Chapter 5 Ethnobotany and ethnopharmacy

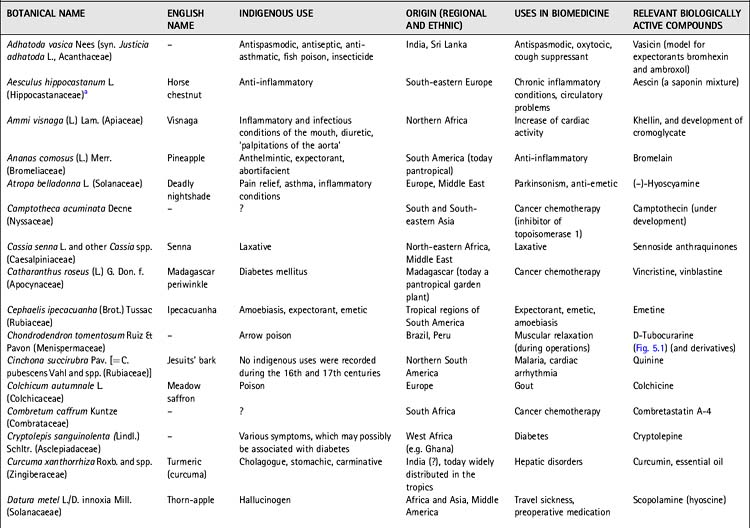

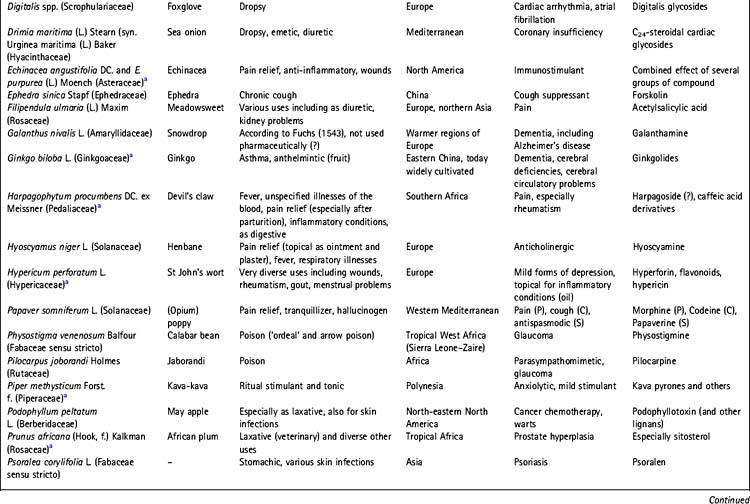

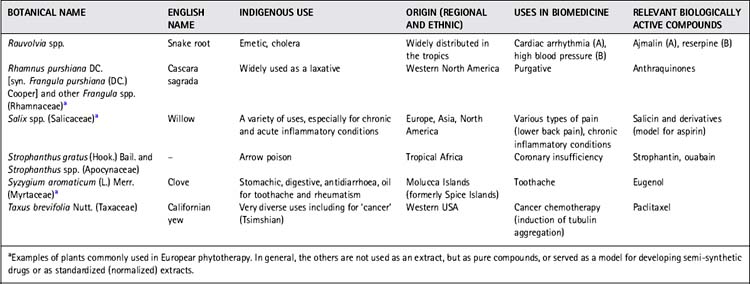

Many drugs that are commonly used today (e.g. aspirin, ephedrine, ergometrine, tubocurarine, digoxin, reserpine, atropine) came into use through the study of indigenous (including European) remedies – that is, through the bioscientific investigation of plants used by people throughout the world. Table 5.1 lists just a few of the many examples of drugs derived from plants. As can be seen, most plant-derived pharmaceuticals and phytomedicines currently in use were (and often still are) used by native people around the world. Accordingly, our information is derived from local knowledge as it was and is practised throughout the world, although European and Mediterranean traditions have had a particular impact on these developments. The historical development of this knowledge is discussed in Chapter 2. This chapter is devoted to traditions as old as, or older than the written records but which have been passed on orally from one generation to the next. Some of this information, however, may have not been documented in codices or studied scientifically until very recently.

Table 5.1 Botanical drugs used in indigenous medicine and of importance in the development of modern drugs

Ethnobotany

This broad definition is still used today, but modern ethnobotanists face a multitude of other tasks and challenges (see below). Medicinal plants have always been one of the main research interests of ethnobotany and the study of these resources has also made significant contributions to the theoretical development of the field (Berlin 1992); however, the more anthropologically oriented fields of research are beyond the scope of this introductory chapter.

Ethnopharmacology

Ethnopharmacology as a specifically designated field of research has had a relatively short history. The term was first used in 1967 in the title of a book on hallucinogens (see Efron et al 1970). The field is nowadays much more broadly defined.

The observation, identification, description and experimental investigation of the ingredients, and of the effects of the ingredients, and the effects of such indigenous drugs, is a truly interdisciplinary field of research which is very important in the study of traditional medicine. Ethnopharmacology is here defined as ‘the interdisciplinary scientific exploration of biologically active agents traditionally employed or observed by man’ (Bruhn & Holmstedt 1981: 405–406).

The story of curare

An interesting example of an early ethnopharmacological approach is provided by the study of the botanical origin of the arrow poison curare, its physiological effects and the compound responsible for these effects. Curare was used by certain, wild, tribes in South America for poisoning their arrows and many early explorers documented this usage. The historical aspects of the scientific investigation of curare by Bernard (1966) are outlined in Chapter 2, but the detailed descriptions made by Alexander von Humboldt in 1800, of the process used to prepare poisoned arrows in Esmeralda on the Orinoco River, are equally interesting. von Humboldt had met a group of native people who were celebrating their return from an expedition to gather the raw material for making the poison and he described the ‘chemical laboratory’ used to prepare the poison (Humboldt 1997:88, from the original text published 1800):

The botanical source of curare was eventually identified as the climbing vine Chondrodendron tomentosum Ruiz and Pavón; other species of the Menispermaceae (Curarea spp. and Abuta spp.) and Loganiaceae (Strychnos spp.) are also used in the production of curares of varying types (Bisset 1991). von Humboldt then eloquently described one of the classical problems of ethnopharmacology:

Ethnopharmacology and the convention on biological diversity (convention of RIO)

None of the studies discussed so far took the benefits for the providers (the states and their people) into account. This has changed in recent years. Ethnopharmacological and related research using the biological resources of a country are today based on agreements and permits, which in turn are based on international and bilateral treaties. The most important of these is the Convention of Rio or the Convention on Biological Diversity (see http://www.biodiv.org/chm/conv.htm), which looks in particular at the rights and responsibilities associated with biodiversity on an international level:

The basic principles of access are regulated in article 5:

The rights of indigenous peoples and other keepers of local knowledge are addressed in article 8j:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree