5 Gastrointestinal disease

Symptoms

Dyspepsia and indigestion

Treatment

Treatment is with antacid therapy (Table 5.1).

| Class of drug | Drug | Dose |

|---|---|---|

| H2-receptor antagonists | Cimetidine | 400 mg twice daily |

| Famotidine | 40 mg daily | |

| Nizatidine | 300 mg daily | |

| Ranitidine | 300 mg daily | |

| Proton pump inhibitors | Esomeprazole | 20 mg daily |

| Lansoprazole | 30 mg daily | |

| Omeprazole | 20 mg daily | |

| Pantoprazole | 40 mg daily | |

| Rabeprazole | 20 mg daily | |

| Antacids | Aluminium hydroxide | 10–20 mL 3 times daily |

| Magnesium carbonate | 10 mL 3 times daily | |

| Magnesium trisilicate | 10–20 mL 3 times daily | |

| Aluminium and magnesium complexes | 10 mL between meals and at bedtime | |

| Others | Alginates and antacids | 2 tablets twice daily |

| Chelates and complexes, e.g. tripotassium, dicitratobismuthate, sucralfate | 2 tablets twice daily |

Nausea and vomiting

Treatment

Many patients require no therapy. Food is usually withheld and fluids only are allowed. With more persistent vomiting, IV fluids, e.g. 0.9% saline (p. 369), are given for dehydration and correction of electrolyte abnormalities. A naso-gastric tube is inserted if there is bowel obstruction.

Diarrhoea

Acute diarrhoea

• Treatment

All produce constipation if given frequently.

• Specific therapy

Diarrhoea in patients with HIV infection

Chronic diarrhoea is a common symptom in patients with HIV infection (p. 96). Cryptosporidium is the commonest pathogen isolated. Other infective causes include cytomegalovirus, Mycobacterium avium and Giardia intestinalis. Stool culture with examination for ova, cysts and parasites should be performed, together with flexible sigmoidoscopy/colonoscopy and biopsy.

Chronic diarrhoea

Chronic diarrhoea refers to diarrhoea of more than 4 weeks’ duration. It can be due to a variety of causes (usually non-infective) including inflammation (inflammatory bowel disease), drugs (metformin, statins), functional factors, malabsorption or cancer (change in bowel habit), the treatments for which are described elsewhere.

• Clinical features

Constipation

Treatment

• Laxatives (Box 5.2)

Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease

Reflux is extremely common in the general population, causing mild indigestion and heartburn.

Investigations

Under the age of 45 years, all patients should be treated initially without investigations, unless there are alarm symptoms (Box 5.1).

Treatment

• Medical treatment (Table 5.1)

Non-erosive reflux disease (NERD)

These cases include patients with reflux symptoms. They often do not respond to a PPI. Patients are usually female and often the symptoms are functional (p. 167).

Complications

Other oesophageal disorders

Achalasia

Treatment

Diffuse oesophageal spasm

This disorder causes chest pain and dysphagia, is diagnosed by oesophageal manometry and is characterized by simultaneous non-peristaltic oesophageal contractions occurring after 20% or more swallows. Barium swallow may show a corkscrew appearance. Nutcracker oesophagus is a variant of diffuse oesophageal spasm characterized by very high-amplitude peristalsis (> 200 mmHg).

Chemical oesophagitis

Peptic ulcer disease

Helicobacter pylori

• Non-invasive:

Aspirin and other NSAIDs

Prophylactic therapy

This is necessary for all high-risk patients, i.e. those over 65 years, those with a peptic ulcer history, particularly with complications, and patients on therapy with corticosteroids or anticoagulants. An alternative is to give a COX-2 NSAID, which causes less mucosal damage (p. 298), but long-term cardiovascular risk is a problem.

Complications of peptic ulcer

These include haemorrhage (p. 151).

Gastrointestinal haemorrhage

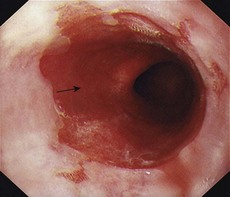

Acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding

Haematemesis is the vomiting of blood from a lesion proximal to the distal duodenum. Melaena is the passage of black tarry stools; the black colour is due to altered blood — 50 mL or more is required to produce this. Melaena can occur with bleeding from any lesion in areas proximal to and including the caecum.

Immediate management (Box 5.3)

Box 5.3 Management of acute gastrointestinal bleeding (see also Fig. 20.4)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree