CHAPTER

6

FEDERAL REGULATION OF PHARMACY PRACTICE

CHAPTER OBJECTIVES

Upon completing this chapter, the reader will be able to:

▶ Understand the provisions and requirements established by the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1990 (OBRA ‘90).

▶ Describe the requirements of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA).

▶ Identify the basic drug- and pharmacy-related provisions of Medicare.

▶ Identify the basic drug- and pharmacy-related provisions of Medicaid.

▶ Recognize the application of the Medicare/Medicaid fraud and abuse laws.

▶ Describe the application of the Sherman Antitrust Act to pharmacy practice.

▶ Describe the application of the Robinson-Patman Act to pharmacy practice.

State governments regulate pharmacists and pharmacies by licensing them. State governments ensure that pharmacists are competent and that pharmacies are appropriately managed to protect the public health. The federal government regulates drug products that are distributed and monitored by state-licensed pharmacists in state-licensed pharmacies. Indirectly, however, the federal regulation of drugs also regulates pharmacists and pharmacies because the drug product is so significantly interwoven into pharmacy practice. The U.S. Congress and federal administrative agencies derive their authority to regulate drug distribution from the Interstate Commerce Clause of the Constitution. The courts have liberally interpreted this clause on several occasions to give Congress considerable power to regulate commerce among the states.

THE OMNIBUS BUDGET RECONCILIATION ACT OF 1990

Federal laws such as the Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act (FDCA) and the Controlled Substances Act (CSA) create for pharmacists an important set of responsibilities related to the integrity of drug distribution to patients. By establishing rules that affect the drug product, these laws indirectly regulate those who handle medications. Yet, until 1990, federal law had not dealt directly with practice standards for pharmacists. The Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1990 (P.L. 101-508, commonly referred to as OBRA ‘90) took a giant leap beyond the rules about drug products set out in the FDCA and the CSA. OBRA ‘90 mandates changes in the way that pharmacy is actually practiced. OBRA ‘90 recognizes a public expectation of pharmacists that goes beyond oversight of drug distribution to include the detection and resolution of problems with drug therapy.

Before the passage of OBRA ‘90, state legislatures, administrative agencies, and courts of law had imposed a variety of requirements on pharmacists. However, none of the efforts that preceded OBRA ‘90 were as comprehensive as this federal legislation. Although the ideas in OBRA ‘90 are not new, the uniform application of them throughout the states marks an unprecedented expansion of pharmacy practice standards. Thus, OBRA ‘90 is perhaps the most important pharmacy-related law of all time, and it merits special attention.

OBRA ‘90 is a massive law that deals with many issues related to government funding. Only a small part of OBRA ‘90 deals with pharmacy practice, but that small part has a profound effect. The establishment of a federal policy requiring drug use review (DUR) to ensure that drug therapy is as safe and effective as possible is a monumental step in the direction of expanded responsibility for pharmacists. Unlike any federal or state legislation that preceded it, OBRA ‘90 places public trust in the pharmacist’s ability to make decisions that improve the quality of drug therapy and increase the likelihood of good outcomes.

The primary goal of OBRA ‘90 is to save money. The U.S. Congress recognized that, as a major payer for health care in the United States, it has the responsibility to ensure that taxpayer dollars are spent properly. Evidently believing that improving the quality of drug therapy could reduce the costs of health care, Congress sought to ensure that patients who need drugs get them, that patients who do not need drugs do not get them, and that patients use drugs as effectively and as safely as possible. Increased quality and reduced cost are by no means mutually exclusive objectives of federal legislation.

OBRA ‘90 was not the first piece of congressional legislation to require that pharmacists review prescribed drug therapy. In 1988, Congress passed the Medicare Catastrophic Coverage Act, which introduced the concept of DUR to improve drug therapy and reduce its costs (P.L. 100-360, 102 Stat. 683 (1988)). The law was repealed in 1989 for economic and financing reasons unrelated to the pharmacist’s DUR, but many of its basic tenets have been incorporated into OBRA ‘90 and expanded. In addition, the Health Care Financing Administration (HCFA), now the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), in 1990 promulgated regulations that expand the pharmacist’s functions in optimizing drug therapy for patients in long-term care facilities (LTCFs).

The U.S. Congress turned to the pharmacy profession for help in solving a national problem. Healthcare costs are excessive, and outcomes of therapy are not as good as they should be. Pharmacy has adopted a “pharmacist care” (originally called “pharmaceutical care”) model of practice in which pharmacists accept responsibility for producing good therapeutic outcomes and improving a patient’s quality of life. In simple terms, OBRA ‘90 has taken the goal that pharmacy developed for itself and has made it a national policy.

The establishment of a national policy regarding pharmacy practice standards requires an indirect approach because only the states, not the federal government, can regulate professional practice. Therefore, the federal government has proclaimed that, as a Condition of Participation in Medicaid, states must establish expanded standards of practice for pharmacists. Technically, this condition does not require that pharmacists take any action; it requires only that states take action. Furthermore, states do not really have to establish the standards, although they cannot continue receiving federal funds for Medicaid if they fail to meet this condition. As a practical matter, of course, this is a professional practice requirement at the federal level because no state can afford not to meet the condition.

Some states have chosen to have the state board of pharmacy promulgate regulations imposing the expanded requirements for pharmacists, whereas other states have left that responsibility to the state Medicaid agency; a few states have established pharmacy practice standards through their legislatures. Depending on the way in which each state acts to fulfill the federal requirement, DUR requirements may appear to apply only to Medicaid prescriptions or they may expressly apply to all prescriptions. Such a distinction is probably meaningless, however. No profession, including pharmacy, has standards of practice that change according to the person being served at the time. The net result of the OBRA ‘90 mandate is that it elevates the standard of care owed by pharmacists to all patients. In addition, OBRA ‘90 provided the minimal requirements that states were required to adopt. Although some states adopted the exact standards as provided in OBRA ‘90, many states opted to adopt stricter standards. Pharmacists must be aware of their state specific requirements that may go above and beyond those listed in OBRA ‘90.

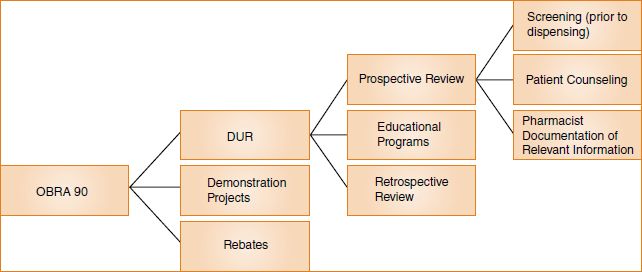

OBRA ‘90 contains a number of significant provisions, but most involve one of three major areas:

1. Rebates

2. Demonstration projects

3. DUR

The parts of the law dealing with rebates and demonstration projects are significant for pharmacy because they can help provide funds for the reimbursement of pharmacists under state Medicaid programs or justify payments to pharmacists for the provision of cognitive services to patients. However, it is the DUR provisions that most directly relate to the everyday practice of pharmacy. (See Figure 6-1).

Rebates

The rebate provision of OBRA ‘90 not only is an important expression of public policy, but also stimulates revenue for state Medicaid programs. Essentially, it requires manufacturers to provide pharmaceuticals to Medicaid at their “best price,” the lowest price at which they sell the product to any customer (42 U.S.C. § 1396r-8(a)). This is accomplished by requiring that the manufacturer pay to each state Medicaid agency the difference between the average manufacturer’s price (AMP) and the “best price.” The AMP is the price that wholesalers pay to the manufacturer for drugs distributed to the retail pharmacy class of trade, after deducting customary prompt pay discounts. For example, if a manufacturer’s best price for a product is $20 per 100 capsules, and the AMP is $30 per 100 capsules, then a rebate of $10 per 100 capsules is owed to Medicaid. The formulas for calculating the amount of the rebate are complex, but the basic concept is quite simple. Medicaid no longer pays top dollar for pharmaceuticals, and other drug purchasers, such as hospitals and health maintenance organizations (HMOs), benefit from preferential prices.

Demonstration Projects

The goal of the demonstration projects funded by OBRA ‘90 is to determine through scientific studies whether the outcomes of patient care improve and the costs decrease when pharmacists are paid to provide DUR services to patients, whether a drug is dispensed or not. The demonstration projects also address the efficiency and cost-effectiveness of online computerized DUR and the cost-effectiveness of face-to-face consultation. If the results of the demonstration projects show that pharmacists can provide cost-effective services, it is highly likely that government agencies and other payers for pharmaceutical services will increase the compensation that they provide for pharmacists.

Drug Use Review

The rebate and the demonstration project provisions of OBRA ‘90 deal primarily with healthcare financing. The DUR provisions, on the other hand, deal primarily with healthcare outcomes. The DUR process has three parts:

1. Retrospective review

2. Educational programs

3. Prospective review

The three functions are all elements of a continuous quality improvement cycle. They are all ongoing, they are necessarily interrelated, and they are of equal importance in DUR.

Retrospective Review

A DUR board that comprises both physicians and pharmacists oversees the retrospective review (42 U.S.C. § 1396r-8(g)(2)(B)). The DUR board performs many activities, but perhaps its most important function is to review data concerning the use of medications over a particular period of time and compare those data with criteria for medication use previously developed by the DUR board. In other words, the DUR board recognizes “ideal” drug therapy and determines whether actual medication use (as evidenced by the data reviewed) conforms to the ideal. During this process, the DUR board will undoubtedly discover that there is room for improvement in the way in which medications are being used. For example, some patients may be receiving duplicative therapy, taking drugs together that have a negative effect on each other, or continuing drug therapy for too long or too short a duration. After identifying areas for improvement, the DUR board may recommend that educational programs be conducted.

Educational Programs

Physicians, pharmacists, or both can be the target of educational programs (42 U.S.C. § 1396r-8(g)(2)(D)). These programs can be face-to-face visits by an expert who calls on a physician or pharmacist; they can be symposia attended by professionals involved with medication use; or they can be written materials delivered to the healthcare professional. The goal of the educational programs is to improve the way that medications are used. This is not unlike the goal of most current continuing education programs for pharmacists and physicians, except that the identification of actual problems through a review of medication-use data prompts the educational programs recommended by the DUR board. These programs should be more effective than current continuing education programs because they address solutions to real problems.

Prospective Review

Through prospective DUR, pharmacists have an opportunity to consider prescribed drug therapy and apply what they know about proper medication use (some of which they have probably learned through educational programs). Prospective DUR generates new data concerning the dispensing of medications, and these data represent the most up-to-date patterns of actual medication use. The DUR board can examine these new data and determine which old problems with drug therapy have been eliminated or diminished and whether new problems have become evident. The DUR process then continues through its three-step cycle. Theoretically, if the DUR board carried out the review cycle enough times, the drug use system could reach a state of perfection, and no additional efforts would be necessary. With new drugs, new patients, new pharmacists, and new physicians entering the system on a regular basis, however, the reality is that DUR will never stop; there will always be room for improvement.

COMPONENTS OF PROSPECTIVE DRUG USE REVIEW

Under OBRA ‘90, prospective DUR requires the active resolution of problems through a comprehensive review of a patient’s prescription order at the point of dispensing. The pharmacist evaluates the appropriateness of medication prescribed for the patient within the context of other information that is known about the patient. Prospective DUR has three components under the OBRA ‘90 mandate:

1. A screen of prescriptions before dispensing

2. Patient counseling by the pharmacist

3. Pharmacist documentation of relevant information

Pharmacists are required to find out necessary information about patients and their medications before dispensing occurs. In addition, pharmacists can empower patients and their caregivers through patient counseling so that patients and their caregivers can improve compliance with therapeutic regimens, avoid medication errors, and ultimately, increase the probability of success of their drug therapy.

Screening Prescriptions

In the screening function that OBRA ‘90 requires, pharmacists must detect “potential” problems. Specifically, OBRA ‘90 states:

The state plan shall provide for a review of drug therapy before each prescription is filled or delivered to an individual receiving benefits under this subchapter, typically at the point-of-sale or point of distribution. The review shall include screening for potential drug therapy problems due to therapeutic duplication, drug-disease contraindications, drug-drug interactions (including serious interactions with nonprescription or over-the-counter drugs), incorrect drug dosage or duration of treatment, drug-allergy interactions and clinical abuse/misuse. (42 U.S.C. § 1396r-8(g)(2)(A)(i))

Particularly noteworthy is the language indicating that the review shall “include” screening. Other activities required to perform prospective DUR go beyond screening. For example, because it makes little sense to conduct a screen of prescribed drug therapy and do nothing with the results of the screen, some action (e.g., notifying the prescriber and requesting clarification, discussing the matter with the patient) should be taken when a problem is detected.

Although computer programs can greatly assist the pharmacist in meeting the screening requirements, OBRA ‘90 is not about computers; it is about professional people and their acceptance of responsibility for the outcome of a patient’s drug therapy. Professional judgment is required to determine whether, for a particular patient at a particular time, there is a possible problem with the way in which a medication has been prescribed.

Counseling Patients

Some potential problems with drug therapy cannot be resolved before dispensing. Even the best screen of potential problems and appropriate action to resolve them cannot remove all of the inherent risks in medication use. Therefore, OBRA ‘90 requires a pharmacist to offer to counsel patients or their caregivers so they can prevent potential problems or can manage problems that arise after the product has been dispensed and the therapy has begun.

Patient Counseling Standards

Pharmacists must “offer to discuss” with each patient or caregiver matters that in the pharmacist’s professional judgment are significant, including

• The name and description of the medication

• The dosage form, dosage, route of administration, and duration of drug therapy

• Special directions and precautions for preparation, administration, and use by the patient

• Common severe side effects, adverse effects, or interactions and therapeutic contraindications that may be encountered, including ways to prevent them and the action required if they do occur

• Techniques for self-monitoring drug therapy

• Proper storage

• Prescription refill information

• Action to be taken in the event of a missed dose (42 U.S.C. § 1396r-8(g) (2)(A) (ii)(I))

The deference to professional judgment in the patient counseling requirement means that pharmacists should rely on their training and experience to determine what information is relevant for a particular patient. The goal of OBRA ‘90 is not for all patients to receive the same information about a drug, but for each patient to receive the information about a drug that is particularly relevant to that patient’s circumstances. Furthermore, “professional judgment” does not mean business judgment. Deciding not to counsel a patient or to reduce the length of a counseling session because it is inconvenient or difficult for the pharmacist is not consistent with the purpose of OBRA ‘90. A pharmacist should withhold information from a patient only when it is in the patient’s best interest not to receive the information, not when it is in the pharmacist’s best interest to withhold the information.

The phrase “common severe side effect” can be interpreted in various ways. It could be argued that only for extremely serious illnesses does the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approve drugs with side effects that are both common and severe. Congress probably did not intend that patients be counseled only under those rare circumstances, however. Rather, the intent of Congress appears to be that pharmacists discuss with patients those side effects that are common (of high probability) or severe (of high magnitude), as well as those that are both common and severe. As a result, standards may vary in different states. For example, some states require patient counseling for new prescriptions only, whereas others require counseling for refills as well.

Even a superficial reading of the OBRA ‘90 legislation discloses that there really is no explicit patient counseling requirement. Instead, the legislation requires the pharmacist make an offer to discuss medications with patients. Some states have permitted a nonpharmacist to make this offer, whereas others require that the pharmacist make the offer personally. Pharmacists must do the actual counseling; however, in most states interns may be able to assist under the direct supervision of the pharmacist. If it is not practicable to counsel in person, such as a mail-order prescription, the pharmacy must provide access for counseling by means of a toll-free telephone number.

Waiver of Counseling

The pharmacist’s duty to counsel under OBRA ‘90 and under the rules implemented by states pursuant to the mandate of OBRA ‘90 is for the benefit of patients. If patients prefer not to be counseled, then they have a right to refuse counseling. Specifically, OBRA ‘90 states:

Nothing in this clause shall be construed as requiring a pharmacist to provide consultation when an individual receiving benefits under this subchapter or caregiver of such individual refuses such consultation. (42 U.S.C. § 1396r-8(g)(2)(A)(ii)(II))

Although patients can waive the right to be counseled about drug therapy, the law contemplates an informed right. If a clerk or other personnel asks, “You don’t want to wait 45 minutes to be counseled by the pharmacist, do you?” and the patient or caregiver answers, “No,” this is not the type of informed refusal that Congress anticipated. Even asking the question in a completely neutral and uninviting tone (e.g., “Do you want to be counseled?”) can lead to a refusal by a patient who would really like to be counseled if the patient understood what was being offered. A refusal can be considered effective only if the patient truly understood the offer and really did not want the counseling. A patient who refuses counseling because the pharmacist or someone else in the pharmacy made it clear that the pharmacist really does not want to be bothered with counseling has not received the benefit of the services that OBRA ‘90 intends.

Just as some pharmacists now ask patients who refuse child safety closures on prescription containers to put their refusal in writing, it may be prudent for a pharmacist to obtain a written waiver of the right to be counseled. It is much more important that the waiver be informed and voluntary, however, than that the waiver be put in writing. If a pharmacist has maintained a logbook or other written record in which most notations show refusals to be counseled, the pharmacist has made a record of his or her own lack of compliance with the OBRA ‘90 mandate. The waiver of the right to be counseled should be the exception to the rule. Those pharmacists who permit the exception to become the rule will discover that they have created legal difficulties for themselves.

Documenting Information

OBRA ‘90 requires pharmacists to maintain a written record that contains information about patients and the pharmacists’ impressions of the patients’ drug therapy. OBRA ‘90 provides:

A reasonable effort must be made by the pharmacist to obtain, record, and maintain at least the following information regarding individuals receiving benefits under this subchapter:

(aa) Name, address, telephone number, date of birth (or age), and gender.

(bb) Individual history where significant, including disease state or states, known allergies and drug reactions, and a comprehensive list of medications and relevant devices.

(cc) Pharmacist comments relevant to the individual’s drug therapy. (42 U.S.C. § 1396r-8(g)(2)(A)(ii)(II))

The “reasonable effort” that pharmacists must make to record information about patients, including their comments relevant to a patient’s drug therapy, would be deemed reasonable only if an impartial observer can review the documentation in a pharmacy and understand what has occurred in the past. It should be possible to tell from the documentation what a pharmacist discovered about a patient, what the pharmacist told the patient, and what the pharmacist thought about the patient’s drug therapy at the time of dispensing. The documentation should:

• Serve as a reminder to the pharmacist (because nobody’s memory is perfect)

• Provide a reference for other pharmacists in the same pharmacy

• Contain information for surveyors who need to record what was done and connect that action with an outcome if possible

• Show enforcement officials that the OBRA ‘90 requirements are being met

• OBRA ‘90 recognizes a public expectation of pharmacists that goes beyond oversight of drug distribution to include the detection and resolution of problems with drug therapy.

• States were required to adopt the minimal standards under OBRA ‘90 to continue to participate in Medicaid; however some states may have stricter requirements.

• The basic framework of OBRA ‘90 includes rebates, demonstration projects, and DUR.

• The DUR process includes retrospective review, educational programs, and prospective review.

• The components of the prospective review are screening of prescriptions prior to dispensing, the offer of patient counseling, and documentation of patient information.

Jack is the V.P. for Pharmacy Services for a drugstore chain whose pharmacies are extremely busy. Some of the chain pharmacies and pharmacists have been fined for not counseling and not following other OBRA ‘90 requirements. As a result, Jack sent out instructions to all pharmacies that for every new prescription, a clerk or technician must ask the patient if he or she would like counseling. If the patient does want counseling, the clerk must tell the patient that because the pharmacists are very busy, it could be a 10- to 15-minute wait. If the patient then declines counseling, the clerk must have the patient sign a waiver of counseling. Clerks are instructed to give information forms to patients to be completed, asking for demographic characteristics and significant medical and drug information.

1. In what ways has Jack complied with the requirements of OBRA ‘90? In what ways has Jack failed to comply with the requirements of OBRA ‘90?

2. If you were an employee of one of Jack’s pharmacies, what further changes would you recommend to bring Jack’s pharmacies into compliance with the language and intent of OBRA ‘90?

HEALTH INSURANCE PORTABILITY AND ACCOUNTABILITY ACT OF 1996

Congress’s enactment of HIPAA in 1996 significantly affected pharmacy practice and the entire healthcare system (P.L. No. 104-191, 110 Stat. 1936 (1996)). HIPAA is a sweeping, complex law with the overall goal of improving the efficiency and effectiveness of the healthcare system. Among other things, the law seeks to improve the portability and continuity of health insurance coverage and to prohibit discrimination in health coverage. Of greatest interest to pharmacists, HIPAA also regulates the privacy and security of health information, and authorizes the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) to enact regulations to this effect. Public concern over the use, efficiency, security, and abuse of electronic records provided the catalyst for the development of patient health information requirements.

HIPAA targets four aspects of health information: (1) transaction and code sets, (2) national provider identities, (3) security, and (4) privacy. DHHS has enacted final regulations for all four of these areas. In February 2003, the agency enacted final regulations addressing electronic data transaction and code sets (68 Fed. Reg. 8381). These regulations provide for uniform standards in the electronic transmission of claims and data with the intent of improving efficiency and lowering costs. DHHS established final regulations for national provider identities in January 2004 (69 Fed. Reg. 3434). The regulations took effect May 23, 2005, at which time healthcare providers could begin applying for a national provider identifier (NPI) number. All healthcare providers covered by HIPAA had to receive and use the NPI by the compliance date of May 23, 2007. Prior to the NPI requirement, a provider may have had a different identification number for each plan in which the provider participated. The intent of requiring a single NPI for each provider is uniformity, administrative simplicity, and cost.

The final security regulations, enacted in February 2003, sought to protect the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of electronic health information (68 Fed. Reg. 8334). They established requirements that covered entities (those entities to whom the regulations apply) must implement to protect the information from unauthorized access, alteration, deletion, and transmission. Physical, technical, and organizational procedure safeguards must be established. Entities are free to develop their own security measures by written policies and procedures, as long as they achieve the objectives and standards contained in the regulations.

In contrast to the security requirements, the privacy regulation standards are concerned with the patient’s rights and how and when the patient’s information may be used (67 Fed. Reg. 53182). The privacy regulations, which took effect April 14, 2003, generally represent the greatest concern to practicing pharmacists and their staff, and are the subject of most of the remainder of the HIPAA discussion. The intent of the HIPAA privacy discussion in this chapter is to provide a general overview. Readers requiring more information are urged to go to the DHHS and Office for Civil Rights (OCR) websites, where they can access guidance documents and answers to frequently asked questions (FAQs). (See http://www.hhs.gov/ocr/privacy.)

In January 2013, DHHS issued another final rule which became effective March 26, 2013 (78 Fed. 5566; hereinafter “2013 rule”). The 2013 rule included modifications to the original HIPAA rules as well as additional HIPAA related laws. In addition, the 2013 rule strengthened the privacy and security protections for health information, as well as enforcement of HIPAA. The 2013 rule can be accessed at http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2013-01-25/pdf/2013-01073.pdf.

Prior to HIPAA, numerous abuses of patient health information were reported. For example:

• A chain pharmacy sold its used computers to the public complete with patient prescription and patient profile databases still intact.

• A retiring physician sold his patients’ medical records to a business, which then resold the records back to the patients.

• The 13-year-old daughter of a hospital employee obtained a list of hospital patients’ names and phone numbers from the hospital and as a joke called patients and told them they had human immunodeficiency virus.

• Drug manufacturers commonly obtained from pharmacies lists of patients taking certain prescription medications and then would send those patients letters urging them to ask their physician to change them to another medication.

• Laboratories commonly sold patient lab results to drug companies, which would then use the information to target patients to promote their medication.

• Employers would access individuals’ medical information and use it to determine whether to hire or fire employees.

These represent only a few examples of patient privacy abuse. Prior to HIPAA, no federal regulation of the privacy of patient health information existed. Moreover, state laws in many instances were inadequate to protect patients against these abuses. HIPAA requirements establish national uniformity and preempt state laws that are less strict.

Called “covered entities” under the privacy rule, health plans, healthcare clearinghouses, and healthcare providers that conduct financial or administrative transactions electronically must comply. The regulations ordinarily apply to the entire covered entity; however, a company may exempt certain non–healthcare parts of its operation, such as a grocery store that contains a pharmacy. In addition, with the 2013 rule modifications to HIPAA, business associates of covered entities are also directly liable for compliance with certain of the HIPAA privacy and security requirements.

Information covered under HIPAA is called protected health information (PHI). Originally the government intended to include only electronic information, but ultimately extended the definition of PHI to include all forms of health information that (1) relate to past, present, or future physical or mental health; the provision of care; or payment for care; and (2) identify the patient or could reasonably be expected to identify the patient.

Obviously, in a pharmacy this would include any prescription or other health information, including payment records for tax purposes or otherwise.

A pharmacy must provide a “Notice of Privacy Practices” to each patient containing several items of information including

• How the pharmacy intends to use and disclose the information

• The pharmacy’s obligation to notify the patient of a breach of unsecured PHI

• A statement that the individual can restrict certain disclosures of PHI to a health plan when the individual pays for the treatment out of pocket in full

• Descriptions of the legal duties of the pharmacy to protect the confidentiality of PHI

• A statement regarding uses and disclosures that require authorization

• A statement of the patient’s rights and a brief explanation of how the patient may exercise those rights

• A statement that patients may complain to the pharmacy or DHHS and that explains the method for filing a complaint

• A person in the company whom a patient may contact with privacy concerns, including the person’s name or title and telephone number

The notice must be provided in paper form on the day the pharmacy first provides service, unless the patient consents to electronic transmission. The notice must also be posted in a prominent and visible location and made available on request to any person, whether the person is a patient or not. If the pharmacy has a website, the notice must be posted on the site.

A pharmacy must make a good-faith effort to distribute the notice to patients and obtain a written acknowledgment of receipt. Only one signed acknowledgment is required for each patient, meaning an acknowledgment is not required every time a prescription is dispensed. A pharmacy may not refuse treatment to a patient who refuses to sign the acknowledgment. The written acknowledgment can occur by several means, including having the patient sign or initial a tear-off form on the notice or by having the patient sign a logbook.

If the patient does not personally pick up the prescription, the pharmacy could mail the notice to the patient with an acknowledgment form that the patient could sign and return. Alternately, the pharmacy could attempt to obtain the acknowledgment electronically. If the patient does not return the acknowledgment, the pharmacist should attempt again. Failure to receive an acknowledgment is not a violation, because the pharmacy need only make a good-faith effort; however, the effort should be documented. The patient’s personal representative (someone authorized by state law to act for a patient, such as the parent of a minor child, a legal guardian, or someone with a power of attorney) may sign the acknowledgment for the patient. Although friends and relatives may pick up a prescription for a patient as an agent of the patient, they may not sign the acknowledgment unless they are also a personal representative of the patient.

The privacy rule allows pharmacies to use and disclose PHI for treatment, payment, and operations (TPO). Treatment includes providing, coordinating, or managing the health care of the patient. In pharmacies, this includes dispensing medications, counseling patients, maintaining patient profiles, and consulting with the patient’s other healthcare providers. Importantly, the pharmacist may disclose PHI with the patient’s primary care physician or nurse practitioner, as well as any other healthcare professionals involved in treating the patient. Payment activities include submitting claims for reimbursement, determining patient eligibility and extent of coverage, and sending bills to patients. Operations encompass those activities necessary to operate a pharmacy such as quality assessment, fraud detection, audits, certifications, and business management.

Pharmacists, of course, may always provide complete disclosure of PHI to the patient, and in fact the regulations require the pharmacist to do so if the patient requests. Pharmacies may charge a reasonable, cost-based fee for providing patients a copy of their records. Disclosure may also be made to the patient’s personal representative, or agent, such as a friend, relative, roommate, or neighbor. In the case of an agent, the pharmacist should exercise professional judgment to determine if it would really be in the patient’s best interests to provide disclosure. This puts the pharmacist in somewhat of a dilemma, especially in mandatory consultation states such as California, because state regulation requires the pharmacist to counsel the patient or the patient’s agent if present. Regardless of the counseling requirements, it would be best not to counsel the patient’s agent unless professional judgment clearly warrants, and instead, send a notice for the patient to call for counseling.

Under HIPAA, patients have always had the right to request covered entities to access and obtain copies of their PHI in a timely manner. Prior to the 2013 rule, covered entities had 60 days to act on requests for PHI, with an additional 30-day extension. The 2013 rule, however, has modified that requirement to 30 days, and if there is good cause, it may be extended another 30 days by providing the patient with a written explanation for the delay. DHHS encourages patient access as soon as possible, and for pharmacies, PHI information may be instantaneously available and time constraints may not be a concern. However, for covered entities that continue to make use of off-site storage or have additional time constraints to providing access, the 30-day window, with the potential for a 30-day extension, can be exercised.

Pharmacies are also required to provide an electronic copy of PHI to patients in the format requested. If the request can’t be accommodated, then it must be provided in an agreed-upon readable electronic format.

Accounting for Disclosures

Under the initial HIPAA law and regulations, patients had a right to request and receive an accounting of disclosures of PHI made by a covered entity in the six years prior to the date of the request. That right did not extend to disclosure for TPO because covered entities commonly make these disclosures several times per day and tracking them would be unduly burdensome. However, a 2009 law called the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH), which is part of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (P.L. 111-5), made an important change. Under HITECH, if a covered entity utilizes an electronic health record, the entity will be required to account for all disclosures, including disclosures of TPO, within three years prior to the date of the request. Pharmacy organizations are very concerned that this new HITECH requirement will unduly burden pharmacies, because pharmacies make several disclosures daily when claims processing is considered, and have requested to DHHS that exceptions be made for pharmacy. Because of these concerns, DHHS is not expected to finalize rules for accounting for disclosures until 2015.

HITECH contains another disclosure-related requirement problem for pharmacies. Patients may request that their PHI not be disclosed to a health plan if the purpose is for payment or operations and pertains to an item or service for which the patient has paid out of pocket in full. Pharmacy claims submitted to health plans, however, include PHI related to TPO, and it might be very difficult to extract this information. Not including all this information might also violate the contract between the pharmacy and the health plan. This requirement was finalized in the 2013 rule, and it is important that pharmacies understand that if a patient pays for a prescription or other goods or services with cash, the patient can prevent the pharmacy from disclosing information about treatment to his or her health insurers.

Minimum Necessary Requirement

A pharmacy may disclose only the minimum amount of PHI necessary to accomplish the objective. For example, if a claims processor needs more information in order to process a claim, the pharmacy may provide only that information and no more. Exceptions to the “minimum necessary requirement” include

• Communications to the patient

• Communications regarding the treatment of the patient with other providers involved in the treatment

• When authorized by the patient

• When required by DHHS for compliance and enforcement purposes

• When required by law

In all of these situations, the pharmacist may provide complete disclosure of PHI. Prior to HITECH, HIPAA contained no definition of minimum necessary. HITECH changed this and limits the covered entities’ discretion for determining what constitutes minimum necessary to, if possible, a “limited data set.” A limited data set is PHI that excludes direct identifiers of the patient, such as name, address, phone numbers, and social security number. If restricting the PHI to a limited data set is not possible, the pharmacy may include direct identifiers to the minimum amount necessary to achieve the intended purpose. The pharmacy must be prepared, however, to justify why the request or disclosure was not limited to the limited data set.

Incidental Use and Disclosure

It is virtually inevitable that no matter how careful a pharmacy is about protecting PHI, the information will inadvertently be used or disclosed in an unintended manner. For example, while counseling a patient, another patient may overhear the conversation. Pharmacies are not liable for these incidental uses and disclosures provided they have applied “reasonable safeguards” to protect the PHI. Pharmacies are not expected to make structural modifications, such as building a soundproof room for counseling. Pharmacists, however, are expected to exercise professional judgment and common sense. Reasonable safeguards for counseling would indicate that the counseling be conducted in a location as far away from other patients as possible. If other patients are nearby, they should be asked to stand back a few feet and the pharmacist should speak softly while counseling.

The OCR has specifically stated that under the incidental use and disclosure policy, no violation occurs when the pharmacy calls out the name of the patient who is waiting for a prescription, nor would it be a violation if another patient incidentally hears the pharmacist speaking to a technician or another pharmacist about a prescription. Pharmacists may also leave messages on the patient’s answering machine, although it would be wise to say as little as possible.

De-identification of PHI

Information from which all individual identifying factors have been removed, termed de-identification, is not PHI and thus not subject to HIPAA. Pharmacists and pharmacy students, when using patient information for educational and other non-TPO purposes, should take care to de-identify the information. The following items are considered identifiable:

• Names

• Geographic subdivisions such as street address, city, county, and zip code

• All dates: birth, admission, discharge, death, ages over 89 (may aggregate to category, e.g., age 90 and over)

• Telephone numbers

• Fax numbers

• Electronic mail addresses

• Social Security numbers

• Medical record numbers

• Health plan beneficiary numbers

• Account numbers

• Certificate/license numbers

• Vehicle identifiers and serial numbers, license plate numbers

• Device identifiers and serial numbers

• Web universal resource locators

• Internet protocol address numbers

• Biometric identifiers (finger and voice prints)

• Full-face photographic images and comparable images

• Any other unique identifying numbers, characteristics, or codes

Considerations for Pharmacy Students in Early and Advanced Experiences

Pharmacy students often monitor assigned patients and give case presentations. Unless the patient gives specific authorization, all patient identification information should be removed. In institutional settings, pharmacy students should refrain from discussing patients in public places such as on elevators, in hallways, and in the cafeteria. Patient charts or other PHI should not be left where others can read them; this includes computer screens. If a computer is shared with others, protect files containing PHI from access. In community settings, apply essentially the same rules. In addition, do not discuss a patient’s medications with pharmacy staff such that other patients can overhear, and do not counsel patients in store aisles about over-the-counter (OTC) drugs when other people can overhear.

Other Permissible Use and Disclosure of PHI

As discussed, a pharmacy may not use or disclose PHI except for TPO purposes, or to the patient or the patient’s personal representative or agent. In addition, the privacy regulations allow the pharmacy to disclose PHI for governmental-type reasons, including

• Public health activities (e.g., to authorized health officers)

• Judicial and administrative proceedings (requests should be made pursuant to a court or administrative order, or subpoena)

• Law enforcement purposes (e.g., to law enforcement officers in certain circumstances)

• Serious threats to health or safety (e.g., in suspected cases of abuse, neglect, or endangerment)

• As required by law

In these and related situations, the pharmacist should always contact the privacy officer and an attorney before releasing information.

Breach of PHI

The original HIPAA privacy laws and regulations failed to address the issue of breaches of PHI. HITECH did and requires DHHS to issue interim final regulations requiring covered entities to provide notification when unsecured PHI is breached. DHHS complied by issuing interim final breach notification regulations in August of 2009 (74 Fed. Reg. 42740). Thereafter, the 2013 rule provided for modifications to the interim final regulations regarding breach notification under HITECH.

The regulations apply to HIPAA-covered entities, including pharmacies, and their business associates. Importantly, the law and regulations apply only to unsecured PHI, defined as PHI that is not rendered unusable, unreadable, or indecipherable to unauthorized persons through the use of a technology or methodology as approved by DHHS. All unsecured PHI in all forms, including electronic, paper, or oral, are subject to the regulations. Pharmacies must confirm with their intellectual technology vendor whether the pharmacy’s PHI is secured or not.

A breach is defined as “the acquisition, access, use, or disclosure” of PHI in an unpermitted manner that “compromises the security or privacy of the PHI”; meaning that it poses a significant risk of financial, reputational, or other harm to the individual. The regulations provide exceptions including (1) when the acquisition, access, use or disclosure is unintentional and in good faith and does not result in further use or disclosure, (2) when the unauthorized person to whom the PHI has been disclosed would not reasonably have been able to retain it, and (3) when the disclosure is inadvertent between two authorized individuals at the same facility if the information is not further used or disclosed.

For pharmacies, unless an exception applies, an unpermitted use or disclosure of PHI is presumed to be a breach unless the pharmacy can demonstrate that there is a low probability that the PHI has been compromised. In determining this, the pharmacy would conduct a risk assessment using specific factors, including: the nature and extent of the PHI involved, the unauthorized person who used the PHI or to whom the disclosure was made, whether the PHI was actually acquired or viewed, and the extent to which the risk to the PHI has been mitigated. If a breach has occurred, the pharmacy must notify the affected individual(s) by first-class mail (or electronically if the individual has agreed) within 60 days after the breach was discovered. The regulation contains the elements that must be included in the notification. In addition, the pharmacy may have to notify DHHS of breaches depending on the number of individuals affected. As an example: Assume that a pharmacy employee places patient A’s medication in a bag for patient B and places patient B’s medication in a bag for patient A. Patient A is given the bag and starts to walk away from the pharmacy when the error is discovered. If the pharmacy personnel can determine that patient A could not have read or retained the information, then this situation would most likely not be a breach pursuant to the exception. If, however, patients A and B were each given the wrong bags and each patient later discovered the error and returned the medications, most likely this should be considered a breach. Notification would be required to patients A and B. If the pharmacy does not have sufficient contact information for either patient, the regulation allows for substitute notice. The regulations specify what constitutes substitute notice depending upon whether less than 10 or more than 10 individuals are affected. If more than 500 individuals are affected, the pharmacy must also notify the media within 60 days after discovery and must notify DHHS immediately.

Disposal of PHI

Because of incidents involving improper disposal of PHI, such as CVS pharmacy disposing of PHI in dumpsters, which resulted in a $2.5 million fine, OCR posted FAQs about the disposal of PHI in February 2009 (http://www.hhs.gov/ocr/privacy/hipaa/enforcement). The document emphasizes that covered entities must implement reasonable safeguards to protect PHI that is disposed, including the training of workforce members who dispose of PHI. Although the regulations do not require a particular disposal method, simply abandoning PHI or disposing of it in dumpsters accessible to the public without rendering the PHI unreadable and unable to be reconstructed is definitely not permitted. Covered entities must develop and implement reasonable policies and procedures for disposal. Examples provided in the FAQ include shredding or burning paper records; placing labeled prescription containers in opaque bags in a secure area to be picked up by a disposal vendor; and clearing, purging, or destroying electronic media. Although it is preferable to hire a business associate to ultimately dispose of PHI, it is not required.

Marketing, Sale of PHI, and Patient Authorizations

HIPAA provides individuals with controls over how their PHI can be sold or used and disclosed for marketing purposes. In general, HIPAA requires an individual’s written authorization before his or her PHI can be sold or used for marketing. Authorizations must be detailed and customized for the particular use or disclosure intended, contain an expiration date, and be signed by the patient. A patient may not be denied treatment for refusing to sign an authorization.

Marketing means to make a communication to an individual about a product or service that encourages the individual to purchase or use that product or service. DHHS provides exceptions to what is considered marketing and therefore not requiring individual authorization, in order to help ensure essential healthcare communications are not impeded. Exceptions to marketing include communications about general health issues, as well as communications made

• For the treatment of the individual

• Face to face

• For case management or care coordination

• To direct or recommend alternative treatment, therapies, healthcare providers, or settings of care

• About the health-related services offered by the pharmacy or a health plan

For example, if a pharmacy wanted to mail patients a communication about a non–health-related product or service, individual authorization would be required.

The 2013 rule modified existing rules regarding marketing and now requires that if there is financial remuneration related to the communication, then even treatment-related communications constitute marketing. For example, if a pharmacy wanted to send their diabetic patients a brochure about a new diabetes mobile application offered by a third-party software developer, and the pharmacy was paid by the software developer for the costs of the brochure, time for organizing the mailing, and an additional financial incentive, this would be considered marketing, and individual authorization would have to be obtained prior to sending out the brochures. Alternatively, if the same pharmacy communicated information about the mobile application face to face with patients while they were visiting the pharmacy, individual authorization would not be required.

DHHS has expressly provided one important marketing exception: for refill reminders and other communications about a drug or biologic currently being prescribed to the individual (known as the “refill reminder” exception). This exception applies if any financial remuneration received by the pharmacy in exchange for making the communication is reasonably related to the pharmacy’s cost of making the communication (i.e., costs of drafting, printing, and mailing). However, specifically for the “refill reminder” exception, if a pharmacy receives a financial incentive from a drug company beyond the cost of providing the refill reminders, individual authorization would then be required, unless the communication was during a face-to-face encounter. DHHS has also stated that communications regarding the generic equivalent of a drug being prescribed to an individual as well as adherence communications encouraging individuals to take their prescribed medication as directed fall within the scope of the “refill reminder” exception.

The 2013 rule also distinguishes between marketing of PHI and PHI for sale. Sale of PHI occurs when a covered entity discloses PHI for remuneration, as opposed to encouraging an individual to purchase or use a product or service. In general, a pharmacy would not be permitted to exchange PHI for direct or indirect remuneration without obtaining prior authorization.

Pharmacies do business with outside entities in which the sharing of PHI is necessary. A few examples include businesses that engage in claims processing, data processing, software developing, quality assurance analysis, billing services, and refill reminder services. The regulations term these outside businesses as business associates. The pharmacy must have a business associate contract with the entity in order to share PHI, and all PHI is subject to the minimum necessary requirement. Prior to HITECH, the privacy and security responsibilities of a business associate were defined by the contract with the covered entity. Thus, if the business associate violated any privacy and security requirements, it was liable to the covered entity under breach of contract. Under HITECH, business associates are now directly responsible and accountable to maintain and protect PHI in the same manner as covered entities and are subject to HIPAA enforcement authority.

All pharmacies must train all members of its pharmacy department workforce about its HIPAA policies and procedures within a reasonable time after being hired. The pharmacy must provide additional training if it makes a material change in its policies and procedures. DHHS estimates that workers should receive on average one hour of training. The pharmacy must document that each worker has completed training. The training requirement creates a hardship for pharmacy students in early experiential and clerkship programs. They will have to complete a training program for each covered entity where they work. Moreover, the pharmacy school itself should provide a training program that each student should complete. As if this were not enough, the students must also complete training programs at the pharmacies where they intern.

Pharmacies must develop policies and procedures to implement the HIPAA privacy standards. This includes identifying a privacy officer to oversee the pharmacy’s privacy compliance program and enumerating the privacy officer’s responsibilities. The policies and procedures must provide for the imposition of sanctions against any worker who violates the privacy rules or the pharmacy’s policies and procedures.

Penalties for violating HIPAA can be severe and were made even more so under the 2009 HITECH law. Unintentional violations can result in fines of $100 per violation, up to $25,000 per person for all violations in a calendar year. Violations due to reasonable cause and not willful neglect can result in fines of $1,000 per occurrence, but not more than $50,000 for all violations in a calendar year. Willful neglect violations that are corrected within 30 days can result in fines of $10,000 with an annual cap of $250,000. Fines for willful neglect violations not corrected within 30 days can be up to $50,000 per violation with an annual cap of $1,500,000. Violations that are intentional or that involve fraud are subject to more severe penalties including prison. HITECH now allows state attorneys general in addition to DHHS (via OCR) to bring civil actions in federal court to enforce HIPAA.

Regarding enforcement of HIPAA, the 2013 rule provides for an increase in DHHS authority to investigate and sanction noncompliant entities. Therefore, there may be an increase in enforcement actions under HIPAA in the future. DHHS provides case examples and resolution agreements to help show how covered entities can comply with HIPAA requirements. (See http://www.hhs.gov/ocr/privacy/hipaa/enforcement/examples/index.html.)

Although HIPAA provides for civil and criminal penalties against pharmacies when there is a violation, it does not create a private cause of action for individuals to sue. However, pharmacists should be aware that improper disclosure of PHI could be used in state court actions, including negligence and invasion of privacy lawsuits. In Hinchy v. Walgreen Co., et al., No. 49D06 11 08 CT029165 (Marion Co. Sup. Ct., Ind., filed August, 1, 2011), a patient sued Walgreens in state court, alleging negligence when a pharmacist intentionally breached their PHI and shared it with a third party. The court used HIPAA for the standard of care in patient privacy, and the jury awarded the patient 1.4 million dollars against the pharmacy.

HEALTH INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY INFRASTRUCTURE

Health information technology (HIT) is generally considered the critical element in improving the quality and efficiency of the nation’s healthcare system. Although adoption of electronic record systems has increased at larger healthcare facilities, many healthcare professionals and facilities have yet to convert. Cost appears to be the most significant barrier. HITECH, in addition to strengthening the privacy and security requirements of HIPAA, appropriates almost $20 billion to develop a nationwide HIT infrastructure. The objectives of establishing the HIT infrastructure are to protect the privacy of PHI, reduce medical errors, reduce costs by improving administrative efficiency, improve coordination among healthcare providers, and improve the provision of public health services and emergency response systems. Prescribers and hospitals (not pharmacies) will receive financial incentives to adopt electronic medical record technology.

The law expands and adds funding to the Office of the National Coordinator for HIT (ONCHIT), which oversees the HIT infrastructure. ONCHIT, within DHHS, is responsible for developing HIT standards and regulations in conjunction with DHHS and two appointed committees, the HIT Policy Committee and the HIT Standards Committee. ONCHIT and DHHS are also responsible for developing and regulating national and regional HIT research centers and for providing grant funding to educational institutions (including pharmacy schools) to incorporate HIT into clinical education and to develop medical informatics education programs.

• HIPAA regulates four aspects of health information: (1) transaction and code sets, (2) national provider identities, (3) security, and (4) privacy.

• Covered entities, such as pharmacies, as well as business associates, must comply with HIPAA.

• PHI is protected by HIPAA. De-identified information is not PHI.

• Pharmacies must make a good-faith effort to distribute and obtain a written acknowledgment of receipt of their “Notice of Privacy Practices.”

• PHI can be used and disclosed for TPO; however, pharmacies are only permitted to disclose the minimum amount of PHI necessary to accomplish the objective.

• Patients have a right to request an accounting and disclosure of PHI.

• Under HITECH, pharmacies are required to address breaches of PHI.

• Sale of PHI and use of PHI for marketing, with limited exceptions, requires individual authorization.

• Penalties for HIPAA can be severe and could be the basis for lawsuits in state court.

TAKE-AWAY POINTS

TAKE-AWAY POINTS STUDY SCENARIO AND QUESTIONS

STUDY SCENARIO AND QUESTIONS TAKE-AWAY POINTS

TAKE-AWAY POINTS