Mosaic from the island of Kos.

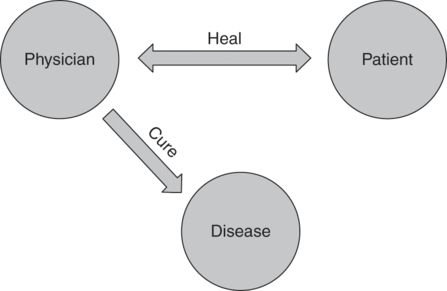

Table 7.1 shows some of the contrasts between healing and curing, from both the patient’s perspective and the physician’s perspective.26 It starts with the contrast between curing and healing. Curing is an attempt to control or eradicate a disease for which the energy primarily comes from the practitioner and the medical system.27 Healing is a move toward a greater sense of integrity or wholeness (whether or not the disease is cured), for which the energy primarily comes from the patient.28 Still, the physician has a crucial role in supporting or facilitating this transformative healing process.29 The table demonstrates that each characteristic that is important for curing is contrasted with a diametrically opposed process that is important for healing. This contrast is very real, and these truly are diametrically opposed processes. One cannot be replaced by the other, but they do synergize and reinforce each other. For instance, the more competence and knowledge a physician possesses in curing disease, the more open the patient is likely to be in relating to the physician in a way that facilitates healing. By contrast, the more effective the physician is in relating to the patient as a person, the more likely he or she is to join the physician in curing the disease by following advice, taking medications as prescribed, and so on. Medicine is a complicated and challenging job in which we are asked to do two diametrically opposed and synergizing jobs at the same time – a process we call whole person care.30 How do we support the formation of a medical professional who is able to do what Scott Fitzgerald said was the test of a first-rate intelligence – “the ability to hold two opposed ideas in mind at the same time and still function”?31

| Hippocratic | Asklepian | |

|---|---|---|

| Patient | ||

| Problem | Symptoms or dysfunction | Suffering |

| Possibility | Being cured | Healing |

| Action | Holding on | Letting go |

| Goal | Survival | Growth |

| Self-image | At the effect of disease | Responsible for coping with illness |

| Doctor | ||

| Focus | Disease | Person with illness |

| Communication | Content | Relationship |

| Digital | Analog | |

| Conscious | Unconscious | |

| Power | Power differential | Power sharing |

| Presence | Competent technician | Wounded healer |

| Epistemology | Scientific | Artistic |

| Management | Standardized | Individualized |

| Effect | Real | “Placebo” |

Mindfulness

Although a great deal of attention has been given to reflective practice in the medical literature, most of the published studies have focused primarily on the cognitive components of reflection – how to train practitioners to think and do differently and better.32 We would suggest that a deeper focus for reflection should be on the being or presence of the practitioner that provides the ground for his or her thoughts and actions. Mindfulness has been described by Kabat-Zinn as the awareness that arises from paying attention moment to moment nonjudgmentally.33 This is the kind of awareness that physicians require to provide the deep presence that is necessary to promote relationships, real change, and problem resolution.20 Mindfulness as a practice that focuses on being present was first introduced to the medical literature by Epstein34 and is now recognized as a form of reflective practice.35 There is evidence that mindfulness practice improves the well-being of practitioners36 and that mindfulness itself improves quality and patient satisfaction in the clinical encounter.37 It is also the type of awareness that will allow physicians to encompass simultaneously the two aspects of medicine,24 the curing face and the healing face. The caduceus is used as a metaphor, with the white snake representing curing and the black snake representing healing to symbolize this process to our students (see Figure 7.3).26

The story goes that one day the god Hermes came upon two warring serpents.38 He thrust his staff between them, separating them and preventing either snake from overcoming the other, but maintaining them in a balance and tension between opposing forces. This represents the balance and tension between curing and healing in medicine. And what does the staff between the two snakes represent? The staff represents the mindful physician whose ability to be fully present allows him to identify, not with curing and not with healing, but with what is emerging in the moment-to-moment interaction with the patient. This sounds like a difficult task but it is exactly what we have experienced in our own practices. When faced with a difficult problem, we have found that what works best is not favoring the curing agenda or the healing agenda, but being open to both, focusing on moment-to-moment engagement with the patient. An example of this process in a young woman contemplating discontinuation of her dialysis treatment for her chronic renal failure is described in detail elsewhere.30

Congruent presence

Since it is improving their presence in their relationship with patients that is the primary goal in the professional identities we wish to see develop in our students, we also provide students with a simple structure to frame these relationships. The concept of congruence, derived from the work of Virginia Satir,39 is used to clarify for the students the kind of relationships we are seeking to promote.

Every interaction with another person involves self, other, and context.25 Satir identifies four common stances (placating, blaming, super-reasonable, irrelevant) that involve leaving out a part or parts of the interaction.40,25 The stances facilitate students’ awareness of how they are relating in different contexts. For instance, in role plays of interactions with patients or colleagues, students may become aware that they adopt a placating stance, or a super-reasonable stance, without any conscious decision. None of these stances are bad, but students can easily sense how placating or blaming limits the interaction and may lead to a lack of satisfaction in both parties or even to outright conflict. Once a stance is brought to awareness, the student has a choice – to stay in that stance or put back the missing part(s). Being aware and present for all parts in an interaction is what Satir would call congruent.39 Students are encouraged to seek congruence in all of their relationships because this is central to the kind of professional identity formation we wish to promote – that of the competent clinician who is also a healer.

Interestingly, the mindful awareness that allows one to be present for both curing and healing is the same awareness that allows one to be congruent in our clinical interactions – present to ourselves, the patient, and the clinical context. Clinical congruence is a learned skill that takes all of our human capabilities and also requires us to address an obstacle that is very powerful in the medical context – death anxiety.

Death anxiety and professional identity formation

One self-evident aspect of medicine is that our patients die. Even with the best possible care, they die, and when they don’t die, we fear (and know) that they will. Solomon et al.41 have shown in numerous experiments that anything that makes us aware of our own mortality triggers defenses that shield us from the terror that thoughts of our own death involve – terror management theory.42 Such triggers can be anything from passing by a funeral parlor to answering a questionnaire that mentions death. We in medicine live in a world bombarded by such triggers.

What defenses would we expect to see activated and how might they be expected to affect our professional practice? According to Pyszczynski et al.,42 the first or proximal defenses consist in suppressing the information and attendant anxiety. This explains why most people, including physicians, deny that they think a lot about their own mortality. These proximal defenses are not very effective and the psyche seeks a more powerful solution to the problem – the distal defenses. Awareness of our own mortality (that we could disappear tomorrow, virtually without trace) is a severe blow to our self-esteem. The distal defenses drive us to bolster our self-esteem by associating with a group with whom we have some connection. Presumably, we feel better about ourselves if a group who shares our values will survive, even if we ourselves may die. More problematically, we distance ourselves from groups who do not share our values – those we consider “other.” These researchers have demonstrated multiple examples of this phenomenon in controlled experiments, whether the group identities are associated with religion, ethnic origin, social class, or other factors.43 We, and others, have posited that medical professional identity can function in exactly the same way. And the group considered “other” in this context may be patients.41

Controlled experiments to demonstrate this phenomenon in medicine do not yet exist (though such research would be very important), but we believe that we see this phenomenon frequently in our clinical practice. It is at the heart of why doctors tend to distance themselves from their patients and of why they tend to focus more on the curing than on the healing aspects of medicine. In a curing mode, my skills and knowledge are what distinguish me from my patients and make them appear as other. They are dying but they are not part of my group. On the other hand, in the healing mode, I need to adopt the wounded healer role (the patient and I are brothers), and no such distancing or “othering” will work.44

How can we envisage ways to deal with this inherent aspect of medical practice and avoid turning medical professional identity formation into a means of bolstering our own self esteem by distancing ourselves from our patients? There is no quick answer to this problem, but the solution probably lies in deliberately bringing death anxiety to consciousness. This is supported by a long tradition in Buddhist meditation in which bringing one’s own mortality to consciousness is a powerful path to mindfulness.45 We also believe that there is a lesson to be learned from the experience of the palliative care and hospice movement.46

Reflection on experiential learning, reflection, and identity formation

How does the focus on mindfulness and congruence fit with our previous discussion of experiential learning and reflection and with what we see as priorities in medical professional identity formation? It is important to realize that our task will never be to focus on healing at the expense of curing, or thinking and doing at the expense of being. However, we do see a gradation in terms of order and depth. Perhaps the best analogy is Satir’s iceberg metaphor,47 with actions clearly visible at the top, and deeper levels of the psyche such as thoughts, feelings, expectations, and powerful longings and yearnings at progressively lower levels. The key aspect of this vertical perspective is to realize that lower levels provide the energy for higher levels. Most of us have had the experience of the ease with which we are motivated to think and to act when we are passionate about an endeavor.48 We want, as far as possible, to nurture students’ passion for medicine, which is why our priority in both experiential learning and the reflection based on it is to put students in deep touch with why they are pursuing a medical career and what they hope to bring to their work. Our experience is that most students are very much in touch with what might be called their deepest yearnings to make contact with and make a profound difference in the lives of their patients early in their careers, and that this can become eroded as their professional identity develops. So, we see that the highest priority in experiential learning and reflection is to keep students deeply in touch with themselves and their deepest motivations.

In an excellent article on reflection and phronesis, Kinsella49 identifies four kinds of reflection, which she names: receptive reflection; intentional reflection; embodied reflection; and reflexivity. She sees them respectively as relating to being, thinking, doing, and deconstructing and becoming. The correspondence of the first three to our categories of reflective presence, reflective thinking, and reflective doing is very clear. We see reflective presence as being primary and feeding into the other two. This is why we put such a high value on mindfulness as a way of helping students deal with distractions, preoccupations, and their own reactivity so that they can make deep contact with themselves and with their patients in the service of both curing and healing. This also fits with Satir’s model of congruence, in which the motor force for being congruent (fully present to self, others, and context) is being in touch with deep levels of our personal icebergs, and in particular, our yearnings and longings.7

What about the fourth kind of reflection that Kinsella calls reflexivity? We see this form of reflection as very relevant to medicine and to professional identity formation as a sociocultural phenomenon in which students are changed by, and participate, in an ongoing sociocultural change in medicine and society.13 It is important that students become aware of the sociocultural realities that surround them in medicine and society and are able to reflect on and respond to their environment in a broad sense – reflexivity. We do not see students as only passive recipients in the process; in addition, they are agents capable of not only accepting and participating in the norms of their environment but also of “resisting” when their deepest values are threatened. In fact, as Shem and Bergman point out, resisting may be the most important act of medical students and residents to maintain their integrity and professional identity in a medical environment that is too often uncaring and dehumanized.50 We believe that the real hope of medicine lies not in passing on current medical practices and attitudes to students as they become doctors, but in promoting a new kind of professional identity in our students that sees deep connection as the highest priority in their own lives and in their relationships with patients.

Pedagogic strategies

Orientation

In the section that follows, we illustrate some of the ways we use experiential learning and reflection to promote mindful congruence in a clinical context. All of the sessions involve reflection on the part of students, although, as Kinsella points out,49 it is impossible to completely separate the four kinds of reflection, particularly in a live session. We attempt to keep in mind the words of T.S. Eliot from his Choruses from “The Rock.”51

Where is the wisdom we have lost in knowledge?

We follow the order suggested by Eliot, first to attempt to provide students with a powerful experience, then to tap their own and others’ wisdom, and only as necessary to aid in those primary purposes to impart a cognitive framework (knowledge) and relevant supporting data (information). We believe that this is likely to have a long-term impact on our students.

Lectures

Because of the way McGill’s curriculum is organized, lectures occur primarily in the first year. We seek to use our lectures to harness the students’ optimism and enthusiasm in the service of a professional identity that emphasizes mindful congruence in relating to patients and commitment to both technical excellence and the facilitation of healing. Part of this is clarifying some of the cognitive frames through which we see medicine. However, lectures are also a good way of touching students’ emotions, getting them engaged both cognitively and at a deeper level, and inspiring them to put their whole selves into their development as doctors.

To have this kind of effect, lectures need to become experiential, and we concur with Heath and Heath on ways to do this.52 Their formulation of what makes teaching effective is useful. All of our teaching sessions have the following four elements: Surprise; Engagement; Emotional involvement; Stories. Let us briefly examine each of these in turn.

Surprise. Most students arrive at lectures carrying with them whatever happened earlier in the day, concerned about what more they need to do before their day is complete, with an overriding attitude of “business as usual.” It is how most of us live most of our lives. It takes something unexpected to get us and them out of this mode. We attempt to use the material we are presenting to give students a surprise early in our lectures. This might be a short story with a surprising ending, an interactive exercise that raises their awareness, or anything else within the topic to be discussed that gets their attention because it is unexpected. This requires creativity on the part of the lecturer, but it is surprisingly easy once mastered and part of the joy and (for us) duty of a medical teacher.

Engagement. The objective is to get the students to work with the lecturer. There are several techniques: posing questions to the class, getting them to talk with each other about a topic before answers are provided, and frequently asking for comments and questions to which the lecturer then responds. The class should become a conversation, not a monologue. It may include doing role plays in front of the class with students playing the roles. One of the factors that we have found interferes with engagement is students who spend the whole class on their laptops or phones. We have been unwilling to outlaw this practice but have found that simply requesting that students close their electronic devices is remarkably effective.

Emotional involvement and Stories. We have found these two elements to be the most important factors in making our lectures experiential and effective. They are discussed together because it is difficult to involve students emotionally without stories, and stories have the additional benefit of tying a lecture together and making it memorable.52 We have used performed stories in the form of movies or passages from books, but, in our experience, the most effective stories are personally experienced and emotionally charged clinical experiences that put the student in a patient’s or physician’s shoes. If possible, we like to have a single major story that is introduced early on and returned to for further elaboration at intervals and at the end of the lecture. For us, the success of a lecture depends more than anything on our ability to find a suitable and powerful story to involve our students emotionally and illustrate the points we are trying to get across.

Panel discussions

One effective way that we have found to engage in reflection and retain students’ attention and engagement, to involve them emotionally, and to teach effectively about the impact of medical care on patients and on practitioners, are panel discussions in which patients or physicians respond to questions about their own experience.

We run these sessions with three or four panel members who consist of either patients or physicians (we usually do not mix them). We attempt to pick participants with very different experiences and backgrounds. The panel is chaired by one of us who poses the questions, reflects on the answers if appropriate, and keeps the discussion on track so that the lessons emerging are highlighted. The questions that we pose are very straightforward, focusing on a brief resumé of the person’s background and story, their worst experience, their best experience, and what they learned that they wish they had known earlier or would like to pass on. It is extraordinary how effectively and movingly both patients and physicians respond to these questions. These are not questions that students normally get to ask their patients in clinical care or to pose to their mentors. For both patients and physicians, the stories and experiences they remember most vividly almost exclusively concern the relationship between patient and doctor at a human rather than technical level. In our experience, patients do remember clinical mistakes, but they primarily focus on the attitude and response of the physician(s) involved.

Often, the issue is primarily one of attitude and communication. A woman in her 50s who had been diagnosed with ovarian cancer recalled asking her doctor after the operation to remove the tumor, “Tell me whether I will survive with this disease.” His response as he left the room was to say, “Ask me again in two years.” She was devastated and said she spent the next two years in a state of limbo waiting for the tumor to return. It did not recur, and now, ten years later, she was doing well. She praised her doctor for his wonderful care in every other way, but the words he used that day would never be forgotten.53 Doctors have their own failures in relationships that may stay with them for a lifetime. A senior medical subspecialist recalled that many decades ago, when he was beginning his medical practice, he had been caring for a young man with a serious but treatable disease. As it became evident that the treatments were not working and the patient was deteriorating and probably beginning the dying process, our colleague stopped visiting. He felt he did not know what to say but realized in retrospect (and to some extent at the time) that his presence could have been very important to the patient. He recounted this failure (rather than cognitive or technical failures) as the worst experience in his long and productive career. There are many other such stories that touch the students deeply and help them reflect on the values that are fundamental to medical practice. Teaching students about such values didactically is important, but hearing authentic accounts of how patients and physicians experience these values in clinical care has more impact and is likely to have a more lasting effect.

Patients and physicians also very vividly remember the good things that were done. Patients remember the doctor who took the extra time to explain a problem in detail or to reassure them; doctors remember the times they went beyond the call of duty or usual practice for a particular patient and how rewarding that was for the doctor himself or herself. Students find these sessions very motivating and inspiring. There are always many questions to the participants, and our main challenge is to bring these sessions to a close in the face of students’ overwhelming curiosity and enthusiasm.

A small-group course on mindful medical practice

Despite the impactful nature of our simulation sessions described later, we realize that students may require a more prolonged exposure to these ideas and experiences to have a long-term effect. For this reason, a seven-week small-group core course aimed at helping students to be mindfully congruent in a clinical context was designed.54 Each class includes an experiential element, an opportunity to reflect, and a clear cognitive message. The process involves brief periods of guided awareness, narrative exercises, simple role plays, dyadic sharing, and group reflection and discussion. Topics of individual classes include medical mistakes, resilience, being present to suffering and death, and challenging interviews. The aim is to prepare students for the intense clerkship experience with awareness and skills that will help them to be both more resilient and more effective in their clinical work.55

Essays and whole class reflection

The most significant influence on students’ professional identity formation is probably not the pre-clinical teaching in the first two years, but the intense experience in the third- and fourth-year clerkships. As evidenced by a change in students’ attitudes and values during this period, not all of the clinical exposure is supportive of the desired professional identity. To get students to reflect on their clinical experience, and at the same time to turn back the clock to their values and views before clerkship, they are asked to write an essay on a topic related to healing. To pass the course, each student must write an essay that addresses a variety of topics relating to healing that can be summarized as “Experience of the healer role at its best” or “Experience of the healer role at its worst.”

Part of the benefit is in the students’ reflective process in writing the essay and receiving faculty feedback. A second aspect of the learning process is that these essays are used in a recall day in which selected essays are discussed with the entire medical class. Three or four essays (including the winning essay) are selected to be read in front of the whole class. A facilitated discussion takes place that includes the students and a panel of four faculty members, each of whom are assigned a specific role in their review and reflection. The roles assigned vary slightly depending on faculty participants, but usually include the following: Dr. Healing, Dr. Ethics, Dr. Professionalism, and Dr. Physicianship. Despite the artificiality of these assignments, it has been found that the resulting multifaceted discussions that include active student participation are extremely rich and powerful. Students are interested to hear the essays of their classmates, and the essays that are chosen have proved to be excellent, provocative, and illuminating. Students appreciate a day out of their busy clinical work to reflect on their personal experience and those of their peers. We find that whatever the specifics of the essays chosen for review, there is enough common in the students’ experience that they can easily relate their own experience to that recounted. The subsequent discussion allows for broadening and deepening of their reflection.

Simulation

One of the more powerful experiential strategies in promoting reflection and professional identity formation is simulation of clinical interactions, with trained actors playing the role of patients or professional colleagues. Such simulation is used at McGill to train students in taking histories and communicating, dealing with professional conflict, and being congruent and resilient in difficult and potentially abusive interactions with professional superiors and patients.54 Although these are different sessions, some occurring in second year (before clerkship) and others in third year and fourth year (during clerkship), they share a fairly similar pattern and an overarching objective of training students in how to best relate to others in a clinical context.

The sessions that are most clearly aimed at professional identity formation are conducted in third year in groups of thirty students. They are entitled The Physician as Healer: Resilient Responses to Difficult Clinical Interactions. We have described these sessions in more detail elsewhere.54 The key component is that each student participates for five minutes in a deliberately stressful clinical interaction that is then debriefed with a faculty member and the two other students in his or her group of three who have observed the interaction through a one-way mirror. Every student participates in one interaction and observes two interactions. The learning and reflection is organized in three parts: reflection in action during the scenario itself; reflection on action during the small-group debrief; and further reflection for action and the opportunity to share learning between all thirty students and all ten faculty during a large-group debrief. The other parts of the day, consisting of a pre-brief and a faculty debrief, are designed to ensure that faculty and students are well prepared and clear about the objectives of the session, and that faculty have an opportunity at the end of the day to suggest possible modifications and to communicate any concerns they have about the well-being of any students.

These simulation sessions are very powerful. We deliberately push students out of their comfort zone, something that is essential if any deep experiential learning is to occur.56 Students vary widely in their instinctive reactions, and we use the small- and large-group debriefs to help them to hold a mirror to themselves and to see alternative ways of responding. The overall objective of these sessions is to encourage mindful congruence in clinical interactions, but rather than teach them didactically, we use the students’ experience in the sessions as the basis for reflection.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree