(1)

Department of Pathology, Radboud University Nijmegen Medical Center, Nijmegen, The Netherlands

Keywords

JawSinonasal CavitiesFibro-osseous Lesion7.1 Introduction

The current classification of maxillofacial fibro-osseous lesions includes fibrous dysplasia, ossifying fibroma and osseous dysplasia [1, 2]. In previous classifications, efforts to discern between bone and cementum caused designations as cement-ossifying of cementifying fibroma or cemental dysplasia. However, none of the proposed differences between cementum and bone has withstood the test of time and therefore terms as cementifying or cemental have been dropped as unwanted and confusing [3].

All lesions to be discussed under the heading fibro-osseous are composed of bone and fibrous tissue. Sutural tissue that connects the several bones that make up the craniofacial skeleton is composed of the same two elements and may be a diagnostic pitfall if not recognized as a normal component of this anatomical area (Figs. 7.1 and 7.2)

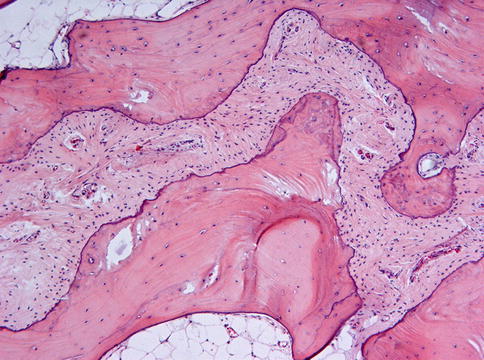

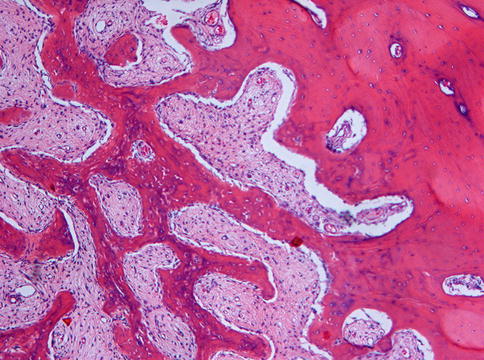

Fig. 7.1

Low power view of normal sutural tissue. Fibrous tissue connects trabeculae of lamellar bone. This normal anatomical structure should not be mistaken for a fibro-osseous lesion

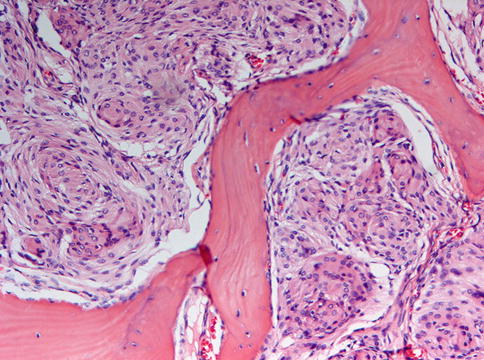

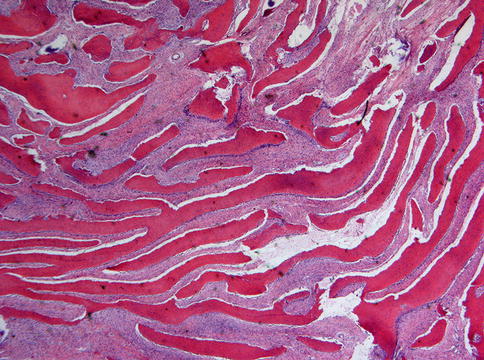

Fig. 7.2

Higher magnification of Fig. 7.1 to illustrate the mature lamellar nature of the two opposing bones that are connected by fibrocellular soft tissue

7.2 Fibrous Dysplasia

Fibrous dysplasia is composed of cellular fibrous tissue containing trabeculae mainly consisting of woven bone. It occurs in three clinical subtypes: monostotic which affects one bone, polyostotic which affects multiple bones, and Albright’s syndrome in which multiple bone lesions are accompanied by skin hyperpigmentation and endocrine disturbances [1]. Activating missense mutations of the gene encoding the α subunit of the stimulatory G protein are a consistent finding in the various forms of fibrous dysplasia [4].

Craniofacial fibrous dysplasia usually is of the monostotic type [5]. Mostly, the disease occurs during the first three decades although occasionally, cases are seen at an older age. The maxilla is more often involved than the mandible [1]. Usually, fibrous dysplasia clinically presents itself as a painless swelling of the involved bone. Radiographically, the classical appearance is described as orange-skin or ground-glass radiopacity without defined borders [1]. In the maxilla, fibrous dysplasia may extend by continuity across suture lines to involve adjacent bones which is a very important radiologic diagnostic tool (Fig. 7.3).

Fig. 7.3

Radiograph showing diffuse enlargement with ground glass appearance involving both maxilla and zygomatic arch. Such an involvement of adjacent bones indicating that the disease crosses sutures is highly characteristic for fibrous dyplasia

Microscopically, fibrous dysplasia shows replacement of the normal bone by moderately cellular fibrous tissue containing irregularly shaped trabeculae of varying width and consisting of woven bone that may form a lattice (Figs. 7.4 and 7.5). Occasionally, more spherical bony deposits can be seen (Fig. 7.6); osteoblastic activity typically is absent (Figs. 7.7 and 7.8). At the periphery lesional bone is seen to fuse with adjacent bone (Figs. 7.9 and 7.10). Jaw lesions, especially those occurring in the posterior maxilla, may also show lamellar bone which may be accompanied with a specific pattern of the bony trabeculae mimicking a fingerprint (Figs. 7.11, 7.12 and 7.13). Sometimes, tiny calcified spherules may be present which occasionally may be rather numerous (Figs. 7.14 and 7.15) [6].

Fig. 7.4

Low power view to show slender curvilinear trabeculae in a moderately cellular fibrous background

Fig. 7.5

Occasionally, the bony trabeculae in fibrous dysplasia may fuse to form a lattice

Fig. 7.6

In some cases of fibrous dysplasia, the bony particles may be not slender but spherical

Fig. 7.7

Photomicrograph of fibrous dysplasia to show the absence of any osteoblasts at the border between bone and fibrocellular tissue. Osteocyte lacunae with nuclear contents however are a very prominent feature

Fig. 7.8

High power view of the interface between bone and fibrocellular tissue. The fibroblasts are gradually transformed into osteocytes by osteoid deposition. However, no osteoblasts are present

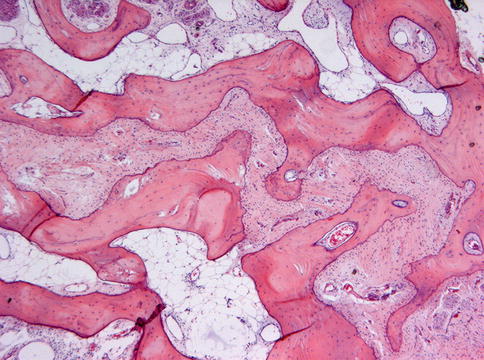

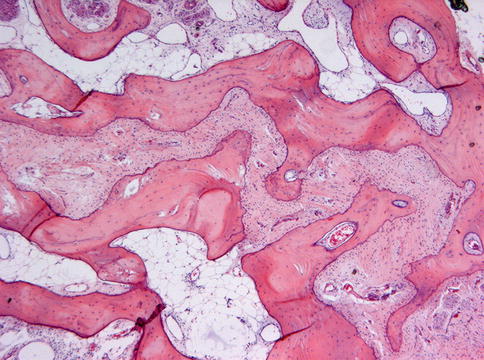

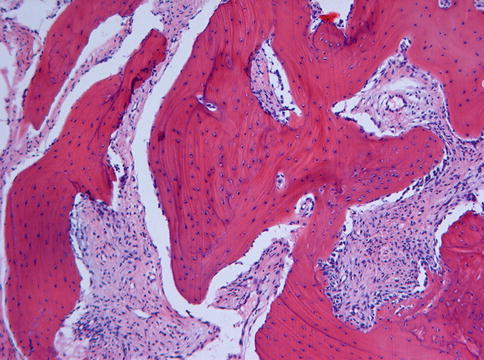

Fig. 7.9

Low power view to show that the bone in fibrous dysplasia merges with adjacent cancellous and cortical lamellar bone which is a very important histologic feature to distinguish fibrous dysplasia from other fibro-osseous jaw lesions

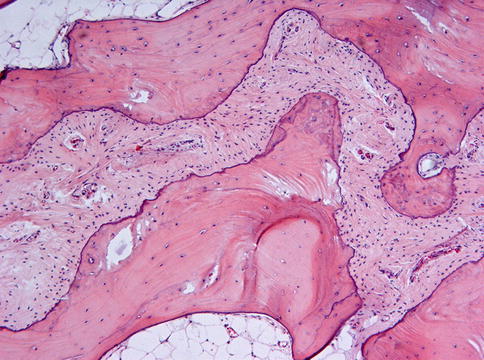

Fig. 7.10

At higher magnification, the fusion of trabeculae of woven bone in fibrous dysplasia with adjacent lamellar bone is clearly visible

Fig. 7.11

Radiograph showing radiodense lesion in the posterior right maxilla. Homogeneous appearance suggests fibrous dysplasia. Cases in this area may show lamellar maturation

Fig. 7.12

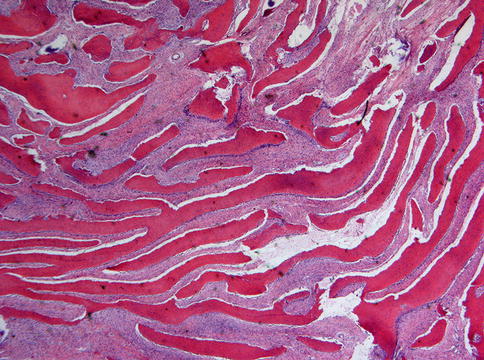

In the posterior maxilla, slightly curved trabeculae may lie parallel to each other thus showing a fingerprint-like pattern

Fig. 7.13

In addition to the fingerprint-like architecture illustrated in Fig. 7.12, posterior maxilla cases of fibrous dysplasia also may show some lamellar maturation

Fig. 7.14

Occasionally, some tiny calcified spherules can be found in cases of fibrous dysplasia

Fig. 7.15

Fibrous dysplasia also may show more rounded bony as well as acellular basophilic particles

Fibrous dysplasia may be confused with other lesions characterized by the combination of fibrous tissue and bone: ossifying fibroma, osseous dysplasia, low grade osteosarcoma and sclerosing osteomyelitis. However, none of these is exclusively composed of woven bone trabeculae fusing with adjacent uninvolved bone. Ossifying fibroma and osseous dysplasia both show much variety in appearances of mineralized material and stromal cellularity and in case of ossifying fibroma, there is a clear demarcation from surrounding tissue, often even a capsule. Low grade osteosarcoma invades through the cortical bone into adjacent soft tissues and sclerosing osteomyelitis shows coarse trabeculae of lamellar bone whereas the intervening stroma is not cellular but edematous with sprinkled lymphocytes [2].

Sometimes, focal hemorrhage with clustering of osteoclastic giant cells may lead to confusion with central giant cell granuloma, especially if there is excessive metaplastic bone formation in the latter. However, in all equivocal cases, detection of the diagnostic mutation will be decisive provided that undecalcified or EDTA decalcified material is available [7].

Radiological mimics of fibrous dysplasia are meningioma with hyperostosis as may occur in the walls of the paranasal sinuses (Figs. 7.16 and 7.17) [8] and intraosseous hemangioma that occasionally may be accompanied with excessive reactive bone formation (Fig. 7.18) [9]. Both are easily to distinguish from fibrous dysplasia as histologically, they do not show any overlapping features.

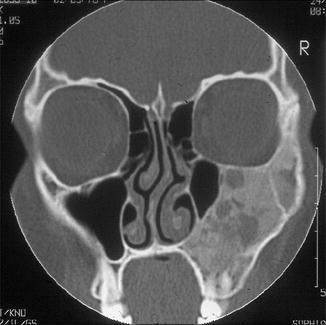

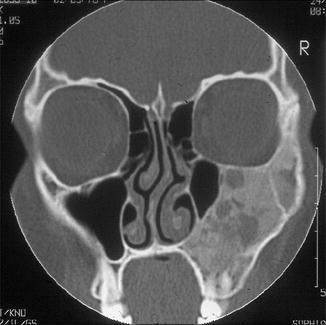

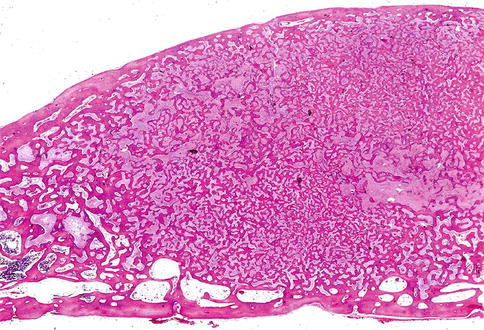

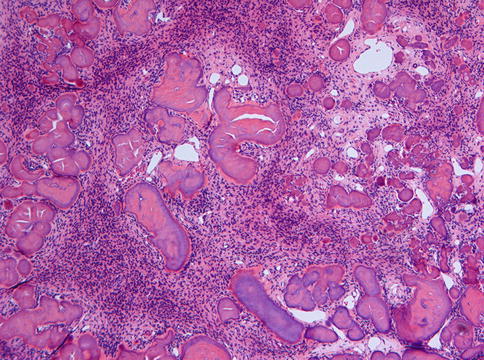

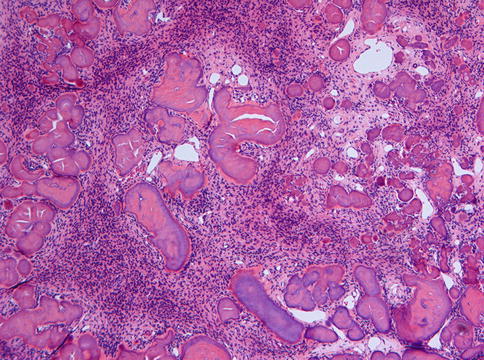

Fig. 7.16

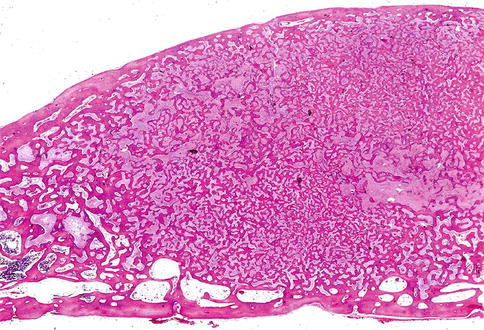

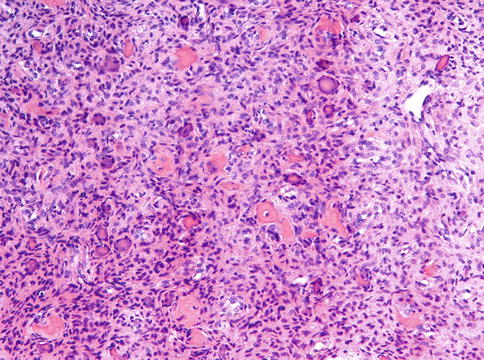

Bone marrow spaces containing meningioma. Radiologically, concomitant bone formation may mimic fibrous dysplasia

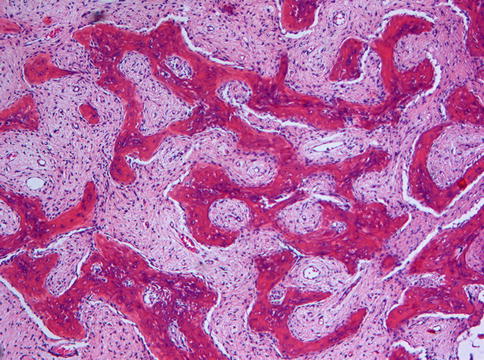

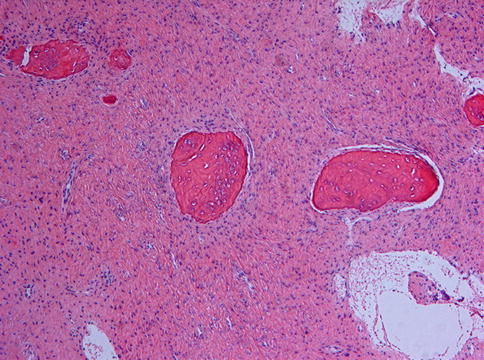

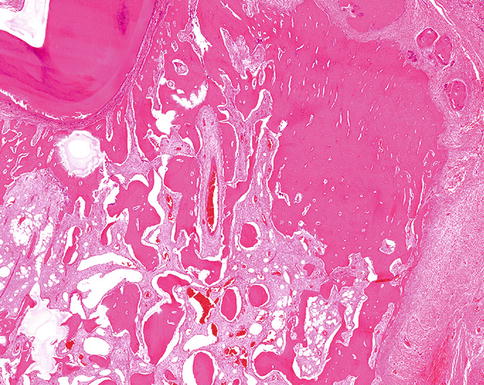

Fig. 7.18

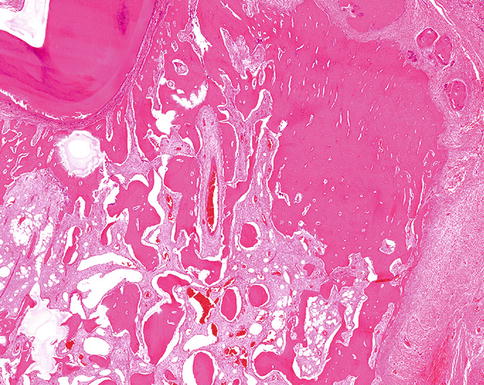

Hemangioma may induce bone formation which also may mimic fibrous dysplasia at the radiographic imaging

Other entities occurring in the head and neck area that may mimic fibrous dysplasia radiologically are the so-called “Bullough lesion” and odontomaxillary dysplasia. Both entities have already been discussed in Chap. 1. Bullough lesion is a lesion at the surface of the temporal bone and characterized histologically by rounded and ovoid zones of ossification within a bland fibrous stroma and so is different from fibrous dysplasia both by its location and histology whereas odontomaxillary dysplasia is different from fibrous dysplasia with thickened, irregularly shaped trabeculae of immature woven bone with bone marrow spaces changed into loose paucicellular fibrous tissue [10, 11].

Usually, fibrous dysplasia is a self-limiting disease. Therefore, treatment is only required in case of problems due to local increase in size of the affected bone, especially when there is impairment of nerve function which may occur if there is involvement of skull base of temporal bone. Sometimes, an osteosarcoma may arise in fibrous dysplasia [12].

7.3 Ossifying Fibroma

Ossifying fibroma , formerly also called cemento-ossifying fibroma is a well-demarcated lesion composed of fibrocellular tissue and mineralized material of varying appearances. The lesion occurs most often in the second through fourth decades and there is a predilection for females. The posterior mandible is the favored site [1] and occasionally, patients may suffer from multiple lesions [13]. In those cases, the possibility of hyperparathyroidism-jaw tumor syndrome has to be considered, an autosomal dominant syndrome characterized by primary hyperparathyroidism (PHPT) with multiple parathyroid adenomas occurring at an early age with increased risk for parathyroid carcinoma, fibro-osseous jaw lesions, and renal cysts or tumors [14].

Clinically, ossifying fibroma causes expansion of the involved bone leading to a palpable swelling and radiographically one sees a demarcated lesion that may have radiodense as well as radiolucent areas depending on the various contributions of soft and hard tissue components to an individual lesion (Figs. 7.19, 7.20 and 7.21) [1].

Fig. 7.19

Mainly radiolucent ossifying fibroma due to paucity of mineralized material. The expansive nature of the lesion is manifest by the bulging of the lower cortex and the displacement of adjacent teeth

Fig. 7.20

Mixed radiodense and radiolucent ossifying fibroma. The demarcation from the surrounding tissue allows differentiation form fibrous dysplasia

Fig. 7.21

Cut surface of mandibular ossifying fibroma. Several teeth lie embedded in the tumor mass

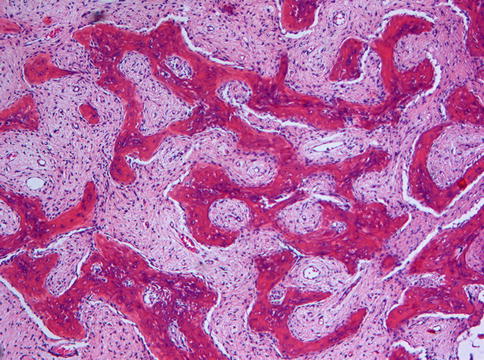

Microscopically, ossifying fibroma is composed of fibrous tissue that may vary in cellularity from areas with closely packed cells displaying mitotic figures to almost acellular scleroting parts within one and the same lesion. The mineralized component may consist of plexiform bone, lamellar bone and acellular mineralized material, all sometimes occurring together in one single lesion. The broad variation in morphology of mineralized deposits as well as in cellularity in ossifying fibroma is illustrated in Figs. 7.22, 7.23, 7.24, 7.25, 7.26, 7.27, 7.28, 7.29 and 7.30. Lesions show a sharp demarcation from their surroundings, either through a fibrous capsule or by a rim of adjacent bone showing remodeling activity (Figs. 7.31 and 7.32) but this feature may not always be apparent when samples submitted for histology do not include the border between the lesion and the adjacent tissue.

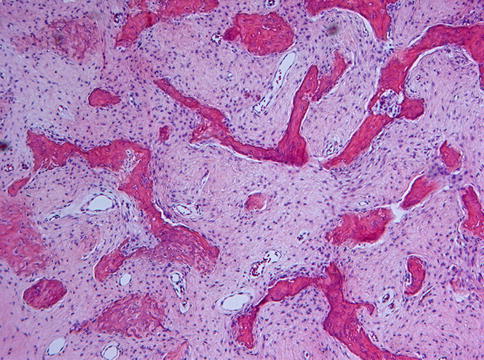

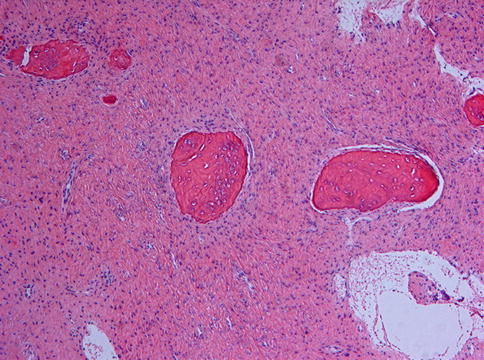

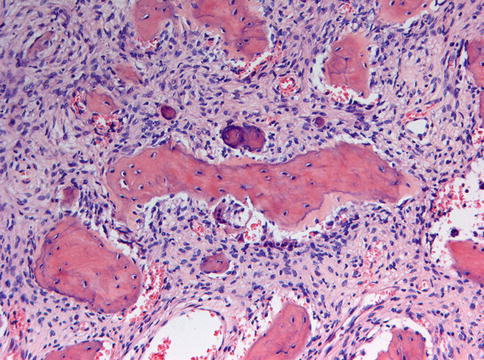

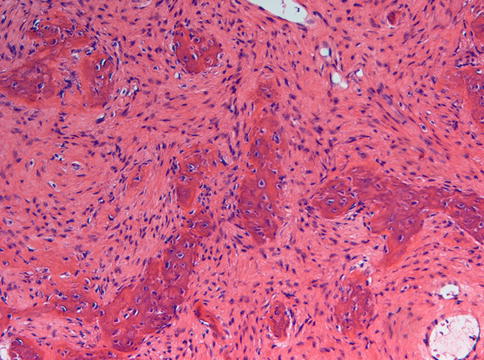

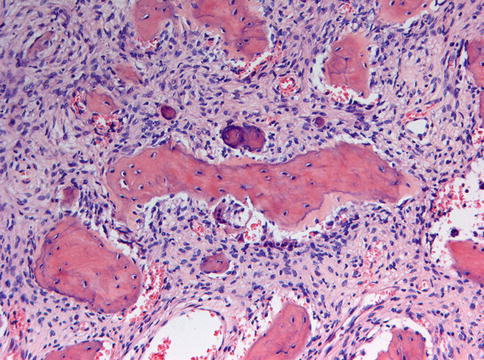

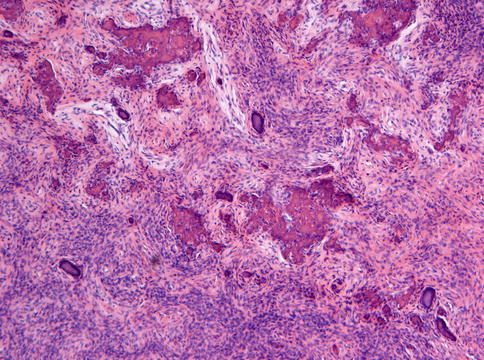

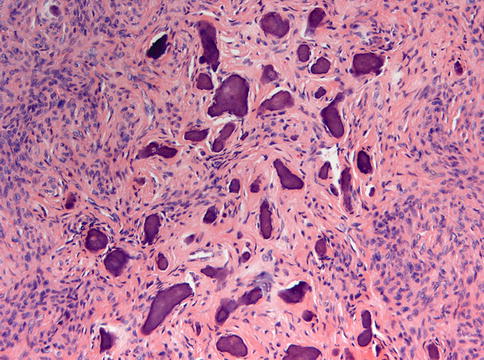

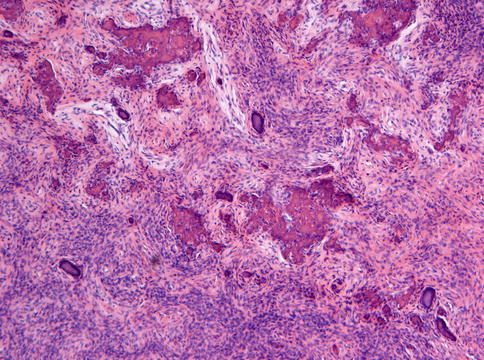

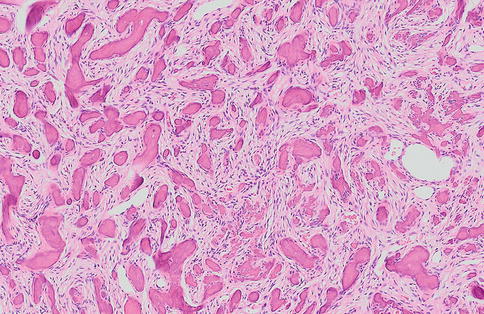

Fig. 7.22

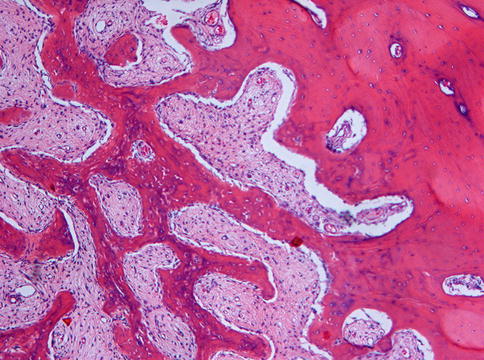

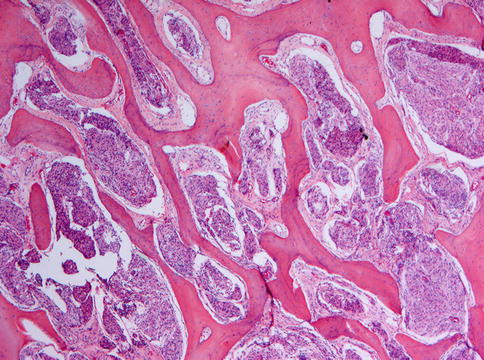

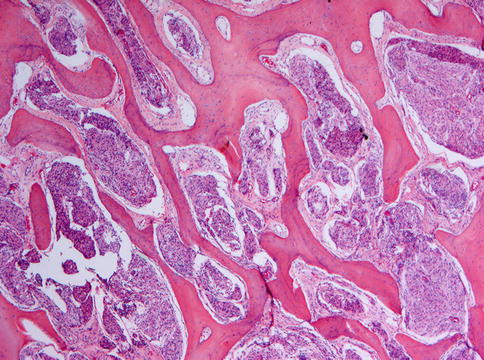

Ossifying fibroma characterized by fibrous tissue of varying cellularity and containing irregular fragments of woven bone as well as acellular mineralized deposits

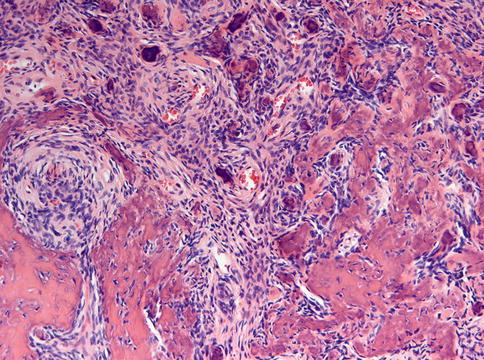

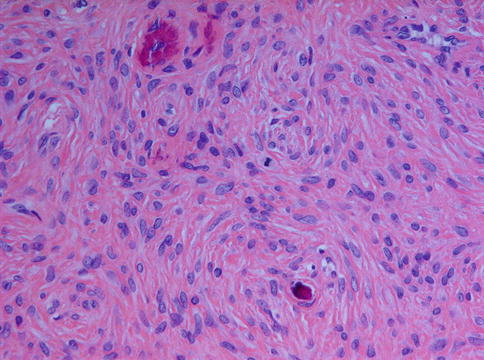

Fig. 7.23

Higher magnification from Fig. 7.22 to illustrate the osteoblastic lining of the bony trabeculae which is one of the morphological features to differentiate between ossifying fibroma and fibrous dysplasia

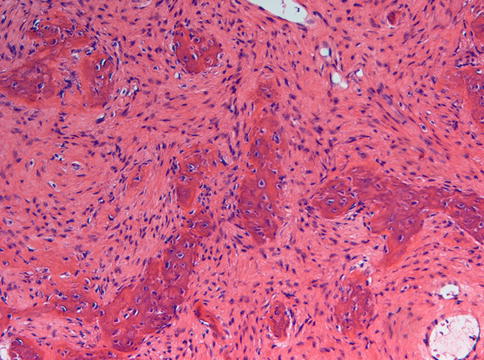

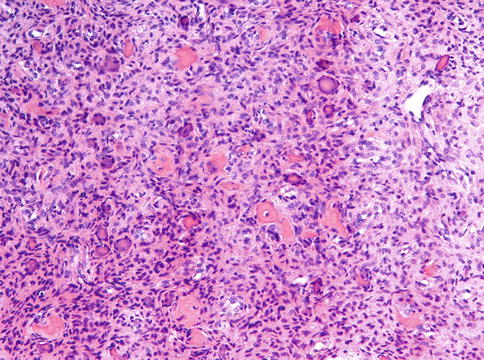

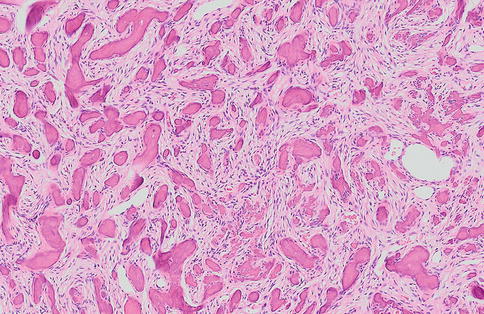

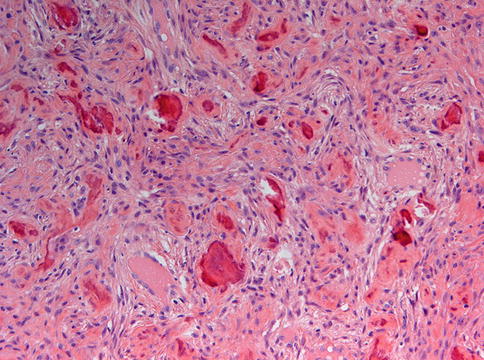

Fig. 7.24

Ossifying fibroma containing small bony particles, mainly acellular and with an irregular outline

Fig. 7.25

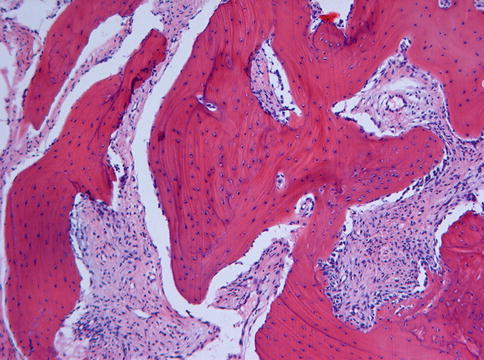

Ossifying fibroma with a predominance of acellular bony deposits

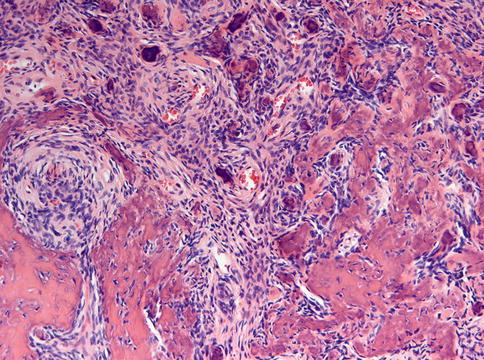

Fig. 7.26

Ossifying fibroma with closely packed acellular bony deposits and mainly fibrous stroma

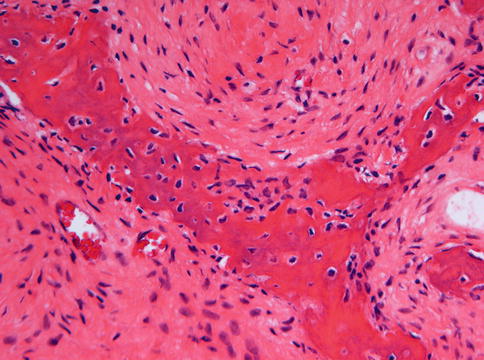

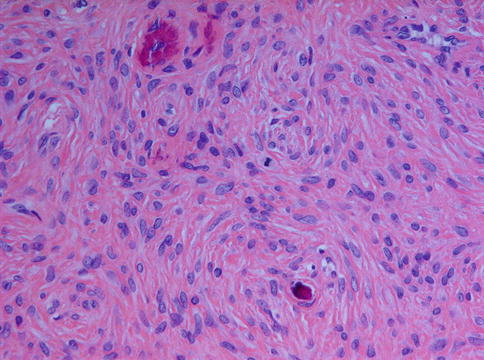

Fig. 7.27

An occasional mitotic figure may be present in ossifying fibroma

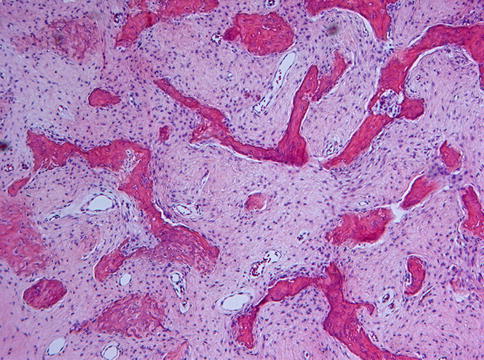

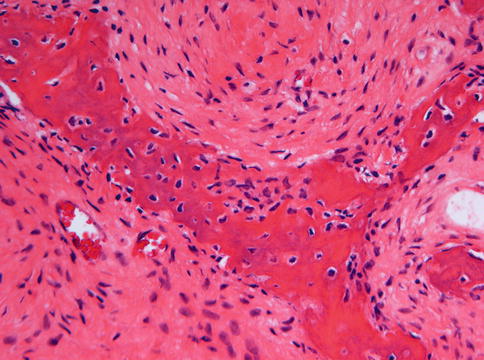

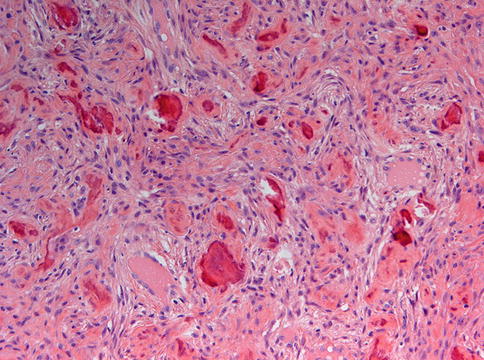

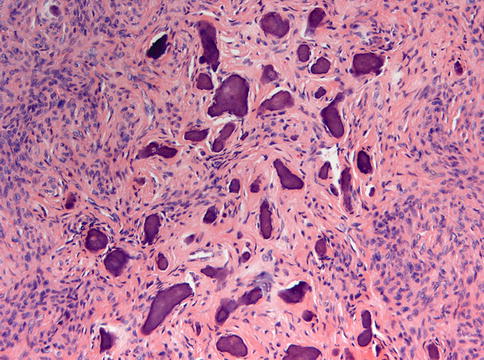

Fig. 7.28

Ossifying fibroma with acellular smoothly outlined bony masses and highly cellular stroma background. In the past, this pattern was considered to be typical for cementifying fibroma but this designation has been dropped as there are no reliable criteria to distinguish between bone and cementum other than the location, cementum by definition a tissue covering the roots of a tooth

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree