Functional Bowel Disorders

Michael R.B. Keighley

Incontinence

Incontinence of feces is a demoralizing and psychologically devastating condition for the patient. It is far worse in terms of quality of life than incontinence of urine. So distressing is the condition that many patients afflicted by incontinence of feces never admit their problem to their families or closest medical attendants. Symptoms are therefore concealed, because patients feel ashamed that they are “dirty,” with the inevitable consequence that they become social outcasts with loss of self-esteem, demoralization, and loss of confidence.

Fecal incontinence, without awareness, passive incontinence is the most distressing symptom, necessitating protective clothing and diapers. There is loss of anorectal sensation and motor function.

With urge incontinence, patients have to rush to the bathroom. Hence, sensory awareness is retained, but motor control is only capable of preventing involuntary defecation for a short time. These patients fear traveling or moving out of social circumstances in which a bathroom is not available. Urgency is a common symptom in patients with rectal disease, particularly proctitis or a narrowed rectum, as well as after obstetric trauma.

Soiling is caused by the inability of the anal canal to close completely. Sensation is preserved, and there is a gutter defect in the anal canal through which feces may seep.

Overflow incontinence is caused by fecal impaction. Liquid feces leak around a solid bolus of fecal material that occupies the entire lumen of the rectum. Overflow incontinence is often associated with the aging process; megacolon is associated with loss of sensory awareness in the rectum.

Clinical Presentation

Clinical presentation usually identifies the principal cause for incontinence. Women are affected far more commonly than men are, because obstetric injury is the most common cause of incontinence requiring surgical treatment. Some patients become incontinent after operations on the anal canal or on the rectum and colon. A further group includes patients who sustain trauma to the perineum. Any patient presenting with fecal incontinence should be closely questioned to exclude underlying neurologic disorders, particularly demyelinating disease in the young and cauda equina lesions at all ages. There is also a group of patients with congenital disease who present with incontinence. In such patients, there is usually a history of surgical treatment in the neonatal period for anorectal agenesis, Hirschsprung disease, meningocele, or other congenital lesions affecting the cauda equina or anorectum. Finally, 70% of patients with a rectal prolapse are incontinent; hence, prolapse must be excluded in all patients with symptoms of incontinence.

Causes

Factors Responsible for Normal Continence

Normal continence depends on a number of correlated factors that, in principle, include a reservoir, an anorectal junction that opens and closes at will, and a closed anal canal at rest.

The rectal reservoir may be compromised in patients with inflammatory disease affecting the rectal mucosa and the wall of the rectum, as in ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. The capacity of the rectal ampulla may be severely compromised in patients who have had previous radiation treatment or may have been surgically reduced in patients having ileoanal or coloanal anastomoses, particularly where no reservoir has been constructed. The voluntary control mechanism for opening and closing the anal canal consists of the pelvic diaphragm and puborectalis sling, particularly, as well as the striated external anal sphincter. These muscles may be damaged from trauma after obstructed vaginal deliveries. They may become neuropathic from prolonged second stage of labor, and they may be traumatized by the fetal head or if an episiotomy extends through the sphincters. The striated muscle may fail to function if there has been severe infection resulting in fibrosis around the sphincters or pelvic floor, or the external sphincters may have been divided during anal operations, particularly fistulotomy, or by perineal trauma.

The anal canal is normally closed at rest. This depends on the involuntary contraction of the circular smooth muscle around the anal canal and the integrity of unscarred anus. The internal sphincter is under autonomic control mediated through nitric oxide. The smooth muscle itself may be damaged by previous surgery, such as hemorrhoidectomy, anal dilation, or sphincterotomy. It may become neuropathic from operations that interrupt the normal intermyenteric fibers innervating the internal sphincter, and it may be defective in patients in whom normal chemical transmitters no longer function, as, for instance, in Hirschsprung disease.

The anorectum cannot function normally if it does not receive afferent signals. Thus, patients with impairment of rectal or anal sensation have compromised continence. The sensory fibers of the pudendal nerve supply the anorectum, and this nerve may be damaged after obstetric trauma and in cauda equina lesions. Cerebral degeneration from any cause may result in impaired rectal evacuation and incontinence.

Causes of Incontinence

Obstetric trauma may result in disruption of the fibers of the puborectalis and pelvic floor, a neuropathic injury affecting the pudendal nerve, division of the internal or external anal sphincter, or fibrosis encasing the sphincters following sepsis or repeated operations. Patients may have impairment of rectal evacuation urgency, urge incontinence, soiling, and lack of flatus control.

Postoperative incontinence may be a result of damage to the internal or external anal sphincter after operations on the anus, such as hemorrhoidectomy, sphincterotomy, anal dilation, and anorectal fistula surgery. In some cases, the sphincter muscles may be divided. In others, a gutter deformity may develop in the anal canal, which prevents the anal canal from remaining closed at rest. Colorectal operations may also result in incontinence if they cause rectal strictures or fibrosis of the reservoir, which then is no longer compliant and is small in volume capacity. Incontinence may develop after transection of the low rectum or anal canal as a result of interruption of the intermyenteric autonomic nerve plexus. Thus, any operation on the colon and rectum, particularly if it involves a low anastomosis, may result in impaired continence.

Perineal trauma may result in damage to the sphincter, pelvic floor, anal canal, and rectum. There is often associated injury to the urethra, the bony pelvis, and the soft tissues of the buttocks.

Neurologic injury may involve upper motor neurons, which usually results in severe constipation, fecaloma, and soiling, or lower motor neurons, in which the anorectum is completely patulous and there is buttock anesthesia. More localized neurologic injury may involve the pudendal nerve in patients who strain or in whom there has been a prolonged second stage of labor. Diffuse neurologic abnormality may occur in demyelinating disease and in the neurologic degenerative process seen in the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome.

Sepsis around the anal canal may result in skeletal muscle destruction and fibrosis. This cause of incontinence may occur when inefficient or delayed drainage of anorectal sepsis has occurred and in patients with severe localized inflammatory disease of the anal canal, as may occur in Crohn’s disease or in deep penetrating ulcers associated with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome.

Congenital causes of incontinence may be anorectal agenesis, Hirschsprung disease, rectal reduplication, and anorectal dermoids, or the congenital abnormality may affect the neural tube, as in patients with meningomyelocele or its variants.

Diagnosis

Clinical Examination

Clinical examination identifies the principal cause of incontinence in most patients, but in certain instances specialized anorectal physiology is required for diagnosis and as a means of recommending whether surgical treatment is indicated.

Inspection of the perineum can identify scars from previous anal surgery, episiotomy, or obstetric injury. Often, a defect in the sphincter ring is apparent. The site of the anus should be noted. Anterior displacement suggests an ectopic anus (minor variant of anorectal agenesis). The presence of skin tags, fistulae, or the presence of patulous anus should be recorded. Inspection should then include examination during straining to exclude a rectal prolapse and to assess the degree of perineal descent and vaginal descent, cystocele, and rectocele.

Rectal examination should attempt to assess resting tone and the contractile activity of the external anal sphincter and the puborectalis. Rectal examination should also identify any defect in the sphincter and any gutter deformity, in addition to any palpable pathologic abnormality in the rectum.

Proctosigmoidoscopy should be performed to exclude proctitis, polyps, or any other colorectal pathology.

Specialized Diagnostic Techniques

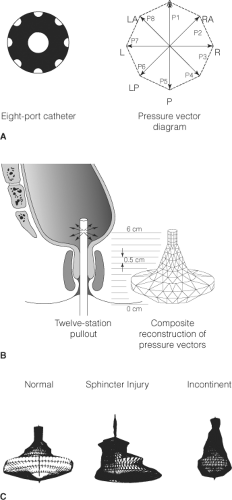

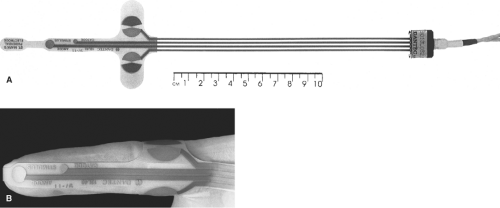

Anal manometry provides data on the maximum resting anal canal pressure and the maximum pressure generated during a maximum squeeze effort (Fig. 1). Manometry also helps to identify the length of the high-pressure zone, and vector manometry may be used to clarify areas of reduced anal pressure, signifying localized defects. In some circumstances, ambulatory manometry may be necessary. An inflatable balloon should then be inserted into the rectum and anal manometry performed during balloon distention to determine the presence or absence of the rectoanal inhibitory reflex. This reflex may be absent in Hirschsprung disease and in some patients with incontinence. Distention of a rectal balloon is a simple method of crudely assessing rectal capacity and rectal sensation. However, for compliance measurements of the rectum, integrated changes in intrarectal pressure are recorded with incremental volumes in the rectal balloon. Anal sensation should be measured using the technique of anal mucosal electrosensitivity in the lower, mid, and upper anal canal.

Electromyography was formerly used for mapping the external anal sphincter in patients with sphincter defects and in assessing ectopic anus. However, the use of needle electrodes is painful and poorly tolerated

by patients, particularly if there is scar tissue. Likewise, measurement of fiber density as an assessment of the degree of denervation may be performed by repeated sampling of the external sphincter and puborectalis by use of concentric needle electrodes. For the same reason, patients find this investigation difficult to tolerate and are not particularly compliant. By contrast, conduction studies are less invasive and give an assessment of pudendal neuropathy. Pudendal nerve terminal motor latency measurements can be made by stimulating the pudendal nerve as it winds around the ischial tuberosity and recording the evoked contraction in the external sphincter after stimulation (Fig. 2). Conduction delays are associated with pudendal neuropathy, but there is considerable observer variation with this measurement.

by patients, particularly if there is scar tissue. Likewise, measurement of fiber density as an assessment of the degree of denervation may be performed by repeated sampling of the external sphincter and puborectalis by use of concentric needle electrodes. For the same reason, patients find this investigation difficult to tolerate and are not particularly compliant. By contrast, conduction studies are less invasive and give an assessment of pudendal neuropathy. Pudendal nerve terminal motor latency measurements can be made by stimulating the pudendal nerve as it winds around the ischial tuberosity and recording the evoked contraction in the external sphincter after stimulation (Fig. 2). Conduction delays are associated with pudendal neuropathy, but there is considerable observer variation with this measurement.

Fig. 2. The disposable pudendal electrode. (From Keighley MRB, Williams NS. Surgery of the Anus, Rectum, and Colon, 3rd ed. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders; 2008, with permission.) |

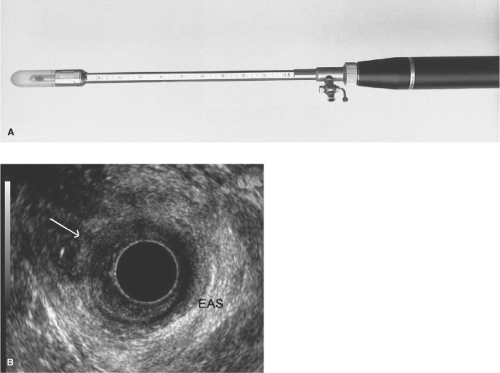

Ultrasound examination of the anal canal and rectum has superseded electromyography in the identification of sphincter defects. It is important to assess the length of any injury in the anal canal as well as its circumferential extent and position. Anal ultrasonography can be used for dynamic assessment of contractility, as well as definition of anatomic defects (Fig. 3A and B), morphology, and pathologic conditions (e.g., abscess and fistula). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the anorectum may provide additional important information, particularly in injuries and disorders affecting the pelvis floor.

Fig. 3. A and B: Anal ultrasound. (From Keighley MRB, Williams NS. Surgery of the Anus, Rectum, and Colon, 3rd ed. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders; 2008, with permission.) |

Many patients with fecal incontinence have some impairment of rectal evacuation. Thus, assessment of rectal emptying by isotopic techniques or during videoproctography is indicated for some patients. Videoproctography may also be needed to exclude coexisting abnormalities, such as intussusception, perineal descent, and rectocele, as well as to provide playback images to record pelvic floor movements during contraction and attempted defecation.

In general, patients with low resting anal pressures, a short high-pressure zone, gross perineal descent, anal anesthesia, gross prolongation of pudendal nerve terminal motor latency and those with poor external sphincter contractility do badly after attempted reconstructive surgery. Thus, for such patients, counseling that there are alternative therapies other than conventional surgical reconstructions that are more likely to improve a patient’s quality of life is needed.

Treatment

Conservative Therapy

Many patients with fecal incontinence have a history of diarrhea. Under these circumstances, particularly if the incontinence is relatively mild, control of the diarrhea may achieve sufficient improvement and further therapy becomes unnecessary. Use of codeine phosphate and loperamide can be important. In patients with rapid transit times, tablets or capsules may not be absorbed, but an elixir may be.

Diet and Anal Hygiene Methods

Many patients with bowel incontinence find that bowel control is poor on a vegetarian diet. Foods that produce gas, for example, onions, root vegetables, beans, and brassicas, should be avoided if the sufferer has flatus incontinence. Alcohol is generally poorly tolerated in incontinence patients. Diets rich in animal protein and starch often suit patients who suffer with bowel incontinence. Many patients find that the timing of meals is critical for work and social events.

For those whose principal problem is soiling, washing with water, the use of wipes to remove fecal debris when visiting the toilet to micturate avoids perianal excoriation and soreness from fecal staining.

Physiotherapy and Biofeedback

Unquestionably, some patients can no longer contract the sphincter and pelvic floor complex appropriately in response to rectal distention. Others seem incapable of sphincter and pelvic floor contraction on command and tend to strain during attempted voluntary contraction. Another group finds it difficult to contract the sphincter and pelvic floor after recent injury because of pain and psychological trauma. Such patients may be improved dramatically by a series of pelvic floor exercises, faradism, electrical stimulation of the sphincter muscles, and biofeedback retraining. Biofeedback involves an afferent stimulus as a learning process to trigger pelvic floor and sphincter contraction. Biofeedback retraining may produce dramatic improvement in patients who have problems in learning the technique. Biofeedback may also heighten rectal sensory awareness. However, biofeedback is dependent on cooperation by the patient and personality synthesis between the therapist and the patient. For motivated patients, this form of treatment is useful in minor forms of incontinence. It may also be helpful as a preoperative conditioning process so that the discipline can be reinforced postoperatively.

Keeping the Rectum Empty

Recognition that surgical treatments for bowel incontinence rarely fully control the symptoms of flatus incontinence, soiling, and may result in deterioration of rectal emptying, conservative measures to keep the rectum empty have assumed a much greater role for therapy during the last decade.

The simplest approach is the use of glycerin or bisacodyl suppositories, but these only empty the rectum. Small volume enemas achieve greater compliance than phosphate enema but are less effective in emptying the left colon. Enemas are used by many with a neuropathic anorectum so as to achieve regular evacuation while preventing fecal impaction.

Self-administered rectal washout is the logical extension of colostomy irrigation. It was pioneered in countries where availability and cost of stoma appliances were prohibitively expensive. The technique has now been accepted in colorectal units. Management of incontinence by washouts has become an extension of the role of the stoma therapists or colorectal nurse specialists. It is curious that this simple measure has taken so long to become accepted as an alternative to a stoma and as an effective method of achieving predictable anal hygiene. Like colostomy irrigation, it requires a motivated patient who is psychologically able to accept the technique as an extension to normal toileting. There are now commercially available kits and nursing staff trained to teach and supervise rectal irrigation.

The principal is to teach patients to infuse a variable volume of fluid through a delivery system with an appropriate anal applicator so as to stimulate a series of mass left side colonic evacuations. As a consequence, the left colon is emptied of gas, liquid, and solid contents. If successful, patients may then feel clean for the rest of the day without the fear of urgency, soiling, or even flatus incontinence. The technique takes between 20 and 40 minutes at the beginning of the day and achieves almost complete continence for the rest of the day in over 80% of patients. Thus, in compliant poor outcome potential surgical patients, this procedure replaces the need for an operation with uncertain results and greatly improves patient’s quality of life. Consequently, individuals who master self-administered rectal washouts are largely able to lead independent social lives, allowing a full range of physical exercise and return to the workplace.

Postanal Repair and Anterior Levatorplasty

The aim of postanal repair is to restore the anorectal angle; this used to be considered essential for continence. The operation is now rarely performed as the long-term results are poor.

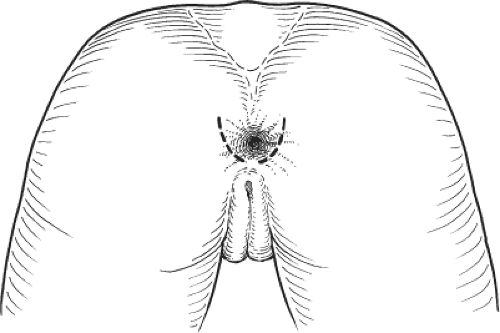

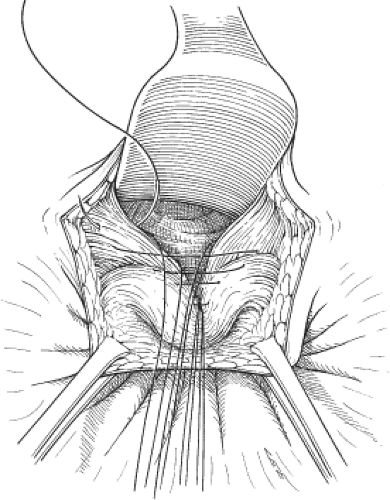

Anterior levatorplasty is useful in patients with rectocele and in many patients requiring sphincter repair, in whom, there is also a deficiency of the perineal body and the anterior aspect of the pelvic floor. The patient is placed in the prone jackknife or lithotomy position. Liberal infiltration of the rectovaginal septum with a weak adrenaline solution and a local anesthetic is often advisable. A transverse incision is made across the perineum, between the rectum and the vagina, but in front of the anterior border of the anal sphincters. The external anal sphincter is identified posteriorly, and the entire rectovaginal septum is dissected free to the level of the pelvic peritoneum, where the rectum and the vagina move away from one another at the rectovaginal cul-de-sac. The posterior vaginal wall is then dissected from the levator muscles, so that the anterior limbs of the puborectalis can be easily identified. Repair involves approximating the anterior aspect of the puborectalis in the midline between the rectum and the vagina. In patients with an obstetric sphincter injury, the anterior aspect of the external anal sphincter is also plicated or repaired (Fig. 4).

Total pelvic floor repair is a combination of postanal repair with anterior levatorplasty. It is now rarely used as the long-term results are poor.

Sphincter Repair

Sphincter repair is indicated for patients with a localized defect in the external anal sphincter, provided the healthy sphincter is capable of vigorous contraction. The operation may be needed for postobstetric injury, division of the sphincter after fistula surgery, or traumatic injuries of the perineum. In each of these three situations, the specific method of repair may have to be modified according to the extent of damage.

Fig. 4. Anterior levatorplasty. (From Keighley MRB, Williams NS. Surgery of the Anus, Rectum, and Colon, 3rd ed. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders; 2008, with permission.) |

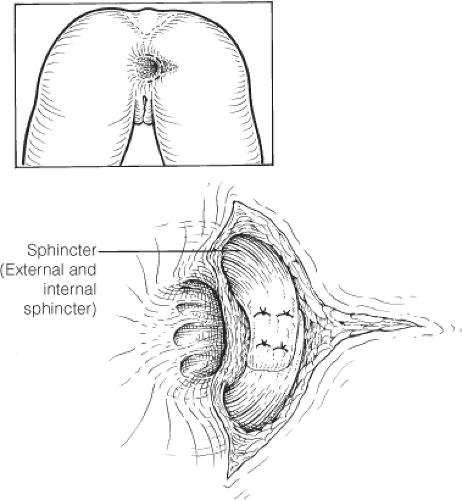

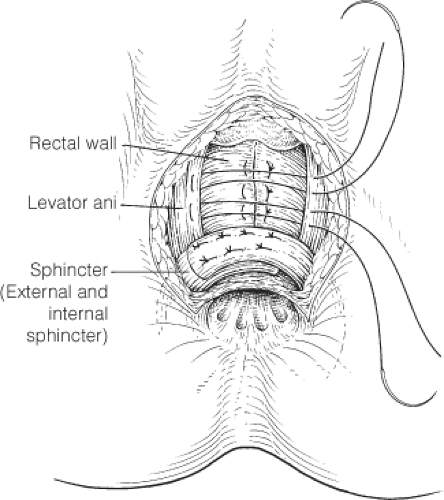

The patient may be operated on in the prone jackknife or lithotomy position. Prior infiltration with a weak adrenaline solution and a local anesthetic is always advisable. In postobstetric sphincter injuries, a cruciate incision may be used to provide excellent access to the rectovaginal septum, the perineal body, and the sphincters. The cruciate incision is usually closed as a Z-plasty, but there is a tendency for wounds to break down. Thus, a circumanal incision is preferred by most surgeons, leaving the center open for drainage (Fig. 5). For a defect after previous fistulotomy, a circumanal incision is usually more appropriate (Fig. 6). In traumatic perineal injuries, the incision depends on the precise site of the defect. The first task is to dissect the external anal sphincter on either side of the defect and preserve, where possible, the internal anal sphincter. Stay sutures are placed on either side of the sphincter defect, and the scar tissue is divided. In patients with postobstetric injuries, the entire rectovaginal septum is dissected free so that an anterior levatorplasty (Fig. 7) can be combined with sphincter repair. However, in the case of traumatic injury and defects after fistula operations, levatorplasty is rarely necessary unless one is dealing with an anterior deficiency. In patients with perineal trauma, it may be necessary to identify any defect that may be present in the anorectum as well as by MRI. In such cases, reconstitution of the anorectum by repair of its circular smooth-muscle fibers and mucosa may have to be combined with sphincter repair.

Sphincter repair itself involves a flap-over technique that takes one half of the divided sphincter muscle under the other, which thereby tightens the sphincter and eliminates the defect. It is wise to use a closed suction drain if there has been any difficulty with hemostasis. If the patient has a large sphincter defect or a history of impaired rectal evacuation, or is at risk of sepsis, it would be wise to consider a temporary covering loop colostomy.

Postoperative complications include sepsis, hematoma, stenosis with impairment of rectal emptying, and breakdown of the repair, which can lead to a suprasphincteric fistula. Thus, it is essential that all patients are carefully counseled. It is also important to use perioperative antibiotic cover, mild laxatives, and ensure careful attention to local dressings and hygiene. Fecal impaction must be avoided. The short-term success rate of sphincter repair is ∼75%,

but there is deterioration in the quality of continence with time. All the long-term evidences indicate that <50% of patients having a delayed sphincter repair are fully continent at 5 years.

but there is deterioration in the quality of continence with time. All the long-term evidences indicate that <50% of patients having a delayed sphincter repair are fully continent at 5 years.

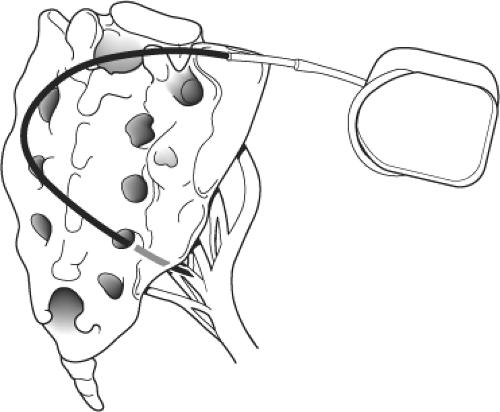

Sacral Nerve Stimulation

This new treatment is still being evaluated, since results exceeding 5 to 7 years are not yet available. Nevertheless, the results reported thus far indicate that this treatment must now be considered carefully in the therapeutic options available for management of bowel incontinence.

It is unclear how sacral nerve stimulation (SNS) achieves continence. It may also improve impaired rectal evacuation and has been applied for treatment of intractable constipation. It appears therefore to coordinate rectal evacuation and sphincteric contraction. Treatment was first explored in patients with an intact sphincter and pelvic floor who had features of pudendal neuropathy. Since then, it has been assessed in patients with a sphincter deficiency and poorly contracting muscle. Soon the results of sphincter repair will be compared with SNS. However, given the potential risks of sphincter repair, particularly sepsis and breakdown, SNS if equivalent, may have an important role in the future with patients with an anatomical defect in the sphincter ring.

A careful selection process is essential. Candidates for SNS must be psychologically stable and sufficiently intelligent to cope with programming the implanted stimulator. Patients are only offered treatment if temporary percutaneous SNS has been effective over 4 to 6 weeks. Usually, S4 on one side of the sacral foramena is stimulated. The implantable device is placed in a subcutaneous pocket; either the perineum or in the supra pubic region and connected to the stimulator electrodes, which is programmed according to clinical efficacy and manometry (Fig. 8). The implantable device is expensive. There may be battery failure, migration of leads, and problems with electrical connections requiring reoperation and careful surveillance.

So far, the 5-year results indicate that in carefully selected patients, quality of life and quality of continence are greatly improved in 60% to 80%; however, continence to gas and avoidance of soiling are frequently imperfect.

Fig. 8. Sacral nerve stimulation (SNS). (From Keighley MRB, Williams NS. Surgery of the Anus, Rectum, and Colon, 3rd ed. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders; 2008, with permission.) |

Nerve stimulation is usually switched off at night, which prolongs battery life. The stimulator is often used during physical exercise, which is normally associated with a greater risk of leakage.

Clearly, SNS has the potential for considerable therapeutic benefit and the long-term results will be carefully assessed before it is used widely. Recent experience may advise the immediate use of the implantable device rather than a trial of temporary pacing.

Rerouting of Ectopic Anus

The patient is catheterized and placed in the prone jackknife or the lithotomy position. Previous infiltration with a weak adrenaline solution in a local anesthetic is advised around the ectopic anus. The external anal sphincter should have been identified preoperatively by electromyography or MRI. A disk of skin is taken from the center of the defined external anal sphincter, and a plane of dissection is developed through the center of the sphincter ring. A gauze swab is placed in the future site of the anal canal.

The ectopic anus is then dissected from the back of the vagina or from the back of the prostate by use of a circumanal incision. The anus must be mobilized for at least 6 or 7 cm from the perineum above the levators before it is rerouted to its correct anatomic site. Stay sutures are placed on the lateral margins of the anus after it has been thoroughly mobilized, particularly anteriorly. The stay sutures are used to draw the anorectum through the center of the external anal

sphincters to its correct anatomic position (Fig. 9). The mucosa is then sutured to the edges of the skin disk, and an anterior levatorplasty is performed to reconstitute the perineal body. The biggest hazard of rerouting the anal canal is fecal impaction. Many patients have chronic constipation and some impairment of evacuation. Thus, a regimen of postoperative laxatives is essential to achieve a satisfactory long-term outcome.

sphincters to its correct anatomic position (Fig. 9). The mucosa is then sutured to the edges of the skin disk, and an anterior levatorplasty is performed to reconstitute the perineal body. The biggest hazard of rerouting the anal canal is fecal impaction. Many patients have chronic constipation and some impairment of evacuation. Thus, a regimen of postoperative laxatives is essential to achieve a satisfactory long-term outcome.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree