Put an idea into your intelligence, and leave it there an hour, a day, a year without ever having occasion to refer to it. When at last you return to it, you do not find it as it was when acquired. It has domiciled itself, so to speak, become at home, entered into relations with your other thoughts, and integrated itself with the whole fabric of the mind.

–John Livingston Lowes. From The Road to Xanadu.

CONDUCTING A FEASIBILITY EVALUATION FOR A COMPLEX OR LARGE MULTINATIONAL CLINICAL TRIAL

Prior to committing a company’s resources and efforts to initiating a highly complex or large clinical trial, particularly one that will be conducted in several or many countries, it is often wise to conduct a feasibility evaluation. This would be done by representatives of the sponsor (e.g., Clinical Research Associates or quality assurance staff) or a vendor that visits potential sites with a short questionnaire and interviews the proposed investigator. The vendor chosen could be an organization that sends people out from a central site to each of the countries that is being considered for inclusion in the trial or an organization that has offices in all, or at least most, of the countries being considered for the trial.

Objectives of Conducting a Feasibility Study

Some of the main reasons to conduct a feasibility study are to:

Determine which country or countries are most appropriate to conduct the trial

Identify potential investigators who have the interest, patients, staff, time, and facilities to conduct the trial; the number of other ongoing and planned trials that would compete for patients will also be obtained

Ascertain the reactions of the potential investigators to the penultimate draft of the clinical protocol and any suggestions they have for modifications

Learn the costs of several aspects of conducting the trial including investigator fees, travel fees, local hotel and per diem pass through costs, and other financial costs

Learn about regulatory and legal requirements, practices, and any issues in each region or country, including the details of importing drug and exporting biological samples

Determine how data can be efficiently transmitted to the sponsor, contract research organization (

CRO), or data management organization

Estimate the rate of patient recruitment and enrollment and any specific issues relating to recruitment or patient retention

Based on the previous data, it should be possible to estimate the time for study initiation, duration of recruitment, time to conduct of the trial, and the number of study sites to be enlisted.

Steps in a Feasibility Study

After the protocol is in an advanced stage and it is 95% certain that the main elements will not be modified and a vendor is chosen (or some are being interviewed) to conduct interviews at possible study sites in each of the countries, it is necessary to plan the visit to the sites.

Confidentiality Disclosure Agreements

A confidentiality disclosure agreement (

CDA; sometimes called a nondisclosure agreement or secrecy agreement) must be signed by each investigator to be visited prior to visiting the site. This assumes that they will be given the protocol, the investigator’s brochure, and/or other documents that are confidential about the drug or study. The sponsor or vendor should try to make the

CDA easy for the site to understand and agree to, as many

CDAs currently take a great deal of time for an institution to review and to sign.

CDAs are commonly signed by a person or group who receives information or a representative of their institution. The document guarantees that the data or information received will be kept in strict confidence for a fixed period of time, often from two to ten years. Many conditions of this agreement are detailed, and these agreements often range from two to six pages (single-spaced) in length. In some cases, these agreements are bilateral and provide for mutual confidentiality of shared information from each of the parties. Confidentiality clauses and details serving the same purpose are often also included in contracts for services provided by one entity to another.

What the Sponsor or Vendor Should Check during the Site Visit

During the visit to each site, it is relevant to identify the items listed in

Table 68.1.

A polished protocol should be shown to each of the sites prior to the visit, but only after the

CDA is signed. The protocol should be virtually complete, because if the protocol is subject to major changes after the visit to the sites, the entire feasibility exercise would lose its value and, theoretically, would have to be repeated. Prepare the questionnaire to ask “must know” questions as opposed to “nice to know” questions. Essential questions relate to the numbers of patients with the specific type of disease treated by the clinic and investigator each month or year who meet the inclusion criteria. Be precise in each question to get a response in a number, percentage, or range of numbers. Be precise in the time you are asking about (e.g., per week, per month, per year). View the investigator’s evidence if possible.

Assessments to Be Made after the Site Data Are Collected

After all of these data are collected, it will be necessary to combine and interpret the data. Some of the essential questions to address are to determine:

The total number of sites required for the trial

Which countries will be best to conduct the trial in

The number of sites to have in each of the included countries

If any information requires the protocol to be modified

Any issues or problems raised during this feasibility evaluation

The data collected and decisions reached will make it more likely that the trial will be able to be conducted within the timeframe one estimates.

Key Principles to Achieve a Successful Multinational Trial

Most of the critical factors for achieving a successful multinational trial are well-known to drug development professionals and do not contain any surprises. The difference among companies and development professionals lies in how well they pay attention to the trial’s details and how well they are able to ensure that these principles are followed in practice.

Work with vendors (e.g.,

CROs) who have offices in most or all of the countries included in the trial, and ensure that the vendor has local staff who are experienced in running multinational clinical trials in their country (e.g., in terms of legal, regulatory, and investigator interactions). Ensure that the vendor interacts with their offices in other countries in a seamless way.

Ensure that an international communications plan is created and followed by all groups involved in the trial.

Ensure that any cultural issues are addressed.

Ensure there are international project teams that meet regularly, that communications are frequent and efficient, and that any problems are addressed promptly.

Train all staff as needed and include important face-to-face meetings with local project managers.

Use technology that is appropriate and well understood by everyone in the trial infrastructure, whether it is high- or lowtech or a combination of both. Do not use e-technology that is not well accepted and understood by all people who will use it (including patients), and ensure that everyone is trained in the use of all technology and tested as to their proficiency with it.

Have a centralized process for data collection and data management.

Offer local language help desk support for all sites.

Create a dispute resolution system that facilitates the rapid identification, discussion, and resolution of any issues that arise.

These are not meant to be a complete list of the most essential principles but examples of those that must be considered carefully whenever a multinational clinical trial is being planned and implemented.

DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA AND CLASSIFICATION SYSTEMS

Different Criteria are Used in Various Countries to Diagnose Many Diseases

Relatively little attention has been given in the world’s medical literature to whether a given patient would be diagnosed the same way in different countries (and even in different cultural regions within a country). If there are differences in how patients are diagnosed, then it would be relevant to ask why these differences occur; whether these differences would influence the conduct of multinational clinical trials and epidemiological research; and of course, what the therapeutic implications of such differences might be.

Different criteria are used among countries to diagnose many diseases. The criteria may be established by:

Area Where Many Differences in Diagnostic Criteria Exist

The therapeutic area most affected by differences in diagnostic criteria is psychiatry. This chapter mentions some of the factors that influence differences in patient diagnoses, systems used to classify diseases, and the implications of these differences for clinical trials and epidemiological research. Some differences among physicians in how they treat their patients in routine medical practice are presented.

Factors Influencing Patient Diagnoses

There is a tradition in medicine that diagnoses should be based on the patient’s history and physical examination and that laboratory tests should be used only to confirm a diagnosis. However, physicians are tending to rely more and more on laboratory tests to establish diagnoses, not just to confirm them. Experienced older physicians sometimes decry the decreasing ability of younger physicians to make a clinical diagnosis solely from a patient’s history and physical alone and the increasing dependence of many younger physicians on laboratory tests to make diagnoses. Nonetheless, some medical diagnoses (e.g., hypochloremia, hypernatremia) may only be confirmed or even made using laboratory data. Each physician uses a different weighting system in his mind for integrating data from a patient’s history, physical examination, and laboratory tests in reaching a diagnosis.

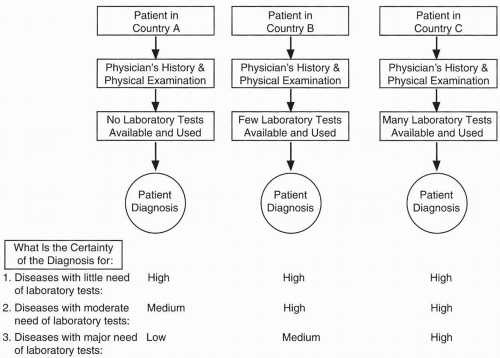

Diagnostic accuracy decreases if the appropriate laboratory tests are unavailable. Even excellent physicians have no greater ability to confirm many diagnoses if critical laboratory tests needed to make a definitive diagnosis are unavailable in their country or region.

Figure 68.1 illustrates this point. Numerous factors that affect patient diagnoses are listed in

Table 68.2.

Diagnostic Tools and Measures Used in Different Countries

Blood pressure is universally measured with a sphygmomanometer, although different types of sphygmomanometers (e.g., manual, electric, automatic cuff inflation) abound. Even though these instruments have varying degrees of reliability and the people using them may have a wide range of experience and expertise, the results obtained are generally quite similar. Partly as a result, the criteria for diagnosing mild hypertension are also approximately the same worldwide.

Certain medical instruments are also believed to be accurate in helping to diagnose various diseases (e.g., stethoscopes used to listen to heart sounds and to diagnose certain cardiac problems, and electroencephalograms used to diagnose many types of epilepsies), but the evidence is less clear if the physician or other healthcare professional is not adequately trained and experienced.

It is important to ask what will be the precision and accuracy of results obtained with these instruments across countries because, in the above two examples, the major factor affecting diagnosis is the experience and expertise of the physician who uses the instrument and interprets the data.

Development of Worldwide Diagnostic Classification Systems

Various groups that have developed international diagnostic classifications are collaborating to reduce differences between their systems. The impetus for this is the need to standardize the regulatory review of adverse events that have been classified using quite different systems. This move toward harmonization is encouraging, although different perspectives persist on how to view many diseases, and it is uncertain whether a single approach can be found for diagnosing and treating some diseases. Examples are plentiful when one appreciates how differently many diseases are defined in different countries (

Payer 1988).

The

ICD-10 classification system approved by the World Health Assembly is the best known and most widely used system for classifying diseases. The World Health Organization’s Division of Mental Health and the

US Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration conducted a worldwide review and assessment of alcohol, drug abuse, and mental health disorder diagnosis and classification (

Robins et al. 1988). The goal has been “to allow investigators to study mental disorders in different populations by means of an instrument that produces comparable results across cultures and languages … it will allow principal diagnoses to be made according to

ICD and several other systems.”