Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease

KEY CONCEPTS

![]() Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) can be described on the basis of either esophageal symptoms or esophageal tissue injury. The common symptoms include heartburn, acid brash, regurgitation, chest pain, and dysphagia.

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) can be described on the basis of either esophageal symptoms or esophageal tissue injury. The common symptoms include heartburn, acid brash, regurgitation, chest pain, and dysphagia.

![]() Endoscopy is commonly used to evaluate mucosal injury from GERD and to assess for the presence of Barrett’s esophagus or other complications such as bleeding or stricture.

Endoscopy is commonly used to evaluate mucosal injury from GERD and to assess for the presence of Barrett’s esophagus or other complications such as bleeding or stricture.

![]() Ambulatory pH monitoring (with or without impedance monitoring) is useful for confirming acid or nonacid reflux in patients with persistent symptoms without evidence of mucosal damage or for patients with atypical symptoms such as hoarseness of voice, chest pain, persistent cough/throat clearing, or erosion of dental enamel; manometry is useful for patients who are candidates for antireflux surgery and for ensuring proper placement of pH probes.

Ambulatory pH monitoring (with or without impedance monitoring) is useful for confirming acid or nonacid reflux in patients with persistent symptoms without evidence of mucosal damage or for patients with atypical symptoms such as hoarseness of voice, chest pain, persistent cough/throat clearing, or erosion of dental enamel; manometry is useful for patients who are candidates for antireflux surgery and for ensuring proper placement of pH probes.

![]() The goals of GERD treatment are to alleviate symptoms, decrease the frequency of recurrent disease, promote healing of mucosal injury, and prevent complications.

The goals of GERD treatment are to alleviate symptoms, decrease the frequency of recurrent disease, promote healing of mucosal injury, and prevent complications.

![]() GERD treatment is determined by disease severity and includes lifestyle changes and patient-directed therapy, pharmacologic treatment, and antireflux surgery.

GERD treatment is determined by disease severity and includes lifestyle changes and patient-directed therapy, pharmacologic treatment, and antireflux surgery.

![]() Patients with typical GERD symptoms should be treated with lifestyle modifications as appropriate and a trial of empiric acid-suppression therapy. Those who do not respond to empiric therapy or who present with alarm symptoms such as dysphagia, weight loss, anemia, or GI bleeding should undergo endoscopy, or, less commonly, a barium swallow study.

Patients with typical GERD symptoms should be treated with lifestyle modifications as appropriate and a trial of empiric acid-suppression therapy. Those who do not respond to empiric therapy or who present with alarm symptoms such as dysphagia, weight loss, anemia, or GI bleeding should undergo endoscopy, or, less commonly, a barium swallow study.

![]() Surgical intervention is a viable alternative treatment for select patients when long-term pharmacologic management is undesirable or when patients have refractory symptoms or complications.

Surgical intervention is a viable alternative treatment for select patients when long-term pharmacologic management is undesirable or when patients have refractory symptoms or complications.

![]() Acid suppression is the mainstay of GERD treatment. Proton pump inhibitors provide the greatest symptom relief and the highest healing rates, especially for patients with erosive disease or moderate to severe symptoms or with complications.

Acid suppression is the mainstay of GERD treatment. Proton pump inhibitors provide the greatest symptom relief and the highest healing rates, especially for patients with erosive disease or moderate to severe symptoms or with complications.

![]() Many patients with GERD will relapse if medication is withdrawn; so long-term maintenance treatment may be required. A proton pump inhibitor is the drug of choice for maintenance of patients with moderate to severe GERD. Both step-up and step-down therapies have been advocated.

Many patients with GERD will relapse if medication is withdrawn; so long-term maintenance treatment may be required. A proton pump inhibitor is the drug of choice for maintenance of patients with moderate to severe GERD. Both step-up and step-down therapies have been advocated.

![]() Patient medication profiles should be reviewed for drugs that may aggravate GERD. Patients should be monitored for adverse drug reactions and potential drug–drug interactions.

Patient medication profiles should be reviewed for drugs that may aggravate GERD. Patients should be monitored for adverse drug reactions and potential drug–drug interactions.

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a common medical disorder. A consensus definition of GERD states it is “a condition that occurs when the refluxed stomach contents lead to troublesome symptoms and/or complications.”1 The key is that these troublesome symptoms adversely affect the well-being of the patient. Episodic heartburn that is not frequent enough or painful enough to be considered bothersome by the patient is not included in this definition of GERD.1

Esophageal GERD syndromes are classified as either symptom-based or tissue injury–based depending on how the patient presents.1 Symptom-based esophageal GERD syndromes may exist with or without esophageal injury and most commonly present as heartburn, regurgitation, or dysphagia. Less commonly, odynophagia (painful swallowing) or hypersalivation may occur. Tissue injury–based syndromes may exist with or without symptoms. The spectrum of injury includes esophagitis (inflammation of the lining of the esophagus), Barrett’s esophagus (when tissue lining the esophagus is replaced by tissue similar to the lining of the intestine), strictures, and esophageal adenocarcinoma.2 Esophagitis occurs when the esophagus is repeatedly exposed to refluxed gastric contents for prolonged periods of time. This can progress to erosion of the squamous epithelium of the esophagus (erosive esophagitis). Complications of long-term reflux may include the development of strictures, Barrett’s esophagus, or possibly adenocarcinoma of the esophagus.

Gastroesophageal reflux symptoms associated with disease processes in organs other than the esophagus are referred to as extraesophageal reflux syndromes. Patients with extraesophageal reflux syndromes may present with chest pain, hoarseness of voice, chronic cough/throat clearing, or asthma. An association between these syndromes and GERD should only be considered when they occur along with esophageal GERD syndrome because these extraesophageal symptoms are nonspecific and have many other causes.1

Many patients suffering from mild GERD do not go on to develop erosive esophagitis and are often managed with lifestyle changes, antacids, and nonprescription histamine-2 (H2) receptor antagonists or nonprescription proton pump inhibitors. Those with more severe symptoms (with or without tissue injury) predictably follow a course of relapsing disease, requiring more intensive treatment with acid-suppression therapy followed by long-term maintenance therapy. Antireflux surgery offers an alternative for select patients in whom prolonged medical management is undesirable or who have refractory symptoms or complications.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

GERD occurs in people of all ages but is most common in those older than age 40 years. Although mortality is rare, GERD symptoms may have a significant impact on quality of life. The true prevalence of GERD is difficult to assess because many patients do not seek medical treatment, symptoms do not always correlate well with the severity of the disease, and there is no standardized definition or universal gold standard method for diagnosing the disease. However, 10% to 20% of adults in Western countries suffer from GERD symptoms on a weekly basis.3

The prevalence of GERD varies depending on the geographic region but appears highest in Western countries and is on the rise.3

Except during pregnancy, there does not appear to be a major difference in incidence between men and women. Although gender does not generally play a major role in the development of GERD, it is an important factor in the development of Barrett’s esophagus. Alarmingly, adenocarcinoma of the esophagus has increased twofold to sixfold over the past two decades.2 The relationship of adenocarcinoma to Barrett’s esophagus, or even just long-standing GERD, which may be an independent risk factor for esophageal adenocarcinoma, remains to be clearly defined.

Other risk factors and comorbidities that may contribute to the development or worsening of GERD symptoms include family history, obesity, smoking, alcohol consumption, certain medications and foods, respiratory diseases, and reflux chest pain syndrome.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

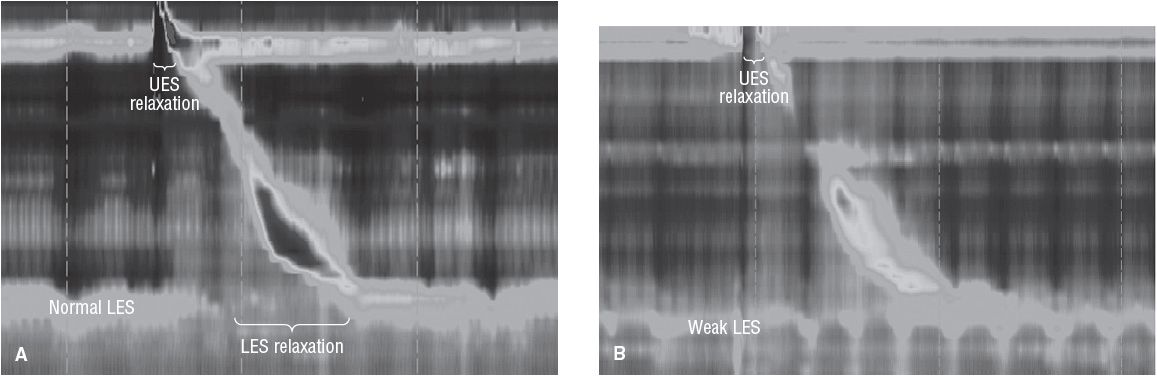

The key factor in the development of GERD is the abnormal reflux of gastric contents from the stomach into the esophagus.4 In some cases, gastroesophageal reflux is associated with defective lower esophageal sphincter (LES) pressure or function (see Fig. 19-1). Patients may have decreased gastroesophageal sphincter pressures related to (a) spontaneous transient LES relaxations, (b) transient increases in intraabdominal pressure, or (c) an atonic LES, all of which may lead to the development of gastroesophageal reflux. Problems with other normal mucosal defense mechanisms, such as abnormal esophageal anatomy, improper esophageal clearance of gastric fluids, reduced mucosal resistance to acid, delayed or ineffective gastric emptying, inadequate production of epidermal growth factor, and reduced salivary buffering of acid, may also contribute to the development of GERD. Substances that may promote esophageal damage on reflux into the esophagus include gastric acid, pepsin, bile acids, and pancreatic enzymes. Thus, the composition and volume of the refluxate, as well as duration of exposure, are important aggressive factors in determining the consequences of gastroesophageal reflux. Rational therapeutic regimens in the treatment of gastroesophageal reflux are designed to maximize normal mucosal defense mechanisms and attenuate the aggressive factors.

FIGURE 19-1 Comparison of a normal esophageal high-resolution manometry showing normal upper esophageal sphincter and lower esophageal sphincter (LES) resting pressure and relaxations with a water bolus (A), compared with that seen in a patient with GERD and a weak resting LES (B).

Lower Esophageal Sphincter Pressure

The LES is a specialized thickening of the smooth muscle lining of the distal esophagus with an elevated basal resting pressure. The sphincter is normally in a tonic, contracted state, preventing the reflux of gastric material from the stomach, but relaxes on swallowing to permit the passage of food into the stomach. Mechanisms by which defective LES pressure may cause gastroesophageal reflux are threefold. First, and probably most importantly, reflux may occur following spontaneous transient LES relaxations that are not associated with swallowing. Although the exact mechanism is unknown, esophageal distension, vomiting, belching, and retching cause relaxation of the LES. While not thought to contribute significantly to erosive esophagitis, these transient relaxations, which are normal postprandially, may play an important role in symptom-based esophageal reflux syndromes. Transient decreases in sphincter pressure are responsible for more than half of the reflux episodes in patients with GERD. The propensity to develop gastroesophageal reflux secondary to transient decreases in LES pressure is probably dependent on numerous factors, including the degree of sphincter relaxation, efficacy of esophageal clearance, patient position (more common in recumbent position), gastric volume, and intragastric pressure. Second, reflux may occur following transient increases in intraabdominal pressure (stress reflux). An increase in intraabdominal pressure such as that occurring during straining, bending over, coughing, eating, or a Valsalva maneuver may overcome a weak LES, and thus may lead to reflux. Third, the LES may be atonic, thus permitting free reflux as seen in patients with scleroderma. Although transient relaxations are more likely to occur when there is normal LES pressure, the latter two mechanisms are more likely to occur when the LES pressure is decreased by such factors as fatty foods, gastric distension, smoking, or certain medications (see Table 19-1).5 Various foods aggravate esophageal reflux by decreasing LES pressure or by precipitating symptomatic reflux by direct mucosal irritation (e.g., spicy foods, orange juice, tomato juice, and coffee). Pregnancy is a condition in which reflux is common. There are many postulated reasons for the increased incidence of heartburn during pregnancy, including hormonal effects on esophageal muscle, LES tone, and physical factors (increased intraabdominal pressure) resulting from an enlarging uterus. A decrease in LES pressure resulting from any of the previously mentioned causes is not always associated with gastroesophageal reflux. Likewise, individuals who experience decreases in sphincter pressures and subsequently reflux do not always develop GERD. The other natural defense mechanisms (anatomic factors, esophageal clearance, mucosal resistance, and other gastric factors) must be evoked to explain this phenomenon.

TABLE 19-1 Foods and Medications That May Worsen GERD Symptoms

Anatomic Factors

Disruption of the normal anatomic barriers by a hiatal hernia (when a portion of the stomach protrudes through the diaphragm into the chest) was once thought to be a primary etiology of gastroesophageal reflux and esophagitis. Now it appears that a more important factor related to the presence or absence of symptoms in patients with hiatal hernia is the LES pressure. Patients with hypotensive LES pressures and large hiatal hernias are more likely to experience gastroesophageal reflux following abrupt increases in intraabdominal pressure compared with patients with a hypotensive LES and no hiatal hernia. Although anatomic factors are still considered significant by some, the diagnosis of hiatal hernia is currently considered a separate entity with which gastroesophageal reflux may simultaneously occur.

Esophageal Clearance

In many patients with GERD, the problem is not that they produce too much acid but that the acid produced ends up in the wrong place and spends too much time in contact with the esophageal mucosa. This is not surprising, because the symptoms and/or severity of damage produced by gastroesophageal reflux are partially dependent on the duration of contact between the gastric contents and the esophageal mucosa. This contact time is, in turn, dependent on the rate at which the esophagus clears the noxious material, as well as the frequency of reflux. The esophagus is cleared by primary peristalsis in response to swallowing, or by secondary peristalsis in response to esophageal distension and gravitational effects. Swallowing contributes to esophageal clearance by increasing salivary flow. Saliva contains bicarbonate that buffers the residual gastric material on the surface of the esophagus. The production of saliva decreases with increasing age, making it more difficult to maintain a neutral intraesophageal pH. Therefore, esophageal damage caused by reflux occurs more often in the elderly, and similarly, for patients with Sjögren’s syndrome or xerostomia. In addition, swallowing is decreased during sleep, making nocturnal GERD a problem in many patients.

Mucosal Resistance

Within the esophageal mucosa and submucosa there are mucus-secreting glands that may contribute to the protection of the esophagus. Bicarbonate moving from the blood to the lumen can neutralize acidic refluxate in the esophagus. When the mucosa is repeatedly exposed to the refluxate in GERD, or if there is a defect in the normal mucosal defenses, hydrogen ions diffuse into the mucosa, leading to the cellular acidification and necrosis that ultimately cause esophagitis. In theory, mucosal resistance may be related not only to esophageal mucus but also to tight epithelial junctions, epithelial cell turnover, nitrogen balance, mucosal blood flow, tissue prostaglandins, and the acid–base status of the tissue. Saliva is also rich in epidermal growth factor, stimulating cell renewal.

Gastric Emptying

Delayed gastric emptying can contribute to gastroesophageal reflux. An increase in gastric volume may increase both the frequency of reflux and the amount of gastric fluid available to be refluxed. Gastric volume is related to the volume of material ingested, rate of gastric secretion, rate of gastric emptying, and amount and frequency of duodenal reflux into the stomach. Factors that increase gastric volume and/or decrease gastric emptying, such as smoking and high-fat meals, are often associated with gastroesophageal reflux. This partially explains the prevalence of postprandial gastroesophageal reflux. Fatty foods may increase postprandial gastroesophageal reflux by increasing gastric volume, delaying the gastric emptying rate, and decreasing the LES pressure. Patients with gastroesophageal reflux, particularly infants, may have a defect in gastric antral motility. The delay in emptying may promote regurgitation of feedings, which might, in turn, contribute to two common complications of GERD in infants (e.g., failure to thrive and pulmonary aspiration).6

Composition of Refluxate

The composition, pH, and volume of the refluxate are important aggressive factors in determining the consequences of gastroesophageal reflux. In animals, acid has two primary effects when it refluxes into the esophagus. First, if the pH of the refluxate is less than 2, esophagitis may develop secondary to protein denaturation. In addition, pepsinogen is activated to pepsin at this pH and may also cause esophagitis. Duodenogastric reflux esophagitis, or “alkaline esophagitis,” refers to esophagitis induced by the reflux of bilious and pancreatic fluid. The term alkaline esophagitis may be a misnomer in that the refluxate may be either weakly alkaline or acidic in nature. An increase in gastric bile concentrations may be caused by duodenogastric reflux as a result of a generalized motility disorder, slower clearance of the refluxate, or after surgery.7 Although bile acids have both a direct irritant effect on the esophageal mucosa and an indirect effect of increasing hydrogen ion permeability of the mucosa, symptoms are more often related to acid reflux than to bile reflux. Specifically, the percentage of time that the esophageal pH is <4 is greater for patients with severe disease as compared with that for patients with mild disease. Esophageal pH monitoring in conjunction with 24-hour bile monitoring has shown a higher incidence of Barrett’s esophagus for patients who have both acid and alkaline reflux.7 More study is needed to substantiate this finding. Nevertheless, the combination of acid, pepsin, and/or bile is a potent refluxate in producing esophageal damage.

Complications

Several complications may occur with gastroesophageal reflux, including esophagitis, esophageal strictures, Barrett’s esophagus, and esophageal adenocarcinoma. Strictures are common in the distal esophagus and are generally 1 to 2 cm in length. The use of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs or aspirin is an additional risk factor that may contribute to the development or worsening of GERD complications.3 Although GERD may lead to esophageal bleeding, the blood loss is usually chronic and low grade in nature, but anemia may occur. In some patients, the reparative process leads to the replacement of the squamous epithelial lining of the esophagus by specialized columnar-type epithelium (Barrett’s esophagus), which increases the incidence of esophageal strictures by as much as 30%. Barrett’s esophagus is most prevalent in white males in Western countries. The risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma may be higher for patients with Barrett’s esophagus as compared with that for the general population, although not as high as previously thought. The absolute annual risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma was 0.12% in those with Barrett’s esophagus.8 The pathophysiology of gastroesophageal reflux is a complex cyclic process. It is difficult, if not impossible, to determine which occurs first: gastroesophageal reflux leading to defective peristalsis with delayed clearing or an incompetent LES pressure leading to gastroesophageal reflux. Understanding the factors associated with the development of GERD provides insight into the treatment modalities currently used to manage patients suffering from this disease.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

![]() GERD can be described on the basis of either esophageal symptoms or esophageal tissue injury. The severity of the symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux does not always correlate with the degree of esophageal tissue injury, but it does correlate with the duration of reflux. Patients with symptom-based esophageal syndromes may have symptoms as severe as those with esophageal tissue injury. It is important to distinguish GERD symptoms from those of other diseases, especially when chest pain or pulmonary symptoms are present.9

GERD can be described on the basis of either esophageal symptoms or esophageal tissue injury. The severity of the symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux does not always correlate with the degree of esophageal tissue injury, but it does correlate with the duration of reflux. Patients with symptom-based esophageal syndromes may have symptoms as severe as those with esophageal tissue injury. It is important to distinguish GERD symptoms from those of other diseases, especially when chest pain or pulmonary symptoms are present.9

CLINICAL PRESENTATION GERD2

Diagnostic Tests

The most useful tool in the diagnosis of gastroesophageal reflux is the clinical history, including presenting symptoms and associated risk factors. Patients presenting with typical symptoms of reflux, such as heartburn or regurgitation, do not usually require invasive esophageal evaluation. These patients generally benefit from an initial empiric trial of acid-suppression therapy. A clinical diagnosis of GERD can be assumed in patients who respond to appropriate therapy.4 Further diagnostic evaluation is useful to prevent misdiagnosis, identify complications, and assess treatment failures.2 Diagnostic tests should be performed in those patients who do not respond to therapy and in those who present with alarm symptoms (e.g., dysphagia, odynophagia, weight loss), which may be more indicative of complicated disease.

Useful tests in diagnosing GERD include upper endoscopy, ambulatory pH monitoring test or impedance monitoring, and manometry. ![]() Endoscopy is commonly used to evaluate mucosal injury from GERD and to assess other complications, such as bleeding or stricture. A camera-containing capsule swallowed by the patient offers the newest technology for visualizing the esophageal mucosa via endoscopy. The PillCam ESO is less invasive than traditional endoscopy and takes less than 15 minutes to perform in the clinician’s office. Images of the esophagus are downloaded through sensors placed on the patient’s chest that are connected to a data collector. The camera-containing capsule is later eliminated in the stool. The main disadvantage of the PillCam is that biopsies cannot be obtained. Of note, it is not recommended to use endoscopy as a “screening tool” for Barrett’s esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma just because a patient has long-standing GERD.1

Endoscopy is commonly used to evaluate mucosal injury from GERD and to assess other complications, such as bleeding or stricture. A camera-containing capsule swallowed by the patient offers the newest technology for visualizing the esophageal mucosa via endoscopy. The PillCam ESO is less invasive than traditional endoscopy and takes less than 15 minutes to perform in the clinician’s office. Images of the esophagus are downloaded through sensors placed on the patient’s chest that are connected to a data collector. The camera-containing capsule is later eliminated in the stool. The main disadvantage of the PillCam is that biopsies cannot be obtained. Of note, it is not recommended to use endoscopy as a “screening tool” for Barrett’s esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma just because a patient has long-standing GERD.1