recommendations for influenza vaccination is especially important for high-risk individuals, their close contacts, and health care workers.

- The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) offers annual guidelines for influenza vaccination (http://www.cdc.gov/flu, last accessed December 29, 2014).

DIAGNOSIS

Clinical Presentation

Most patients with influenza exhibit an acute, uncomplicated, self-limiting course, and some may even be asymptomatic. Symptoms may include abrupt onset of fever, headache, myalgia, and malaise, associated with manifestations of an URI.

Diagnostic Testing

- Respiratory specimens for diagnosis should be obtained preferably within 5 days of illness onset, as viral shedding in immunocompetent patients will be substantially decreased after that time.15

- Several diagnostic options are available:

- Viral culture is the gold standard. Results take days to come back. Used for public health surveillance.

- Immunofluorescence: slightly lower sensitivity and specificity than culture, but results available within hours. Performance depends on laboratory expertise.

- RT-PCR: more sensitive than culture. Results available within 4 to 6 hours. Differentiates between types and subtypes.

- Rapid antigen testing: convenient and fast, with results in 10 to 30 minutes. Significantly lower sensitivity than RT-PCR and culture.

- Viral culture is the gold standard. Results take days to come back. Used for public health surveillance.

TREATMENT

- Clinical trials have shown that early antiviral treatment can shorten the duration of symptoms, can shorten the duration of hospitalization, and may reduce the risk of complications from influenza.15,16

- Clinical benefit is stronger if therapy is started within 48 hours of illness onset.15,16

- However, treatment of any person with confirmed or suspected influenza who requires hospitalization is recommended, even if the patient presents >48 hours after illness onset.16

- Adamantanes: amantadine and rimantadine. These are only effective against influenza A. Due to high levels of resistance in the US, CDC no longer recommends its use.16

- Neuraminidase inhibitors: zanamivir and oseltamivir.

- Effective against both influenza A and B

- Oseltamivir: 75 mg PO bid for 5 days

- Zanamivir: two 5-mg inhalations (10 mg total) bid for 5 days

- Effective against both influenza A and B

- Postexposure chemoprophylaxis may be considered in close contacts of a confirmed or suspected case of influenza during that person’s infectious period if those contacts are at high risk for complications of influenza. It should only be used when antivirals can be started within 48 hours of the most recent exposure. Options include

- Oseltamivir: 75 mg PO once a day for 10 days

- Zanamivir: two 5-mg inhalations (10 mg total) once a day for 10 days

- Oseltamivir: 75 mg PO once a day for 10 days

- Influenza viruses and their susceptibility to antiviral medications evolve rapidly. Physicians should keep abreast of patterns of influenza circulation and susceptibility in their communities. Updated information in the US can be found on the CDC website: http://www.cdc.gov/flu (last accessed December 29, 2014).

Community-Acquired Pneumonia

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

Etiology

- Community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) is an infection of the lung parenchyma acquired outside of hospitals or extended-care facilities.

- Bacteria are the most common cause of CAP. The most common pathogens involved are Streptococcus pneumoniae, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenza, and Chlamydophila pneumoniae.

- Less common causes include Legionella spp., Staphylococcus aureus, Enterobacteriaceae, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

- The most common cause of viral CAP in adults is influenza.

Prevention

- Two types of pneumococcal vaccines are approved for use in the US for prevention of noninvasive and invasive pneumococcal infections: pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23) and pneumococcal protein-conjugate vaccine (PCV13).

- PPSV23 is recommended for all adults ≥65 years of age and in persons 19 to 64 years of age who have a condition that increases the risk of pneumococcal disease (including cigarette smoking, chronic lung disease, chronic heart disease, diabetes, among others).

- PCV13 is recommended (in addition to PPSV23) for use in individuals aged 19 or older with functional or anatomic asplenia, immunocompromising conditions, cerebrospinal fluid leaks, cochlear implants, or advanced kidney disease. In late 2014 the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommended PCV13 for all adults ≥65 years.

DIAGNOSIS

Clinical Presentation

- Common symptoms include fever, cough, sputum production, dyspnea, and pleuritic chest pain. Malaise, anorexia, chills, and abdominal complaints are also frequent.

- Clinical features of pneumonia may be lacking or altered in elderly patients. Confusion or delirium could be the initial presentation in the elderly.

- On exam, audible rales may be present. If a consolidation develops, bronchial breath sounds, dullness, egophony, and whispered pectoriloquy are associated findings.

- Tachypnea and hypotension are ominous findings and warrant more rapid evaluation.

Diagnostic Testing

- A CBC often reveals a leukocytosis with a leftward shift.

- A CXR should be obtained in all patients suspected of having pneumonia. The presence of an infiltrate on CXR is diagnostic of pneumonia when clinical features are supportive.

- The radiographic appearance of CAP may include lobar consolidation, interstitial infiltrates, or cavitation.

- Routine testing for microbiologic diagnosis is usually not indicated in the outpatient setting, since most patients do well with empiric antibiotic therapy.

- Exceptions may apply if clinical or epidemiologic clues raise suspicion for specific pathogens that would alter empiric therapy.

- Consider the following tests in selected patients in the appropriate clinical scenario: rapid antigen test for influenza, urinary antigen test for Legionella, urinary antigen test for pneumococcus, and sputum for acid-fast staining.

- Pretreatment sputum Gram stain and culture are useful only when quality specimens can be obtained.

TREATMENT

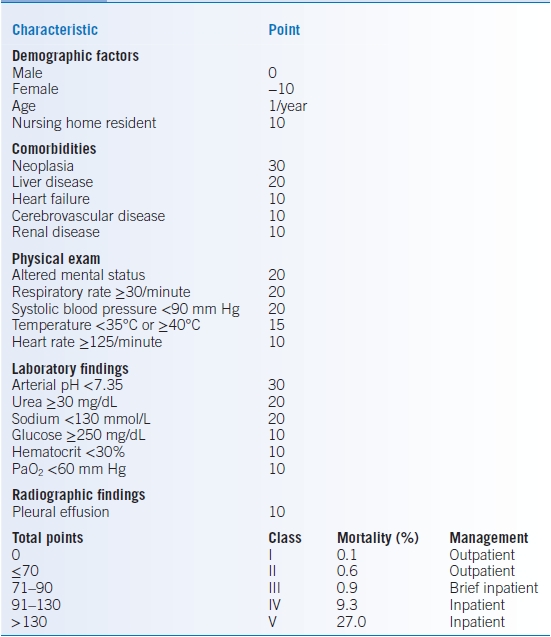

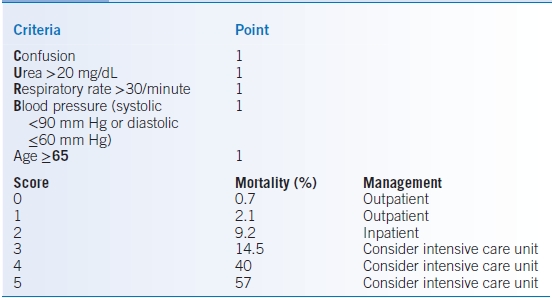

- The decision as to whether the patient can be safely treated as an outpatient or needs admission to the hospital can be assisted by the use of severity-of-illness scores such as the Pneumonia Severity Index (PSI)17 (Table 26-2) or the CURB-65 score18 (Table 26-3).

- Most patients will have a good response to empiric antibiotic therapy; however, treatment should always be tailored to provide narrow coverage if the etiologic agent is known.

- The following are risk factors associated with drug-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae (DRSP): age > 65 years; β-lactam, macrolide, or fluoroquinolone therapy within the last 3 months; alcoholism; medical comorbidities; immunosuppressive therapy or illness; and exposure to a child in a daycare center.

- Comorbidities including chronic heart, lung, liver, or renal disease, diabetes mellitus, malignancy, and asplenia should be taken into account when choosing empiric antibiotic therapy.

- Empiric regimen for previously healthy patients, with no use of antimicrobials within the previous 3 months and with no risk factors for DRSP: macrolide or doxycycline.19

- Empiric regimen for patients with comorbidities, use of antimicrobials within the previous 3 months, or risk factors for DRSP infection19:

- A respiratory fluoroquinolone

- A β-lactam plus a macrolide

- A β-lactam plus doxycycline (less evidence than macrolide combination)

- A respiratory fluoroquinolone

- The following are the suggested oral doses for the abovementioned antimicrobial agents:

- Macrolides: azithromycin, 500 mg on day one followed by 4 days of 250 mg a day; clarithromycin, 500 mg bid; and erythromycin: 250 mg every 6 hours

- Doxycycline: 100 mg bid

- Respiratory fluoroquinolones: levofloxacin, 750 mg daily; moxifloxacin, 400 mg daily; gemifloxacin, 320 mg daily

- β-Lactams: amoxicillin, 1,000 mg tid; amoxicillin-clavulanate, 2,000 mg/125 mg PO bid; cefpodoxime, 200 mg bid; cefuroxime, 500 mg bid

- Macrolides: azithromycin, 500 mg on day one followed by 4 days of 250 mg a day; clarithromycin, 500 mg bid; and erythromycin: 250 mg every 6 hours

- The minimum duration of therapy is 5 days. Patients should be afebrile for 48 to 72 hours and clinically stable before stopping antibiotic therapy.

- Patients with CAP should be appropriately vaccinated for influenza and pneumococcal infection.

- Smoking cessation should be a goal for all patients with CAP who smoke.

TABLE 26-2 Pneumonia Severity Index

Data from Fine MJ, Auble TE, Yealy DM, et al. A prediction rule to identify low-risk patients with community-acquired pneumonia. N Engl J Med 1997;336:243–50.

TABLE 26-3 CURB-65 Score

Data from Lim WS, van der Eerden MM, Laing R, et al. Defining community acquired pneumonia severity on presentation to hospital: an international derivation and validation study. Thorax 2003;58:377–82.

COMPLICATIONS

Complications from CAP include bacteremia with extrapulmonary infection, parapneumonic effusion, empyema, necrotizing pneumonia, and lung abscess.

Tuberculosis

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

- Tuberculosis (TB) is a systemic disease caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. It is one of the most common infectious causes of death worldwide.

- TB most commonly affects the lungs; however, any organ or tissue can be involved. Extrapulmonary TB accounts for 14% to 25% of reported cases globally.20

- TB is transmitted by aerosolized droplets that deposit in the alveoli after inhalation. The bacilli proliferate in the alveolar macrophages and spread to lymph nodes. Subsequent hematogenous dissemination leads to seeding in extrapulmonary locations.

- TB infection can be immediately cleared, lead to primary disease, evolve to latent infection, or reappear as reactivation disease (most common presentation).

- Risk factors associated with TB include malnutrition, immunosuppression (HIV, transplant, tumor necrosis factor [TNF]-α inhibitors), systemic disease (diabetes, renal disease, malignancy), substance abuse, close household contact of a patient with TB, birth in a TB-endemic area, and exposure to crowded settings with poor ventilation.

DIAGNOSIS

Clinical Presentation

- Pulmonary TB most commonly presents with productive cough, which may be accompanied by other respiratory symptoms (shortness of breath, chest pain, hemoptysis) and/or constitutional symptoms (e.g., loss of appetite, weight loss, fever, night sweats, and fatigue).

- Tuberculosis suspect: patient with symptoms or signs suggestive of TB, most commonly an otherwise unexplained productive cough for more than 2 to 3 weeks.

- Definite tuberculosis: patient with Mycobacterium tuberculosis identified from a clinical specimen, either by culture or by a nucleic acid amplification test.

Diagnostic Testing

- Patients meeting clinical and/or epidemiologic criteria for TB should have a CXR. Reactivation TB typically involves focal infiltration of the apical-posterior segments of the upper lobes or the superior segment of the lower lobes.

- All patients with CXR findings suggestive of TB should have sputum specimens (coughed and induced or from bronchoscopy) submitted for microbiologic examination.

- All patients suspected of having pulmonary TB should have at least two, and preferably three, sputum specimens obtained for microscopic examination. When possible, at least one early-morning specimen should be obtained (sputum collected at this time has the highest yield).21

- Acid-fast bacteria observed on stained sputum specimens may represent M. tuberculosis or nontuberculous mycobacteria. Thus, acid-fast staining should be confirmed by culture or molecular testing.

- For all patients suspected of having extrapulmonary TB, appropriate specimens from the suspected sites of involvement should be obtained for microscopy, culture, and histopathologic examination.

- All patients with suspected or confirmed TB should have testing for HIV.

TREATMENT

- Treatment guidelines are available through the World Health Organization (www.who.int) and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) (www.idsociety.org, last accessed December 29, 2014).

- The goals of therapy are eradication of M. tuberculosis infection, preventing TB relapse, preventing development of drug resistance, and preventing TB transmission.

- Treatment should be undertaken with the guidance of an expert and may include hospitalization to initiate therapy, patient education, and respiratory isolation.

- Directly observed therapy (DOT) is considered the standard of care. This allows confirmation of completion of therapy and prevents emergence of drug resistance.

- The local public health authorities should be notified of all cases of TB so that contacts can be identified and arrangements for DOT can be made.

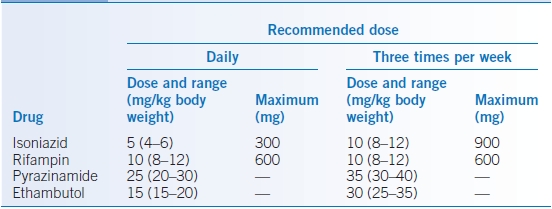

- Initial therapy for tuberculosis should include four drugs: isoniazid (H), rifampin (R), pyrazinamide (Z), and ethambutol (E).

- All TB treatment regimens include an initial intensive phase and a continuation phase. Recommended doses for first-line drugs can be found in Table 26-4.20

- The WHO recommends a standard regimen for new TB patients (presumed, or known, to have drug-susceptible TB) that includes a 2-month initial phase with all four drugs followed by a 4-month continuation phase with isoniazid and rifampicin: 2HRZE/4HR.20

- The optimal dosing frequency for new TB patients is daily throughout the course of therapy. The WHO offers two alternatives to this regimen20:

- Daily intensive phase followed by three times weekly continuation phase [2HRZE/4(HR)3], provided that each dose is directly observed

- Three times weekly dosing throughout therapy [2(HRZE)3/4(HR)3], provided that every dose is directly observed and the patient is not living with HIV or living in an HIV-prevalent setting

- Daily intensive phase followed by three times weekly continuation phase [2HRZE/4(HR)3], provided that each dose is directly observed

- To minimize neurotoxicity, supplemental pyridoxine should be provided (25 to 50 mg daily) in patients taking isoniazid.

- HIV-positive patients should be treated with the same regimens. Some experts recommend prolonged therapy (8 months or more) in certain circumstances. Treatment requires the supervision of an HIV specialist.

- Extrapulmonary TB should be treated with the same regimens as pulmonary TB. However, experts recommend 9 months of therapy for TB of bone and joints and 9 to 12 months of therapy for TB meningitis. In TB meningitis, ethambutol could be replaced by streptomycin.

- Unless drug resistance is suspected, adjuvant corticosteroid treatment is recommended for TB meningitis and pericarditis.

TABLE 26-4 Recommended Doses of First-Line Antituberculosis Drugs for Adults

Data from WHO. Treatment of Tuberculosis: Guidelines, 4th ed. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2010.

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

- Multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB): resistance to at least isoniazid and rifampin.

- Extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis (XDR-TB): resistance to isoniazid, rifampin, and fluoroquinolones, as well as aminoglycosides (amikacin, kanamycin) or capreomycin, or both.

- An assessment of the likelihood of drug resistance should be performed for all patients. The most critical risk factor for MDR-TB is prior TB treatment. Other risk factors include contact with a proven MDR case, patients who remain sputum smear positive at month 2 or 3 of therapy, and HIV infection.

- Treatment of MDR-TB and XDR-TB requires a TB expert.

MONITORING/FOLLOW-UP

- For smear-positive pulmonary TB patients treated with first-line drugs, sputum smear microscopy should be performed at completion of the intensive phase of treatment.

- If the specimen obtained at the end of the intensive phase (month 2) is smear positive, sputum smear microscopy should be repeated at the end of month 3.

- If the specimen obtained at the end of month 3 is smear positive, sputum culture and drug susceptibility testing (DST) should be performed.21

- If the specimen obtained at the end of the intensive phase (month 2) is smear positive, sputum smear microscopy should be repeated at the end of month 3.

- All new pulmonary TB patients who were smear positive at the start of treatment should have sputum specimens for smear microscopy at the end of months 5 and 6.

- Cure: A patient whose sputum smear or culture was positive at the beginning of the treatment but who was smear or culture negative in the last month of treatment and on at least one other occasion.20

- Treatment failure: A patient whose sputum smear or culture is positive at 5 months or later during treatment, or a patient found to harbor a MDR strain at any point during treatment, whether they are smear negative or positive.20 Patients who fail treatment should be managed by a TB expert.

- Follow-up radiographic examinations are usually unnecessary and might be misleading.

Latent Tuberculosis

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection can be contained by host defenses and remain latent. Latent TB infection (LTBI) has the potential to progress to active disease at any time. The lifetime risk of progression is 10%.

DIAGNOSIS

- Latent TB patients are asymptomatic.

- The goal of screening for LTBI is to identify patients at increased risk for developing active TB and who would, therefore, benefit from treatment. These include the following:

- Close contacts of patients with pulmonary TB

- Health care workers and other occupations with exposure to patients with active TB

- Recent immigrants (within 5 years) from high-prevalence countries

- Patients with abnormal CXR with signs of healed TB

- Patients with silicosis, intravenous drug use, diabetes mellitus, HIV, end-stage renal disease, lymphoma, leukemia, and head and neck malignancy

- Patients with transplant, chemotherapy, or other major immunosuppressive conditions

- Treatment with TNF-α inhibitors or systemic glucocorticoids

- Conditions associated with rapid weight loss or chronic malnutrition

- Close contacts of patients with pulmonary TB

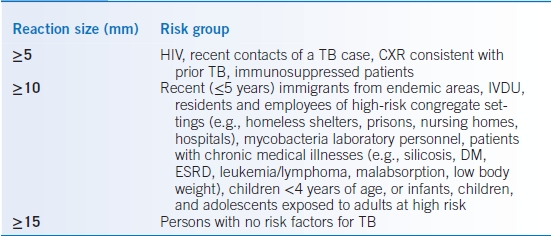

- Screening for LTBI is done by tuberculin skin testing (TST) or by interferon-gamma release assays (IGRAs). A positive screening test without active disease is indicative of LTBI.

- The tuberculin material used for skin testing is purified protein derivative (PPD), injected using the Mantoux technique. The test is interpreted by reading (at 48 to 72 hours) the transverse diameter of the area of induration (not erythema) at the site of injection.

- Interpretation of TST can be found in Table 26-5.22

- Close contacts of patients with active TB with a nonreactive TST should have a repeat test after 10 weeks.

- Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccination in the 1st year of life has been reported to be a source of false-positive results on TST. Of note, BCG vaccination causes no significant effect on TST after 10 years or more. In contrast to TST, IGRAs are not affected by BCG vaccination status.

TABLE 26-5 Tuberculin Skin Test Interpretation

CXR, chest radiograph; IVDU, intravenous drug users; DM, diabetes mellitus; ESRD, end-stage renal disease; TB, tuberculosis.

TREATMENT

- Two regimens are now jointly recommended for the treatment of LTBI by the CDC:22,23:

- Isoniazid 5 mg/kg/day (maximum 300 mg) for 9 months

- Isoniazid 15 mg/kg (maximum 900 mg) plus rifapentine, both given once a week by DOT for 12 weeks

- Isoniazid 5 mg/kg/day (maximum 300 mg) for 9 months

- The isoniazid-rifapentine regimen is only recommended for patients with LTBI aged ≥12 years and who have factors that are predictive of TB developing (e.g., recent exposure to contagious TB, conversion from negative to positive on TST or IGRA, and radiographic findings of healed pulmonary TB). The regimen is not recommended for HIV-positive patients who are receiving antiretroviral therapy.

- The weekly dose of rifapentine according to body weight is 300 mg (10 to 14 kg), 450 mg (14.1 to 25 kg), 600 (25.1 to 32 kg), 750 (32.1 to 49.9 kg), and 900 (≥50 kg).

- Patients taking isoniazid should receive supplemental pyridoxine (25 to 50 mg daily) to minimize neurotoxicity.

- Treatment of LTBI after MDR-TB and XDR-TB exposure is a complex issue and should be undertaken with the guidance of a TB expert.

URINARY TRACT INFECTIONS

Uncomplicated Urinary Tract Infections in Women

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

- Uncomplicated urinary tract infection (UTI) refers to cystitis and pyelonephritis in premenopausal, nonpregnant women with no known urologic abnormalities or comorbidities.

- UTI is the most common bacterial infection encountered in the ambulatory care setting in the US, accounting for 8.6 million visits (84% by women) in 2007. The self-reported annual incidence of UTI in women is 12%.24

- The vast majority of episodes of uncomplicated UTI are caused by Escherichia coli (75% to 95%). Other pathogens include Klebsiella pneumoniae, Staphylococcus saprophyticus, and Proteus mirabilis. Isolation of Enterococcus faecalis, and Streptococcus agalactiae could represent contamination of the urine specimen.

- The pathogenesis involves bacteria from the bowel or the vagina colonizing the periurethral mucosa and ascending through the urethra to the bladder. Pyelonephritis occurs when pathogens ascend to the kidneys through the ureters or, less commonly, when pathogens are seeded by hematogenous spread (e.g., Staphylococcus aureus or M. tuberculosis).

- Risk factors include previous history of UTI, sexual intercourse, use of spermicides, and a history of UTI in a first-degree female relative.

DIAGNOSIS

- Cystitis: symptoms include dysuria, frequency, urgency, suprapubic pain, or hematuria.

- Pyelonephritis: symptoms include fever (>38°C), chills, flank pain, costovertebral angle tenderness, nausea, or vomiting. Symptoms of cystitis may or may not be present.

- A urine dipstick test can detect leukocyte esterase (enzyme released by leukocytes) or nitrite (converted from urinary nitrate by Enterobacteriaceae). The presence of either of these predicts UTI with a sensitivity of 75% and a specificity of 82%.24

- Microscopic examination can be done in a voided midstream urine specimen to detect the presence of pyuria, defined as ≥10 leukocytes/mm3 in uncentrifuged urine or >5 leukocytes/high-power field (HPF) in a centrifuged sediment. Pyuria is present in almost all women with acute cystitis or pyelonephritis.

- Urine cultures can be performed to confirm the presence of bacteriuria and to evaluate the antimicrobial susceptibility of the pathogen involved.

- A urine culture is not necessary for the diagnosis of uncomplicated cystitis, given the reliability of patient symptoms in establishing the diagnosis. The combination of dysuria and frequency without vaginal discharge or irritation raises the probability of cystitis in a woman to more than 90%.25

- A urine culture must be obtained in all patients suspected of having pyelonephritis, and treatment should be adjusted based on antimicrobial susceptibility results. A urine culture is also warranted if symptoms are atypical, if there is failure to respond to initial therapy, or if there is recurrence of symptoms within a month of prior treatment.

- The traditional definition of a positive urine culture is ≥105 colony-forming units (CFUs)/mL together with pyuria, obtained from voided midstream urine. It has been suggested that this criterion is appropriate for pyelonephritis but may lack sensitivity to diagnose cystitis. If culture is indicated for the diagnosis of cystitis, a lower threshold of ≥102 CFU/mL may increase the sensitivity for detection in symptomatic women, with a positive predictive value of 88%.26

TREATMENT

- Treatment guidelines from the IDSA emphasize the importance of considering the ecologic adverse effects of antimicrobial agents when selecting a treatment regimen. These effects include the selection and subsequent colonization or infection with multidrug-resistant organisms.

- Local antimicrobial susceptibility patterns of E. coli should be considered in empiric antimicrobial selection.

- For uncomplicated cystitis, studies suggest a 20% TMP-SMX resistance prevalence as the threshold at which this agent is no longer recommended for empiric treatment.27

- For pyelonephritis, a 10% fluoroquinolone resistance prevalence is the threshold for using an alternative agent in conjunction with or in place of a fluoroquinolone, based on expert opinion.27

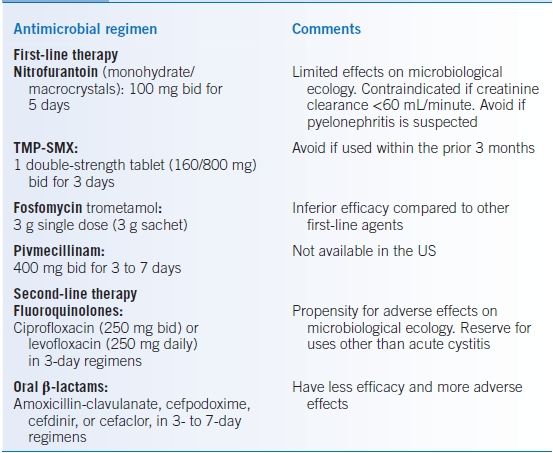

- Empiric therapy of uncomplicated cystitis can be found in Table 26-6.27

- Acute uncomplicated pyelonephritis can be treated in the outpatient setting. However, admission is warranted in severe disease with high fever, pain, marked debility, hemodynamic instability, and poor PO tolerance or if there is concern about compliance with therapy.

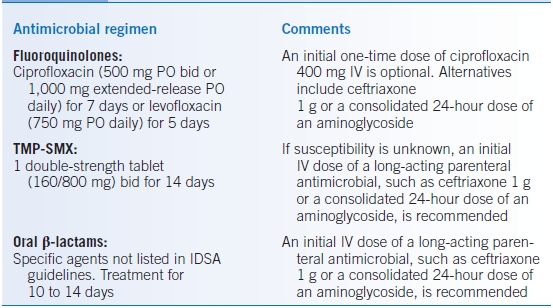

- Empiric therapy of uncomplicated pyelonephritis in the outpatient setting can be found in Table 26-7.27

- Empiric therapy of pyelonephritis requiring inpatient admission should include intravenous antibiotics such as a fluoroquinolone, an aminoglycoside (with or without ampicillin), an extended-spectrum cephalosporin or extended-spectrum penicillin (with or without an aminoglycoside), or a carbapenem. The choice between these agents should be based on local resistance data, and the regimen should be adjusted based on susceptibility results.27

- Follow-up urine cultures are not needed in patients with acute cystitis or pyelonephritis whose symptoms resolve on antibiotics.

- Symptomatic therapy of severe dysuria with phenazopyridine (100 to 200 mg tid) can be considered. Symptoms usually respond to antibiotics within 48 hours.

TABLE 26-6 Empiric Therapy of Uncomplicated Cystitis in Women

TMP-SMX, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.

TABLE 26-7 Outpatient Empiric Therapy of Uncomplicated Pyelonephritis in Women

TMP-SMX, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

- Antimicrobial prophylaxis has been shown to reduce the risk of UTI recurrence by approximately 95% in women who have had three or more UTIs in the past 12 months or two or more UTIs in the past 6 months.24

- Postcoital antimicrobial prophylaxis includes a single dose of nitrofurantoin 50 to 100 mg, TMP-SMX 40/200 mg, or cephalexin 250 mg.

- Continuous antimicrobial prophylaxis includes a daily bedtime dose of nitrofurantoin 50 to 100 mg, TMP-SMX 40/200 mg, or cephalexin 125 to 250 mg. Fosfomycin 3-g sachet every 10 days is also an option.

Uncomplicated Urinary Tract Infections in Men

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

- Uncomplicated UTI refers to cystitis and pyelonephritis in men with no known urologic abnormalities or comorbidities.

- Uncomplicated UTI are much less common in men than in women. This is thought to be due to the greater length and drier surrounding environment of the male urethra, as well as the antibacterial properties of prostatic fluid.28

- The etiologic agents causing uncomplicated UTI in men are similar to those in women. Escherichia coli is the most common causative organism.

- Risk factors include insertive anal intercourse, intercourse with a female partner colonized with uropathogens, and lack of circumcision.28

- In a patient without an obvious risk factor, further evaluation for predisposing conditions (e.g., anatomic abnormalities) should be considered.

- Prostatitis should be suspected in men with recurrent cystitis.

DIAGNOSIS

- Symptoms of uncomplicated cystitis or pyelonephritis in men are similar to those in women.

- The differential diagnosis includes urethritis in sexually active men with genital lesions or urethral discharge, as well as prostatitis in patients with fever, chills, pelvic pain, or obstructive urinary symptoms.

- A urine dipstick test can detect the presence of leukocyte esterase or nitrite. Microscopic examination can be done to detect the presence of pyuria.

- A urine culture must be obtained in all male patients suspected of having an uncomplicated UTI. A positive urine culture is defined as ≥104 CFU/mL, obtained from voided midstream urine.28 A posttreatment urine culture to document urinary tract sterility is recommended in men.

TREATMENT

- Duration of therapy for uncomplicated cystitis should be for a minimum of 7 days.28 Treatment options include TMP-SMX, 1 double-strength tablet (160/800 mg) bid; ciprofloxacin, 500 mg bid; and levofloxacin, 500 mg PO daily.

- Duration of therapy for uncomplicated pyelonephritis should be 10 to 14 days.28 Recommended antimicrobial agents and their doses are the same as the ones described for women. See Table 26-7.

Complicated Urinary Tract Infections

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

- A complicated UTI is the one associated with an underlying condition that increases the risk of infection or of failing therapy.

- Conditions that suggest a potential complicated UTI29:

- Presence of an indwelling urethral catheter, stent, or nephrostomy tube

- Intermittent bladder catheterization

- An obstructive uropathy of any etiology

- Vesicoureteric reflux or other functional abnormalities

- Urinary tract modifications, such as an ileal loop or pouch

- Renal insufficiency and transplantation, diabetes mellitus, and immunodeficiency

- Peri- and postoperative UTI

- Chemical or radiation injuries of the uroepithelium

- Presence of an indwelling urethral catheter, stent, or nephrostomy tube

- Escherichia coli is the most common causative organism. Other pathogens include Proteus mirabilis, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas spp., Serratia spp., Enterococcus, and staphylococci.

DIAGNOSIS

Pyuria and bacteriuria may be absent if the infection does not communicate with the collecting system (i.e., if there is an obstruction). Urine cultures and susceptibility testing should always be obtained prior to therapy.

TREATMENT

- Therapy involves selecting an appropriate antimicrobial regimen and managing the underlying urologic abnormality (when possible).

- Empiric therapy should be based on culture and susceptibility results.

- Complicated cystitis can be managed as an outpatient. However, hospitalization could be required depending on illness severity. Treatment is recommended for 7 to 14 days.

- Patients with complicated pyelonephritis should be initially managed as inpatients. Treatment is recommended for 14 days.

- Recommended initial empiric regimens29:

- Fluoroquinolones: ciprofloxacin or levofloxacin

- Aminopenicillin (amoxicillin or ampicillin) plus β-lactamase inhibitor

- Cephalosporins: cefuroxime, ceftriaxone, and cefotaxime

- Aminoglycoside: gentamicin and tobramycin

- Fluoroquinolones: ciprofloxacin or levofloxacin

- Recommended empiric regimens for severe infection or in case of initial treatment failure (within 1 to 3 days) should include coverage for Pseudomonas spp.29:

- Fluoroquinolones: ciprofloxacin or levofloxacin

- Piperacillin plus β-lactamase inhibitor

- Cephalosporins: ceftazidime, cefepime

- Carbapenem: imipenem, meropenem

- Aminoglycoside plus fluoroquinolone

- Fluoroquinolones: ciprofloxacin or levofloxacin

Asymptomatic Bacteriuria

- Asymptomatic bacteriuria is defined as isolation of a specified quantitative count of bacteria in an appropriately collected urine specimen obtained from a patient without symptoms or signs of UTI.30

- In asymptomatic women:

- Two consecutive voided urine specimens with isolation of the same bacterial strain in quantitative counts ≥105 CFU/mL

or

- A single catheterized urine specimen with one bacterial species isolated in a quantitative count ≥102 CFU/mL

- Two consecutive voided urine specimens with isolation of the same bacterial strain in quantitative counts ≥105 CFU/mL

- In asymptomatic men:

- A single, clean-catch voided urine specimen with one bacterial species isolated in a quantitative count ≥105 CFU/mL

or

- A single catheterized urine specimen with one bacterial species isolated in a quantitative count ≥102 CFU/mL

- A single, clean-catch voided urine specimen with one bacterial species isolated in a quantitative count ≥105 CFU/mL

- Screening for and treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria is only recommended in the following situations30: pregnant women, before transurethral resection of the prostate, and before other urologic procedures for which mucosal bleeding is anticipated.

- Screening for or treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria is not recommended for the following persons: premenopausal nonpregnant women, diabetic women, older persons living in the community, elderly institutionalized subjects, persons with spinal cord injury, and catheterized patients while the catheter remains in situ.

- Antimicrobial treatment of asymptomatic women with catheter-acquired bacteriuria that persists 48 hour after indwelling catheter removal may be considered.

SKIN AND SOFT TISSUE INFECTIONS

Cellulitis and Erysipelas

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

- Cellulitis and erysipelas are skin infections that are not secondary to an underlying suppurative focus, such as abscesses, septic arthritis, or osteomyelitis. However, cellulitis can be associated with purulent drainage or exudates in the absence of a drainable abscess.

- Erysipelas involves the upper dermis and superficial lymphatics, while cellulitis involves the deeper dermis and subcutaneous fat.

- Erysipelas is usually caused by β-hemolytic streptococci, more commonly group A (i.e., S. pyogenes). Groups C and G have also been implicated. Group B streptococci and S. aureus are less frequent.

- Cellulitis without purulent drainage or exudate is more commonly caused by β-hemolytic streptococci. Less frequently, S. aureus (both methicillin-sensitive and methicillin-resistant strains) is the causative agent.

- Cellulitis presenting with purulent drainage or exudate is more commonly caused by community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (CA-MRSA), representing up to 59% of cases presenting to emergency departments in the US.31

- These infections arise when there is disruption of the skin barrier. However, breaches in the skin are not always clinically apparent and may be unnoticed.

- Predisposing conditions include previous cutaneous damage, edema from venous insufficiency or lymphatic obstruction, obesity, or previous cutaneous infection (e.g., impetigo, tinea).32 Diabetes, arterial insufficiency, eczema, and intravenous drug use also predispose to infection.

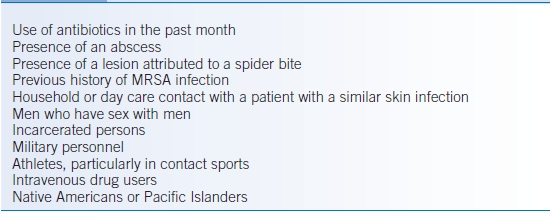

- Risk factors associated with CA-MRSA can be found on Table 26-8.31,33

TABLE 26-8 Risk Factors Associated with Community-Acquired Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (CA-MRSA) Skin and Soft Tissue Infections

DIAGNOSIS

- Both erysipelas and cellulitis present as rapidly spreading areas of erythema, warmth, and edema, sometimes associated with lymphangitis and inflammation of the regional lymph nodes.

- Vesicles, bullae, petechiae, and ecchymoses can be found occasionally.

- The most common site of infection is the lower extremities.

- Erysipelas has the distinctive feature of being a raised lesion with sharply demarcated borders. Cellulitis generally lacks sharp demarcated borders. It can present with or without purulent drainage or exudates, in the absence of a drainable abscess.

- The differential includes contact dermatitis, stasis dermatitis, deep venous thrombosis, acute gout, drug reactions, insect bites, early herpes zoster, and erythema migrans. Physicians must also maintain a high index of suspicion for severe processes such as necrotizing fasciitis, as the initial presentation can be quite benign (see section on necrotizing fasciitis).

- Blood cultures are positive in ≤5% of cases.34 Cultures from needle aspiration of intact skin or from punch biopsies have variable results and are generally not helpful. In the case of cellulitis associated with purulent drainage or exudates, cultures should be obtained to guide therapy.

TREATMENT

- A large proportion of patients can be treated with oral medications. Parenteral therapy is indicated for severely ill patients or for those unable to tolerate oral medications.

- For uncomplicated cellulitis, 5 to 10 days of antibiotic therapy is recommended in the outpatient setting.35 For severe disease, a longer course of antibiotics may be warranted.

- Efforts should be made to treat any underlying predisposing condition.

- Elevation of the affected extremity aids in healing by promoting gravity drainage of the edema and inflammatory substances.

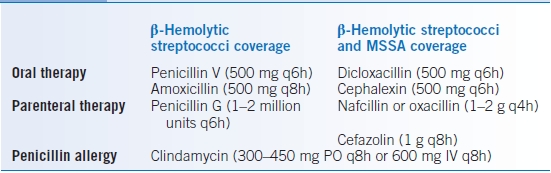

- Erysipelas:

- Therapy should cover β-hemolytic streptococci. Penicillin remains the treatment of choice. Therapeutic options for erysipelas are summarized in Table 26-9.

- If there is high suspicion for methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA) infection, a penicillinase-resistant semisynthetic penicillin or a first-generation cephalosporin should be used.

- Therapy should cover β-hemolytic streptococci. Penicillin remains the treatment of choice. Therapeutic options for erysipelas are summarized in Table 26-9.

- Nonpurulent cellulitis:

- Empiric therapy should cover β-hemolytic streptococci and MSSA.

- Empiric coverage for CA-MRSA is recommended in patients who do not respond to β-lactam therapy, in those with systemic toxicity, or in those with risk factors for CA-MRSA (see Table 26-8).

- Therapeutic options for nonpurulent cellulitis are summarized in Table 26-10.

- Empiric therapy should cover β-hemolytic streptococci and MSSA.

- Purulent cellulitis:

- Empiric therapy should cover CA-MRSA, pending culture results.

- Empiric therapy to cover β-hemolytic streptococci is likely unnecessary.

- If parenteral therapy is needed, vancomycin is the treatment of choice.

- Therapeutic options for purulent cellulitis are summarized in Table 26-11.

- Empiric therapy should cover CA-MRSA, pending culture results.

TABLE 26-9 Empiric Antimicrobial Therapy for Erysipelas

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree