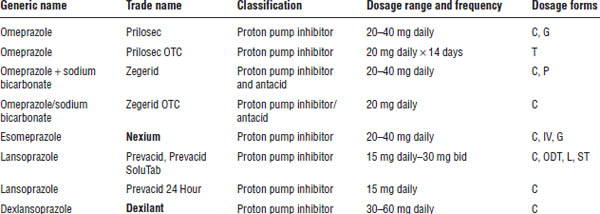

Table 25-1. Selected Medications Used in Treatment of Peptic Ulcer Disease

C, capsule; CT, chewable tablet; EfT, effervescent tablet; G, granules for oral suspension; IV, intravenous; L, liquid; ODT, orally disintegrating tablet; P, powder for oral suspension; ST, SoluTab; T, tablet.

Boldface indicates one of top 100 drugs for 2012 by units sold at retail outlets, www.drugs.com/stats/top100/2012/units.

Tetracycline is best taken on an empty stomach. Antacids, dairy products, or iron-containing products should be taken 2 hours before or after tetracycline.

Sucralfate should be taken 1 hour before meals and at bedtime.

Misoprostol should be taken with or after meals and at bedtime.

Adverse drug effects

■ Side effects occur in 15–20% of patients, but they are usually minor.

■ PPIs and H2RAs are generally well tolerated, but headache, diarrhea, and nausea have been reported.

■ PPIs may increase the risk of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea. Use the lowest effective dose for the shortest treatment duration possible.

■ PPIs may increase incidences of osteoporosis-related fractures of the hip in patients who have at least one additional risk factor for hip fractures. The American College of Gastroenterology Guidelines for the management of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) state that patients with known osteoporosis and no other risk factors for hip fracture may remain on PPI therapy.

■ PPIs may also lower magnesium levels when used chronically. Consider monitoring magnesium levels and using magnesium supplements in patients using PPIs > 3 months.

■ Short-term use of PPIs may increase the risk of community-acquired pneumonia.

■ Antibiotics may cause diarrhea, nausea, dysgeusia, rash, and monilial vaginitis.

■ Bismuth subsalicylate may cause black, tarry stools.

■ Constipation is the most common side effect of sucralfate.

■ Diarrhea occurs in 10–30% of patients taking misoprostol. Abdominal cramping, nausea, flatulence, and headache may also occur.

Drug interactions

■ Omeprazole inhibits the cytochrome P450 (CYP450) 2C19 enzyme, which decreases the elimination of warfarin, phenytoin, and diazepam. Some pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic studies show that concomitant use of omeprazole significantly reduces the ability of clopidogrel to inhibit platelet activity. This could be because clopidogrel is a pro-drug that requires the CYP450 2C19 enzyme to be converted into its active form. Since the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued a warning in 2009 regarding this interaction, subsequent prospective studies have shown that concomitant PPI and clopidogrel therapy does not increase the incidence of cardiovascular events. The 2013 American College of Gastroenterology Guidelines for the Management of GERD state that “PPI therapy does not need to be altered in concomitant clopidogrel users.”

■ Lansoprazole has been reported to increase theophylline clearance by approximately 10%.

■ PPIs and H2RAs may alter the bioavailability of drugs that require an acidic environment for absorption (e.g., ketoconazole, digoxin, iron).

■ Cimetidine is a potent inhibitor of the CYP450 enzyme system, which decreases the elimination of numerous drugs (e.g., warfarin, theophylline, phenytoin).

■ Amoxicillin may decrease the effectiveness of oral contraceptives.

■ Clarithromycin is a potent inhibitor of the CYP450 enzyme system, which decreases the elimination of warfarin, digoxin, cyclosporine, carbamazepine, theophylline, and cisapride (no longer on the market; available for restricted special use only).

■ Tetracycline may decrease the effectiveness of oral contraceptives. Antacids, iron products, and dairy products bind to tetracycline, decreasing its effectiveness. Tetracycline can also increase the therapeutic effect of warfarin. Tetracycline can increase or decrease lithium serum concentrations.

■ Metronidazole produces a disulfiram-like reaction when ingested with alcohol and increases the therapeutic effect of warfarin and lithium.

■ Sucralfate leads to the absorption of small amounts of aluminum, which may accumulate if given to patients with renal insufficiency (especially when combined with aluminum-containing antacids).

■ Sucralfate alters the absorption of numerous drugs, including warfarin, digoxin, phenytoin, ketoconazole, quinidine, and quinolones.

■ Magnesium-containing antacids may increase the GI side effects of misoprostol.

■ Disulfiram-like reactions have been reported with the concurrent ingestion of alcohol and furazolidone.

Monitoring parameters

Patients should monitor for the return of PUD symptoms and for the side effects of medications, as discussed in the earlier sections.

Pharmacokinetics

Several medications are substrates for or have effects on the CYP450 enzyme system in the liver, as discussed in the drug interactions section above.

Nondrug Therapy and Complications

Patients should be counseled to decrease psychological stress and to discontinue drinking alcohol and smoking, taking NSAIDs, and ingesting food or beverages that may exacerbate PUD symptoms.

Major complications (hemorrhage, perforation, penetration, obstruction) occur in approximately 25% of patients with PUD:

■ Patients with active bleeding who are hemodynamically stable should receive intravenous (IV) PPI therapy and undergo endoscopy to evaluate the risk of bleeding recurrence.

■ Patients with active bleeding who are hemodynamically unstable should receive IV fluids and blood transfusions. They should undergo emergency endoscopy for coagulation of bleeding sites. Various modalities may be used to achieve bleeding-site coagulation.

■ As soon as patients tolerate oral intake, IV PPI therapy should be changed to oral therapy.

■ Surgery is reserved for those patients who have refractory ulcers, recurrent bleeding, or a perforated ulcer.

25-5. Definition, Incidence, and Recognition of GERD

The American College of Gastroenterology guidelines state that “GERD should be defined as symptoms or complications resulting from the reflux of gastric contents into the esophagus or beyond, into the oral cavity (including larynx) or lung.” It may be further classified as “the presence of symptoms without erosions on endoscopic examination (non-erosive disease/NERD) or symptoms with erosions (ERD).”

The prevalence of GERD is highest in Western countries, with 10–20% of adults experiencing symptoms weekly. It occurs equally in men and women, except that its incidence is higher in pregnant women. The incidence of GERD is higher and more frequently severe in Caucasians than in African Americans. Obesity has been strongly correlated to the incidence of GERD. GERD may also occur in children. The risk of experiencing complications from GERD increases with age.

Classification

The manifestations of GERD are divided into esophageal and extraesophageal syndromes.

Esophageal syndromes

Esophageal syndromes comprise those that are only symptomatic in nature and those that are symptomatic with esophageal injury on endoscopy. Symptomatic syndromes include the typical reflux syndrome and the reflux chest pain syndrome:

■ The typical reflux syndrome is defined by the presence of troublesome heartburn, regurgitation, or both. Patients may have other symptoms, such as epigastric pain or sleep disturbance.

■ The reflux chest pain syndrome occurs when GERD causes chest pain that is similar to ischemic cardiac pain. This pain can occur without concurrent heartburn or regurgitation.

Symptomatic syndromes with esophageal injury include GERD complications such as reflux esophagitis, reflux stricture, Barrett’s esophagus, and esophageal adenocarcinoma.

■ Reflux esophagitis is characterized by visible breaks in the distal esophageal mucosa.

■ A reflux stricture is defined as a persistent luminal narrowing of the esophagus caused by GERD.

■ Barrett’s esophagus occurs when esophageal squamous epithelium from the gastroesophageal junction is replaced with metaplastic columnar epithelium. It is a risk factor for the development of esophageal adenocarcinoma.

Extraesophageal syndromes

Extraesophageal syndromes include those syndromes that have established associations with GERD and those with proposed associations with GERD.

Esophageal syndromes that have established associations with GERD include reflux cough syndrome, reflux laryngitis syndrome, reflux asthma syndrome, and reflux dental erosion syndrome.

Esophageal syndromes that have proposed associations with GERD include pharyngitis, sinusitis, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, and recurrent otitis media.

Clinical Presentation

Heartburn and regurgitation are the common characteristic symptoms of the typical reflux syndrome. Heartburn is defined as a burning sensation in the retrosternal area. Regurgitation is defined as the perception of flow of refluxed gastric content into the mouth or hypopharynx.

Symptoms usually occur shortly after having a meal, when reclining after a meal, or on lying down at bedtime. Symptoms often awaken patients from sleep.

Symptoms are exacerbated by eating a large meal (especially a high-fat meal), by bending over, and occasionally by exercising.

Symptoms suggestive of complications from GERD (i.e., alarm symptoms) include continuous pain, dysphagia, odynophagia, bleeding, unexplained weight loss, and choking.

Symptom severity does not correlate with the degree of esophagitis present on endoscopy, but severity usually does correlate with the duration of reflux.

Pathophysiology

The effortless movement of gastric contents into the esophagus is a physiologic process that occurs numerous times daily throughout life and does not produce symptoms. It occurs more frequently in patients with GERD.

The pathophysiology of GERD involves the prolonged contact of esophageal epithelium with refluxed gastric contents containing acid and pepsin. Prolonged contact between esophageal epithelium and gastric contents can overwhelm esophageal defense mechanisms and produce symptoms.

Higher-potency gastric refluxate may produce symptoms during times of esophageal contact of normal duration. The presence of refluxate in an esophagus with impaired defense mechanisms may also produce symptoms.

Esophageal defenses consist of the antireflux barrier, luminal clearance mechanisms, and tissue resistance.

■ Components of the antireflux barrier are the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) and the diaphragm. The LES is a thickened ring of circular smooth muscle localized to the distal 2–3 cm of the esophagus. It is contracted at rest, thereby serving as a barrier to refluxate. The diaphragm encircles the LES and acts as a mechanical support, especially during physical exertion.

■ Luminal clearance factors include gravity, esophageal peristalsis, and salivary and esophageal gland secretions (which contain acid-neutralizing bicarbonate).

■ The three areas of tissue resistance are preepithelial, epithelial, and postepithelial defense. Preepithelial and epithelial tissues limit the rate of diffusion of H+ between cell membranes. Postepithelial defense is provided by the blood supply, which removes HCl and supplies oxygen, nutrients, and bicarbonate.

Diagnostic Criteria

For patients who present with typical troublesome symptoms of GERD (e.g., heartburn, regurgitation), a trial of empiric therapy with a PPI is appropriate. A diagnosis of GERD may be assumed for patients who respond to empiric treatment. Nonresponders to PPI therapy should be referred for evaluation.

Diagnostic testing with endoscopy should be performed in patients who present with alarm symptoms and for screening patients at high risk of complications.

■ Endoscopy is the preferred method for evaluating the esophageal mucosa for esophagitis and for evaluating for the presence of complications.

■ Esophageal manometry is not recommended in the initial diagnosis of GERD. It should be used only to assist in the placement of transnasal pH impedance probes or before consideration of antireflux surgery to rule out conditions that would be contraindications to surgery.

■ Ambulatory esophageal reflux monitoring is indicated in patients with nonerosive disease before consideration of surgery or endoscopic therapy, in patients who do not respond to PPI therapy, and in patients in whom the diagnosis of GERD is questionable.

25-6. Treatment Principles and Goals of GERD

Goals of therapy are to alleviate or eliminate symptoms, decrease frequency and duration of reflux, promote healing of the injured mucosa, and prevent the development of complications.

Therapy is aimed at increasing lower esophageal pressure, improving esophageal acid clearance and gastric emptying, protecting esophageal mucosa, decreasing the acidity of refluxate, and decreasing the amount of gastric contents being refluxed.

An 8-week course of once-daily PPI therapy is the treatment of choice for symptom relief and healing of erosive esophagitis in patients with typical symptoms. PPI therapy is associated with increased healing rates and decreased relapse rates of erosive esophagitis compared to H2RAs.

For patients who partially respond to PPI therapy, increasing the dose to twice daily or switching to a different PPI may provide additional symptom relief.

Maintenance PPI therapy should be given to patients who have symptoms when PPIs are discontinued and in patients with complications (e.g., erosive esophagitis, Barrett’s esophagus) at the lowest effective dose. On-demand or intermittent therapy may also be used for maintenance.

H2RA therapy may be used as maintenance therapy in patients without erosive esophagitis if they experience symptom relief.

Bedtime therapy with H2RAs may be added to daytime PPI therapy in patients with objectively confirmed nighttime reflux, but tachyphylaxis may develop after several weeks of use.

Prokinetic therapy with metoclopramide, baclofen, or both should not be used in GERD patients without diagnostic evaluation.

Drug Therapy

Mechanism of action

For information on H2RAs and PPIs, see Section 25-3 on PUD.

Antacids neutralize gastric acid (which increases LES tone) and inhibit the conversion of pepsinogen to pepsin, thus raising the pH of gastric contents. Antacids may be useful for the self-treatment of mild, infrequent heartburn.

Alginic acid reacts with sodium bicarbonate in saliva to form sodium alginate viscous solution, which floats on the surface of gastric contents. The solution acts as a barrier to protect the esophagus from the corrosive effects of gastric reflux.

See Table 25-2 for selected medications.

Patient counseling

For information on H2RAs and PPIs, see Section 25-1 on PUD.

Antacids and alginic acid are appropriate for the initial management of symptoms of GERD that are not troublesome to the patient (e.g., mild, infrequent heartburn). Symptoms persisting longer than 2 weeks require further evaluation and treatment with prescription medications.

Refrigeration of liquid antacids may aid in palatability. Chewable tablets may be more effective than liquids because of increased adherence of antacid and saliva to the distal esophagus. Antacids must be taken at least 2 hours apart from tetracyclines, iron, and digoxin. Antacids and quinolones should be taken 4–6 hours apart.

Alginic acid is effective for the relief of GERD symptoms, but no data indicate esophageal healing on endoscopy. Alginic acid is ineffective if the patient is in the supine position and must not be taken at bedtime.

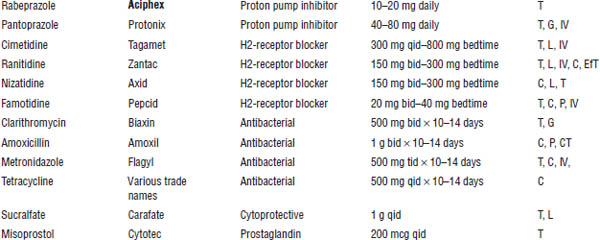

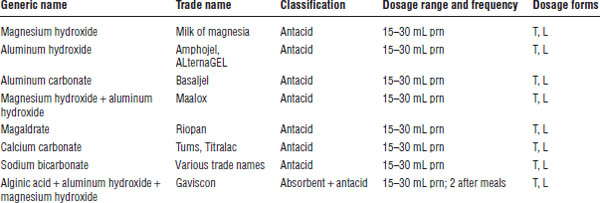

Table 25-2. Selected Antacids and Absorbents

L, liquid; T, tablet.

Adverse drug effects

For information on H2RAs and PPIs, see Section 25-3 on PUD.

Magnesium-containing antacids frequently cause diarrhea. Aluminum-containing antacids frequently cause constipation and bind to phosphate in the gut, which can lead to bone demineralization. Antacids may also cause acid–base disturbances.

Magnesium and aluminum toxicity may occur when used chronically in patients with renal insufficiency. Sodium bicarbonate may cause sodium overload, particularly in patients with hypertension, congestive heart failure, and chronic renal failure. It may also lead to systemic alkalosis. It should be used on a short-term basis, if at all.

Drug interactions

For information on H2RAs and PPIs, see Section 25-3 on PUD.

When taken with antacids, the absorption and effectiveness of tetracycline, ferrous sulfate, and quinolones are reduced because the antacids form chelates with them. Antacids decrease the absorption of azoles and sucralfate by increasing gastric pH. Antacids increase urine pH, which decreases the renal clearance of quinidine. Antacids decrease the systemic absorption of digoxin and H2RAs when taken concomitantly with them. Large doses of antacid may decrease the absorption of phenytoin.

Digoxin and phenytoin serum concentrations should be monitored frequently when antacids are used concomitantly. Suspected adverse effects of antacids should be reported to a health care provider.

Monitoring parameters

Patients should monitor for the return of GERD symptoms and for the side effects of medications as discussed in the previous section.

Pharmacokinetics

Several medications are substrates for or have effects on the CYP450 enzyme system in the liver. See the discussion under drug interactions in Section 25-3.

Nondrug Therapy

■ Weight loss should be recommended for GERD patients who are overweight or have had recent weight gain.

■ Head-of-bed elevation and avoidance of meals 2 to 3 hours before bedtime should be recommended for patients with nocturnal GERD.

■ The routine global elimination of food that may trigger GERD symptoms is not recommended; however, patients should avoid any food or beverage that triggers their own GERD symptoms (e.g., chocolate, caffeine, alcohol, acidic or spicy foods).

■ Calcium channel blockers, β-blockers, nitrates, barbiturates, anticholinergics, and theophylline decrease LES pressure. Tetracyclines, NSAIDs, aspirin, bisphosphonates, iron, quinidine, and potassium chloride have direct irritant effects on the esophageal mucosa. The appropriateness of these drugs in patients with GERD should be evaluated on an individual patient basis.

Surgery is a treatment option for long-term therapy in GERD patients who desire to stop medical therapy, are noncompliant with medical therapy, have adverse effects from medical therapy, or have persistent symptoms caused by refractory GERD.

25-7. Definition, Incidence, and Recognition of Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Idiopathic inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is divided into two major types:

■ Ulcerative colitis is defined as a chronic mucosal inflammatory condition confined to the rectum and colon.

■ Crohn’s disease is defined as a transmural inflammation of the GI tract that can affect any part of the GI tract from mouth to anus.

The incidence of ulcerative colitis is approximately 8–12 per 100,000 persons. The prevalence of Crohn’s disease is approximately 50 cases per 100,000 persons.

In the United States, approximately 500,000 persons have Crohn’s disease and 500,000 persons have ulcerative colitis. Ulcerative colitis is slightly predominant in men; Crohn’s disease is predominant in women. The overall incidence of IBD is similar between men and women.

North America, Northern Europe, and Great Britain have the highest incidence rates for IBD.

Ulcerative colitis typically occurs in persons between 30 and 40 years of age. Crohn’s disease typically occurs between ages 20 and 30. Both may be diagnosed at any stage in life, but of all cases of IBD, 10–15% are diagnosed before adulthood.

The incidence of IBD is low for Hispanics and Asian Americans. Its incidence in African Americans has increased and is equal to that of Caucasians. In addition, its incidence rate is high among the Jewish population in North America, Europe, and Israel.

Classification

The two major types of IBD are ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. Clinical presentation and diagnostic tests help distinguish one form from the other.

Clinical Presentation

IBD is characterized by acute exacerbations of symptoms followed by periods of remission that are spontaneous or secondary to changes in medical therapy or concurrent illnesses.

Ulcerative colitis

The hallmark clinical symptom of ulcerative colitis is bloody diarrhea, which is often accompanied by rectal urgency and tenesmus (straining to empty an already empty bowel associated with pain and cramping).

The extent and severity of ulcerative colitis are determined by clinical and endoscopic findings. Clinical symptoms are categorized as mild, moderate, severe, and fulminant. Endoscopic findings are categorized as distal (limited to below the splenic flexure) or extensive (extending proximal to the splenic flexure).

■ Mild ulcerative colitis is characterized by fewer than four stools per day with or without blood, without systemic disturbance, and with a normal erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR).

■ Moderate ulcerative colitis is characterized by more than four stools per day with minimal signs of toxicity.

■ Severe ulcerative colitis is characterized by more than six stools per day with blood; systemic disturbance (e.g., fever, tachycardia, anemia); and ESR greater than 30.

■ Fulminant ulcerative colitis is characterized by more than 10 bowel movements per day, continuous bleeding, toxicity, abdominal tenderness and distension, blood transfusion requirement, and colonic dilation on abdominal plain films.

Crohn’s disease

The presentation of Crohn’s disease is variable, and its onset is often insidious. Typical symptoms include chronic or nocturnal diarrhea and abdominal pain. Additional typical symptoms include weight loss, fever, and rectal bleeding.

Clinical signs may include pallor, abdominal mass or tenderness, cachexia, perianal fissure, fistula, or abscess.

Extraintestinal symptoms include inflammation of the skin, joints, and eyes.

Symptoms differ depending on the site and severity of inflammation:

■ Mild to moderate Crohn’s disease: Patients are ambulatory and tolerate oral alimentation without dehydration; toxicity (fever, rigors, or prostration); abdominal tenderness; painful mass or obstruction; or weight loss > 10%.

■ Moderate to severe Crohn’s disease: Patients fail to respond to treatment for mild to moderate disease or have fever, weight loss, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting (without obstruction), or anemia.

■ Severe to fulminant Crohn’s disease: Patients have persistent symptoms despite the use of steroids or biologic agents as outpatients, or individuals present with high fever, persistent vomiting, evidence of obstruction, rebound tenderness, cachexia, or abscess.

Symptomatic remission occurs when a patient is asymptomatic or without any symptomatic inflammatory sequelae.

The ileum and colon are the most commonly affected sites. Ileitis may mimic appendicitis. Intestinal obstruction and inflammatory masses or abscesses may also develop. Patients with colonic Crohn’s disease commonly have rectal bleeding, perianal lesions, and extraintestinal manifestations (e.g., spondylarthritis, peripheral arthritis, erythema nodosum, pyoderma gangrenosum, uveitis, fatty liver, chronic active hepatitis, cirrhosis, primary sclerosing cholangitis, gallstones, cholangiocarcinoma, hypercoagulability).

Oral Crohn’s disease is characterized by lesions ranging from a few aphthous ulcers to deep linear ulcers with edema and induration. Gastroduodenal involvement may mimic PUD.

Pathophysiology

The etiology of ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease is unclear, but similar factors may contribute to both diseases. These factors include infectious agents, genetics, environmental factors, psychological factors, and immune factors. Major etiologic theories involve a combination of infectious and immunologic factors.

Ulcerative colitis is confined to the rectum and colon and affects only the mucosa and submucosa. The primary lesion of ulcerative colitis is a crypt abscess, which forms in the crypts of the mucosa. Crohn’s disease most commonly affects the terminal ileum and involves extensive damage to the bowel wall.

Ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease complications can be local or systemic. Local complications of ulcerative colitis include hemorrhoids, anal fissures, and perirectal abscesses. Toxic megacolon can lead to perforation and is a major complication that affects 1–3% of patients with ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease. Colonic strictures and hemorrhage may also occur. Small bowel strictures, obstruction, and fistulae are common in Crohn’s disease. Systemic complications (extraintestinal) can occur with ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease.

Diagnostic Criteria

Ulcerative colitis is diagnosed on the basis of clinical symptoms, proctosigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy, tissue biopsy, and bacteria-negative stool studies. Crohn’s disease is diagnosed on the basis of clinical symptoms, contrast radiography or endoscopy, tissue biopsy, and bacteria-negative stool studies. Abdominal ultrasonography, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging aid in the identification of masses, abscesses, and perianal complications in ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease.

25-8. Treatment Principles and Goals of IBD

Treatment of IBD involves medications that target inflammatory mediators and alter immuno-inflammatory processes. These medications include anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, immunosuppressive, and biologic agents.

Nutritional considerations are also important because many patients with IBD may be malnourished.

Goals of therapy for ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease include induction and maintenance of remission of symptoms, induction and maintenance of mucosal healing, improved quality of life, resolution of complications and systemic symptoms, and prevention of future complications. For patients with Crohn’s disease, remission means that patients are asymptomatic or without inflammatory sequelae, including patients who have responded to medical intervention. Patients who require steroids to maintain their condition are considered steroid dependent, not in remission.

In ulcerative colitis patients, remission is likely to last at least 1 year with medical therapy. Without medical therapy, up to two-thirds of patients will relapse within 9 months. For mild Crohn’s disease, up to 40% of patients improve in 3–4 months with observation alone. Most will remain in remission for prolonged periods without medical therapy.

Mild to moderate distal colitis may be treated with oral aminosalicylates, topical mesalamine, or topical steroids; however, topical mesalamine is superior to topical steroids or oral aminosalicylates.

■ Combining oral and topical aminosalicylates is more effective than using them individually.

■ Patients who do not respond to oral aminosalicylates or topical corticosteroids may respond to mesalamine enemas or suppositories.

■ Patients who are refractory to maximum doses of these agents or have systemic symptoms may require oral prednisone at doses up to 40–60 mg/day or infliximab with an induction regimen of 5 mg/kg at weeks 0, 2, and 6.

■ For the maintenance of remission in patients with proctitis, mesalamine suppositories are effective.

For the maintenance of remission in patients with distal colitis:

■ Mesalamine enemas are effective even if used only every third night. Sulfasalazine, mesalamine compounds, and balsalazide may also be used.

■ The combination of oral and topical mesalamine is more effective than either one used alone.

■ Topical corticosteroids are not effective for maintaining remission in distal colitis.

■ In patients who do not achieve remission using the above therapies, thiopurines and infliximab may be used.

For mild to moderate extensive ulcerative colitis (acute):

■ Initiate therapy with oral sulfasalazine in doses titrated up to 4–6 g/day. Alternatively, a different aminosalicylate in doses up to 4.8 g/day of the active 5–aminosalicylate moiety may be used. Combining oral and topical aminosalicylates may be of additional benefit.

■ Oral steroids should be reserved for patients refractory to oral aminosalicylates in combination with topical therapy or for patients with symptoms severe enough to warrant rapid improvement.

■ Thiopurines are effective for patients refractory to oral steroids with continued moderate disease who do not require acute IV therapy.

■ Infliximab is effective for patients refractory to steroids, patients who are dependent on steroids despite appropriate doses of thiopurines, or patients intolerant to those medications.

For maintenance of remission in mild to moderate extensive ulcerative colitis:

■ Sulfasalazine, olsalazine, mesalamine, and balsalazide are all effective.

■ Chronic steroid therapy should be avoided as much as possible.

■ Thiopurines may be used as steroid-sparing agents for remission not completely sustained by aminosalicylates and sometimes for patients who are steroid-dependent but not acutely ill.

■ Infliximab is effective in maintaining remission in patients who respond to the infliximab induction regimen.

For severe colitis:

■ If urgent hospitalization is not necessary, infliximab 5 mg/kg may be used in patients refractory to maximal oral prednisone, oral aminosalicylates, and topical medications.

■ Patients with incapacitating symptoms require hospitalization and IV steroids. Patients who do not respond to IV steroids within 3 to 5 days should be treated with either IV cyclosporine or infliximab. Patients with fulminant colitis are treated similarly, except that the decision to treat with IV cyclosporine, infliximab, or surgery is made sooner.

■ Adding thiopurines to maintenance therapy significantly enhances long-term remission in severe colitis.

For Crohn’s disease, clinical improvement should be evident within 2–4 weeks. Maximal clinical improvement should occur within 12–16 weeks. Treatment for acute disease should be continued until remission is achieved or the patient’s symptoms fail to improve.

For mild to moderate Crohn’s disease localized to the ileum or right colon, controlled-release oral budesonide is appropriate initial therapy.

■ Controlled-release oral budesonide is more effective than oral mesalamine and placebo. It has similar efficacy to conventional oral corticosteroids.

■ Oral mesalamine has been used as first-line therapy; however, new evidence indicates that it is only minimally more effective than placebo and less effective than corticosteroids.

■ Oral sulfasalazine is more effective than placebo but less effective than corticosteroids for ileocolonic and colonic Crohn’s disease.

■ Rectal aminosalicylates are often used to treat distal colonic Crohn’s disease; however, controlled studies showing efficacy are lacking.

■ Although metronidazole and ciprofloxacin are widely used in the treatment of Crohn’s disease, clinical trials have not consistently demonstrated efficacy.

■ No controlled data exist regarding the treatment of mild to moderate oral Crohn’s disease. Lidocaine lozenges may provide symptomatic relief. Lesions will respond to systemic steroids or azathioprine in 50% of patients.

■ For Crohn’s disease of the stomach, esophagus, duodenum, and jejunum, PPIs, oral corticosteroids, mercaptopurine, azathioprine, methotrexate, infliximab, adalimumab, and certolizumab pegol have improved symptoms in uncontrolled trials.

■ When remission is achieved, maintenance therapy should be initiated. For patients who do not respond, treatment with alternative agents for mild to moderate disease may be initiated or the treatment may be advanced to agents used for moderate to severe disease.

For patients with moderate to severe disease, oral corticosteroids are the mainstay of therapy.

■ Prednisone 40–60 mg daily should be given until symptoms resolve and weight gain resumes. Steroids are not appropriate maintenance therapy.

■ Infections or abscesses should be treated with appropriate antibiotics or surgical drainage.

■ Azathioprine and 6-mercaptopurine may be added to oral corticosteroids to maintain a steroid-induced remission. They are also effective for steroid-dependent or steroid-refractory patients.

■ Parenteral methotrexate is effective for inducing remission and allowing steroid dose reduction in patients with steroid-dependent and steroid-refractory Crohn’s disease.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree