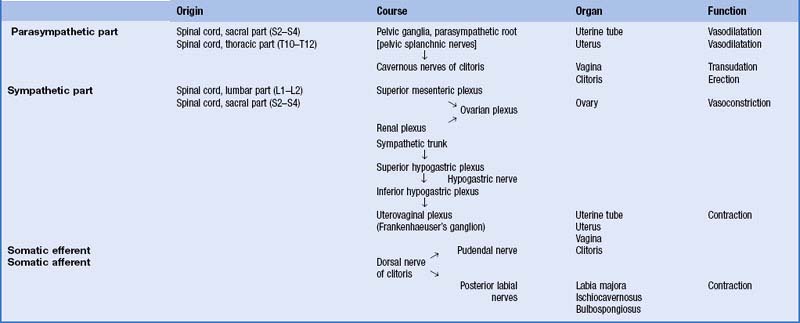

CHAPTER 77 Female reproductive system

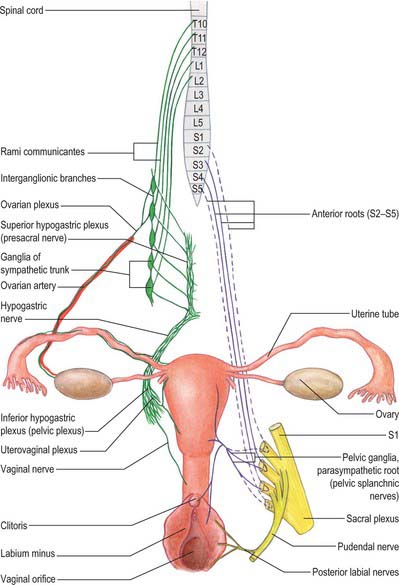

The female reproductive system consists of the lower genital tract (vulva and vagina) and the upper tract (uterus and cervix with associated uterine (Fallopian) tubes and ovaries).

LOWER GENITAL TRACT

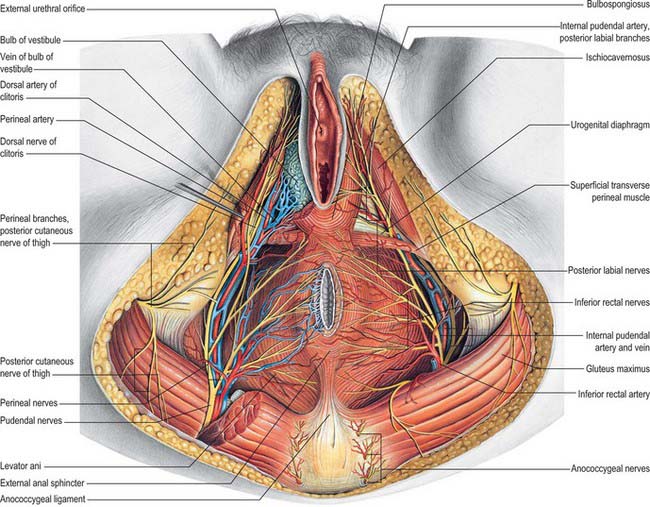

VULVA

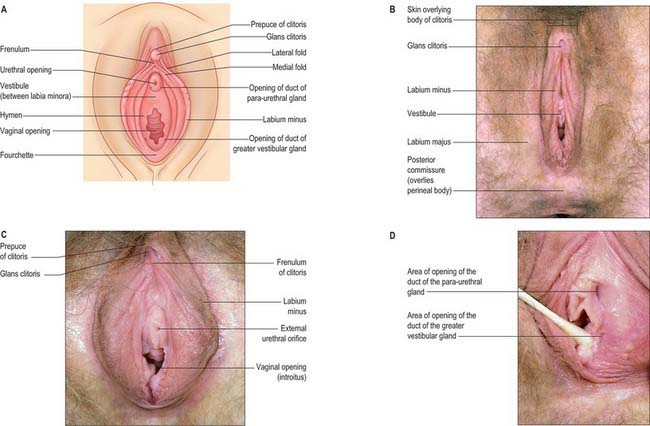

The female external genitalia or vulva include the mons pubis, labia majora, labia minora, clitoris, vestibule, vestibular bulb and the greater vestibular glands (Fig. 77.1A–D).

Labia majora

The labia majora are two prominent, longitudinal folds of skin that extend back from the mons pubis to the perineum (Fig. 77.1B). They form the lateral boundaries of the vulva. Each labium has an external, pigmented surface covered with hairs and a smooth, pink internal surface with large sebaceous follicles. Between these surfaces there is loose connective and adipose tissue, intermixed with smooth muscle (resembling the scrotal dartos muscle), vessels, nerves and glands. The uterine round ligament may end in the adipose tissue and skin in the anterior part of the labium. A persistent processus vaginalis and congenital inguinal hernia may also reach a labium. The labia are thicker anteriorly, where they join to form the anterior commissure. Posteriorly they do not join, but instead merge into neighbouring skin, ending near and almost parallel to each other. The connecting skin between them posteriorly forms a ridge, the posterior commissure, that overlies the perineal body and is the posterior limit of the vulva. The distance between this and the anus is 2.5–3 cm thick and is termed the ‘gynaecological’ perineum.

Labia minora

The labia minora are two small cutaneous folds, devoid of fat, that lie between the labia majora. They extend from the clitoris obliquely down, laterally and back, flanking the vaginal orifice. Anteriorly, each labium minus bifurcates. The upper layer of each side passes above the clitoris to form a fold, the hood or prepuce, which overhangs the glans of the clitoris. The lower layer of each side passes below the clitoris to form the frenulum of the clitoris (Fig. 77.1A,C). Sebaceous follicles are numerous on the apposed labial surfaces. Sometimes an extra labial fold (labium tertium) is found on one or both sides between the labia minora and majora.

Vestibule

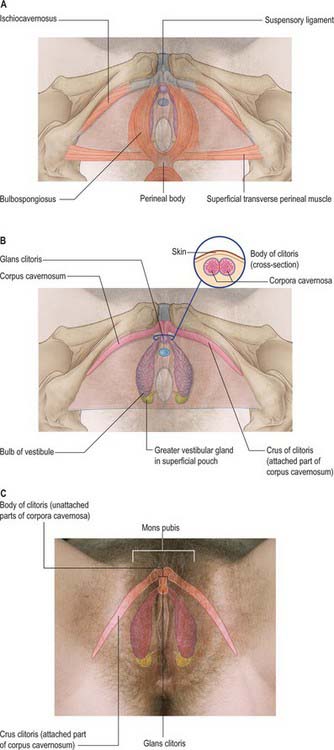

Bulbs of the vestibule

The bulbs of the vestibule lie on each side of the vestibule. They are two elongated masses of erectile tissue, 3 cm long, which flank the vaginal orifice and unite anterior to it by a narrow commissura bulborum (pars intermedia). Their posterior ends are expanded and are in contact with the greater vestibular glands. Their anterior ends taper and are joined by a commissure and also to the clitoris by two slender bands of erectile tissue. Their deep surfaces contact the inferior aspect of the urogenital diaphragm, and superficially each is covered by bulbospongiosus posteriorly (Fig. 77.2A–C).

Greater vestibular glands (Bartholin’s glands)

The greater vestibular glands are homologues of the male bulbourethral glands. They consist of two small, round or oval, reddish-yellow bodies that flank the vaginal orifice, in contact with, and often overlapped by, the posterior end of the vestibular bulb. Each opens into the postero-lateral part of the vestibule by a 2 cm duct, situated in the groove between the hymen and the labium minus (Fig. 77.1D). The glands are composed of tubulo-acinar tissue. The secretory cells are columnar and secrete a clear or whitish mucus with lubricant properties. They are stimulated by sexual arousal.

Clitoris

The clitoris is an erectile structure partially enclosed by the anterior bifurcated ends of the labia minora. It has a root, a body, and a glans. The body can be palpated through the skin. It contains two corpora cavernosa, composed of erectile tissue and enclosed in dense fibrous tissue, and separated medially by an incomplete fibrous pectiniform septum. The fibrous tissue forms a suspensory ligament that is attached superiorly to the pubic symphysis. Each corpus cavernosum is attached to its ischiopubic ramus by a crus that extends from the root of the clitoris. The glans clitoris is a small round tubercle of spongy erectile tissue at the end of the body and connected to the bulbs of the vestibule by thin bands of erectile tissue. It is exposed between the anterior ends of the labia minora. Its epithelium has high cutaneous sensitivity, important in sexual responses (Fig. 77.2).

Vascular supply and lymphatic drainage of the vulva

Arteries

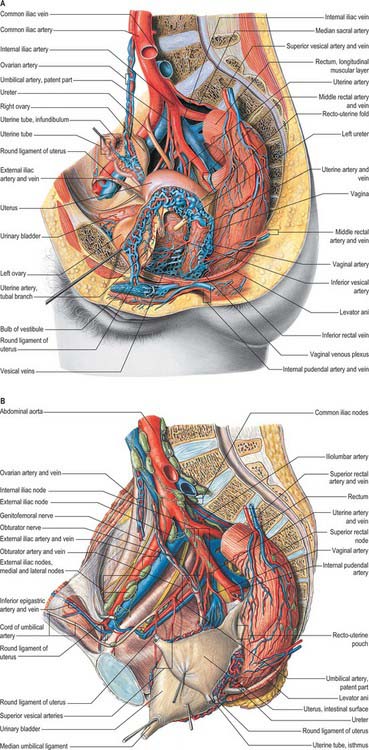

The arterial blood supply of the female external genitalia is derived from the superficial and deep external pudendal branches of the femoral artery and the internal pudendal artery on each side (Fig. 77.3A).

Veins

Venous drainage of the vulval skin is via external pudendal veins to the long saphenous vein. Venous drainage of the clitoris is via deep dorsal veins to the internal pudendal vein and superficial dorsal veins to the external pudendal and long saphenous veins (Fig. 77.3A).

Lymphatic drainage

A meshwork of connecting vessels join to form three or four collecting trunks around the mons pubis which drain to superficial inguinal nodes lying on the cribriform fascia covering the femoral artery and vein; these nodes drain through the cribriform fascia to the deep inguinal nodes lying medial to the femoral vein. The deep inguinal nodes drain via the femoral canal to the pelvic nodes. The last of the deep inguinal nodes lies under the inguinal ligament within the femoral canal and is often called Cloquet’s node. Lymph vessels in the perineum and lower part of the labia majora drain to the rectal lymphatic plexus. Lymph vessels from the clitoris and labia minora drain to deep inguinal nodes and direct clitoral efferents may pass to the internal iliac nodes (Fig. 77.3B).

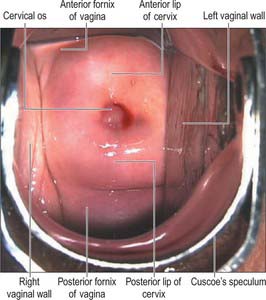

VAGINA

The vagina is a fibromuscular tube lined by non-keratinized stratified epithelium. It extends from the vestibule (the opening between the labia minora) to the uterus. The upper end of the vagina surrounds the vaginal projection of the uterine cervix. The annular recess between the cervix and vagina is the fornix: the different parts of this recess are given separate names, i.e. anterior, posterior and right and left lateral, but they are continuous (Fig. 77.6).

The vagina ascends posteriorly and superiorly at an angle of over 90° to the uterine axis: this angle varies with the contents of the bladder and rectum. The width of the vagina increases as it ascends. Above the level of the hymen, the inner surfaces of the anterior and posterior vaginal walls are ordinarily in contact with each other forming a transverse slit. The vaginal mucosa is attached to the uterine cervix higher on the posterior cervical wall than on the anterior: the anterior wall is approximately 7.5 cm long and the posterior wall is approximately 9 cm long. The anterior wall of the vagina is related to the base of the bladder in its middle and upper portions and to the urethra (which is embedded in it) inferiorly. The posterior wall is covered by peritoneum in its upper quarter. It is separated from the rectum by the recto-uterine pouch superiorly, and by moderately loose connective tissue (Denonvillier’s fascia) in its middle half. In its lower quarter it is separated from the anal canal by the musculofibrous perineal body. Laterally are levator ani and pelvic fascia (see Fig. 75.1A). As the ureters pass anteromedially to reach the fundus of the bladder, they pass close to the lateral fornices. As they enter the bladder the ureters are usually anterior to the vagina, and at this point, each ureter is crossed transversely by a uterine artery (Fig. 77.7).

Fig. 77.7 Relationship of the ureter to the uterine and vaginal arteries.

(From Drake, Vogl and Mitchell 2005.)

Remnants of the duct of Gartner (embryologically the caudal end of the mesonephric duct) (see Ch. 78), are occasionally seen protruding through the lateral fornices or lateral parts of the vagina; these can cause cysts (Gartner’s cysts).

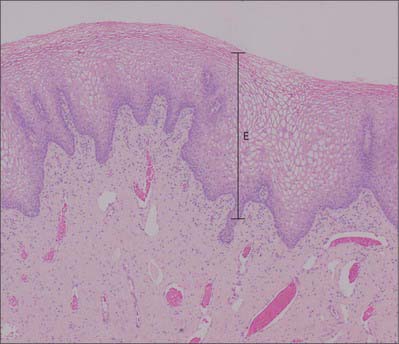

Microstructure

The vagina has an inner mucosal and an external muscular layer. The mucosa adheres firmly to the muscular layer. There are two median longitudinal ridges on its epithelial surface, one anterior and the other posterior. Numerous transverse bilateral rugae extend from these vaginal columns. They are divided by sulci of variable depth, giving an appearance of conical papillae, which are most numerous on the posterior wall and near the orifice, and which are especially well developed before parturition. The epithelium is non-keratinized, stratified, squamous similar to, and continuous with, that of the ectocervix. After puberty it thickens and its superficial cells accumulate glycogen, which gives them a clear appearance in histological preparations.

The vaginal epithelium does not change markedly during the menstrual cycle, but its glycogen content increases after ovulation and then diminishes towards the end of the cycle. Natural vaginal bacteria, particularly Lactobacillus acidophilus, break down glycogen in the desquamated cellular debris to lactic acid. This produces a highly acidic (pH 3) environment, which inhibits the growth of most other microorganisms. The amount of glycogen is less before puberty and after the menopause, when vaginal infections are more common. There are no mucous glands, but a fluid transudate from the lamina propria and mucus from the cervical glands lubricate the vagina (Fig. 77.8). The muscular layers are composed of smooth muscle and consist of a thick outer longitudinal and an inner circular layer. The two layers are not distinct but connected by oblique interlacing fibres. Longitudinal fibres are continuous with the superficial muscle fibres of the uterus. Half way along the vagina is a U-shaped muscular sling, called the pubo-vaginalis. The lower vagina is also surrounded by the skeletal muscle fibres of bulbospongiosus. A layer of loose connective tissue, containing extensive vascular plexuses, surrounds the muscle layers.

UPPER GENITAL TRACT

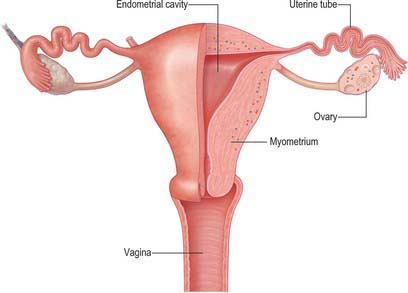

UTERUS

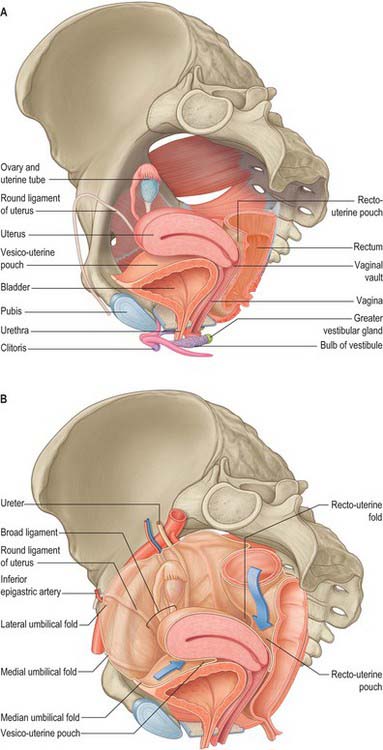

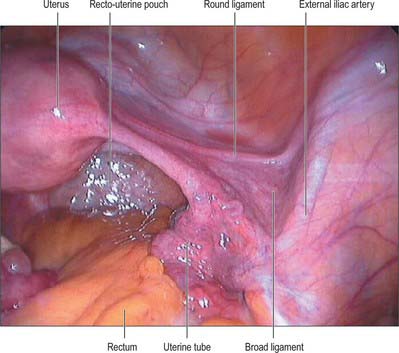

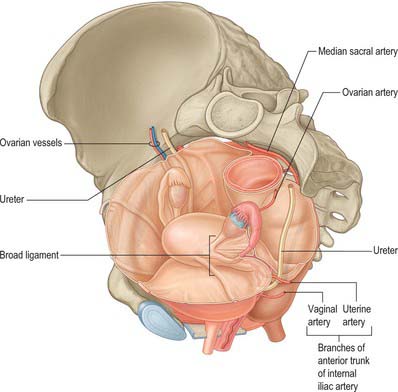

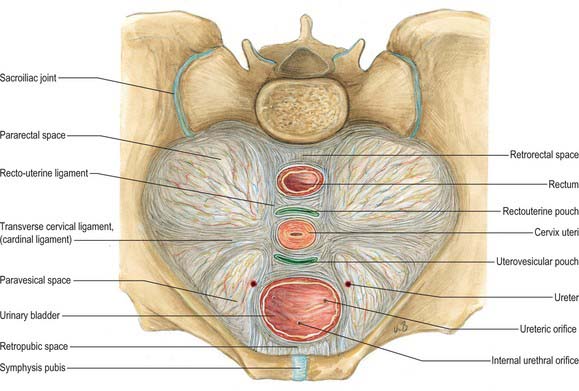

The uterus is a thick-walled, muscular organ situated in the pelvis between the urinary bladder and the rectum (Figs 77.9–77.11). It lies posterior to the bladder and uterovesical space and anterior to the rectum and recto-uterine pouch: it is mobile, which means that its position varies with distension of the bladder and rectum. The broad ligaments are lateral.

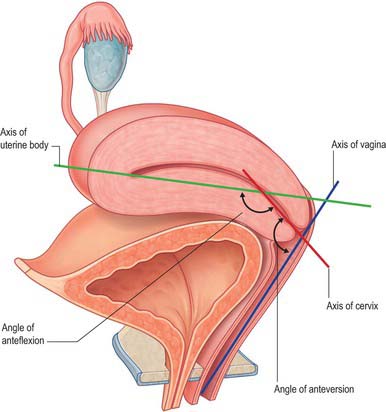

The uterus is divided into two main regions: the body of the uterus (corpus uteri) forms the upper two-thirds, and the cervix (cervix uteri) forms the lower third. In the adult nulliparous state the cervix tilts forwards relative to the axis of the vagina (anteversion), and the body of the uterus tilts forward relative to the cervix (anteflexion) (Fig. 77.12). In 10 to 15% of women the whole uterus leans backwards at an angle to the vagina and is said to be retroverted. A uterus that angles backwards on the cervix is described as retroflexed.

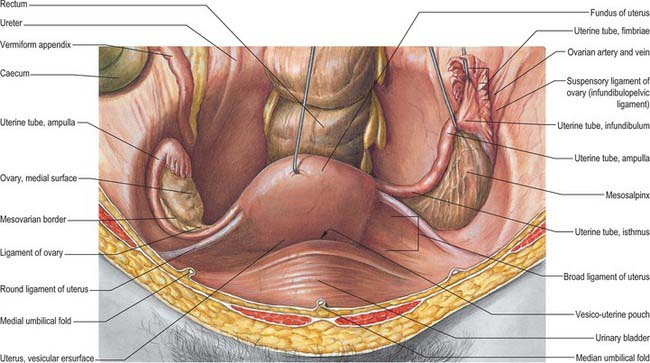

Body

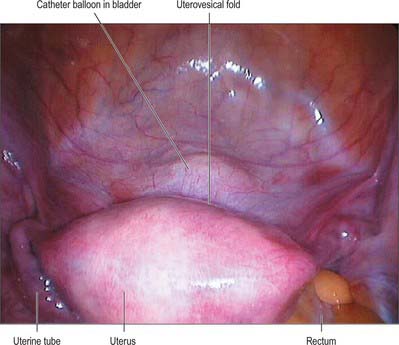

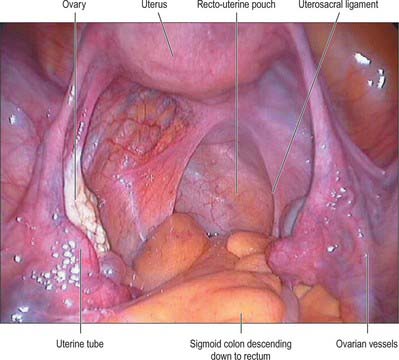

The body of the uterus is pear shaped and extends from the fundus superiorly to the cervix inferiorly. Near its upper end, the uterine tubes enter the uterus on both sides at the uterine cornua. Inferoanterior to each cornu is the round ligament and inferoposterior is the ovarian ligament. The dome-like fundus is superior to the entry points of the uterine tubes and covered by peritoneum which is continuous with that of neighbouring surfaces. The fundus is in contact with coils of small intestine and occasionally by distended sigmoid colon. The lateral margins of the body are convex, and on each side their peritoneum is reflected laterally to form the broad ligament, which extends as a flat sheet to the pelvic wall (Fig. 77.13). The anterior surface of the uterine body is covered by peritoneum which is reflected onto the bladder at the uterovesical fold (Fig. 77.14). This normally occurs at the level of the internal os, the most inferior margin of the body of the uterus. The vesico-uterine pouch between the bladder and uterus is obliterated when the bladder is distended, but may be occupied by small intestine when the bladder is empty. The posterior surface of the uterus is convex transversely. Its peritoneal covering continues down to the cervix and upper vagina and is then reflected back to the rectum along the surface of the recto-uterine pouch (of Douglas), which lies posterior to the uterus (Fig. 77.15). The sigmoid colon and occasionally the terminal ileum lie posterior to the uterus.

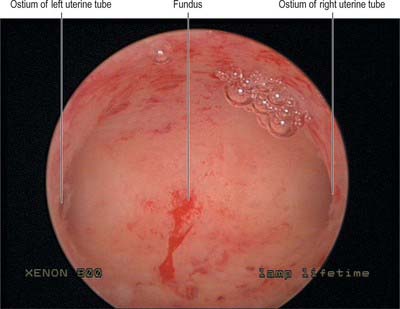

The cavity of the uterine body usually measures 6 cm from the external os of the cervix to the wall of the fundus and is flat in its anteroposterior plane. In coronal section, it is triangular, broad above where the two uterine tubes join the uterus, and narrow below at the internal os of the cervix (Fig. 77.16).

Cervix

The adult, non-pregnant cervix is narrower and more cylindrical than the body of the uterus and is typically 2.5 cm long. The upper end communicates with the uterine body via the internal os and the lower end opens into the vagina at the external os. In nulliparous women, the external os is usually a circular aperture, whereas after childbirth it is a transverse slit. Two longitudinal ridges, one each on its anterior and posterior walls, give off small oblique palmate folds that ascend laterally like the branches of a tree (arbor vitae uteri): the folds on opposing walls interdigitate to close the canal. The narrower isthmus forms the upper third of the cervix. Although unaffected in the first month of pregnancy, it is gradually taken up into the uterine body during the second month to form the ‘lower uterine segment’ (see below). In non-pregnant women the isthmus undergoes menstrual changes, although these are less pronounced than those occurring in the uterine body. The external end of the cervix enters the upper end of the vagina, thereby dividing the cervix into supravaginal and vaginal parts. The supravaginal part is separated anteriorly from the bladder by cellular connective tissue, the parametrium, which also passes to the sides of the cervix and laterally between the two layers of the broad ligaments.

Pelvic ligaments and peritoneal folds

Peritoneal folds

Uterovesical and rectovaginal folds

The anterior or uterovesical fold consists of peritoneum reflected onto the bladder from the uterus at the junction of its cervix and body. The posterior or rectovaginal fold consists of peritoneum reflected from the posterior vaginal fornix on to the front of the rectum, thereby create the deep recto-uterine pouch of Douglas. The pouch of Douglas is bounded anteriorly by the uterus, supravaginal cervix and posterior vaginal fornix, posteriorly by the rectum and laterally by the uterosacral ligaments.

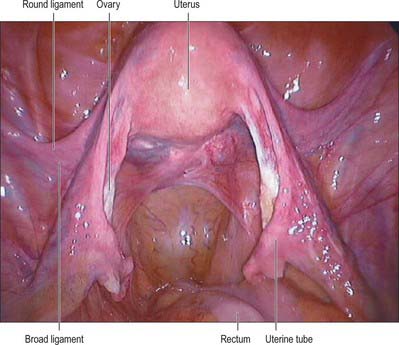

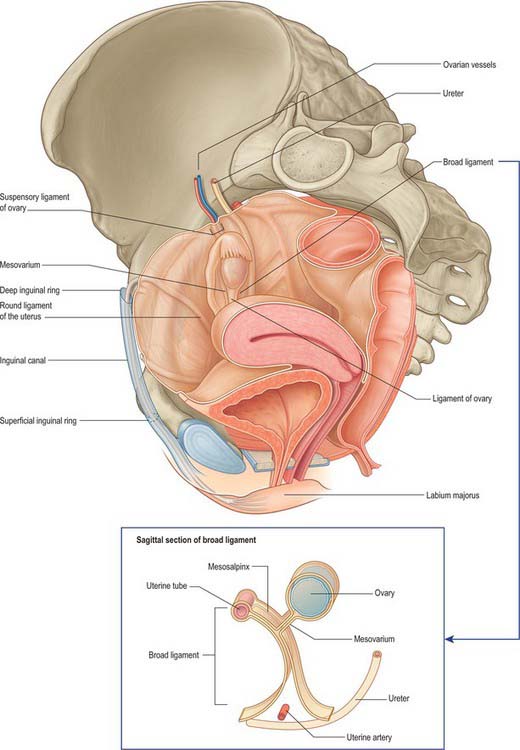

Broad ligament

The lateral folds or broad ligaments extend on each side from the uterus to the lateral pelvic walls, where they become continuous with the peritoneum covering those walls (Figs 77.17, 77.18). The upper border is free and the lower border is continuous with the peritoneum over the bladder, rectum and pelvic side-wall. The borders are continuous with each other at the free edge via the uterine fundus and diverge below near the superior surfaces of levatores ani. A uterine tube lies in the upper free border on either side. The broad ligament is divided into an upper mesosalpinx, a posterior mesovarium and an inferior mesometrium.

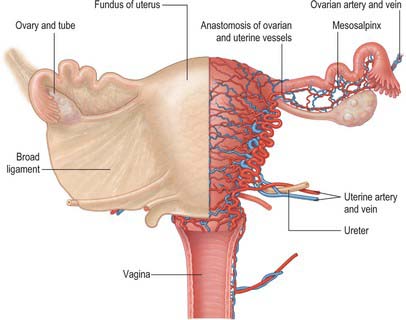

Fig. 77.17 Pelvic peritoneal reflections, demonstrating the broad ligament and its contents.

(From Drake, Vogl and Mitchell 2005.)

Fig. 77.18 Ovaries and broad ligament, superior view with the uterus lifted away from the bladder.

(From Sobotta 2006.)

Mesosalpinx

The mesosalpinx is attached above to the uterine tube and posteroinferiorly to the mesovarium. Superior and laterally it is attached to the suspensory ligament of the ovary and medially it is attached to the ovarian ligament. The fimbria of the tubal infundibulum projects from its free lateral end. Between the ovary and uterine tube the mesosalpinx contains vascular anastomoses between the uterine and ovarian vessels, the epoophoron, and the paroophoron (Fig. 77.19). The mesovarium projects from the posterior aspect of the broad ligament, of which it is the smaller part. It is attached to the hilum of the ovary and carries vessels and nerves to the ovary.

Mesometrium

The mesometrium is the largest part of the broad ligament, and extends from the pelvic floor to the ovarian ligament and uterine body. The uterine artery passes between its two peritoneal layers typically 1.5 cm lateral to the cervix: it crosses the ureter shortly after its origin from the internal iliac artery and gives off a branch that passes superiorly to the uterine tube, where it anastomoses with the ovarian artery (Fig. 77.19). Between the pyramid formed by the infundibulum of the tube, the upper pole of the ovary, and the lateral pelvic wall, the mesometrium contains the ovarian vessels and nerves lying within the fibrous suspensory ligament of the ovary (infundibulopelvic ligament). This ligament continues laterally over the external iliac vessels as a distinct fold. The mesometrium also encloses the proximal part of the round ligament of the uterus, as well as smooth muscle and loose connective tissue.

Ligaments of the pelvis

Uterosacral, transverse cervical and pubocervical ligaments

The uterosacral ligaments are recto-uterine folds and contain fibrous tissue and smooth muscle (Fig. 77.18). They pass back from the cervix and uterine body on both sides of the rectum, and they are attached to the front of the sacrum. The ligaments can be palpated laterally on rectal examination. On vaginal examination they can be felt as thick bands of tissue passing downwards on both sides of the posterior fornix. The transverse cervical ligaments (cardinal ligaments, ligaments of Mackenrodt) (Fig. 77.20) extend from the side of the cervix and lateral fornix of the vagina to attach extensively on the pelvic wall. At the level of the cervix, some fibres interdigitate with fibres of the uterosacral ligaments. They are continuous with the fibrous tissue around the lower parts of the ureters and pelvic blood vessels. Fibres of the pubocervical ligament pass forward from the anterior aspect of the cervix and upper vagina to diverge around the urethra (Fig. 77.20). These fibres attach to the posterior aspect of the pubic bones.

Fig. 77.20 Supporting ligaments of the pelvis showing the transverse cervical ligaments.

(From Sobotta 2006.)

While the uterosacral and transverse cervical ligaments may act in varying measure as mechanical supports of the uterus, levatores ani and coccygei, the urogenital diaphragm and the perineal body appear at least as important in this respect. There has been renewed interest in the supporting structures of the pelvis, and the subject has been reviewed in detail by Delancey (2000).

Vascular supply and lymphatic drainage

Arteries

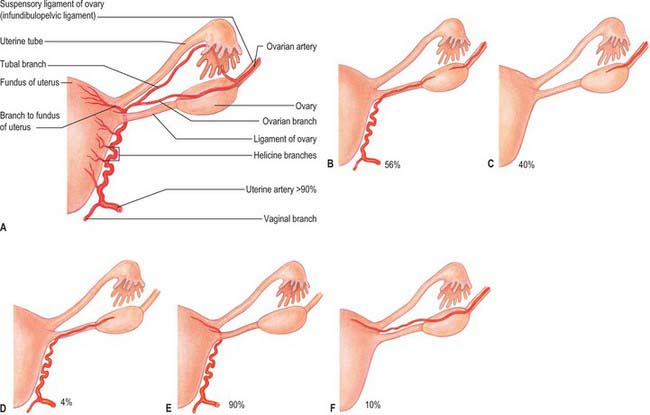

The arterial supply to the uterus comes from the uterine artery (Fig. 77.21). This arises as a branch of the anterior division of the internal iliac artery. From its origin, the uterine artery crosses the ureter anteriorly in the broad ligament before branching as it reaches the uterus at the level of the cervico-uterine junction. One major branch ascends the uterus tortuously within the broad ligament until it reaches the region of the ovarian hilum, where it anastomoses with branches of the ovarian artery. Another branch descends to supply the cervix and anastomoses with branches of the vaginal artery to form two median longitudinal vessels, the azygos arteries of the vagina, which descend anterior and posterior to the vagina. Although there are anastomoses with the ovarian and vaginal arteries, the dominance of the uterine artery is indicated by its marked hypertrophy during pregnancy.

Fig. 77.21 A, Normal arterial supply to uterus, uterine tubes and ovaries. B–F, Variant arterial supply.

(From Sobotta 2006.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree