CHAPTER 5 Functional anatomy of the musculoskeletal system

The skeletal system consists of the specialized supporting connective tissues of the bony skeleton and the associated tissues of joints, including cartilage. Cartilage is the fetal precursor tissue in the development of many bones; it also supports non-skeletal structures, as in the ear, larynx and tracheobronchial tree. Bone provides a rigid framework which protects and supports most of the soft tissues of the body and acts as a system of struts and levers which, through the action of attached skeletal muscles, permits movement of the body. Bones of the skeleton are connected with each other at joints which, according to their structure, allow varying degrees of movement. Some joints are stabilized by fibrous tissue connections between the articulating surfaces, while others are stabilized by tough but flexible ligaments. Skeletal muscles are attached to bone by strong flexible, but inextensible, tendons which insert into bone tissue. The entire assembly forms the musculoskeletal system; all its cells are related members of the connective tissue family and are derived from mesenchymal stem cells.

CARTILAGE

MICROSTRUCTURE OF CARTILAGE

Extracellular matrix

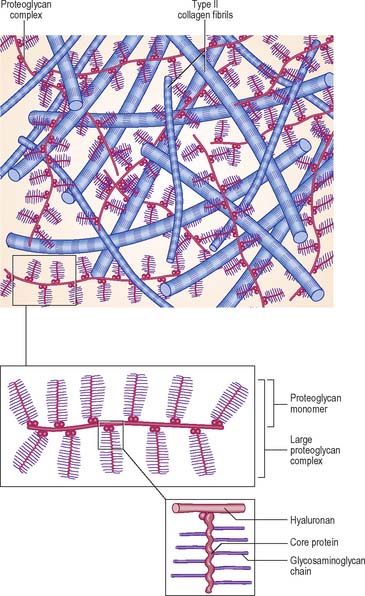

The extracellular matrix is composed of collagen and, in some cases, elastic fibres, embedded in a highly hydrated but stiff ground substance (Fig. 5.1). The components are unique to cartilage, and endow it with unusual mechanical properties. The ground substance is a firm gel, rich in carbohydrates and predominantly acidic. The chemistry of the ground substance is complex. It consists mainly of water and dissolved salts, held in a meshwork of long interwoven proteoglycan molecules together with various other minor constituents, mainly proteins or glycoproteins.

Synthesis of matrix

Chondrocytes synthesize and secrete all of the major components of the matrix. Collagen is synthesized within the rough endoplasmic reticulum in the same way as in fibroblasts, except that type II rather than type I procollagen chains are made. These assemble into triple helices and some carbohydrate is added at this stage. After transport to the Golgi apparatus, where further glycosylation occurs, they are secreted as procollagen molecules into the extracellular space. Here, terminal registration peptides are cleaved from their ends, so forming tropocollagen molecules, and final assembly into collagen fibres takes place. Core proteins of the proteoglycan complexes are also synthesized in the rough endoplasmic reticulum and addition of GAG chains begins. The process is completed in the Golgi complex. Hyaluronan, which lacks a protein core, is synthesized by enzymes on the surface of the chondrocyte; it is not modified post-synthetically, and is extruded directly into the matrix without passing through the endoplasmic reticulum.

Hyaline cartilage

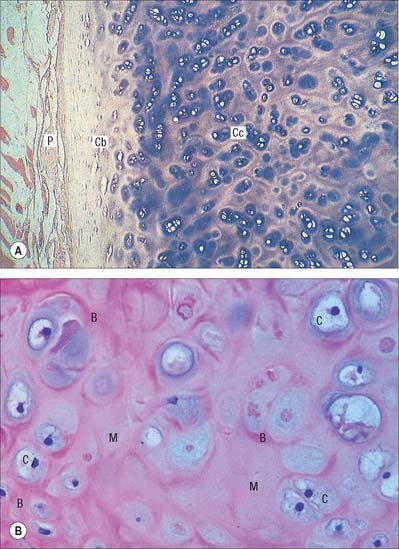

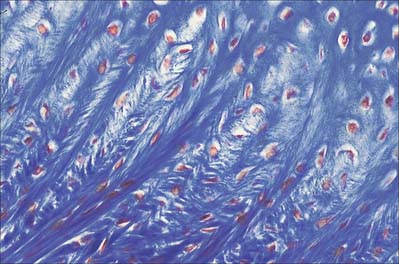

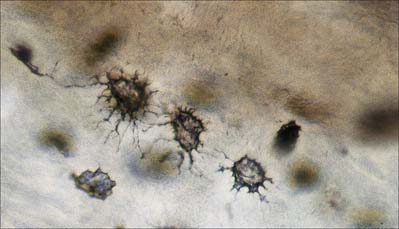

Hyaline cartilage has a homogeneous glassy, bluish opalescent appearance. It has a firm consistency and some elasticity. Costal, nasal, some laryngeal, tracheobronchial, all temporary (developmental) and most articular, cartilages are hyaline. The arytenoid cartilage changes from hyaline at its base, to elastic cartilage at its apex. Size, shape and arrangement of cells, fibres and proteoglycan composition vary at different sites and with age. The chondrocytes are flat near the perichondrium and rounded or angular, deeper in the tissue. They are often grouped in pairs, sometimes more, forming cell nests (isogenous cell groups) which are daughter cells of a common parent chondroblast: apposing cells have a straight outline. The matrix is typically basophilic (Fig. 5.2) and metachromatic, particularly in the lacunar capsule, where recently formed, territorial matrix borders the lacuna of a chondrocyte. The paler-staining interterritorial matrix between cell nests is older synthetically. Fine collagen fibres are arranged in a basket-like network (Fig. 5.3), but are often absent from a narrow zone immediately surrounding the lacuna. An isogenous cell group, together with the enclosing pericellular matrix, is sometimes referred to as a chondron.

Articular hyaline cartilage

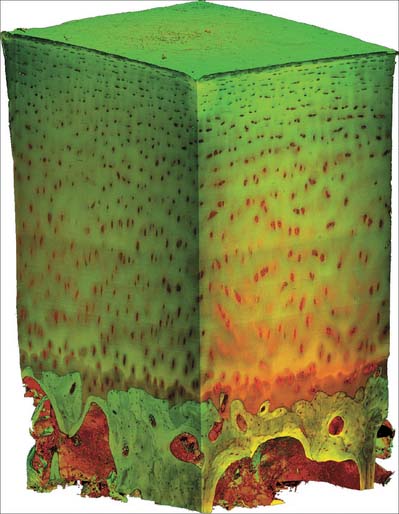

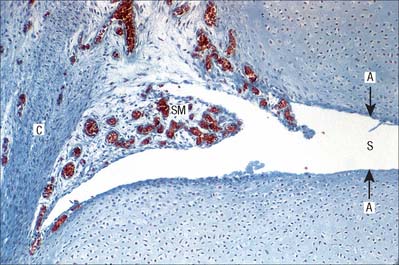

Articular hyaline cartilage covers articular surfaces in synovial joints (Fig. 5.4). It provides an extremely smooth, resistant surface bathed by synovial fluid, which allows almost frictionless movement. Its elasticity, together with that of other articular structures, dissipates stresses, and gives the whole articulation some flexibility, particularly near extremes of movement. Articular cartilage is particularly effective as a shock-absorber, and resists the large compressive forces generated by weight transmission, especially during movement.

Articular cartilage does not ossify. It varies from 1 to 7 mm in thickness and is moulded to the shape of the underlying bone, indeed it often accentuates and modifies the surface geometry of the bone. It is thickest centrally on convex osseous surfaces, and the reverse is true of concave surfaces. Its thickness decreases from maturity to old age. The surface of articular cartilage lacks a perichondrium; synovial membrane overlaps and then merges into its structure circumferentially (see Fig. 5.32).

Adult articular cartilage shows a structural zonation with increasing depth from the surface. The arrangement of collagen fibres has been variously described as plexiform, helical, or in the form of serial arcades which radiate from the deepest zone to the surface, where they follow a short tangential course before returning radially. If the surface of an articular cartilage is pierced by a needle, a longitudinal split-line remains after withdrawal. For any given joint, the patterns of split-lines are constant and distinctive and follow the predominant directions of collagen bundles in tangential zones of cartilage. These patterns may reveal tension trajectories set up in surrounding cartilage during joint movement.

The sequence of structural features outlined above is also typical of cartilaginous growth plates (see p. 95). During radial epiphysial growth, the extension of endochondral ossification into overlying calcified cartilage starts with the development of isogenous groups followed by the appearance of hypertrophic cells arranged in vertical columns. This ceases in maturity, but the zones persist throughout life. The same terminal mechanism also occurs in bones which lack epiphyses.

Fibrocartilage

Fibrocartilage is dense, fasciculated, opaque white fibrous tissue. It contains fibroblasts and small interfascicular groups of chondrocytes. The cells are ovoid and surrounded by concentrically striated matrix (Fig. 5.5). When present in quantity, as in intervertebral discs, fibrocartilage has great tensile strength and appreciable elasticity. In lesser amounts, as in articular discs, the glenoid and acetabular labra, and the cartilaginous lining of bony grooves for tendons and some articular cartilages, it provides strength, elasticity and resistance to repeated pressure and friction. It is resistant to degenerative change.

The articular surfaces of bones which ossify in mesenchymal membranes (e.g. squamous temporal, mandible and clavicle) are covered by white fibrocartilage. The deep layers, adjacent to hypochondral bone, resemble calcified regions of the radial zone of hyaline articular cartilage. The superficial zone contains dense parallel bundles of thick collagen fibres, interspersed with typical dense connective tissue fibroblasts and little ground substance. Fibre bundles in adjacent layers alternate in direction, as they do in the cornea. A transitional zone of irregular bundles of coarse collagen and active fibroblasts separates the superficial and deep layers. The fibroblasts are probably involved in elaboration of proteoglycans and collagen, and may also constitute a germinal zone for deeper cartilage. Fibre diameters and types may differ at different sites according to the functional load.

Elastic cartilage

Elastic cartilage occurs in the external ear, corniculate cartilages, epiglottis and apices of the arytenoids. It contains typical chondrocytes, but its matrix is pervaded by yellow elastic fibres, except around lacunae (where it resembles typical hyaline matrix with fine type II collagen fibrils) (Fig. 5.6). Its elastic fibres are irregularly contoured and show no periodic banding. Most sites in which elastic cartilage occurs have vibrational functions, such as laryngeal sound wave production, or the collection and transmission of sound waves in the ear. Elastic cartilage is resistant to degeneration; it can regenerate to a limited degree following traumatic injury, e.g. the distorted repair of a ‘cauliflower ear’.

DEVELOPMENT AND GROWTH OF CARTILAGE

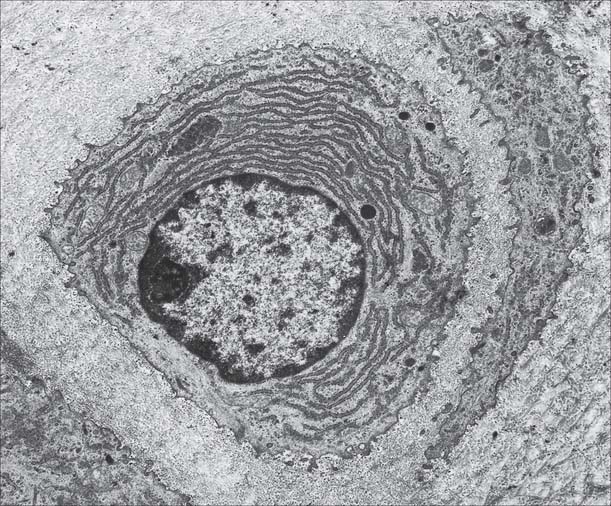

Cartilage is usually formed in embryonic mesenchyme. Mesenchymal cells proliferate and become tightly packed: the shape of their condensation foreshadows that of the future cartilage. They also become rounded, with prominent round or oval nuclei and a low cytoplasm: nucleus ratio. Adjacent cells are linked by gap junctions. Each cell next secretes a basophilic halo of matrix, composed of a delicate network of fine type II collagen filaments, type IX collagen and cartilage proteoglycan core protein, i.e. it differentiates into a chondroblast (Fig. 5.7). In some sites, continued secretion of matrix separates the cells, producing typical hyaline cartilage. Elsewhere, many cells become fibroblasts: collagen synthesis predominates and chondroblastic activity appears only in isolated groups or rows of cells which become surrounded by dense bundles of collagen fibres to form white fibrocartilage. In yet other sites, the matrix of early cellular cartilage is permeated first by anastomosing oxytalan fibres, and later by elastin fibres. In all cases, developing cartilage is surrounded by condensed mesenchyme which differentiates into a bilaminar perichondrium. The cells of the outer layer become fibroblasts and secrete a dense collagenous matrix lined externally by vascular mesenchyme. The cells of the inner layer contain differentiated, but mainly resting, chondroblasts or prechondroblasts.

BONE

MACROSCOPIC ANATOMY OF BONE

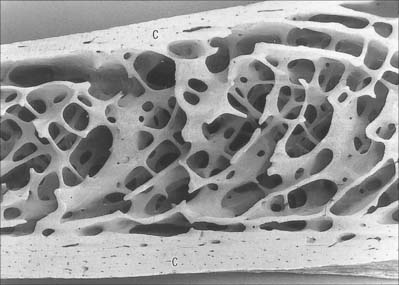

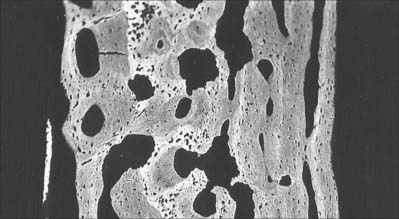

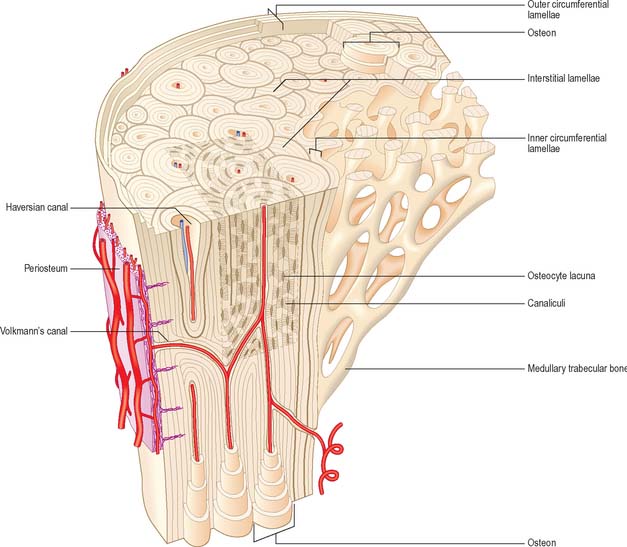

Macroscopically, living bone is white. Its texture is either dense like ivory (compact bone), or honeycombed by large cavities (trabecular, cancellous or spongy bone), where the bony element is reduced to a latticework of bars and plates (trabeculae) (Fig. 5.8, Fig. 5.9). Compact bone is usually limited to the cortices of mature bones (cortical bone) and is of great importance in providing their strength. Its thickness and architecture vary for different bones, according to their overall shape, position and functional roles. The cortex plus the hollow medullary canal of long bones allows combination of strength with low weight. Cancellous bone is usually internal, giving additional strength to cortices and supporting the bone marrow. Bone forms a reservoir of metabolic calcium (99% of body calcium is in the bony skeleton) and phosphate which is under hormonal and cytokine control.

Bones vary not only in their primary shape but also in lesser surface details, or secondary markings, which appear mainly in postnatal life. Most bones display features such as elevations and depressions (fossae), smooth areas and rough ridges. Numerous names are used to describe these secondary features. Some articular surfaces are called fossae (e.g. the glenoid fossa); lengthy depressions are grooves or sulci (e.g. the humeral bicipital sulcus); a notch is an incisura, and an actual gap is a hiatus. A large projection is termed a process or, if elongated and slender or pointed, a spine. A curved process is a hamulus or cornu (e.g. the pterygoid hamuli of the sphenoid bone and the cornua of the hyoid). A rounded projection is a tuberosity or tubercle, and occasionally a trochanter. Long elevations are crests, or lines, if they are less developed; crests are wider and present boundary edges or lips. An epicondyle is a projection close to a condyle and is usually a site where the common tendon of a superficial muscle group or the collateral ligament of the adjacent joint are attached. The terms protuberance, prominence, eminence and torus are less often applied to certain bony projections. The expanded proximal ends of many long bones are often termed the ‘head’ or caput (e.g. humerus, femur, radius). A hole in bone is a foramen, and becomes a canal when lengthy. Large holes may be called apertures or, if covered largely by connective tissue, fenestrae. Clefts in or between bones are fissures. A lamina is a thin plate; larger laminae may be called squamae (e.g. the temporal squama). Large areas on many bones are featureless and often smoother than articular surfaces, from which they differ because they are pierced by many visible vascular foramina. This texture occurs where muscle is directly attached to bone, and small blood vessels pass through the foramina from bone to muscle, and perhaps vice versa. Areas covered only by periosteum are similar, but vessels are less numerous.

MICROSTRUCTURE OF BONE

Bone matrix

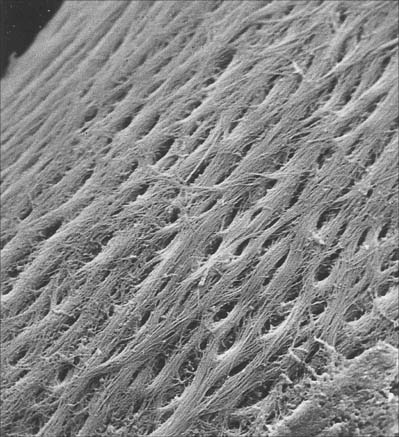

Bone matrix is the mineralized extracellular material of bone; like general connective tissues, it consists of a ground substance in which numerous collagen fibres are embedded, usually ordered in parallel branching arrays (Fig. 5.10). In mature bone, the matrix is moderately hydrated, and 10–20% of its mass is water. Of its dry weight, 60–70% is made up of inorganic, mineral salts (mainly microcrystalline calcium and phosphate hydroxides, hydroxyapatite (see below), approximately 30% is collagen and the remainder is non-collagenous protein and carbohydrate, mainly conjugated as glycoproteins. The proportions of these components vary with age, location and metabolic status.

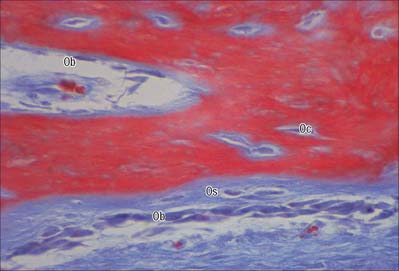

Osteoblasts

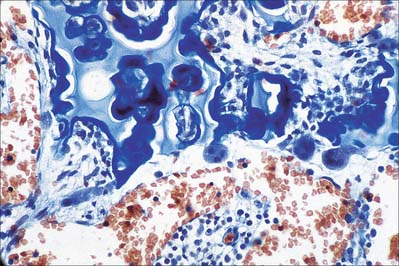

Osteoblasts are derived from osteoprogenitor (stem) cells of mesenchymal origin, which are present in the bone marrow and other connective tissues. They proliferate and differentiate, stimulated by bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs), into osteoblasts prior to bone formation. Osteoblasts are basophilic, roughly cuboidal mononuclear cells 15–30 μm across. Ultrastructurally, they have features typical of protein-secreting cells. They are found on the forming surfaces of growing or remodelling bone, where they constitute a covering layer (Fig. 5.11). In relatively quiescent adult bones they appear to be present mostly on endosteal rather than periosteal surfaces, but they also occur deep within compact bone where osteons are being remodelled. They are responsible for the synthesis, deposition and mineralization of the bone matrix, which they secrete. Once embedded in the matrix, they become osteocytes.

Osteoblasts play a key role in the hormonal regulation of bone resorption, since they express receptors for parathyroid hormone (PTH), 1,25-dihydroxy vitamin D3 and other promoters of bone resorption. During bone resorption, osteoblasts promote osteoclast differentiation via PTH-activated expression of cell surface RANKL, which binds to RANK on immature osteoclasts, establishes cell–cell contact and triggers contact-dependent osteoclast differentiation. In the presence of PTH, osteoblasts also downregulate secretion of osteoprotegerin, a soluble decoy ligand with higher affinity for RANKL. In conditions favouring bone deposition, secreted osteoprotegerin blocks RANKL binding to RANK and restricts numbers of mature osteoclasts. (For a recent review, see Blair et al 2007.)

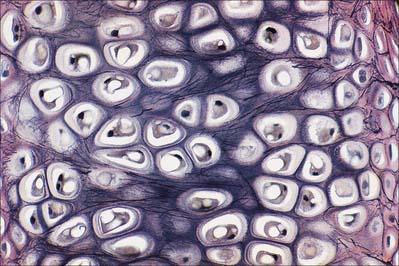

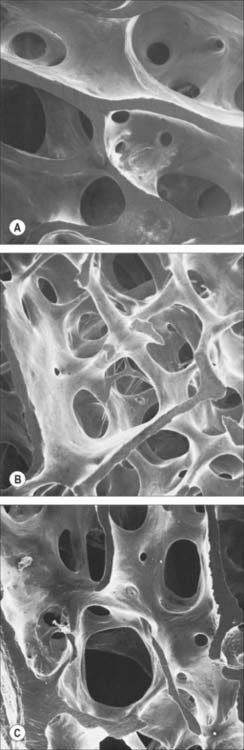

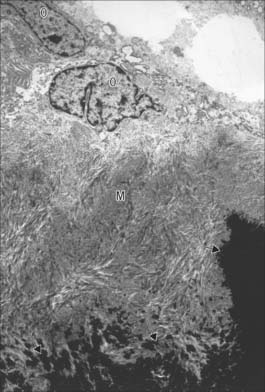

Osteocytes

Osteocytes constitute the major cell type of mature bone, and are scattered within its matrix, interconnected by numerous dendritic processes to form a complex cellular network (Fig. 5.12). They are derived from osteoblasts and are enclosed within their matrix but, unlike chondrocytes, they do not divide. Bone growth is appositional: new layers are added only to pre-existing surfaces and so, again unlike chondrocytes, osteocytes enclosed in lacunae do not secrete new matrix. The rigidity of mineralized bone matrix prevents internal expansion, which means that interstitial growth, which is characteristic of most tissues, does not occur in bone. Osteocytes retain contacts with each other and with cells at the surfaces of bone (osteoblasts and bone-lining cells) throughout their lifespan.

Mature, relatively inactive, osteocytes possess an ellipsoid cell body with the longest axis (25 μm) parallel to the surrounding bony lamella. The rather narrow rim of cytoplasm is faintly basophilic, contains relatively few organelles and surrounds an oval nucleus. Osteocytes in woven bone are larger and more irregular in shape (Fig. 5.13).

Osteoclasts

Functionally, osteoclasts are responsible for the local removal of bone during bone growth and subsequent remodelling of osteons and surface bone (see Fig. 5.25). They cause demineralization by proton release, which creates an acidic local environment, and organic matrix destruction by releasing lysosomal (cathepsin K) and non-lysosomal (e.g. collagenase) enzymes. Factors stimulating osteoclasts to resorb bone include osteoblast-derived signals; cytokines from other cells, e.g. macrophages and lymphocytes; blood-borne factors, e.g. parathyroid hormone and 1,25(OH)2 vitamin D3 (calcitriol). Calcitonin, produced by C cells of the thyroid follicle, reduces osteoclast activity.

Osteoclasts arise by fusion of monocytes derived from the bone marrow or other haemopoietic tissue. They probably share a common ancestor with macrophages within the granulocyte–macrophage lineage (see Fig. 4.12) but it is thought that they subsequently follow a distinct differentiation pathway.

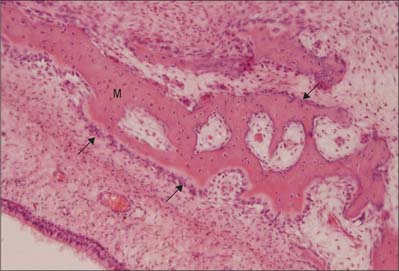

Osteons

In woven, or bundle, bone, the collagen fibres and bone crystals are irregularly arranged. The diameters of the fibres vary, so that fine and coarse fibres intermingle, producing the appearance of the warp and weft of a woven fabric. Woven bone is typical of young fetal bones, but is also seen in adults during excessively rapid bone remodelling and repair of fractures (Fig. 5.14). It is formed by highly active osteoblasts during development, and is stimulated in the adult by fracture, growth factors, or prostaglandin E2.

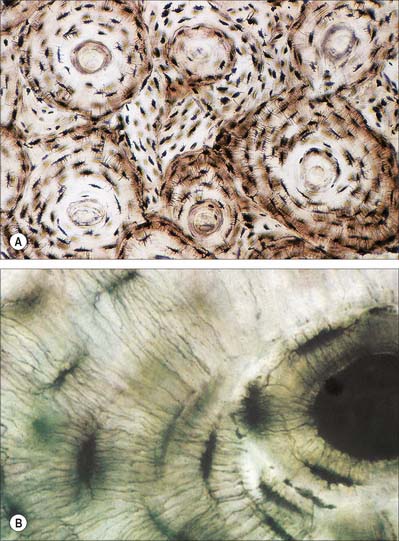

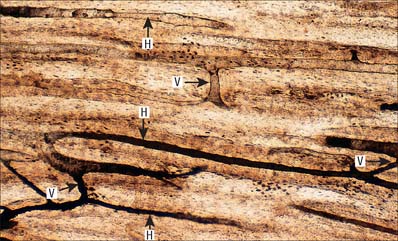

Lamellar bone makes up almost all of an adult osseous skeleton (Fig. 5.15, Fig. 5.16). The precise arrangement of lamellae varies from site to site, particularly between compact cortical bone and the trabecular bone within. In many bones a few lamellae form continuous circumferential layers at the outer (periosteal) and inner (endosteal) surfaces. However, by far the greatest proportion of lamellae are arranged in concentric cylinders around neurovascular channels called Haversian canals, to form the basic units of bone tissue which are the Haversian systems or osteons. Osteons usually lie parallel with each other (Fig. 5.17) and, in elongated bones such as those of the appendicular skeleton, with the long axis of the bone. They may also spiral, branch or intercommunicate, and some end blindly.

The central Haversian canals of osteons vary in size, with a mean diameter of 50 μm; those near the marrow cavity are somewhat larger. Each canal contains one or two capillaries lined by fenestrated endothelium and surrounded by a basal lamina which also encloses typical pericytes. They usually contain a few unmyelinated and occasional myelinated axons. The bony surfaces of osteonic canals are perforated by the openings of osteocyte canaliculi and are lined by collagen fibres.

Haversian canals communicate with each other and directly or indirectly with the marrow cavity via vascular (nutrient) channels called Volkmann’s canals, which run obliquely or at right angles to the long axes of the osteons (Fig. 5.17). The majority of these channels appear to branch and anastomose, but some join large vascular connections with vessels in the periosteum and the medullary cavity.

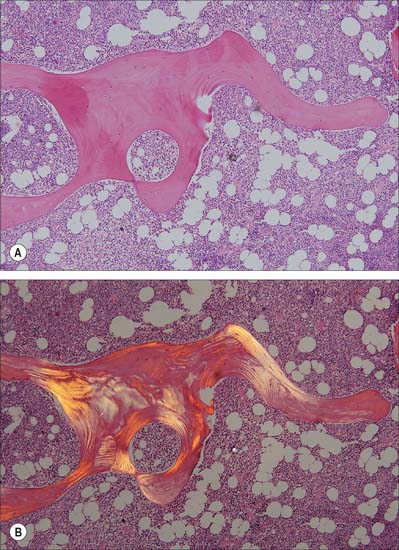

Trabecular bone

The organization of trabecular (cancellous, spongy) bone is basically lamellar, as shown most clearly under polarized light (Fig. 5.18). It takes the form of branching and anastomosing curved plates, tubes and bars of various widths and lengths which surround marrow cavities and are lined by endosteal tissue (Fig. 5.8, Fig. 5.9). Their thickness ranges from 50 to 400 μm. In general, bone lamellae are oriented parallel with the adjacent bone surface, and the arrangement of cells and matrix is similar to that found in circumferential and osteonic bone. Thick trabeculae and regions close to compact bone may contain small osteons, but blood vessels do not otherwise lie within the bony tissue, and osteocytes therefore rely on canalicular diffusion from adjacent medullary vessels. In young bone, calcified cartilage may occur in the cores of trabeculae, but this is generally replaced by bone during subsequent remodelling.

Remodelling

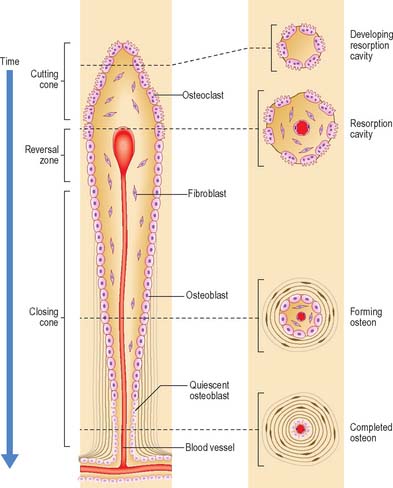

Remodelling of the interior of a bone depends upon the balance of resorption and deposition of bone, i.e. on the balanced activities of osteoclasts and osteoblasts. Osteoclasts first excavate a cylindrical tunnel by concerted action. A ‘cutting cone’ is formed by groups of osteoclasts moving at 50 μm/day, followed by osteoblasts which fill in the space so created. The osteoblasts deposit new osteoid matrix concentrically around a centrally ingrowing blood vessel, starting at the peripheral surface of the tunnel. This forms a ‘closing cone’ with 4000 osteoblasts/mm2. Deposition of successive, concentric lamellae follows, as cohorts of osteoblasts become embedded in the matrix they secrete, and are succeeded by new osteoblasts which line the free surface thus created, and secrete the next layer. In this way the walls of resorption cavities are lined with new lamellar matrix, and the vascular channels are progressively narrowed (Fig. 5.19). The pattern and extent of remodelling is dictated by the mechanical loads applied to the bone.

A hypermineralized basophilic cement line marks a site of reversal from resorption to deposition. Formation of osteons does not end with growth but continues variably throughout life. Remnants of circumferential lamellae of old osteons form interstitial lamellae between newer osteons (Fig. 5.15, Fig. 5.16A).

Periosteum, endosteum and bone marrow

The outer surface of bone is covered by a condensed, fibrocollagenous layer, the periosteum. The inner surface is lined by a thinner, more cellular, endosteum. Osteoprogenitor cells, osteoblasts, osteoclasts and other cells important in the turnover and homeostasis of bone tissue lie in these layers.

The periosteal layer is tethered to the underlying bone by extrinsic collagen fibres, Sharpey’s fibres, which penetrate deep into the outer cortical bone tissue. It is absent from articular surfaces, and from the points of insertion of tendons and ligaments (entheses) (see Fig. 5.46). The periosteum is highly active during fetal development, when it generates osteoblasts for the appositional growth of bone. These cells form a layer, two to three cells deep, between the fibrous periosteum and new woven bone matrix. Osteoprogenitor cells within the mature periosteum are indistinguishable morphologically from fibroblasts. Periosteum is important in the repair of fractures: where it is absent, e.g. within the joint capsule of the femoral neck, fractures are slow to heal.

NEUROVASCULAR SUPPLY OF BONE

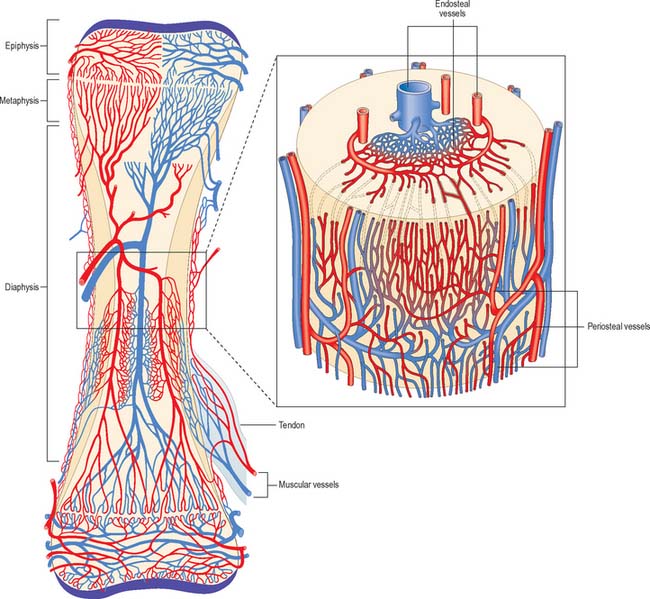

Vascular supply and lymphatic drainage

The osseous circulation supplies bone tissue, marrow, perichondrium, epiphysial cartilages in young bones, and, in part, articular cartilages. The vascular supply of a long bone depends on several points of inflow which feed complex and regionally variable sinusoidal networks within the bone. The sinusoids drain to venous channels which leave through all surfaces that are not covered by articular cartilage. The flow of blood through cortical bone in the shafts of long bones is mainly centrifugal (Fig. 5.20).

Medullary arteries in the shaft give off centripetal branches which feed a hexagonal mesh of medullary sinusoids that drain into a wide, thin-walled central venous sinus. They also possess cortical branches which pass through endosteal canals to feed fenestrated capillaries in osteons (Haversian systems). The central sinus drains into veins which retrace the paths of nutrient arteries, sometimes piercing the shaft elsewhere as independent emissary veins. Cortical capillaries follow the pattern of Haversian canals, and are mainly longitudinal with oblique connections via Volkmann’s canals (Fig. 5.17). At bone surfaces, cortical capillaries make capillary and venous connections with periosteal plexuses (Fig. 5.20). The latter are formed by arteries from neighbouring muscles which contribute vascular arcades with longitudinal links to the fibrous periosteum. From this external plexus a capillary network permeates the deeper, osteogenic periosteum. At muscular attachments, periosteal and muscular plexuses are confluent and the cortical capillaries then drain into interfascicular venules.

DEVELOPMENT AND GROWTH OF BONE

Intramembranous ossification

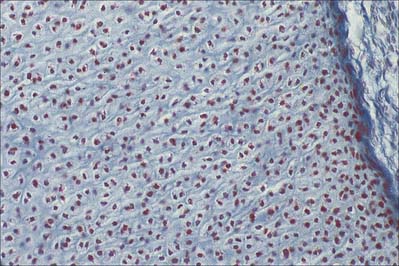

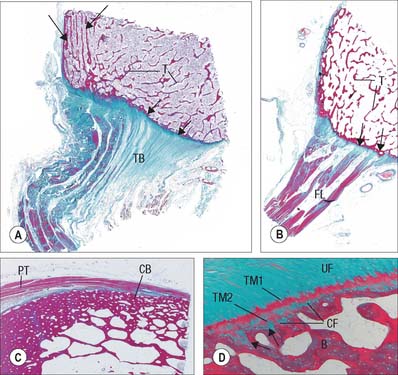

Intramembranous ossification is the direct formation of bone (membrane bone) within highly vascular sheets or ‘membranes’ of condensed primitive mesenchyme (Fig. 5.21). At centres of ossification, mesenchymal stem cells differentiate into osteoprogenitor cells which proliferate around the branches of a capillary network, forming incomplete layers of osteoblasts in contact with the primitive bone matrix. The cells are polarized because they secrete a fine mesh of collagen fibres and ground substance, osteoid, from the surface which faces away from the blood vessels. The earliest crystals appear in association with extracellular matrix vesicles produced by the osteoblasts; crystal formation subsequently extends into collagen fibrils in the surrounding matrix, producing an early labyrinth of woven bone, the primary spongiosa. As layers of calcifying matrix are added to these early trabeculae, the osteoblasts enclosed by matrix come to lie within primitive lacunae. New osteocytes retain intercellular contact by means of their fine cytoplasmic processes (dendrites) and, as these elongate, matrix condenses around them to form canaliculi.

As matrix secretion, calcification and enclosure of osteoblasts proceed, the trabeculae thicken and the intervening vascular spaces become narrower. Where bone remains trabecular, the process slows and the spaces between trabeculae become occupied by haemopoietic tissue. Where compact bone is forming, trabeculae continue to thicken and vascular spaces continue to narrow. Meanwhile the collagen fibres of the matrix, secreted on the walls of the narrowing spaces between trabeculae, become organized as parallel, longitudinal or spiral bundles, and the cells they enclose occupy concentric sequential rows. These irregular, interconnected masses of compact bone each have a central canal, and are called primary osteons (primary Haversian systems). They are later eroded, together with the intervening woven bone, and replaced by generations of mature (secondary) osteons.

Endochondral ossification

The first appearance of a centre of primary ossification (Fig. 5.22) occurs when chondroblasts deep in the centre of the primitive shaft enlarge greatly, and their cytoplasm becomes vacuolated and accumulates glycogen. Their intervening matrix is compressed into thin, often perforated, septa. The cells degenerate and may die, leaving enlarged and sometimes confluent lacunae (primary areolae) whose thin walls become calcified during the final stages (Fig. 5.23

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree