F

Facial pain

Facial pain may result from various neurologic, vascular, or infectious disorders. The most common cause of facial pain is trigeminal neuralgia (tic douloureux). In this disorder, intense, paroxysmal facial pain may occur along the pathway of a specific facial nerve or nerve branch, usually cranial nerve V (trigeminal nerve) or cranial nerve VII (facial nerve). Pain can also be referred to the face in disorders of the ear, nose, paranasal sinuses, teeth, neck, and jaw.

Atypical facial pain is a constant burning pain with limited distribution at onset; it typically spreads to the rest of the face and may involve the neck or back of the head as well. This type of facial pain is common in middle-aged women, especially those who are clinically depressed.

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Begin by characterizing the patient’s facial pain. Is it stabbing, throbbing, or dull? When did it begin? How long has it lasted? What relieves or worsens it? Ask the patient to point to the painful area. If facial pain is recurrent, have him describe a typical episode. Review his medical and dental history, noting especially previous head trauma, dental disease, and infection. Carefully examine the face and head. Inspect the ear for vesicles and changes in the tympanic membrane to rule out referred ear pain. Inspect the nose for deformity or asymmetry. Evaluate the condition of the mucous membranes and septum as well as the size and shape of the turbinates. Characterize any secretions. Palpate the frontal, ethmoid, and maxillary sinuses for tenderness and swelling.

Evaluate oral hygiene by inspecting the teeth for caries, percussing any diseased teeth for pain, and asking the patient about any sensitivity to hot, cold, or sweet liquids or foods. Have him open and close his mouth as you palpate the temporomandibular joint for tenderness, spasm, locking, and crepitus.

Examine the function of cranial nerves V and VII. To evaluate cranial nerve V, instruct the patient to clench his teeth. Then palpate the temporal and masseter muscles and evaluate muscle contraction. Test pain and sensation on his forehead, cheeks, and jaw. Next, test the corneal reflex by lightly touching the cornea with a piece of cotton.

To evaluate cranial nerve VII, inspect the face for symmetry and then have the patient perform facial movements that demonstrate facial muscle strength—raising his eyebrows, frowning, showing his teeth, closing his eyes tightly, and wrinkling his nose. (See Major nerve pathways of the face, page 288.)

MEDICAL CAUSES

♦ Angina pectoris. Occasionally, jaw pain may indicate angina pectoris. A more comprehensive history and evaluation is needed to determine cardiac origin.

♦ Dental caries. Caries in the mandibular molars can produce ear, preauricular, and temporal pain; caries in the maxillary teeth can produce

maxillary, orbital, retro-orbital, and parietal pain. Other dental causes of facial pain are an abnormal bite and faulty dentures. Facial pain related to chewing or temperature changes may suggest dental problems.

maxillary, orbital, retro-orbital, and parietal pain. Other dental causes of facial pain are an abnormal bite and faulty dentures. Facial pain related to chewing or temperature changes may suggest dental problems.

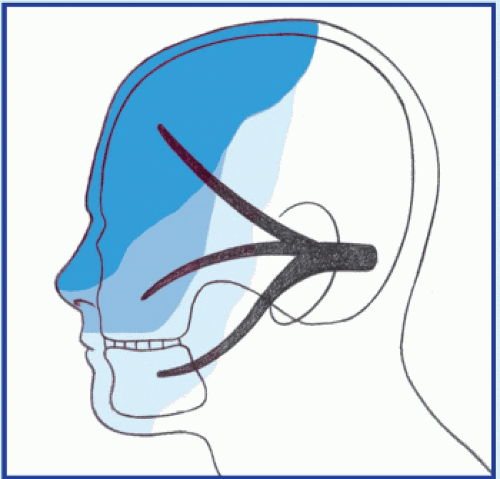

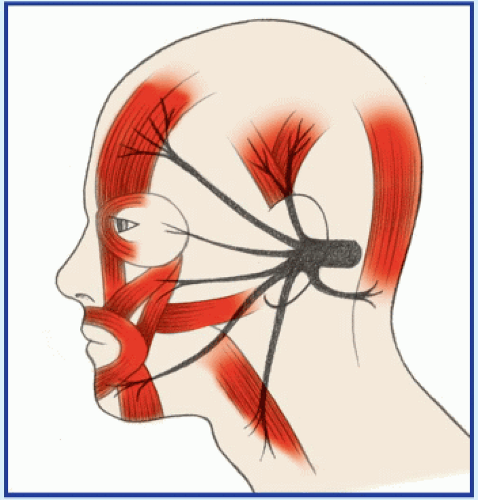

Major nerve pathways of the face

Cranial nerve V has three branches. The ophthalmic branch supplies sensation to the anterior scalp, forehead, upper nose, and cornea. The maxillary branch supplies sensation to the midportion of the face, lower nose, upper lip, and mucous membrane of the anterior palate. The mandibular branch supplies sensation to the lower face, lower jaw, mucous membrane of the cheek, and base of the tongue.

Cranial nerve VII innervates the facial muscles. Its motor branch controls the muscles of the forehead, eye orbit, and mouth.

♦ Glaucoma. In glaucoma, an important cause of facial pain, the pain is usually located in the periorbital region.

♦ Glossopharyngeal neuralgia. The pain in this uncommon disorder is similar to that of trigeminal neuralgia. It typically occurs in the throat near the tonsillar fossa and may radiate to the ear and posterior aspect of the tongue. It may be aggravated by swallowing, chewing, talking, or yawning. No underlying structural abnormality is usually present.

♦ Herpes zoster oticus (Ramsay Hunt syndrome). This disorder causes severe pain around the ear, followed by vesicles in the ear and occasionally on the oral mucosa, tonsils, and posterior tongue. Other findings may include hearing loss, vertigo, and transient ipsilateral facial paralysis.

♦ Multiple sclerosis (MS). Facial pain in MS may resemble that of trigeminal neuralgia and is accompanied by jaw and facial weakness. Other common findings include visual blurring, diplopia, and nystagmus; sensory impairment such as paresthesia; generalized muscle weakness and gait abnormalities; urinary disturbances; and emotional lability.

♦ Postherpetic neuralgia. Burning, itching, prickly pain persists along any of the three trigeminal nerve divisions and worsens with contact or movement. Mild hypoesthesia or paresthesia and vesicles affect the area before the onset of pain.

♦ Sinus cancer. In ethmoid sinus cancer, facial pain is a late symptom, preceded by exophthalmos. In maxillary sinus cancer, persistent pain along the second division of cranial nerve V is a late symptom.

♦ Sinusitis (acute). Acute maxillary sinusitis produces unilateral or bilateral pressure, fullness, or burning pain over the cheekbone and upper teeth and around the eyes. Bending over increases the pain. Other findings include nasal congestion and purulent discharge; red, swollen nasal mucosa; tenderness and swelling over the cheekbone; fever; and malaise.

Acute frontal sinusitis commonly produces severe pain above or around the eyes, which worsens when the patient is in a supine position. It also causes nasal obstruction, inflamed

nasal mucosa, fever, and tenderness and swelling above the eyes.

nasal mucosa, fever, and tenderness and swelling above the eyes.

Acute ethmoid sinusitis produces pain at or around the inner corner of the eye and sometimes temporal headaches. Other findings include nasal congestion, purulent rhinorrhea, fever, and tenderness at the medial edge of the eye.

In acute sphenoid sinusitis, a deep-seated pain persists behind the eyes or nose or on the top of the head. The pain increases on bending forward and may be accompanied by fever.

♦ Sinusitis (chronic). Chronic maxillary sinusitis produces a feeling of pressure below the eyes or a chronic toothache. Discomfort typically worsens throughout the day. Nasal congestion and tenderness over the cheekbone are usually mild.

Chronic frontal sinusitis produces a persistent low-grade pain above the eyes. The patient usually has a history of trauma or long-standing inflammation.

Chronic ethmoid sinusitis is characterized by nasal congestion, an intermittent purulent nasal discharge, and low-grade discomfort at the medial corners of the eyes. Also common are recurrent sore throat, halitosis, ear fullness, and involvement of the other sinuses.

A low-grade, diffuse headache or retroorbital discomfort is common in chronic sphenoid sinusitis.

♦ Sphenopalatine neuralgia. In this type of neuralgia, unilateral deep, boring pain occurs below the ear and may radiate to the eye, ear, cheek, nose, palate, maxillary teeth, temple, back of the head, neck, or shoulder. Attacks also cause increased tearing and salivation, rhinorrhea, a sensation of fullness in the ear, tinnitus, vertigo, taste disturbances, pruritus, and shoulder stiffness or weakness.

♦ Temporal arteritis. Unilateral pain occurs behind the eye or in the scalp, jaw, tongue, or neck. A typical episode consists of a severe throbbing or boring temporal headache with redness, swelling, and nodulation of the temporal artery.

♦ Temporomandibular joint syndrome. In this syndrome, intermittent pain, usually unilateral, is described as a severe, dull ache or an intense spasm that radiates to the cheek, temple, lower jaw, ear, or mastoid area. Associated findings include trismus, malocclusion, and clicking, crepitus, and tenderness in the temporomandibular joint.

♦ Trigeminal neuralgia. Paroxysms of intense pain, lasting up to 15 minutes, shoot along any or all of the three branches of the trigeminal nerve. The pain can be triggered by touching the nose, cheek, or mouth; by being exposed to hot or cold weather; by consuming hot or cold foods or beverages; or even by smiling or talking. Between attacks, the pain may diminish to a dull ache or may disappear. This disorder is most common in middle and later life, affecting more women than men.

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

Prepare the patient for diagnostic tests, such as sinus, skull, or dental X-rays; sinus transillumination; and intracranial or sinus computed tomography scans. Give pain medications, and apply direct heat or administer a muscle relaxant to ease muscle spasms. Provide a humidifier, vaporizer, or decongestant to relieve nasal or sinus congestion.

PEDIATRIC POINTERS

Facial pain may be difficult to assess in a young child if his language skills aren’t sufficiently developed for him to describe the pain. Be alert for subtle signs of pain, such as facial rubbing, irritability, or poor eating habits.

PATIENT COUNSELING

If appropriate, instruct the patient with trigeminal neuralgia to avoid stressful situations, hot and cold foods, and sudden jarring movements, which can trigger painful attacks.

Fasciculations

Fasciculations are local muscle contractions representing the spontaneous discharge of a muscle fiber bundle innervated by a single motor nerve filament. These contractions cause visible dimpling or wavelike twitching of the skin, but they aren’t strong enough to cause a joint to move. Their frequency ranges from once every several seconds to two or three times per second; occasionally, myokymia—continuous, rapid fasciculations that cause a rippling effect—may occur. Because fasciculations are brief and painless, they commonly go undetected or are ignored.

Benign, nonpathologic fasciculations are common and normal. They often occur in tense, anxious, or overtired people and typically affect

the eyelid, thumb, or calf. However, fasciculations may also indicate a severe neurologic disorder, most notably a diffuse motor neuron disorder that causes loss of control over muscle fiber discharge. They’re also an early sign of pesticide poisoning.

the eyelid, thumb, or calf. However, fasciculations may also indicate a severe neurologic disorder, most notably a diffuse motor neuron disorder that causes loss of control over muscle fiber discharge. They’re also an early sign of pesticide poisoning.

Begin by asking the patient about the nature, onset, and duration of the fasciculations. If the onset was sudden, ask about any precipitating events, such as exposure to pesticides. Pesticide poisoning, although uncommon, is a medical emergency requiring prompt and vigorous intervention. You may need to maintain airway patency, monitor vital signs, give oxygen, and perform gastric lavage or induce vomiting.

Begin by asking the patient about the nature, onset, and duration of the fasciculations. If the onset was sudden, ask about any precipitating events, such as exposure to pesticides. Pesticide poisoning, although uncommon, is a medical emergency requiring prompt and vigorous intervention. You may need to maintain airway patency, monitor vital signs, give oxygen, and perform gastric lavage or induce vomiting.HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

If the patient isn’t in severe distress, find out if he has experienced any sensory changes, such as paresthesia, or any difficulty speaking, swallowing, breathing, or controlling bowel or bladder function. Ask him if he’s in pain.

Explore the patient’s medical history for neurologic disorders, cancer, and recent infections. Also, ask him about his lifestyle, especially stress at home, on the job, or at school.

Ask the patient about his dietary habits and for a recall of his food and fluid intake in the recent past because electrolyte imbalances may also cause muscle twitching.

Perform a physical examination, looking for fasciculations while the affected muscle is at rest. Observe and test for motor and sensory abnormalities, particularly muscle atrophy and weakness, and decreased deep tendon reflexes. If you note these signs and symptoms, suspect motor neuron disease, and perform a comprehensive neurologic examination.

MEDICAL CAUSES

♦ Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. In this progressive motor neuron disease, coarse fasciculations usually begin in the small muscles of the hands and feet, and then spread to the forearms and legs. Widespread, symmetrical muscle atrophy and weakness may result in dysarthria; difficulty chewing, swallowing, and breathing; and, occasionally, choking and drooling.

♦ Bulbar palsy. Fasciculations of the face and tongue commonly appear early in bulbar palsy. Progressive signs and symptoms include dysarthria, dysphagia, hoarseness, and drooling. Eventually, weakness spreads to the respiratory muscles.

♦ Guillain-Barré syndrome. Fasciculations may occur in Gullain-Barré syndrome, but the cardinal neurologic symptom is muscle weakness, which typically begins in the legs and spreads quickly to the arms and face. Other findings include paresthesia, incontinence, footdrop, tachycardia, dysphagia, and respiratory insufficiency.

♦ Herniated disk. Fasciculations of the muscles innervated by compressed nerve roots may be widespread and profound, but the hallmark of a herniated disk is severe low back pain that may radiate unilaterally to the leg. Coughing, sneezing, bending, and straining exacerbate the pain. Related effects include muscle weakness, atrophy, and spasms; paresthesia; footdrop; steppage gait; and hypoactive deep tendon reflexes in the leg.

♦ Poliomyelitis (spinal paralytic). Coarse fasciculations, usually transient but occasionally persistent, accompany progressive muscle weakness, spasms, and atrophy in this disorder. The patient may also exhibit decreased reflexes, paresthesia, coldness and cyanosis in the affected limbs, bladder paralysis, dyspnea, elevated blood pressure, and tachycardia.

♦ Spinal cord tumor. Fasciculations, muscle atrophy, and cramps may develop asymmetrically at first and then bilaterally as cord compression progresses. Motor and sensory changes distal to the tumor include weakness or paralysis, areflexia, paresthesia, and a tightening band of pain. Bowel and bladder control may be lost.

♦ Syringomyelia. In this disorder, fasciculations may occur along with Charcot’s joints, areflexia, muscle atrophy, and deep, aching pain. Additional findings include thoracic scoliosis and loss of pain and temperature sensation over the neck, shoulders, and arms.

OTHER CAUSES

♦ Pesticide poisoning. Ingestion of organophosphate or carbamate pesticides commonly produces acute onset of long, wavelike fasciculations and muscle weakness that rapidly progresses to flaccid paralysis. Other common effects include nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, loss of bowel and bladder control, hyperactive bowel sounds, and abdominal cramping. Cardiopulmonary findings include bradycardia, dyspnea or bradypnea, and pallor or cyanosis. Seizures, vision disturbances (pupillary constriction or

blurred vision), and increased secretions (tearing, salivation, pulmonary secretions, or diaphoresis) may also occur.

blurred vision), and increased secretions (tearing, salivation, pulmonary secretions, or diaphoresis) may also occur.

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

Prepare the patient for diagnostic studies, such as spinal X-rays, myelography, computed tomography scan, magnetic resonance imaging, and electromyography with nerve conduction velocity tests. Prepare the patient for laboratory tests such as serum electrolyte levels. Help the patient with progressive neuromuscular degeneration perform activities of daily living, and provide appropriate assistive devices.

PEDIATRIC POINTERS

Fasciculations, particularly of the tongue, are an important early sign of Werdnig-Hoffmann disease.

PATIENT COUNSELING

Teach effective stress management techniques to the patient with stress-induced fasciculations.

Fatigue

Fatigue is a feeling of excessive tiredness, lack of energy, or exhaustion accompanied by a strong desire to rest or sleep. This common symptom is distinct from weakness, which involves the muscles, but may accompany it.

Fatigue is a normal and important response to physical overexertion, prolonged emotional stress, and sleep deprivation. However, it can also be a nonspecific symptom of a psychological or physiologic disorder, especially viral or bacterial infection and endocrine, cardiovascular, or neurologic disease.

Fatigue reflects both hypermetabolic and hypometabolic states in which nutrients needed for cellular energy and growth are lacking because of overly rapid depletion, impaired replacement mechanisms, insufficient hormone production, or inadequate nutrient intake or metabolism.

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Obtain a careful history to identify the patient’s fatigue pattern. Fatigue that worsens with activity and improves with rest generally indicates a physical disorder; the opposite pattern, a psychological disorder. Fatigue lasting longer than 4 months, constant fatigue that’s unrelieved by rest, and transient exhaustion that quickly gives way to bursts of energy are findings associated with psychological disorders.

Ask about related symptoms and any recent viral or bacterial illness or stressful changes in lifestyle. Explore nutritional habits and any appetite or weight changes. Carefully review the patient’s medical and psychiatric history for any chronic disorders that commonly produce fatigue, and ask about a family history of such disorders.

Obtain a thorough drug history, noting use of any narcotic or drug with fatigue as an adverse effect. Ask about alcohol and drug use patterns. Determine the patient’s risk of carbon monoxide poisoning, and ask whether the patient has a carbon monoxide detector.

Observe the patient’s general appearance for overt signs of depression or organic illness. Is he unkempt or expressionless? Does he appear tired or sickly, or have a slumped posture? If warranted, evaluate his mental status, noting especially mental clouding, attention deficits, agitation, or psychomotor retardation.

MEDICAL CAUSES

♦ Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Besides fatigue, this syndrome may cause fever, night sweats, weight loss, diarrhea, and a cough, followed by several concurrent opportunistic infections.

♦ Adrenocortical insufficiency. Mild fatigue, the hallmark of this disorder, initially appears after exertion and stress but later becomes more severe and persistent. Weakness and weight loss typically accompany GI disturbances, such as nausea, vomiting, anorexia, abdominal pain, and chronic diarrhea; hyperpigmentation; orthostatic hypotension; and a weak, irregular pulse.

♦ Anemia. Fatigue after mild activity is commonly the first symptom of anemia. Associated findings vary but generally include pallor, tachycardia, and dyspnea.

♦ Anxiety. Chronic, unremitting anxiety invariably produces fatigue, often characterized as nervous exhaustion. Other persistent findings include apprehension, indecisiveness, restlessness, insomnia, trembling, and increased muscle tension.

♦ Cancer. Unexplained fatigue is commonly the earliest sign of cancer. Related findings reflect the type, location, and stage of the tumor and typically include pain, nausea, vomiting,

anorexia, weight loss, abnormal bleeding, and a palpable mass.

anorexia, weight loss, abnormal bleeding, and a palpable mass.

♦ Chronic fatigue syndrome. This syndrome, whose cause is unknown, is characterized by incapacitating fatigue. Other findings are sore throat, myalgia, and cognitive dysfunction.

♦ Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. The earliest and most persistent symptoms of this disease are progressive fatigue and dyspnea. The patient may also experience a chronic and usually productive cough, weight loss, barrel chest, cyanosis, slight dependent edema, and poor exercise tolerance.

♦ Cirrhosis. Severe fatigue typically occurs late in this disorder, accompanied by weight loss, bleeding tendencies, jaundice, hepatomegaly, ascites, dependent edema, severe pruritus, and decreased level of consciousness.

♦ Cushing’s syndrome (hypercortisolism). This disorder typically causes fatigue, related in part to accompanying sleep disturbances. Cardinal signs include truncal obesity with slender extremities, buffalo hump, moon face, purple striae, acne, and hirsutism; increased blood pressure and muscle weakness may also occur.

♦ Depression. Persistent fatigue unrelated to exertion nearly always accompanies chronic depression. Associated somatic complaints include headache, anorexia (occasionally, increased appetite), constipation, and sexual dysfunction. The patient may also experience insomnia, slowed speech, agitation or bradykinesia, irritability, loss of concentration, feelings of worthlessness, and persistent thoughts of death.

♦ Diabetes mellitus. Fatigue, the most common symptom of this disorder, may begin insidiously or abruptly. Related findings include weight loss, blurred vision, polyuria, polydipsia, and polyphagia.

♦ Heart failure. Persistent fatigue and lethargy characterize this disorder. Left-sided heart failure produces exertional and paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, orthopnea, and tachycardia. Rightsided heart failure produces jugular vein distention and possibly a slight but persistent nonproductive cough. In both types, later signs and symptoms include mental status changes, nausea, anorexia, weight gain and, possibly, oliguria. Cardiopulmonary findings include tachypnea, inspiratory crackles, palpitations and chest tightness, hypotension, narrowed pulse pressure, ventricular gallop, pallor, diaphoresis, clubbing, and dependent edema.

♦ Hypopituitarism. Fatigue, lethargy, and weakness usually develop slowly. Other insidious effects may include irritability, anorexia, amenorrhea or impotence, decreased libido, hypotension, dizziness, headache, visual disturbances, and cold intolerance.

♦ Hypothyroidism. Fatigue occurs early in this disorder along with forgetfulness, cold intolerance, weight gain, metrorrhagia, and constipation.

♦ Infection. Fatigue is commonly the most prominent symptom—and sometimes the only one—in a chronic infection. Low-grade fever and weight loss may accompany signs and symptoms that reflect the type and location of the infection, such as burning on urination or swollen, painful gums. Subacute bacterial endocarditis is an example of a chronic infection that causes fatigue and acute hemodynamic decompensation.

In an acute infection, brief fatigue typically accompanies headache, anorexia, arthralgia, chills, high fever, and such infection-specific signs as a cough, vomiting, or diarrhea.

♦ Influenza type A H1N1 virus (swine flu). Influenza type A H1N1, or swine flu, is a respiratory disease of pigs caused by type A influenza virus. Swine flu viruses cause high levels of illness and low death rates in pigs. Swine flu viruses normally don’t infect humans. However, sporadic human infections with swine flu have occurred. Most commonly, these cases occur in persons with direct exposure to pigs. The virus has changed slightly and is known as H1N1 flu. Outbreaks of H1N1 flu in 2009 showed that the virus can be transmitted from person to person, causing transmission across the globe. The H1N1 flu is similar to influenza, and causes illness and in some cases death. The symptoms of swine flu include fatigue, fever, nonproductive cough, myalgia, chills, headache, and vomiting. The use of antiviral drugs is recommended to treat H1N1 flu.

♦ Lyme disease. Besides fatigue and malaise, signs and symptoms of this tick-borne disease include intermittent headache, fever, chills, an expanding red rash, and muscle and joint aches. Later, patients may develop arthritis, fluctuating meningoencephalitis, and cardiac abnormalities, such as a brief, fluctuating atrioventricular heart block.

♦ Malnutrition. Easy fatigability, lethargy, and apathy are common findings in patients with protein-calorie malnutrition. Patients may also

exhibit weight loss, muscle wasting, sensations of coldness, pallor, edema, and dry, flaky skin.

exhibit weight loss, muscle wasting, sensations of coldness, pallor, edema, and dry, flaky skin.

♦ Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). MRSA is a strain of staphylococcus that’s resistant to antibiotics commonly used to treat staphylococcal infections. The incidence of MRSA has greatly increased in recent years. This increase is thought to be related to the increase in antibiotic use in hospital and outpatient settings and the widespread use of hand sanitizers and disinfectants. Older adults and patients with compromised immune systems are at greatest risk for MRSA, although it’s becoming more common in community settings. Patients with MRSA may have a variety of signs and symptoms (most commonly fatigue and fever), depending on where the infection is located.

♦ Myasthenia gravis. The cardinal symptoms of this disorder are easy fatigability and muscle weakness, which worsen as the day progresses. They also worsen with exertion and abate with rest. Related findings depend on the specific muscles affected.

♦ Myocardial infarction. Fatigue can be severe but is typically overshadowed by chest pain. Related findings include dyspnea, anxiety, pallor, cold sweats, increased or decreased blood pressure, and abnormal heart sounds.

♦ Narcolepsy. One or more of the following characterizes this disorder: hypersomnia, hypnagogic hallucinations, cataplexy, sleep paralysis, and insomnia. Fatigue is a common symptom as well.

♦ Popcorn lung disease. Popcorn lung disease occurs in factory workers who experience respiratory symptoms after inhaling butter flavoring chemicals such as diacetyl, used in the manufacture of microwave popcorn. The patient typically complains of gradual onset of a nonproductive cough that worsens over time, progressive shortness of breath, and unusual fatigue. Clinical findings include wheezing, chest pain, fever, night sweats, and weight loss. Bronchiolitis fibrosa obliterans, an irreversible fixed airway obstructive lung disorder, is the most severe condition reported.

♦ Renal failure. Acute renal failure commonly causes sudden fatigue, drowsiness, and lethargy. Oliguria, an early sign, is followed by severe systemic effects: ammonia breath odor, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea or constipation, and dry skin and mucous membranes. Neurologic findings include muscle twitching, personality changes, and altered level of consciousness, which may progress to seizures and coma.

Chronic renal failure produces insidious fatigue and lethargy along with marked changes in all body systems, including GI disturbances, ammonia breath odor, Kussmaul’s respirations, bleeding tendencies, poor skin turgor, severe pruritus, paresthesia, visual disturbances, confusion, seizures, and coma.

♦ Restrictive lung disease. Chronic fatigue may accompany the characteristic signs and symptoms: dyspnea, cough, and rapid, shallow respirations. Cyanosis first appears with exertion; later, even at rest.

♦ Rheumatoid arthritis. Fatigue, weakness, and anorexia precede localized articular findings: joint pain, tenderness, warmth, and swelling along with morning stiffness.

♦ Systemic lupus erythematosus. Fatigue usually occurs along with generalized aching, malaise, low-grade fever, headache, and irritability. Primary signs and symptoms include joint pain and stiffness, butterfly rash, and photosensitivity. Also common are Raynaud’s phenomenon, patchy alopecia, and mucous membrane ulcers.

♦ Thyrotoxicosis. In this disorder, fatigue may accompany characteristic signs and symptoms, including an enlarged thyroid, tachycardia and palpitations, tremors, weight loss despite increased appetite, diarrhea, dyspnea, nervousness, diaphoresis, heat intolerance, amenorrhea and, possibly, exophthalmos.

♦ Valvular heart disease. All types of valvular heart disease commonly produce progressive fatigue and a cardiac murmur. Additional signs and symptoms vary but generally include exertional dyspnea, cough, and hemoptysis.

♦ Vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE) infection. Enterococci are bacteria naturally present in the intestinal tract of all people; however, some strains of enterococci have become resistant to vancomycin. Serious VRE infections may occur in hospitalized patients with such comorbidities as cancer, kidney disease, or immune deficiencies. Elderly patients and those hospitalized for long periods are also at risk for developing VRE infections. Symptoms of VRE infection depend on where the infection is; patients with VRE infections may have diarrhea, fever, and fatigue.

♦ Vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (VRSA). VRSA is a strain of staphylococcus that’s resistant to vancomycin, an antibiotic commonly used to treat staphylococcal

infections. Patients most susceptible to VRSA infections include those with diabetes, kidney disease, or previous infection with MRSA, and those with I.V. catheters. VRSA can be difficult to diagnose because of the patient’s overlying medical problems. Patients with VRSA commonly complain of fatigue and fever that don’t respond to treatment with vancomycin. VRSA is usually diagnosed when cultures are done to see why the patient isn’t responding to vancomycin; after the patient is started on a different antibiotic, the infection improves.

infections. Patients most susceptible to VRSA infections include those with diabetes, kidney disease, or previous infection with MRSA, and those with I.V. catheters. VRSA can be difficult to diagnose because of the patient’s overlying medical problems. Patients with VRSA commonly complain of fatigue and fever that don’t respond to treatment with vancomycin. VRSA is usually diagnosed when cultures are done to see why the patient isn’t responding to vancomycin; after the patient is started on a different antibiotic, the infection improves.

OTHER CAUSES

♦ Carbon monoxide poisoning. Fatigue occurs along with headache, dyspnea, and confusion; apnea and unconsciousness may occur eventually.

♦ Drugs. Fatigue may result from various drugs, notably antihypertensives and sedatives. In those receiving cardiac glycoside therapy, fatigue may indicate toxicity.

♦ Surgery. Most types of surgery cause temporary fatigue, probably from the combined effects of hunger, anesthesia, and sleep deprivation.

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

If fatigue results from organic illness, help the patient determine which daily activities he may need help with and how he should pace himself to ensure sufficient rest. You can help him reduce chronic fatigue by alleviating pain, which may interfere with rest, or nausea, which may lead to malnutrition. He may benefit from referral to a community health nurse or housekeeping service. If fatigue results from a psychogenic cause, refer him for psychological counseling.

PEDIATRIC POINTERS

When evaluating a child for fatigue, ask his parents if they’ve noticed any change in his activity level. Fatigue without an organic cause occurs normally during accelerated growth phases in preschool-age and prepubescent children. However, psychological causes of fatigue must be considered; for example, a depressed child may try to escape problems at home or school by taking refuge in sleep. In the pubescent child, consider the possibility of drug abuse, particularly of hypnotics and tranquilizers.

GERIATRIC POINTERS

Always ask older patients about fatigue because this symptom may be insidious and mask more serious underlying conditions in this age-group. Temporal arthritis, which is much more common in people older than age 60, is usually characterized by fatigue, weight loss, jaw claudication, proximal muscle weakness, headache, visual disturbances, and associated anemia.

PATIENT COUNSELING

Regardless of the cause of fatigue, you may need to help the patient alter his lifestyle to achieve a balanced diet, a program of regular exercise, and adequate rest. Counsel him about setting priorities, keeping a reasonable schedule, and developing good sleep habits. Teach stress management techniques as appropriate.

Fecal incontinence

Fecal incontinence, the involuntary passage of feces, follows any loss or impairment of external anal sphincter control. It can result from various GI, neurologic, and psychological disorders; the effects of drugs; or surgery. In some patients, it may even be a purposeful manipulative behavior.

Fecal incontinence may be temporary or permanent; its onset may be gradual, as in dementia, or sudden, as in spinal cord trauma. Although usually not a sign of severe illness, it can greatly affect the patient’s physical and psychological well-being.

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Ask the patient with fecal incontinence about its onset, duration, and severity and about any discernible pattern—for example, at night or with diarrhea. Note the frequency, consistency, and volume of stools passed within the last 24 hours and obtain a stool specimen. Focus your history taking on GI, neurologic, and psychological disorders.

Let the history guide your physical examination. If you suspect a brain or spinal cord lesion, perform a complete neurologic examination. (See Neurologic control of defecation.) If a GI disturbance seems likely, inspect the abdomen for distention, auscultate for bowel sounds, and percuss and palpate for a mass. Inspect the anal area for signs of excoriation or infection. If not contraindicated, check for fecal impaction, which may be associated with incontinence.

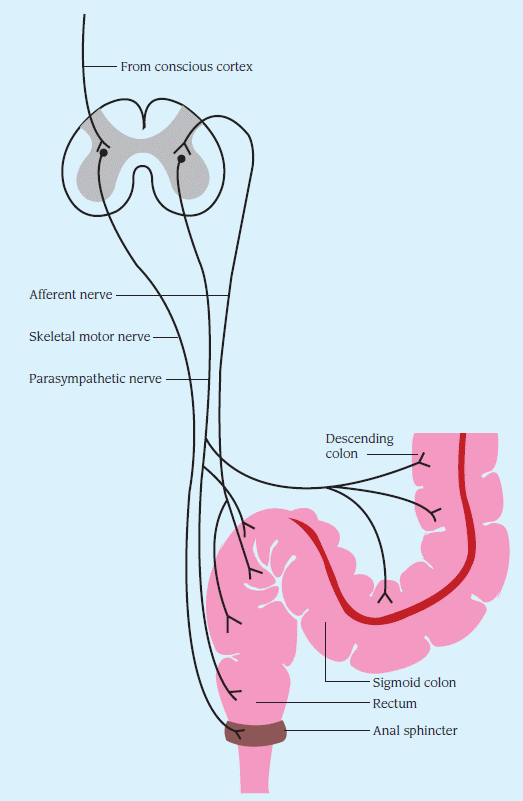

Neurologic control of defecation

Three neurologic mechanisms normally regulate defecation: the intrinsic defecation reflex in the colon, the parasympathetic defecation reflex involving sacral segments of the spinal cord, and voluntary control. Here’s how they interact.

|

Fecal distention of the rectum activates the relatively weak intrinsic reflex, causing afferent impulses to spread through the myenteric plexus, initiating peristalsis in the descending and sigmoid colon and in the rectum. Subsequent movement of feces toward the anus causes receptive relaxation of the internal anal sphincter.

To ensure defecation, the parasympathetic reflex magnifies the intrinsic reflex. Stimulation of afferent nerves in the rectal wall propels impulses through the spinal cord and back to the descending and sigmoid colon, rectum, and anus to intensify peristalsis (see illustration).

However, fecal movement and internal sphincter relaxation cause immediate contraction of the external anal sphincter and temporary fecal retention. At this point, conscious control of the external sphincter either prevents or permits defecation. Except in infants or neurologically impaired patients, this voluntary mechanism further contracts the sphincter to prevent defecation at inappropriate times or relaxes it and allows defecation to occur.

Bowel retraining tips

You can help your patient control fecal incontinence by instituting a bowel retraining program. Here’s how:

♦ Begin by establishing a specific time for defecation. A typical schedule is once a day or once every other day after a meal, usually breakfast. However, be flexible when establishing a schedule, and consider the patient’s normal habits and preferences.

♦ If necessary, help ensure regularity by administering a suppository, either glycerin or bisacodyl, about 30 minutes before the scheduled defecation time. Avoid the routine use of enemas or laxatives because they can cause dependence.

♦ Provide privacy and a relaxed environment to encourage regularity. If “accidents” occur, assure the patient that they’re normal and don’t mean that he has failed in the program.

♦ Adjust the patient’s diet to provide adequate bulk and fiber; encourage him to eat more raw fruits and vegetables and whole grains. Ensure a fluid intake of at least 1 qt (1 L)/day.

♦ If appropriate, encourage the patient to exercise regularly to help stimulate peristalsis.

♦ Be sure to keep accurate intake and elimination records.

MEDICAL CAUSES

♦ Dementia. Any chronic degenerative brain disease can produce fecal as well as urinary incontinence. Associated signs and symptoms include impaired judgment and abstract thinking, amnesia, emotional lability, hyperactive deep tendon reflexes (DTRs), aphasia or dysarthria and, possibly, diffuse choreoathetoid movements.

♦ Gastroenteritis. Severe gastroenteritis may result in temporary fecal incontinence manifested by explosive diarrhea. Nausea, vomiting, and colicky, peristaltic abdominal pain are typical. Other findings include headache, myalgia, and hyperactive bowel sounds.

♦ Head trauma. Disruption of the neurologic pathways that control defecation can cause fecal incontinence. Additional findings depend on the location and severity of the injury and may include decreased level of consciousness, seizures, vomiting, and a wide range of motor and sensory impairments.

♦ Inflammatory bowel disease. Nocturnal fecal incontinence occurs occasionally with diarrhea. Related findings include abdominal pain, anorexia, weight loss, blood in the stool, and hyperactive bowel sounds.

♦ Multiple sclerosis. Fecal incontinence occasionally appears as one of this disorder’s extremely variable signs. Other effects depend on the area of demyelination and may include muscle weakness, ataxia, and paralysis; gait disturbances; sensory impairment, such as paresthesia and genital anesthesia; visual blurring, diplopia, or nystagmus; urinary disturbances; and emotional lability.

♦ Rectovaginal fistula. Fecal incontinence occurs in tandem with uninhibited passage of flatus.

♦ Spinal cord lesion. Any lesion that causes compression or transsection of sensorimotor spinal tracts can lead to fecal incontinence. Incontinence may be permanent, especially with severe lesions of the sacral segments. Other signs and symptoms reflect motor and sensory disturbances below the level of the lesion, such as urinary incontinence, weakness or paralysis, paresthesia, analgesia, and thermanesthesia.

♦ Stroke. Temporary fecal incontinence occasionally occurs in a stroke patient but usually disappears when muscle tone and DTRs are restored. Persistent fecal incontinence may reflect extensive neurologic damage. Other findings depend on the location and extent of damage and may include urinary incontinence, hemiplegia, dysarthria, aphasia, sensory losses, reflex changes, and visual field deficits. Typical generalized signs and symptoms include headache, vomiting, nuchal rigidity, fever, disorientation, mental impairment, seizures, and coma.

♦ Tabes dorsalis. This late sign of syphilis occasionally results in fecal incontinence. It also produces urinary incontinence, ataxic gait, paresthesia, loss of DTRs and temperature sensation, severe flashing pain, Charcot’s joints, Argyll Robertson pupils, and possibly impotence.

OTHER CAUSES

♦ Drugs. Chronic laxative abuse may cause insensitivity to a fecal mass or loss of the colonic defecation reflex.

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

Maintain proper hygienic care, including control of foul odors. Also, provide emotional support for the patient because he may feel deep embarrassment. For the patient with intermittent or temporary fecal incontinence, encourage Kegel exercises to strengthen abdominal and perirectal muscles. (See How to do Kegel exercises, page 232.) For the neurologically capable patient with chronic incontinence, provide bowel retraining. (See Bowel retraining tips.)

PEDIATRIC POINTERS

Fecal incontinence is normal in infants and may occur temporarily in young children who experience stress-related psychological regression or a physical illness associated with diarrhea. Pediatric fecal incontinence can also result from myelomeningocele.

GERIATRIC POINTERS

Fecal incontinence is an important factor when long-term care is considered for an elderly patient. Leakage of liquid fecal material is especially common in males. Age-related changes affecting smooth-muscle cells of the colon may change GI motility and lead to fecal incontinence. Before age is determined to be the cause, however, any pathology must be ruled out.

Fetor hepaticus

Fetor hepaticus—a distinctive musty, sweet breath odor—characterizes hepatic encephalopathy, a life-threatening complication of severe liver disease. The odor results from the damaged liver’s inability to metabolize and detoxify mercaptans produced by bacterial degradation of methionine, a sulfurous amino acid. These substances circulate in the blood, are expelled by the lungs, and flavor the breath.

If you detect fetor hepaticus, quickly determine the patient’s level of consciousness. If he’s comatose, evaluate his respiratory status. Prepare to intubate him and provide ventilatory support if necessary. Start a peripheral I.V. catheter for fluid administration, begin cardiac monitoring, and insert an indwelling urinary catheter to monitor output. Obtain arterial and venous samples for analysis of blood gases, ammonia, and electrolytes.

If you detect fetor hepaticus, quickly determine the patient’s level of consciousness. If he’s comatose, evaluate his respiratory status. Prepare to intubate him and provide ventilatory support if necessary. Start a peripheral I.V. catheter for fluid administration, begin cardiac monitoring, and insert an indwelling urinary catheter to monitor output. Obtain arterial and venous samples for analysis of blood gases, ammonia, and electrolytes.HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

If the patient is conscious, closely observe him for signs of impending coma. Evaluate deep tendon reflexes, and test for asterixis and Babinski’s reflex. Be alert for signs of GI bleeding and shock, common complications of end-stage liver failure. Also, watch for increased anxiety, restlessness, tachycardia, tachypnea, hypotension, oliguria, hematemesis, melena, or cool, moist, pale skin. Place the patient in a supine position with the head of the bed at 30 degrees. Administer oxygen if necessary, and determine the patient’s need for I.V. fluids for albumin replacement. Draw blood samples for liver function tests, serum electrolyte levels, hepatitis panel, blood alcohol count, a complete blood count, typing and crossmatching, a clotting profile, and ammonia level. Intubation, ventilation, or cardiopulmonary resuscitation may be necessary. Evaluate the degree of jaundice and abdominal distention, and palpate the liver to assess the degree of enlargement.

Obtain a complete medical history, relying on the patient’s family if necessary. Focus on any factors that may have precipitated liver disease or coma, such as a recent severe infection; overuse of sedatives, analgesics, (especially acetaminophen), alcohol, or diuretics; excessive protein intake; or recent blood transfusion, surgery, or GI bleeding.

MEDICAL CAUSES

♦ Hepatic encephalopathy. Fetor hepaticus usually occurs in the final, comatose stage of this disorder but it may occur earlier. Tremors progress to asterixis in the impending stage, which is also marked by lethargy, aberrant behavior, and apraxia. Hyperventilation and stupor mark the stuporous stage, during which the patient acts agitated when aroused. Seizures and coma herald the final stage, along with decreased pulse and respiratory rates, positive Babinski’s reflex, hyperactive reflexes, decerebrate posture, and opisthotonos.

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

Effective treatment of hepatic encephalopathy reduces blood ammonia levels by eliminating ammonia from the GI tract. You may have to administer neomycin or lactulose to suppress bacterial production of ammonia, give sorbitol solution to induce osmotic diarrhea, give potassium supplements to correct alkalosis, provide continuous gastric aspiration of blood, or

maintain the patient on a low-protein diet. If these methods prove unsuccessful, hemodialysis or exchange transfusions may be performed.

maintain the patient on a low-protein diet. If these methods prove unsuccessful, hemodialysis or exchange transfusions may be performed.

During treatment, closely monitor the patient’s level of consciousness, intake and output, and fluid and electrolyte balance.

PEDIATRIC POINTERS

A child who is slipping into a hepatic coma may cry, be disobedient, or become preoccupied with an activity.

GERIATRIC POINTERS

Along with fetor hepaticus, elderly patients with hepatic encephalopathy may exhibit disturbances of awareness and mentation, such as forgetfulness and confusion.

PATIENT COUNSELING

Advise the patient to restrict his intake of dietary protein to as little as 40 g/day. Recommend that he eat vegetable protein rather than animal protein sources. Inform the patient that medications used to treat and prevent hepatic encephalopathy do so by causing diarrhea, so he shouldn’t stop taking the drug when diarrhea occurs.

Fever

[Pyrexia]

Fever is a common sign that can arise from numerous disorders. Because these disorders can affect virtually any body system, fever in the absence of other signs usually has little diagnostic significance. A persistent high fever, though, represents an emergency.

Fever can be classified as low (oral reading of 99° to 100.4° F [37.2° to 38° C]), moderate (100.5° to 104° F [38.1° to 40° C]), or high (above 104° F). Fever over 106° F (41.1° C) causes unconsciousness and, if sustained, leads to permanent brain damage.

Fever may also be classified as remittent, intermittent, sustained, relapsing, or undulant. Remittent fever, the most common type, is characterized by daily temperature fluctuations above the normal range. Intermittent fever is marked by a daily temperature drop into the normal range and then a rise back to above normal. An intermittent fever that fluctuates widely, typically producing chills and sweating, is called hectic (or septic) fever. Sustained fever involves persistent temperature elevation with little fluctuation. Relapsing fever consists of alternating feverish and afebrile periods. Undulant fever refers to a gradual increase in temperature that stays high for a few days and then decreases gradually.

Fever can be either brief (less than 3 weeks) or prolonged. Prolonged fevers include fever of unknown origin, a classification used when careful examination fails to detect an underlying cause.

If you detect a fever higher than 106° F (41.1° C), take the patient’s other vital signs and determine his level of consciousness (LOC). Administer an antipyretic and begin rapid cooling measures: Apply ice packs to the axillae and groin, give tepid sponge baths, or apply a cooling blanket. These methods may evoke a cooling response; to prevent this, constantly monitor the patient’s rectal temperature.

If you detect a fever higher than 106° F (41.1° C), take the patient’s other vital signs and determine his level of consciousness (LOC). Administer an antipyretic and begin rapid cooling measures: Apply ice packs to the axillae and groin, give tepid sponge baths, or apply a cooling blanket. These methods may evoke a cooling response; to prevent this, constantly monitor the patient’s rectal temperature.Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree