Fibromatosis

The first and largest group of lesions involving the proliferation of fibrous tissue are best grouped under the term

fibromatosis and include a wide range of clinical pathologic entities that predominantly involve the soft tissue and are nonmetastasizing but are of orthopaedic interest because of their anatomical location, occasional involvement of bone, and their tendency to invade locally and even recur after surgical excision. The group of fibromatoses may be multiple and familial and may even regress spontaneously, presenting a broad range of clinical variation. Because receptors for estrogen and/or progesterone may be present in fibrous lesions, increased growth rates during periods of high endogenous levels of sex steroid hormones are possible (

1). Broadly speaking, the fibromatoses can be classified into those involving adults and those in a younger childhood population (

2) (

Table 8.1). Many fibroblastic lesions on light microscopy have been determined to be of myofibroblastic origin.

Dupuytren-type Fibromatosis and Contracture

A fibromatosis occurring in the palmar region may typically lead to limitation of extension of the involved fingers and, ultimately, fixed flexion deformities, the result of localized, small, firm, nodular fibrous lesions within the palmar fascia. This type of fibromatosis has been called Dupuytren contracture, after the Baron Guillaume Dupuytren, who first published the results of open palmar fasciotomy in 1832 (

3). Dupuytren occurs most frequently in men in the fifth to seventh decade of life and, although extremely rare in Mediterranean and Semitic populations, may be seen in as much as 25 percent of the male Celtic population. Although the reputed autosomal dominant trait is not often obvious, Dupuytren does exhibit the tendency of fibromatosis to be linked to other proliferative fibrous situations, and a so-called Dupuytren diathesis has been described, which consists of fibromatosis in several locations including palmar, knuckle pads, plantar, and even penile or Peyronie disease. It is more common in epileptics older than 40 years, alcoholics, diabetics, and patients confined to bed rest. Sanderson et al. (

4) have found higher fasting serum levels of cholesterol and triglycerides in patients with Dupuytren.

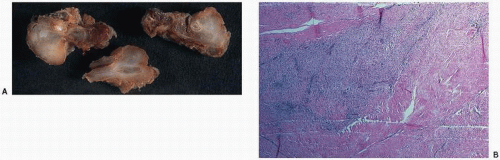

The gross pathology of Dupuytren is that of bands of abnormal clumping or cords of palmar or digital fascia in the otherwise normal-appearing glistening palmar fascia (

Fig. 8.1). Histologically, the unencapsulated and poorly demarcated nodules are distinguished from the surrounding normal tissue by an increased cellularity and lack of orderly arrangement. In fact, active lesions may be very cellular, with mitoses, and may be mistaken for a malignant tumor. Narrow blood vessels and hemosiderin deposition may occur, suggesting that microhemorrhage may be a factor in the progression of the lesion. Electron microscopic studies have supported the concept that the myofibroblast is the active proliferating cell. The myofibroblast is thought to be derived from the perivascular fibroblast and to contain contractile properties.

The natural course of fibromatosis is that of limited growth that may spontaneously regress. Thus, initial treatment is often observation. However, there is a role of surgery in controlling the proliferation and protecting hand function in severe cases or, in fact, in improving hand function, albeit not a definitive cure in all patients. The lack of invasion of involuntary muscle distinguishes Dupuytren-type fibromatosis from desmoids. Other entities that are similar in their histologic appearance to Dupuytren include plantar fibromatosis or Ledderhose disease, knuckle pad or dorsal fibromatosis, and Peyronie disease or penile fibromatosis.

Plantar Fibromatosis

Plantar fibromatosis is a palpable, slow growing, benign, nodular, circumscribed, but unencapsulated, fibromatosis involving the

plantar fascia of one or both feet (

5) (

Fig. 8.2). Although occurring throughout life, it is most commonly seen in patients younger than 30 years. It may be present at birth and associated with palmar fibromatosis. The tissue of origin is the medial aspect of the aponeurosis plantaris tibialis, commonly referred to as the plantar aponeurosis, a broad fibrous band connecting the inner calcaneal tubercle and the toes and inserting into the metatarsal bones. Branches support weight-bearing regions of the feet and anchor into the plantar skin (

5). Plantar fibromatosis is characterized by a high rate of local recurrence, and its proliferative and recurrent tendency can lead to extensive surgery over time, including amputation for control of the disease. Therefore, the initial surgical approach to plantar fibromatosis is critical. An argument can be made that not all plantar fibromatosis requires surgical intervention. Seemingly active growing lesions may naturally progress to a latent and indolent one (

5). Surgery may result in activation to more aggressive growth. Indications for surgery are pain and to relieve associated symptoms resulting from local extension and invasion. Incisions should be made away from the weight-bearing zones. Best results are achieved after initial treatment with wide radical excision (

5).

Desmoid Fibromatosis (Extra-abdominal Desmoid Tumor)

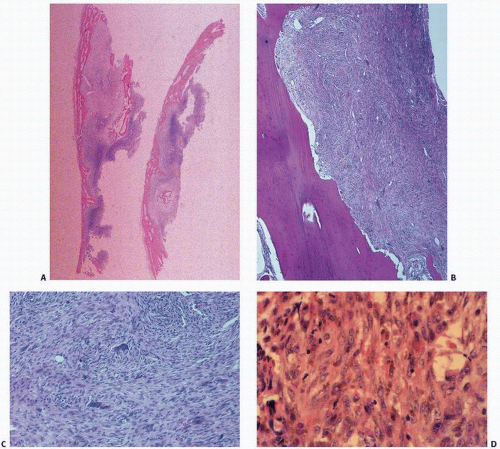

An additional adult-type fibromatosis is the so-called desmoid, which is distinct from fibromatosis in its characteristic tendency to invade skeletal muscle. The term “desmoid” derives from the Greek root meaning “band-like.” They have a rubbery tendinous consistency. This group of fibromatoses are deep-seated masses that may be multiple or familial and have a variable clinical course. Although there is usually a limited growth potential and they may regress spontaneously (desmoids may arise in scars), they have been noted in association with polyposis coli, colonic adenocarcinoma, epidermoid and sebaceous cysts, and osteomas in the so-called Gardner syndrome. Because they frequently occur locally after surgical excision and may invade muscle tendons and other tissue, they are potentially dangerous. Although a tumor may occur at any age and in either sex, the extra-abdominal desmoid tumor (eponyms include aggressive fibromatosis, musculoaponeurotic fibromatosis, and extra-abdominal desmoid tumor) has a peak incidence in women in the second and fourth decades. Clinically, desmoids present as firm diffuse swellings with ill-defined margins. Although pain is uncommon, local invasion of the bone may occur.

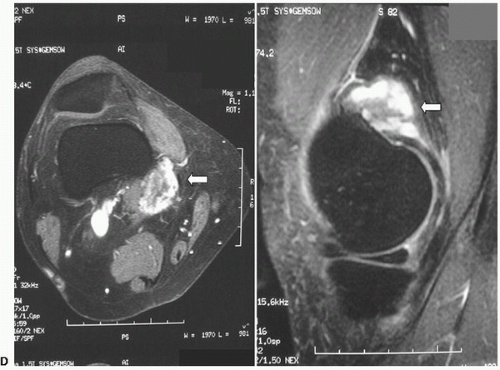

When adjacent to osseous structures, desmoid tumors can create a pressure effect and erode the cortex or cause a speculated periosteal reaction (

6).

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of desmoid tumors show a homogeneous or semi-homogeneous signal intensity that is isointense to skeletal muscle on T1-weighted images, and a heterogeneous high signal on T2-weighted images with collagenous bands

of low signal intensity by MR imaging often observed. After injection of intravenous gadolinium, moderate to marked enhancement may be seen.

Histologically, the lesion is characterized by an often very bland and almost imperceptible proliferation of spindle-shaped, thin fibroblasts; the proliferative lesion lacks pleomorphic cellularity and nuclear pleomorphism. Mitotic figures are very rare.

Desmoid tumors on needle core biopsies may be indistinguishable from scar tissue or reactive fibrosis. Many, but not all, of these tumors demonstrate nuclear β-catenin staining, which has been used to preclude the diagnosis of scar tissue or reactive fibrosis.

Calcification, and even metaplastic ossification, may be seen, particularly at the extreme periphery of the specimen and less commonly within the tissue.

This fibromatosis, which most typically has a predilection for the limbs and limb girdle, has been referred to as a musculoaponeurotic fibromatosis. Although the mainstay of treatment for this tumor has been surgical, local excision has been reported to result in local recurrences in up to 65 percent, suggesting radiotherapy as an adjuvant treatment in inoperable lesions.

However, there is no clear consensus on the optimal treatment of extra-abdominal desmoid tumors with current surgical treatments criticized because of morbidities and their marginal effect on outcome. A “wait and see” policy has its advocates and appears a rational alternative given the lack of controlled trial data and the known occurrence in some cases of spontaneous arrest (

7). Contemplating treatment of desmoid tumors is indeed a challenge to those who have taken the Hippocratic oath “Do no harm.”

With regard to the etiology of desmoid tumors, recent cytogenetic analyses of both abdominal and extra-abdominal tumors, including some with Gardner syndrome, have confirmed a clonal and probable neoplastic origin for the desmoid tumor (

8). Abnormalities and loss of chromosome 7 and changes in clonal interstitial deletions of the long arm of chromosome 5 (q21, q22) in association with polyposis suggest a “second hit” theory of inactivation of the adenomatous polyposis gene.

Occurrence of desmoids either before or after the diagnosis of Gardner syndrome (familial polyposis coli with multiple osteomas, epidermal and sebaceous cysts) is well established in the literature. The seriousness of the syndrome is in the development of bowel carcinoma, metastatic colonic adenocarcinoma, as well as bowel obstruction by intra-abdominal desmoids, ureteral obstruction by desmoids, and even spontaneous hemorrhage from desmoid tumors.

Avulsive Cortical Irregularity (Cortical Desmoid, Periosteal Desmoid)

Cystic or cortical bone abnormalities in the posterior medial aspect of the distal metaphyseal end of the femur have been described as cortical desmoids or “avulsion cortical irregularity” in the literature. However, these lesions show little in common with the desmoids previously described. They are benign, often silent clinically, and usually discovered incidentally following trauma (

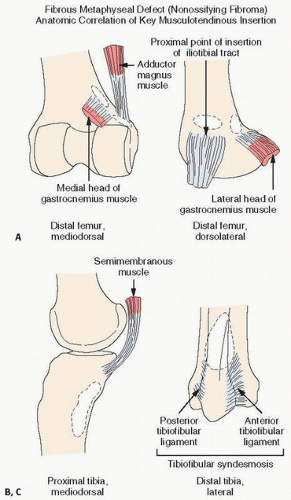

9).

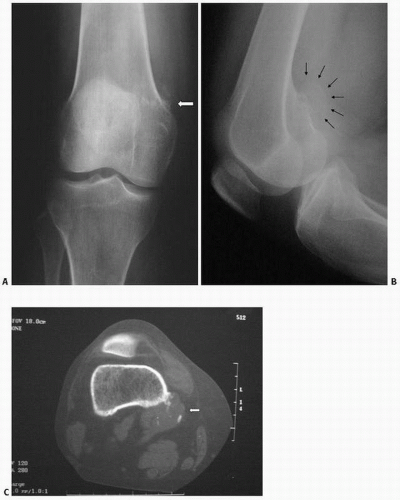

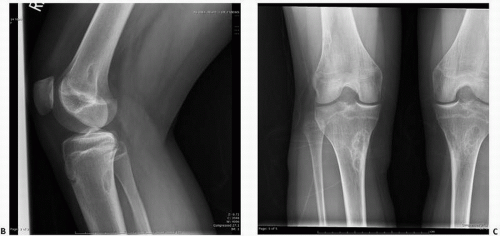

The lesion is observed almost exclusively on the posterior aspect of the medial condyle of femur, along the medial ridge of the linea aspera just above the adductor tubercle, which is the site of origin of the medial head of the gastrocnemius muscle and the transverse fibers of the adductor magnus (

Fig. 8.3).

On lateral plain radiographs, the lesion appears as an irregular shallow concave osteolytic lesion arising from the cortical bone surface and measuring less than 3 cm.

Margins are usually well defined, and the lesion occurs in the young teenager, in boys more than girls. They are most often encountered on the left side. MRI studies suggest that the lesion may be present bilaterally. It has a low signal on T1 and increased signal on T2.

Although the etiology is unknown, they have been felt to be the result of developmental error or secondary to trauma or avulsion at the site of insertion of the adductor magnus muscle tendon.

Histologically, tissue removed from these lesions, or anatomic variations, include benign inconspicuous fibrous tissue, and in some instances, some chondrocyte or cartilage proliferation. In

other instances, sparse inflammation or thickened fibrous periosteum, mineralized tissue and cartilage have suggested an osteochondroma-type lesion, although these myriad changes are also consistent with reactive or reparative tissue secondary to trauma (

10). Similar lesions have been documented in the humerus, tibia, fibula, radius, metatarsal, metacarpal, and distal phalanges, and on imaging, can suggest malignancy (

11).

Juvenile Fibromatoses

Numerous fibromatoses have been described in patients younger than 20 years, and only those of orthopaedic interest are reviewed (

Table 8.1). Infantile fibrosarcoma, or congenital fibrosarcoma-like fibromatosis, describes a tumor that most certainly does not metastasize but bears a similar, atypical cellular proliferation to those of the adult fibrosarcomatous lesions. Although local surgical excision is the treatment of choice, numerous treatment options have been proposed including excision, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy. Amputation should be avoided because of the natural history, which is that of a benign fibrous proliferation. Tumors have been described at birth or within the first 3 months of life and have been noted in the trunk, but most commonly on the extremities.

Infantile Myofibromatosis (Congenital Multiple Fibromatosis, Congenital Generalized Fibromatosis of Stout)

A lesion originally described by Stout in newborns and characterized by a rapidly fatal disease, with multiple fibrous nodules in subcutaneous tissues, skeletal muscle, bone, and visceral organs, termed “congenital generalized fibromatosis,” has now been recognized to be an initial neoplastic-like proliferation of myofibroblasts. However, this lesion subsequently is characterized by spontaneous resolution with a self-limited and indeed benign course (

12,

13). Although involvement of viscera by fibromatosis may carry with it a certain degree of mortality, the lesion, more often than not, takes a benign course. Two types have been described most recently: a soft tissue form involving subcutaneous tissue, with and without skeletal involvement, and a visceral type or disseminated form (

14). The soft tissue form carries a benign course with complete resolution, with a poor prognosis for the type involving the visceral organs. Both solitary and multicentric forms have been described. The solitary form, predominantly a disease of the first year of life but occurring at other ages, affects males more often than females. Most lesions involve the soft tissue or bone, most notably the head, neck, and trunk, with bone involvement predominantly in the cranium. Histologically, infantile myofibromatosis consists of fascicles of clumped spindle cells. There may be a rich network of vasculature. Some cells have more cigar-shaped nuclei, which is more typical of a smooth muscle cell. Whorled, collagenized backgrounds with pericytic patterns are often noted (

15). Hereditary factors are not yet clear, and the associated fibromas produced by large doses of estrogen have suggested humoral factors (

15).

Infantile myofibromatosis marks immunohistochemically with smooth muscle and muscle-specific actins and vimentin, but is S100, desmin, and CD34 negative. Although spontaneous remissions have been described, lesions with visceral metastases are usually treated with chemotherapy.

Juvenile Aponeurotic Fibroma

This distinct juvenile fibromatosis affects patients younger than 20 years and occurs mostly on the volar regions of the hands or feet (

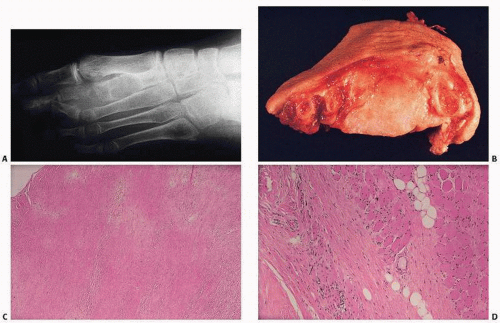

16). It is frequently calcified and may have a cartilaginous or chondroid component. Neither familial nor multicentric, it invades subcutaneous tissue, muscle, and nerves and tends to recur after surgical excision. Histologically, juvenile aponeurotic fibromatosis or fibroma is characterized by proliferating and often palisading fibroblasts infiltrating the surrounding fatty tissue (

Fig. 8.4). Fibroblasts merge with columns of cartilaginous or chondroid cells, often with hyalinized material that is focally calcified. There may be multinucleated giant cells.

Two phases have been described in the tumor’s growth: an initial phase characterized by diffuse tumor growth observed in infants and young children, and a late phase in an older age group with growth being more nodular and compact (

16).

The lack of malignant transformation and metastatic disease coupled with a tendency to recur after surgery has raised the issue of observation of a recurrent lesion if there is no functional impairment (

16).

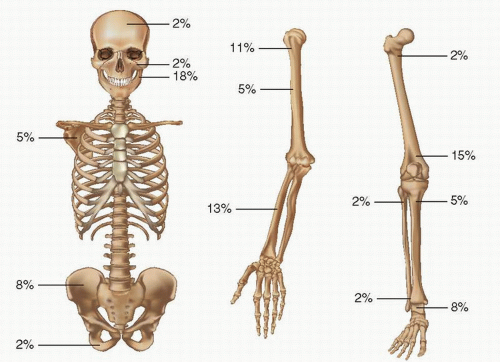

Fibrous Metaphyseal Defect (Nonossifying Fibroma)

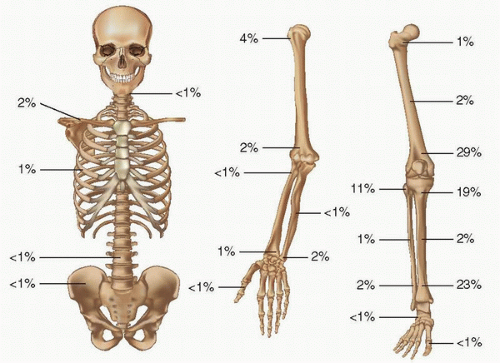

Fibrous metaphyseal defect (FMD) or nonossifying fibroma (NOF) and its smaller fibrous cortical defect counterparts have been considered the most common benign lesions of the skeletal system. Although the radiographic appearance of the classic NOF is pathognomonic, the proliferative spindle cell population, often in a matted, whorled, or storiform pattern with dispersed foam cells and benign multinucleated giant cells, mimics reactive and neoplastic conditions. There are now well-established clinical and anatomical facts associated with this lesion. In 1955, John Caffey (

17), in reviewing the prevalence, natural course, and diagnostic significance of this lesion, concluded that they were extremely common in a developing child. In fact, radiographs in more than 200 normal boys and girls revealed that 33 percent had one or more fibrous cortical defects. Generally appearing in the age range of 4 to 8 years, none were noted before the age of 2 years, and they were subsequently seen with decreasing frequency in later teenage years. The consistent anatomic locations of these lesions are the metaphyseal region of long bones of the lower extremities, especially the distal end of the femur. They occur particularly at anatomic sites corresponding to the insertion of a tendon or ligament into the perichondrium of the epiphyseal growth plate. With skeletal maturation, they move into the diaphysis, supporting original concepts that muscular pull or periosteal injury may be important factors in their development (

18) (

Figs. 8.5 and

8.6). Indeed, the long axis of the roentgenographically evident lesion often parallels the long axis of the bone. With maturation, defects persisting over long periods usually become sclerotic and appear away from the growing end of the bone, again suggesting developmental contribution. More than 50 percent of the lesions are multiple (

19,

20), and their roentgenographic appearances are characteristic. Lesions are usually eccentrically located in the bone. This cortical location is often associated with thinning of the cortex with inner boundaries demarcated by sclerosis. Often ovoid and multilocular in appearance, there is great variation in their size (

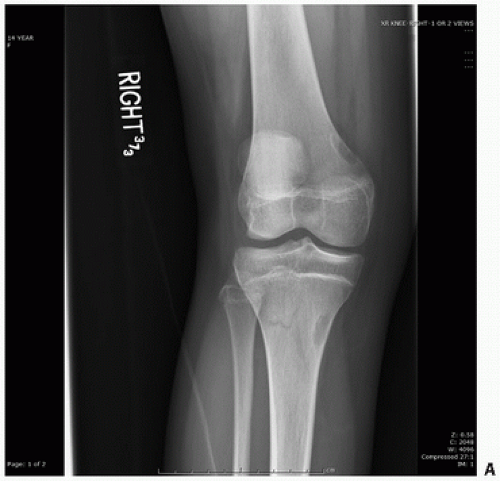

Fig. 8.7). As mentioned, most lesions are self-limited, with spontaneous regression in several years. Large lesions may lead to pathologic fracture, although surgical treatment should be minimal where appropriate.

Fracture is a definite risk once the NOF occupies more than 50 percent of the cross section of the bone. Both NOF and the fibrous cortical defects can become dense lesions as the patient matures.

Computed tomography (CT) scans demonstrate these lesions as well-defined lucencies, with density close to that of muscle. MRI scans show these lesions as areas of intermediate signal intensity in both T1-and T2-weighted images.

Multiple lesions may be associated with neurofibromatosis.

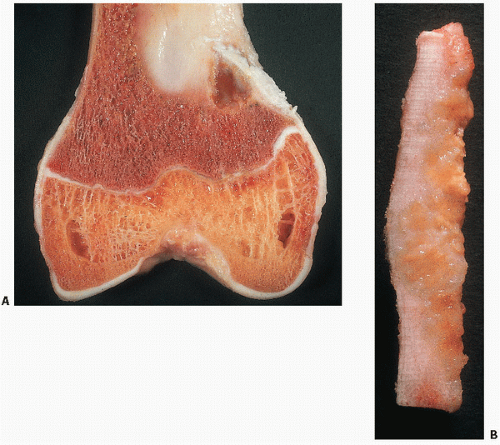

Grossly, FMDs are well circumscribed, and may be white, tan, or yellow depending on the amount of fibrous tissue, hemosiderin, and lipid accumulation, respectively (

Fig. 8.8).

Nonossifying fibromas consist of a proliferative population of spindle cells, usually in a swirling pattern, often admixed with other cells including foam cells or lipophages, and benign, multinucleated giant cells (

Fig. 8.9). Collagen production is rarely prominent. Hemosiderin is seen to a variable degree. In some instances, the proliferation of spindle cells may take on a cellular and even pleomorphic pattern, which could lead to misdiagnosis. Here, the classic roentgenographic appearance is extremely helpful to the pathologist in establishing the diagnosis. Because of their characteristic roentgenographic appearance, these lesions are commonly encountered and usually not biopsied.

A few cases of NOF with chromosome aberrations have been reported, all with near-diploid karyotypes and different structural rearrangements (

21).

Nonossifying fibromas may be multiple in a large percentage of cases and, because of the occasional association with café-au-lait spots, may be confused with other entities, including polyostotic fibrous dysplasia and neurofibromatosis. Fibrous dysplasia characteristically has cutaneous pigmentation with a rugged or ragged border, so-called coast of Maine. In neurofibromatosis, café-au-lait spots are characterized by a smoother configuration, so-called coast of California. Nonossifying fibromas may be associated with either condition.

Eponyms associated with NOF and café-au-lait spots include one coined by Mirra (

22), termed Jaffe-Campanacci syndrome, a syndrome that includes multiple NOFs of the mandible, café-au-lait spots, endocrine disorders, mental retardation, ocular anomalies, and cardiovascular malformations (

23). The diagnosis of Jaffe-Campanacci syndrome, usually made in the peripuberty years, can be made by identifying smooth-bordered (coast of California) café-au-lait spots and axillary freckling in association with multiple NOFs without any evidence of neurofibromas (

23). “Fibrous cortical defects,” a term used by radiologists, is thought to be the same lesion as NOF, and is distinguished by its smaller size and frequent spontaneous sclerosis earlier in childhood than NOF.

Asymptomatic FMDs do not need to be treated. Large lesions with imminent fracture may require curettage and bone grafting.

Benign Fibrous Histiocytoma of Bone

Although benign fibrous histiocytoma (BFH) is a tumor that is well described in the soft tissue, it less commonly involves bone and, where encountered, bears a striking resemblance in its histologic appearance to the developmental abnormality FMD. It is distinguished from FMD by the atypical location in bone (not limited to metaphysis), more frequent occurrence outside the lower extremity, and occurrence in older patients. The majority of BFHs of bone involve long tubular bones, but they may also occur in other sites such as the spine, pelvis, and ribs, distinctly unusual locations for FMDs (

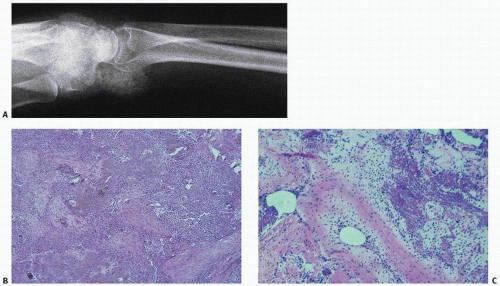

24) (

Fig. 8.10). Radiographically, BFH is a well-defined, lytic expansile lesion with little periosteal reaction. Internal trabeculations and sclerotic margins may be seen (

Fig. 8.10). Bone scintigraphy has been reported mildly positive, and MRI images reveal a T1-weighted signal similar to skeletal muscle (

25).

BFH occurs in adults between the third and sixth decades. It is characterized histologically by the proliferation of fibroblasts and histiocytes, usually in a swirling or storiform pattern, often admixed with foam cells, lipophages, and multinucleated giant cells. The foam cells may be prominent, giving a yellow gross appearance to the tumor. The lesions may be painful. Because of its distinct clinical differences, BFH is considered a benign tumor that can be locally aggressive and can even recur following curettage.

Of note in discussing the differentiation between BFH, considered a tumor of bone, and NOF, considered a developmental problem, is the recognition in tissue pathology of a broad range of disorders that may be characterized by the same heterogeneous population of cells. For example, histiocytes may be of metabolic (as in Gaucher disease), inflammatory, reactive, or neoplastic origin. The spectrum of change and clinical possibilities requires careful clinical, roentgenographic, and pathologic correlation.

BFH is considered a true neoplasm and may behave aggressively at the local site of involvement. Because recurrence may follow curettage, a margin of normal bone should be removed to avoid recurrence (

26).

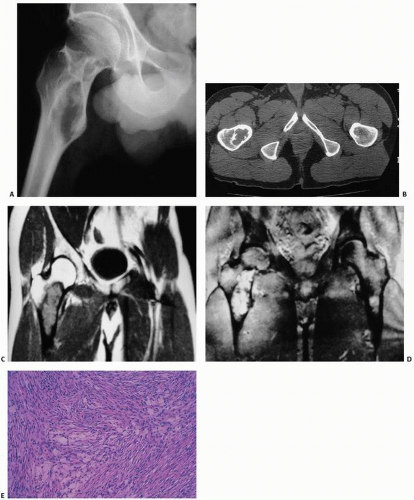

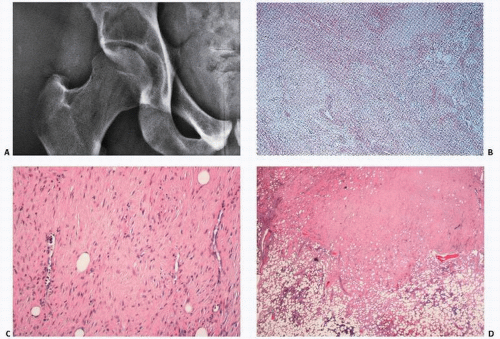

Desmoplastic Fibroma of Bone

Initially described by Cappell in 1935 in the fibula as an endosteal fibroma, Jaffe popularized the term “desmoplastic fibroma” a quarter of a century later for benign fibrous lesions arising within the bone with histologic characteristics of the extraosseous desmoid tumors. Desmoplastic fibroma has been considered to be the bony counterpart of the more common desmoid-type fibromatosis of soft tissue based on its characteristic long-sweeping blandly cellular fascicles of myofibroblastic cells. Recent genetic studies, however, question this association (vida infra).This rare, locally aggressive benign lesion may be extremely difficult to differentiate histologically from desmoids and low-grade fibrosarcomas and even fibrous histiocytoma, but combined characteristic pathologic and roentgenographic features can distinguish this lesion.

Desmoplastic fibroma is a rare, locally aggressive solitary tumor with a reported incidence of 0.06 percent to 0.11 percent of primary bone tumors (

27).

It tends to be diagnosed in the first three decades of life, with no sexual predilection, and most commonly presenting in the ilium, long bones, and mandible (

Fig. 8.11). Any flat bone may be involved, including the scapula, rib, and clavicle. Because of its insidious onset, the lesion is usually large at the time of clinical diagnosis, with only slight pain on occasion. Rarely, a pathologic

fracture may be the presenting symptom. Roentgenographically, these lesions are usually distinct, expansile, lucent lesions with well-defined margins (

Fig. 8.12). Cortical erosion with pathologic fracture may be seen. CT scans may show evidence of soft tissue invasion where involved. Desmoplastic fibroma appears well defined on MR images, revealing a low signal intensity on T1. T2-weighted images show low to intermediate signal. The clear separation of intraosseous tumor from normal bone marrow and extent of soft tissue involvement makes MRI extremely valuable in planning surgery. Histologically, the lesions are essentially identical to that of the desmoid tumor and are characterized by dense, collagenized tissue within which are uniform-appearing, benign fibroblasts. Although cellularity may vary within the lesion, the cells are almost always small and regular with bland nuclei and little hyperchromasia and mitotic activity. There are usually no giant cells. On microscopy alone, the distinction between a desmoplastic fibroma and desmoids, low-grade fibrosarcoma, and even fibrous histiocytoma may be very difficult. Special flow cytometric and histologic techniques have revealed diploid DNA ploidy, averaged 23 mean proliferative cell indices. Mitoses are rare. Mast cells may be seen.

Immunohistochemically, there is a variable degree of staining for smooth muscle actin, pan muscle actin, desmin, and cyclin D1. Nuclear β-catenin is occasionally present, but this is generally in less than 10 percent of the cells. Immunoexpression of MDM2 and CDK4 is also negative, in distinct contrast to low-grade central osteosarcoma.

The clinical course is that of local aggression with recurrence in up to 72 percent after nonresection procedures, 17 percent with resections, and 0 percent when resected with a wide surgical margin (

27). Therefore, recurrence may be avoided by a good surgical margin. Metastases have been reported after local recurrence in 3 of 184 cases (1.6 percent) reported in the literature. Recurrences range from 9 months to 11 years (average, 2.7 years). It is recommended that 3 years be the minimum follow-up period for evaluation of the efficacy of therapy (

27). Recurrences in the extremities have led to amputations in 25 percent of cases (

27).

The involvement of the APC/β catenin pathway in various fibromatoses has raised questions regarding whether desmoplastic fibroma shares these alterations. However, whereas nuclear β-catenin expression appears relatively specific for fibromatosis (nuclear overexpression of β-catenin protein is seen in more than 90 percent of fibromatoses), comparable degrees of these APC gene mutations have not been observed in desmoplastic fibroma (

28,

29).

In contrast to desmoid-type fibromatosis of soft tissue, no mutations are found in exon 3 of CTNNB1, encoding β-catenin. Thus, genetically there is little evidence to consider desmoplastic fibroma as the intraosseous counterpart of desmoid-type fibromatosis. Some cases show a trisomy of 8 and 20.

Fibromyxoid Tumors of Bone

Fibrous tumors of both soft tissue and bone may reveal focal “myxoid” histologic features characterized by stellate-shaped cells in a loose clear, gelatinous, or myxoid connective matrix background. The significance of this component is unclear, but has nonetheless lent itself to additional classifications of lesions including fibromyxoma of bone (

30,

31), which is similar to chondromyxoid fibroma of bone. In “fibromyxoma,” there is usually a distinct lytic lesion, which, although contained by the periosteum, may erode the cortex. These tumors tend to have light gray color with rubbery consistency, and histologically show proliferation of bland fibrous tissues and areas characterized by clear stellate cells in a myxoid stroma, thus giving rise to the term. Hemorrhage and necrosis may be seen, but not the lobulated pattern that is typical of chondromyxoid fibroma, which also contains large areas of cartilage. Other variants on this lesion have been described, including ossifying fibromyxoid tumor of soft parts (

32).