OVERVIEW

- Both functional dyspepsia and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) are very common in primary care and can generally be managed by the GP

- A careful assessment will enable the GP to sort out those patients in whom symptoms may originate from a physical disease, requiring further investigation and/or referral

- Addressing patients’ worries and providing information on symptoms and their management is the cornerstone of the GP’s treatment

- If psychological factors are an important issue (such as coping with stress or anxiety) cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT), or some form of relaxation therapy may be helpful

Introduction

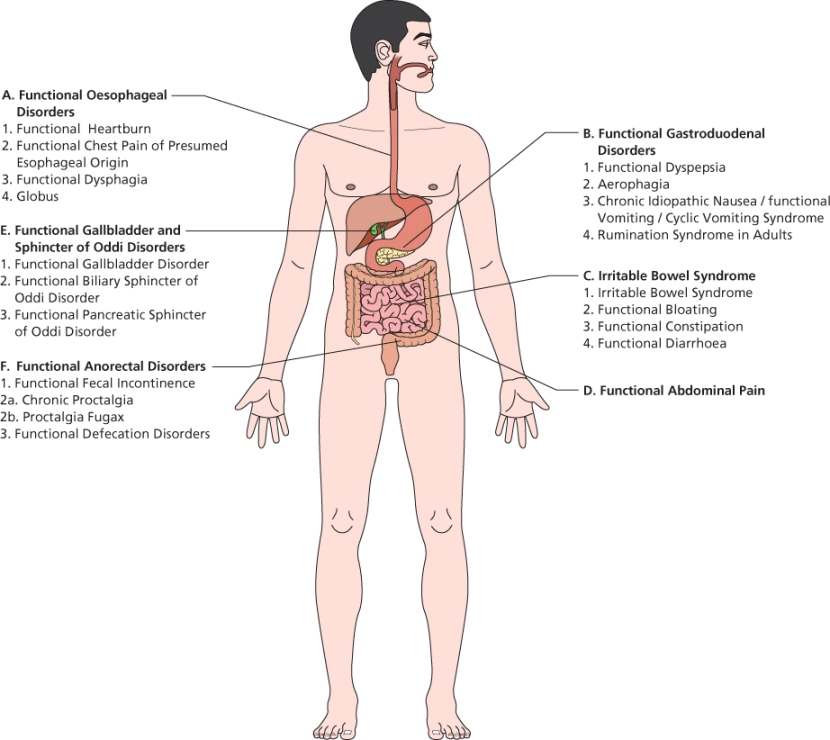

All gastrointestinal symptoms reflect either pain or disturbed function, and in most cases this is not associated with organic disease. The functional gastrointestinal disorders have been exhaustively classified by the Rome Foundation, resulting in diagnostic criteria for a large number of functional gastrointestinal syndromes as shown in Figure 9.1.

The Rome III classification is compatible with a biopsychosocial model of functional gastrointestinal disorders. This is backed up by research into links between the brain and the gut (the so-called ‘brain–gut axis’) alongside changes in immune function and bacterial flora. To date the Rome III criteria have not been validated in primary care, and although they provide a useful framework they are restrictive in that they require symptoms to have been present for more than 6 months, which is often not the case when patients first present in primary care.

Functional dyspepsia

Dyspepsia refers to the experience of pain or discomfort in the upper abdomen. It is often a chronic or relapsing symptom. The Rome III criteria for dyspepsia state that symptoms must have been present for at least the past 3 months and must have started 6 month prior to diagnosis. A prerequisite for the diagnosis of functional dyspepsia, and all function gastrointestinal syndromes is that there is no evidence of an underlying structural disease that is likely to explain the symptoms.

‘Brian’ is a 36-year-old bank employee suffering from intermittent stomach complaints, mainly a burning sensation in his upper abdomen, sometimes with nausea. Gastroscopy 18 months ago was normal, with no evidence of Helicobacter pylori. Until now the episodes only lasted a few weeks at the most, and he coped by using over-the-counter medications. The reason for visiting his GP is that the symptoms are getting worse and have been present for more than a month now. He has stayed at home for a few days last week, because the symptoms were too bothersome although he doesn’t think recent pressure at work is responsible.

Epidemiology in primary care

Dyspepsia affects 20–40% of the people in the UK and accounts for 1.2–4% of all GP consultations. In about half of these consultations the final diagnosis is functional dyspepsia. Most people with dyspepsia do not visit their GP but try to alleviate their symptoms with over-the-counter medication. Depression, anxiety and distress occur more often in patients with functional dyspepsia compared with the general population, and this probably influences their healthcare-seeking behaviour. In most cases the dyspepsia will disappear with or without treatment within months.

GP assessment

The aim of the GP assessment of dyspepsia should be to consider organic disease including peptic ulcer disease, H. pylori infection, reflux disease and cancer and to minimise symptoms. When symptoms persist, and if investigations are negative, the GP should consider a formal diagnosis of functional dyspepsia.

Typical features of functional dyspepsia

There is no pattern of symptoms that reliably predicts functional dyspepsia. Symptoms can be described as any of early fullness; bothersome postprandial fullness; epigastric pain; or epigastric burning, either alone or in combination. Bloating and belching (possibly secondary to air-swallowing) are suggestive but not diagnostic. IBS quite frequently co-occurs with functional dyspepsia and if this is present it may make functional dyspepsia more likely.

Typical features of organic disease

Around 50% of dyspepsia presenting to primary care is functional, which means the other 50% is not! There are several high-quality guidelines on the initial management of dyspepsia such as NICE CG17, which should be followed in the first instance.

History and examination tips

Ask about red flags: vomiting, weight loss, haematemesis, melena, and signs of blockage of food. Also ask for symptoms and a symptom pattern that points to an ulcer or a diaphragmatic hernia. and you should also check for other causes of dyspepsia including medicines (NSAIDs, anticoagulants, steroids, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and over-the-counter medication) and alcohol.

Pay attention to the psychosocial dimensions. Is the patient particularly worried about the symptoms? Is there a possible explanation that has occurred to him? Do his symptoms have any social consequences such as missing any activities?

Although a physical examination rarely identifies positive findings in dyspepsia, it is an essential part of the consultation, indicating that you are taking the patient seriously. A negative investigation does not rule out pathology.

Investigations and referral

The appropriate investigation and management of dyspepsia of recent origin is well described in current guidelines. If the patient has persistent symptoms after a negative H. pylori test and endoscopy then you may need to consider alternative diagnoses. If there are no red flags, and the history is not typical of biliary colic, there is a risk that requesting an ultrasound ‘just to be sure’ may turn up asymptomatic gallstones, which are a common co-incidental finding and may lead to inappropriate surgery with poor outcome.

Explanation

Start by addressing any concerns that the patient has mentioned. Ensure that your explanation is in keeping with the patient’s concerns and deal with these concerns by discussing with the patient why his symptoms do not indicate an underlying disease rather than dismissing it as an unnecessary worry. You can only effectively reassure the patients, if you have taken note of his concerns, and have done all the necessary tests (although this may be limited to a thorough history taking and physical examination).

After having addressed the patient’s worries, explain that these symptoms are common, can be quite bothersome and in all probability do relate to a wide variety of factors. In quite a lot of people the intestines are overly sensitive to all kinds of stimuli such as food, smoking, hormonal changes, medication, stress etc. Both physiological and psychological factors may interact to produce symptoms.

If the patient’s diet includes items that may contribute to the symptoms (fatty foods, alcohol, caffeine) consider reducing these to evaluate the effects. A food diary may be helpful to evaluate the relationship between symptoms and a particular substance. Smoking habits should be addressed because apart from all other consequences, smoking may contribute to dyspepsia symptoms.

Specific treatment

Prescribing an antacid for mild symptoms, or an H2 blocker or proton pump inhibitors (PPI) for more severe symptoms can relieve symptoms. Prescription should be for between 2 and 4 weeks, and then be evaluated. If psychological factors are an important issue (such as coping with stress or anxiety) CBT, or some form of relaxation therapy might be helpful if the patient is motivated for such a therapy. There is no need to persist with long term PPIs in patients with functional dyspepsia.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree