Fasciotomy

Jonathan L. Eliason

The basis for learning the anatomy of the lower extremity, as it relates to fasciotomy, lies in a thorough understanding of the osseofascial boundaries that surround the muscles, blood vessels, and nerves. These boundaries are nonelastic, and form compartments within the extremity. When the pressure within a given compartment impairs perfusion across tissue capillary beds, a compartment syndrome will ensue. This syndrome results in anoxia on a cellular level, and, if left untreated, a progressive loss of function until ischemic necrosis of the tissue occurs. This is true whether the compartment is located in the upper extremity, lower extremity, or abdomen. This chapter will limit its focus to fasciotomy of the lower extremity. Included will be fasciotomies performed for the prevention and/or treatment of compartment syndrome in the gluteal, thigh, and calf regions.

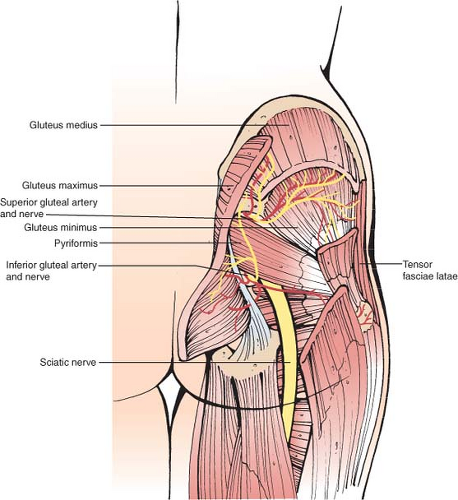

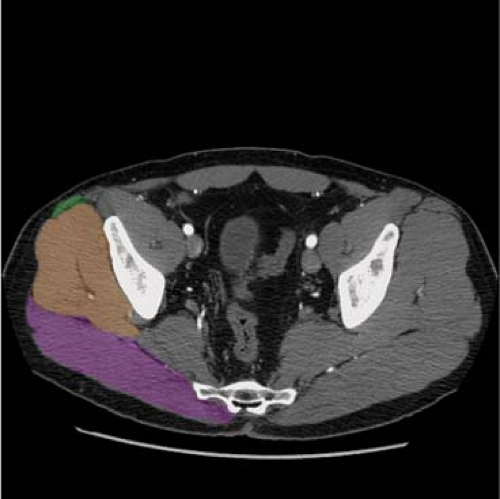

Gluteal Compartment Anatomy

The gluteal compartment is commonly thought of as a single compartment. However, the fascial boundaries really form three distinct compartments, each surrounding a primary muscle group. The largest compartment surrounds the gluteus maximus. The next compartment surrounds both the gluteus medius and minimus muscles. Finally, a third smaller compartment includes only the tensor fascia lata (Fig. 1). The sciatic nerve is the most notable neurovascular structure affected by the gluteal compartment syndrome, and it lies under the gluteus maximus muscle, exiting from the inferior border of the piriformis muscle. The inferior gluteal artery and nerve, which supply the gluteus maximus muscle, and superior gluteal artery and nerve, which, through a complex branching pattern supply the remaining compartments, are also noteworthy (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1. Axial cut computed tomographic (CT) pelvis denoting the gluteus maximus compartment in purple, gluteus medius/minimus compartment in orange, and tensor fascia lata compartment in green. |

Thigh Compartment Anatomy

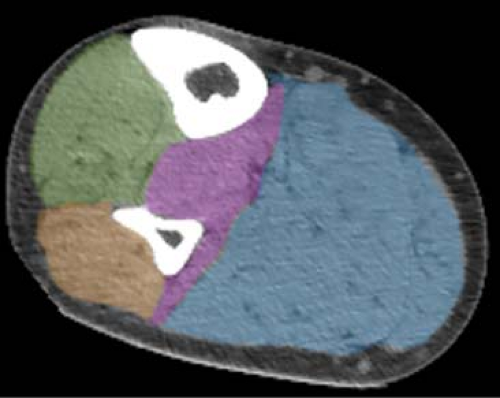

Three functional and osseofascial boundaries are present in the thigh as well. The anterior compartment contains the quadriceps, sartorius, iliopsoas, and pectineus muscles. This compartment also contains the femoral artery and vein, as well as the femoral, and lateral femoral cutaneous nerves. The posterior compartment contains the biceps femoris, semimembranosus, and semitendinosus muscles, as well as the posterior portion of the abductor magnus muscle. The sciatic nerve lies within this compartment. The medial compartment includes the gracilis, adductor longus, adductor brevis, most of the adductor magnus, and the obturator externus muscles. The obturator artery and vein and obturator nerve lie within this compartment (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Axial cut computed tomography of the right thigh denoting the medial compartment in purple, posterior compartment in orange, and anterior compartment in green. |

Fig. 4. Lateral exposure from a two-incision leg fasciotomy demonstrating the superficial peroneal nerve branch coursing toward the foot after exiting the fascia of the lateral compartment. |

Calf Compartment Anatomy

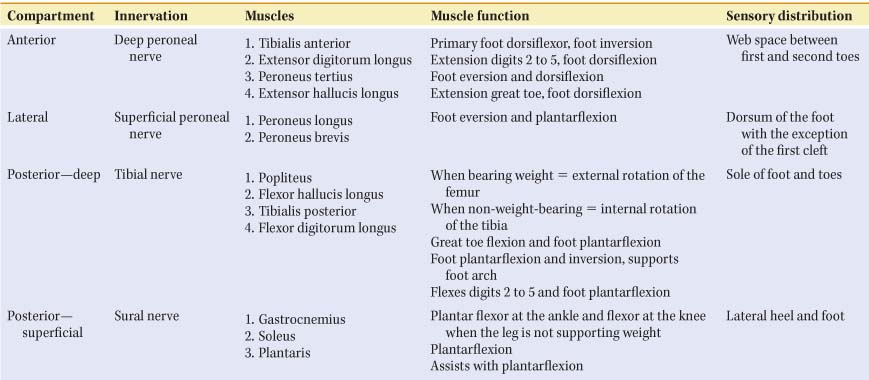

The four compartments of the calf are the anterior, lateral, superficial posterior, and deep posterior. The anterior compartment is bordered by the lateral aspect of the tibia, the interosseous membrane, and the intermuscular septum between the anterior and lateral compartments, which is partially contiguous with the fibula. The muscles that produce dorsiflexion of the foot and toes are contained within this compartment. Neurovascular structures in the anterior compartment include the anterior tibial artery and veins and the deep peroneal nerve. The lateral compartment boundaries include the anterior intermuscular septum, the fibula medially, and the posterior intermuscular septum. The muscles controlling eversion of the foot are contained within this compartment. The superficial branch of the peroneal nerve courses through the lateral compartment until it exits the fascia typically 10 to 12 cm superior to the lateral malleolus (Fig. 4). This nerve is particularly susceptible to harm during fasciotomy, and results in altered sensation over the dorsum of the foot if injured. The superficial posterior compartment contains the gastrocnemius muscle and soleus muscle, and is surrounded by the deep fascia of the calf, except anteriorly, where this fascial plane joins the posterior intermuscular septum. The deep posterior compartment is the most difficult anatomic compartment in the leg to surgically expose. It is bounded by the tibia, interosseous membrane, and fibula along its anteromedial and anterolateral extent. A small component is bounded medially by the deep fascia of the leg, with the remainder posteriorly being surrounded by the posterior intermuscular septum. The long flexors of the toes are included in this compartment, as well as the posterior tibial and peroneal vessels. The tibial nerve also lies within this compartment (Fig. 5).

Gluteal Compartment Syndrome

Within the lower extremity, gluteal compartment syndrome is the least commonly reported location for compartment syndrome. The most common cause for compartment syndrome in this location is a patient with prolonged pressure over the gluteal region, such as an unconscious or severely traumatized patient, or a patient with prolonged positioning for a surgical procedure. Musculoskeletal trauma is the

next most common cause of this rare syndrome, with motor vehicle collisions and explosive/concussive mechanisms being included in this category. Vascular specific causes may also occur, such as an Ehlers–Danlos patient with spontaneous bleeding from a gluteal artery aneurysm, or gluteal compartment syndrome following open abdominal aortic aneurysm repair.

next most common cause of this rare syndrome, with motor vehicle collisions and explosive/concussive mechanisms being included in this category. Vascular specific causes may also occur, such as an Ehlers–Danlos patient with spontaneous bleeding from a gluteal artery aneurysm, or gluteal compartment syndrome following open abdominal aortic aneurysm repair.

Table 1 Compartment Anatomy of the Leg | |

|---|---|

|

The majority of patients presenting with this syndrome are unable to give a history, so physical examination findings become extremely important. Almost uniformly, patients with gluteal compartment syndrome have a massively swollen and extremely firm buttock as part of their presentation. If the patient is able to give a history, symptoms may include hypesthesia or increasing pain in the region of the injury, or a nerve deficit in the leg correlating to the sciatic nerve distribution. Finally, due to the large mass of muscle in the gluteal compartments, if elevated compartment pressures and/or the injury itself results in significant muscle injury, laboratory findings typically include marked elevation of creatine phosphokinase (CPK) enzyme levels and myoglobinuria from rhabdomyolysis, with the subsequent potential for renal failure.

Thigh Compartment Syndrome

Acute compartment syndrome of the thigh is also rare. Blunt trauma is the most common cause, with nearly half of the patients with thigh compartment syndrome having an associated femur fracture. Penetrating trauma, vascular injury, prolonged intraoperative positioning, or external compression from a comatose patient may also cause this syndrome. All patients present with a tensely swollen thigh. Noncomatose patients complain of intolerable pain, with focal paresthesias or paresis also being common. A pulseless extremity may also be a component of the patient presentation for thigh compartment syndrome in the acute setting, occurring in one out of five patients. As one would expect, a pulseless extremity occurs more commonly when the compartment syndrome includes a femur fracture. High CPK levels are less common in the thigh compartment syndrome than in the gluteal compartment syndrome, but can certainly be a component of the presentation.

Calf Compartment Syndrome

Compartment syndrome of the calf is the most common type of lower extremity compartment syndrome. Blunt and penetrating trauma are common causes, again being frequently associated with tibial fractures, but ischemia reperfusion also contributes significantly to the prevalence of this disease process. National data suggest that >4% of patients presenting to U.S. hospitals with diagnosis codes consistent with acute limb ischemia undergo a fasciotomy. A high index of suspicion is critical in making the clinical diagnosis of compartment syndrome. In the obtunded patient, firmness of the compartment is the earliest sign of this syndrome, with loss of pulses being rare and a late finding. In the awake patient, excessive pain, palpable tightness, and severe pain with passive stretch of the muscles are common early findings, with paresthesias, progressive paralysis, and changes in pulse examination being late findings. Understanding which muscles and nerves travel within each of the four different compartments can aid in making the clinical diagnosis of which compartments are affected (Table 1). Although rhabdomyolysis can occur with this syndrome, it is quite rare. History has shown that revascularization of a densely ischemic leg, especially in the setting of neurological changes, will likely result in significant reperfusion injury, muscle edema, and compartment syndrome. In such a patient, prophylactic fasciotomy is often performed in order to prevent this syndrome.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree