http://evolve.elsevier.com/Edmunds/NP/

Up to half of all patients with serious chronic illnesses do not take their medication as prescribed and thus fail to derive the expected benefits (Turnbough & Wilson, 2007). How can this finding be true? Whose responsibility is it when patients fail to comply? What role does the provider play in helping the patient implement the therapeutic regimen or in impeding the process? How can health care providers seek to change this statistic?

Reports by researchers (Funnell, 2003; Mitchell & Selmes, 2007) on why patients do not take their medications as instructed concluded the following:

Although the health care practices of medicine, nursing, pharmacy, and other related disciplines rest on a scientific foundation, how scientific principles are introduced in the relationship with the patient has everything to do with therapeutic success. Spoken of as the “art” of care, substantial evidence suggests that this component of health care is equally as important as the “science” of health care. This dimension of care is behind the admonitions to “treat the patient, not the laboratory numbers” and to “individualize therapy.”

The therapeutic experiment is a term that has been in vogue in schools of pharmacy for a number of years. The concept of a therapeutic experiment suggests that to have rational use of drug therapy (which implicitly means the right drug, to the right patient, at the right time, in the proper dosage, by the appropriate route of administration, for the right problem), a therapeutic process must take place.

However, the therapeutic experiment is something that should not be limited to the taking of medications. It is really a concept that may be expanded to apply to the whole gamut of interactions between patient and provider. Basically, what every clinician and every patient wants is to find the best solution for the patient’s problems and to establish a cooperative relationship so that the patient will carry out the plan successfully. Although this may seem like a simple objective, it is deceptively complicated.

As patient and provider come together, they bring different knowledge, skills, resources, anxieties, and expectations to the relationship. It is not like a chemical reaction, with a predictable product as a result of their interactions. Each patient is so different that each time therapy is prescribed, it is essentially a therapeutic experiment with that unique patient. It is important to share this attitude of engaging in a therapeutic experiment with the patient at the outset of working together so that the patient understands the variability of outcomes for each trial.

Patients must understand that many factors lead to the success of a therapeutic regimen. For example, two patients with the same problem both may take the same medication but may have entirely different outcomes. Thus, a continuing relationship with the health care provider is essential in making adjustments to discover the proper therapy for the individual patient.

Pressure was exerted on the faculty of a graduate nursing program by a psychologist who thought that all psychologists should gain prescriptive authority. He suggested that all the faculty had to do was to develop some videotapes for psychologists to view that would teach them how to prescribe medications. “It is as simple as following a recipe,” he maintained. Because he had never written a prescription, clearly, he underestimated both the knowledge base and the interpersonal skills required in the process of working with patients through the prescribing process.

Establishing Therapeutic Relationships in Treatment

The therapeutic experiment is implemented through the relationship established between the health care provider and the patient. This relationship will be therapeutic if it allows the goals of treatment to be met. Therefore, the major task of patient and provider is to establish a long-term relationship so that treatment, including the use of medications, will be implemented appropriately and effectively. It involves a stepwise process—identify a problem, assess it adequately, identify various potential solutions, examine the variables needed to judge the risk-benefit ratio of the solutions, choose the most appropriate solution, and, finally, identify the effects (both beneficial and adverse) that may result from implementation of the chosen solution (see Chapter 11 on making clinical decisions).Several factors are essential to establishing this therapeutic relationship. These include time, attitude, information, communication, and positive feedback.

Time

Establishing a relationship, particularly with those patients who seek primary care, requires an investment of time. This is especially so with elderly patients. Time is an especially scarce resource in today’s managed care environment. Actually, time is a wise investment in cost-effective treatment that is required early in the relationship to assess the patient’s status accurately through history taking and listening. Time invested by one consistent provider is required. Continuity of care is essential for collecting additional information and making modifications as the patient exhibits response to the initial therapy. Offices with policies that make it easy for patients and providers to have brief follow-up conversations by telephone, whenever either of them requires it, also help to make relationships more satisfying and successful.

Attitude

How the clinician uses time with the patient and what the clinician says to the patient reflect a basic attitude. This attitude is expressed in the answer to the question “Who owns the problem?” If the answer is that the patient owns the problem, then care is delivered with the attitude that the health care provider is there to assist the patient in getting or staying well. If the attitude is that the patient has a problem for the provider to solve, then the provider owns the problem and often hastens to solve it. This is an essential concept for clinicians to sort out in their minds because it fundamentally affects how the therapeutic relationship is established and defines the rules for continuing the relationship.

Information

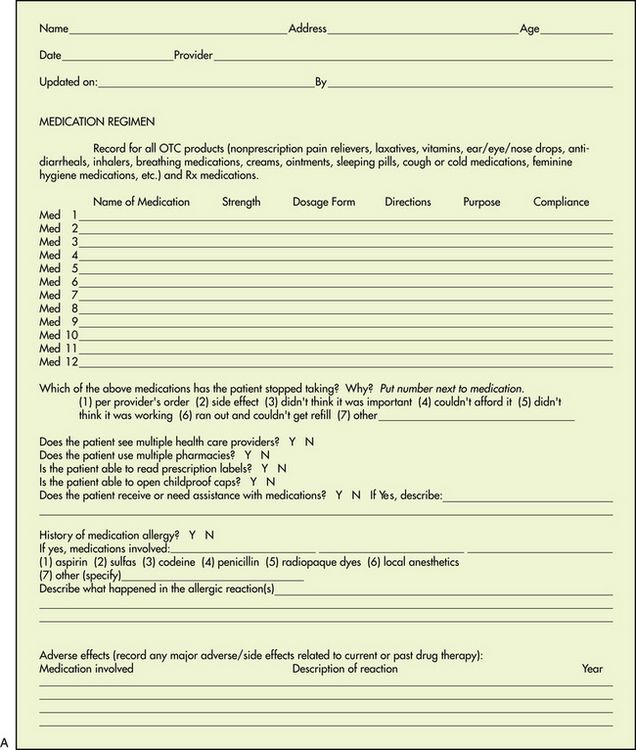

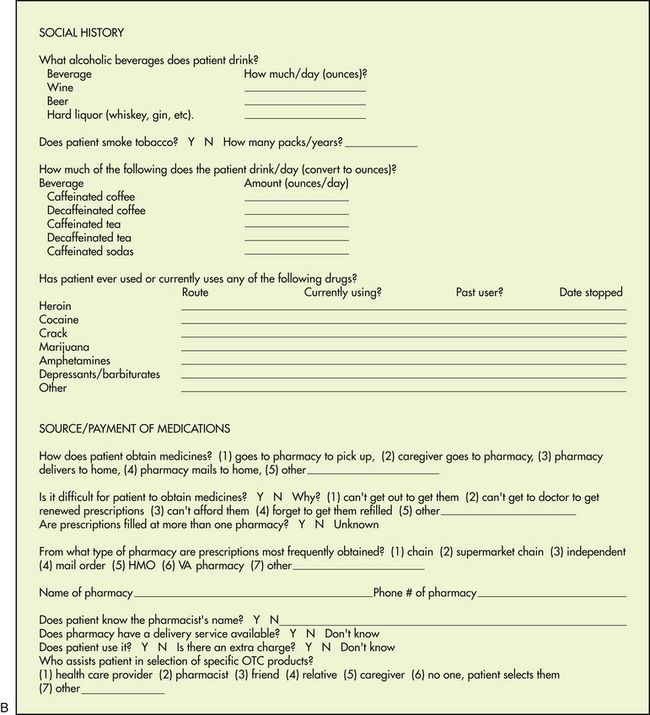

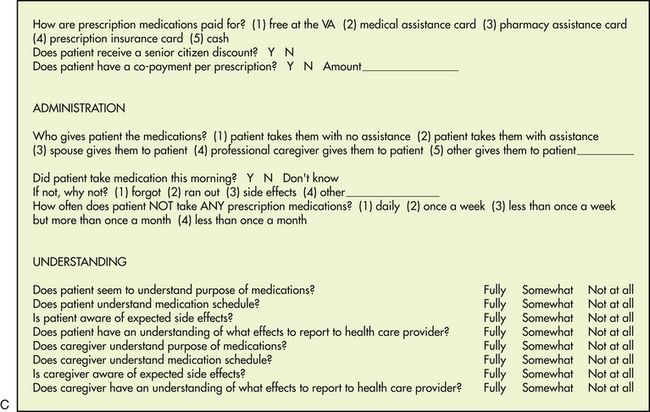

Expert diagnosticians have maintained that the most important part of information gathering is the history. Many formats have been established for collecting needed information about a patient. The open-ended questions of medical and nursing school are almost always abbreviated or reduced to checklists and forms by the experienced clinician in day-to-day clinical practice. It is important to obtain a comprehensive database for patients for whom pharmacologic therapy is anticipated, especially with regard to medications. This type of information often is best obtained by having patients fill out preprinted forms regarding their medication experience. Although it would be ideal to have this information before the first visit with the health care provider, the reality is that a comprehensive history may take several visits to acquire, with the health care provider collecting a little more information with each visit. Using a history-taking form about medications, such as that illustrated in Figure 9-1, helps to standardize the information collected and allows it to be expanded during several succeeding sessions. The information collected should not only be comprehensive but customized to the patient population (e.g., inner city, migrant, elderly) and to the specific problem under evaluation (e.g., cardiovascular, diabetes). If patient medications are to be adequately managed, an updated medication list should be part of every chart (Rooney, 2003) and should be updated routinely with every visit.

While some health care providers may not consider it, there is a growing trend among patients to want more access to their medical records. Researchers recently found that 22% of patients want to see and share their medical records, including provider notes, with family members and other medical providers. So health care providers need to clearly think about what they are preserving in the health records and how it reflects on their communication, attitudes, and provision of basic information (Walker et al, 2011).

Communication

A 2011 survey published in the British medical journal BMJ Quality & Safety showed that 89% of clinicians believed it was important to ask patients about their expectations of care, but only about 16% of them reported that they did so. Clearly, if clinicians do not ask their patients about their expectations, it is going to be difficult to meet them. In this study, nurses were more likely to discuss expectations with patients than physicians were (Rozenblum et al, 2011).

But just like patients, clinicians must ask themselves what is reasonable to expect from the patients with whom they work. Many patients will have relatively good health, knowledge about the things they should do to stay or get well, and resources to buy insurance, medications, or medical devices. Other patients have limitations that place in perspective what the clinician can do to help them. Environment, genetics, nutrition, and stress all play larger roles in a patient getting well than medicines and surgery.

A 2011 report calculated the relative risks of mortality for different social factors such as extent of education, poverty, employment status, health insurance status, job stress, presence of social support, racism or discrimination, housing conditions, and early childhood stressors. Prevalence estimates for each social factor were calculated using U.S. Census Bureau data. According to the report, “About 245,000 deaths in the United States in 2000 were attributable to low levels of education, 176,000 to racial segregation, 162,000 to low social support, 133,000 to individual-level poverty, 119,000 to income inequality, and 39,000 to area-level poverty. Altogether, 4.5% of deaths were found to be attributable to poverty, and risks associated with both low education and poverty were higher for individuals age 25-64 than for those 65 or older who qualified for Social Security and Medicare.” The report claimed that the number of deaths calculated as attributable to low education was comparable to the number caused by heart attack, the leading cause of U.S. deaths in 2000. The study concluded that the estimated number of deaths in the United States that were attributable to social factors is comparable to the number attributed to pathophysiologic and behavioral causes. These figures are compelling arguments for a broader public health conceptualization of the causes of mortality and a more expansive approach that considers how social factors should be addressed to improve the health of populations (Galea et al, 2011).

It may be that better use of electronic health records will help to address some of the factors that create health disparities. Being able to customize medical data collection to highlight unique problems of minority or poor individuals, electronically send prescriptions to a pharmacy, prevent drug–drug interactions, report adverse drug events, and remind patients to return for care may all be helpful to clinicians and patients.

Effective two-way communication between patient and health care provider requires a consistent commitment to respect the other’s role in the relationship. It involves more listening than speaking, but a true exchange of information and ideas is essential.

During the course of therapy, the patient’s expectations as expressed to the health care provider must be fulfilled. Transference, or the subconscious redirection to one person of feelings and attitudes toward others (e.g., parents, authority figures), may further influence the patient’s relationship with the health care provider in a positive or negative manner, depending on the patient’s previous experiences. All of these factors play a part in establishing honesty and trust in the patient–provider relationship.

Other strategies that have been identified as helpful in establishing a relationship with the patient include the health care provider’s friendliness; a positive, confident approach; a thoughtful response to patient complaints; encouraging patient questions; a supportive, nonjudgmental method of eliciting and responding to patient admissions of noncompliance; and encouraging patients to become actively involved in their own care. Techniques that encourage active patient participation as opposed to provider-dominated decisions, negotiating rather than dictating a treatment plan, and identifying and resolving barriers to compliance are also helpful. Finally, attempting to find congruence between patient and provider in their understanding of a problem and its management and efforts to motivate the patient and increase patient satisfaction are also helpful (Frishman, 2007; Goeman & Douglass, 2007; Swanson, 2003; Wilson et al, 2007).

Some of the specifics of what is communicated to the patient must focus on the therapeutic goals of treatment. When medications are involved, the nature of the experiment with that particular medication and that particular patient should be explored. Clear expectations must be communicated about mutual decision making, taking medications as ordered, returning for monitoring of effectiveness of the intervention, and the need to adjust dosages or medications over time.

Health care providers must refine listening and questioning skills. They must focus first on the patient, then on the environment, and then on themselves. Specifically, the tasks are to learn to judge the patient’s verbal or nonverbal cues to see whether the patient is ready to receive information. Providers should first attend to the physical environment of the discussion (privacy, freedom from distractions). And, finally, they must pay attention to their own mannerisms, tone of voice, and language. They should use active listening with feedback to ensure that the information sent is the same as the information received.

In the classic article by Chessare (1998) on teaching clinical decision making to physicians, the author maintains that after presenting information, the health care provider needs to elicit the patient’s preferences for health and other outcomes. For example, it is not enough to give a family the probability that a child will be left with significant morbidity after a potentially life-sustaining procedure. It is also necessary to have the parents consider what the morbidity may mean to them and their child. This discussion should include information on the child’s somatic and psychologic well-being in the context of family life and the financial repercussions for the family of specific clinical decisions (Chessare, 1998). A prudent course must be charted between creating uncontrolled and unfounded anxieties on the one hand and generating a false sense of equally groundless security and reassurance on the other.

To lead discussions of this type, health care providers need to understand how framing the problem for a decision maker can affect the decision. Health care providers must know some techniques for helping the patient or family deal with probabilities when making a particularly difficult decision. The provider should elicit preferences from patients and parents regarding the outcomes of medical treatment.

Health care providers also have a societal duty to consider the consequences of the decisions both they and the patients make for the greater good of the community. For example, the parents’ decision not to provide immunization for their child because of concerns about adverse reactions places others in the community at risk. When a higher-cost strategy gives no added benefit to the patient, then it is appropriate for the health care provider to use a lower-cost choice. When higher-cost strategies of potential benefit are available, the health care provider must be able to frame decisions for families such that they understand the expected added benefit (Chessare, 1998; Kraetschmer et al, 2006). For example, the family of a patient with tuberculosis might be convinced that it is in the interest of public safety for a judge to put the patient in jail until a supervised course of medication therapy can be concluded rather than allow the patient to remain noncompliant with drug therapy in the community. It is essential for providers to help the patient recognize that other factors, in addition to his own preferences, must be considered in the decision of whether to take medication for a particular problem.

Implicit in the communication process is the guarantee that once data about a problem have been presented clearly to a family, health care providers will do their utmost to provide the best therapy. It is part of the provider’s role to avoid strategies that provide no benefit to the patient. Practicing evidence-based medicine leads to cost-effective care because data are sought to validate strategies that lead to the best outcomes.

Providers also do not have the right to withhold effective therapies chosen by the family simply because they are more costly than others. Because managed care is about providing health care within budget constraints, the pressure to contain costs by limiting care is significant in most plans. This is especially true regarding drug therapy. This pressure is strongest in for-profit plans, where breaking even is not enough. It is now also seen with Medicaid patients, for whom drug choices may be severely limited by formularies for less costly, and sometimes less effective, medications. Ethically, providers must refrain from withholding strategies that are marginally superior to others simply because they are too expensive. This is sometimes difficult given the restrictions of some payment plans, but in some situations, to do otherwise is a violation of the patient–provider relationship (Kraetschmer et al, 2006).

If policies of a managed care organization or other organization would preclude the prescription of recommended therapy, the provider must continue to act as the family’s agent and help them obtain the desired care. When the provider cannot support the desires of the patient, he has a duty to make this clear to the patient. If the patient continues to see his desire as appropriate, the provider must assist him in finding another provider (Chessare, 1998; Kraetschmer et al, 2006).

Not only does communication have to be examined from a philosophical or procedural point of view, but specific information must be discussed in the patient encounter. The construction of a diagnostic plan is based on critical decision making. The problem itself must be clearly defined by some clinically measurable, verifiable means—for example, a lump in the breast can be defined as a malignant lesion only after pathologic examination. Only known information can be used to define a problem; no assumptions can be accepted in the problem definition.

The provider’s assessment of the patient’s history and physical and laboratory information will answer the questions “What etiology?” “Why now?” and “How severe?” This step allows for further refinement of the problem and speculation as to the probable causes and potential risk to the patient based on information gathered in the database. “What etiology?” suggests potential treatments of a correctable cause. “Why now?” is particularly important in acute exacerbations of chronic disease or detection of immune deficiencies, for it leads to an approach that treats the acute problem and prevents further difficulty. “How severe?” leads to decisions on the rapidity and perhaps the nature of treatment (see Chapter 11 on making clinical decisions).

Next, the therapeutic objective must be clearly defined and stated before treatment is begun. The goal or objective should be (1) realistically attainable with available therapeutic agents, (2) clearly related to the problem as defined and assessed, and (3) measurable.

Finally, the indices of therapeutic effect are determined. These measures of the therapeutic objective should be discriminating, identified, and relevant to the therapeutic objective. Identification of discriminating therapeutic indices allows the practitioner to recognize when the therapeutic objective has been achieved. It is the identification of those subjective and objective parameters that the practitioner will monitor to determine the degree of therapeutic achievement. These are often suggested from well-established clinical guidelines.

If the patient agrees to drug therapy, the provider must offer specific explanations about what medication the patient is to take and why (see Chapter 11 on making clinical decisions). The selected modality should be as specific for the problem and the therapeutic objective as possible. Evidence-based medicine will provide direction about what has proved effective. In the absence of definitive recommendations, agents or modalities will be selected on the basis of cost, efficacy, lowest toxicity, and other patient and drug variables.

Both patient- and agent-related variables must be considered in the final selection and administration of an agent. Agent-related variables are defined as those properties of any agent that are characteristic of that agent and that affect its use in a given situation. Examples of this would be chemical properties, formulation, absorption, metabolism and excretion, toxicity, half-life, and bioavailability (see Chapter 3 on pharmacokinetics).

Patient-related variables are defined as those preexisting conditions that in some way alter the expected effects of an agent on the patient—that is, renal function or dysfunction, liver function or dysfunction, age, weight, individual response, concomitant disease, the disease or problem itself, compliance or noncompliance, or allergy. Patient-related variables also may include absolute or relative contraindications for use of an agent in a given patient. An example would be the use of sympathomimetic amines in a hypertensive patient.

Detailed instructions must be given to the patient, preferably in writing, about how to take medication (see Chapter 11 on tips in writing prescriptions and Chapter 10 on design and implementation of patient education). One cannot rationally administer an agent without first understanding variables that affect its administration. Patients should understand what they might expect, both positively and negatively, when taking this medication.

And, finally, patients should understand their responsibility to report back to the provider about how the “experiment” is progressing. Direct observation of the chosen indices of effect and toxicity is the final and most important step in the implementation of the therapeutic experiment in the actual situation. This step involves eliciting subjective and objective data as a follow-up to administration of the agent. Obviously, there is no point in establishing a therapeutic objective unless providers will be able to know when the objective has been achieved or when a toxic index is being approached.

From the first discussions of therapy, patients must understand the providers’ expectations about having them return for laboratory tests and clinic appointments. Again, whether the report is on what patients have done to handle their problems or whether they report back on the success of the provider’s plan depends on the attitude that has been established about who owns the problem.

One example of a realistic expectation might be that the patient will bring all medications (e.g., current and recently discontinued, prescription and OTC, internal and topical, liquid and solid) with him in a bag for follow-up visits. Reviewing the medications together, validating that the medications were taken as ordered, and noting the number of pills that are left are all important ways in which the provider can assess whether the patient has been compliant.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree