5 Ethics, preoperative considerations, anaesthesia and analgesia

Ethical and legal principles for surgical patients

The level of trust invested in surgeons by patients when they submit to a surgical procedure is unique in society, as is the potential for harm and exploitation. It is paramount therefore that the practice of surgery is subject to ethical and legal principles that enshrine the rights of patients and the duties of surgeons within the context of varying societal expectations. Medical ethics is a complex area, particularly with the challenges that advances in bioethics and new technologies bring, and there should be sufficient latitude within the framework of medical ethics to accommodate differing views in resolving ethical dilemmas. In the United Kingdom, ethical standards are upheld by regulatory bodies such as the General Medical Council and the Surgical Royal Colleges (Table 5.1).

Table 5.1 The duties of a doctor registered with the General Medical Council

| Patients must be able to trust doctors with their lives and health. To justify that trust you must show respect for human life and you must: | |

| Make the care of your patient your first concern | |

| Protect and promote the health of patients and the public | |

| Provide a good standard of practice and care | Keep your professional knowledge and skills up-to-date |

| Recognize and work within the limits of your competence | |

| Work with colleagues in the ways that best serve patients’ interests | |

| Treat patients as individuals and respect their dignity | Treat patients politely and considerately |

| Respect patients’ right to confidentiality | |

| Work in partnership with patients | Listen to patients and respond to their concerns and preferences |

| Give patients the information they want or need in a way they can understand | |

| Respect patients’ right to reach decisions with you about their treatment and care | |

| Support patients in caring for themselves to improve and maintain their health | |

| Be honest and open and act with integrity | Act without delay if you have good reason to believe that you or a colleague may be putting patients at risk |

| Never discriminate unfairly against patients or colleagues | |

| Never abuse your patients’ trust in you or the public’s trust in the profession | |

| You are personally accountable for your professional practice and must always be prepared to justify your decisions and actions. | |

Principles in surgical ethics

Principalism

Principalism is a widely adopted approach to medical ethics. Championed by Beauchamp and Childress, it judges all possible actions in a particular ethical dilemma against four principles. These are autonomy, beneficence, non-malfeasance and justice (Summary Box 5.1). Each is considered in more detail below and while addressed separately, it becomes apparent that the principles are linked and do not simply cover four unrelated issues. Protagonists of this approach to bioethics suggest that it provides a practical framework for working through ethical dilemmas, allowing identification of important issues and is universally applicable with its four principles widely acceptable irrespective of culture or religious beliefs. The principles can be applied to most surgical clinical scenarios and if each element is given due consideration it is unlikely that the resulting decision will be unethical.

Informed consent

General considerations

Capacity exists if a patient can:

• understand and retain the information presented

• weigh up the implications, including risk and benefit of the options

Circumstances where the capacity to consent may not exist:

• is suitably trained and qualified

• has sufficient knowledge of the proposed procedure including risks

• understands the process of consent (in the UK as laid out by the GMC).

Consent in specific circumstances

Confidentiality

See Table 5.2 for important sources of information regarding ethics in medicine.

Table 5.2 Sources of further information on ethics

Specific topics

Ethics committees

Research on human subjects is necessary to advance medical knowledge and treatment. Ensuring that it is carried out in a safe and ethical way is the remit of the ethics committee. The Declaration of Helsinki sets out the principles of ethical research. All clinical trials involving human subjects or tissue must receive ethical approval prior to commencing recruitment. For information on how ethical approval is obtained in the UK see the National Research Ethics Service which is part of the National Patient Safety Agency (http://www.nres.npsa.nhs.uk/). The composition of ethics committees is important and should reflect societal diversity in terms of age, gender, ethnicity and disability and embody a broad range of experience and expertise so that the scientific, clinical and methodological aspects of a research proposal can be reconciled with the welfare of the research participants.

Preoperative assessment

Assessment of operative fitness and perioperative risk

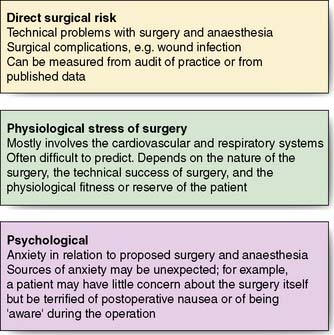

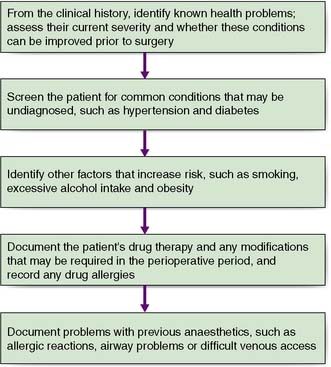

The first priority is to establish the severity and extent of the condition requiring surgery by employing appropriate imaging and other investigations. For example, it is important to know that both recurrent laryngeal nerves are functional prior to thyroid surgery as damage is a recognized complication of this type of operation, on the other hand malignant conditions require appropriate staging to establish the disease extent. The second objective is to identify co-morbid conditions through careful clinical assessment and through optimization, minimize perioperative risk. Figure 5.1 details the areas of potential perioperative risk and Figure 5.2 shows a logical sequence of preoperative assessment. Details of previous operations and anaesthetics should be sought, as well as drug, alcohol and smoking history, specific allergies and concerns. Investigations to assess the surgical condition, co-morbid conditions and general health should be arranged as soon as possible to minimize surgical delay. Thorough and timely preoperative assessment is essential to avoid the expense and delay of cancelled or delayed surgery. Good quality assessment and appropriate optimizations prior to admission mean that many patients can be admitted on the day of surgery.

Systematic preoperative assessment

Smoking

All patients should be offered support to quit smoking, particularly once the decision to operate has been made. The benefits of preoperative smoking cessation are listed in Table 5.3 and should be explained to the patient. Some of the benefits occur within hours (reduced circulating nicotine and carboxyhaemoglobin) while others take weeks, months, or even years. Despite the significant advantages in the perioperative period, many patients are unable or unwilling to stop smoking prior to and after their surgery. Referral to specialist services that support patients to stop smoking may help.

Table 5.3 Benefits of preoperative smoking cessation

Obesity

Obese patients are at increased risk from surgery and anaesthesia and special equipment may be required. Obese patients are at risk of major associated co-morbidities (e.g. diabetes, obstructive sleep apnoea, degenerative joint disease and cardiovascular disease). Table 5.4 details some of the technical difficulties, perioperative risks and comorbid conditions associated with obesity. If the risks of surgery are outweighed by its potential benefits, surgery may be postponed. In practice, the majority of patients cannot lose weight without support and referral to the GP and dietician for weight loss programmes, including supervised exercise, may be beneficial.

Table 5.4 Significance of obesity in the perioperative period

| Cardiovascular system |

| Respiratory system |

| Surgical |

| Other |

Drug therapy

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree