Type

Macroscopic description

I

Esophageal atresia; no tracheoesophageal fistula (8%)

II

Esophageal atresia with upper-pouch fistula (upper pouch connected to the trachea; 1%)

III

Esophageal atresia with lower-pouch fistula (lower pouch connect to the trachea or main-stem bronchus; 86%)

IV

Esophageal atresia with upper- and lower-pouch fistula (1%)

V

Tracheoesophageal fistula; no atresia (4%)

♦

Newborns present in the first few days of life with regurgitation, choking, aspiration, and cyanosis

♦

Complete atresia is rare (1:30,000 live births), but atresia associated with tracheoesophageal fistula is more common (1:3000–4000 live births). Atresia is usually associated with other abnormalities, including cardiac, genitourinary, and skeletal

Achalasia

Clinical

♦

Achalasia is an esophageal motility disorder secondary to failure of relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter. Although usually idiopathic, achalasia may be secondary to Chagas disease, sarcoidosis, intrathoracic malignancies, or numerous inflammatory conditions. Adults typically are affected, but achalasia does occur occasionally in children. There is an increased risk of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), if untreated

♦

Classically, barium studies show a distal “beak-like” deformity and proximal dilatation. End-stage achalasia is often characterized by a sigmoid appearance to the esophagus, usually requiring esophagectomy

Macroscopic

♦

The esophagus shows proximal dilatation with distal fibrosis, stenosis, and ulceration. Mucosa may have a cerebriform appearance from marked squamous hyperplasia

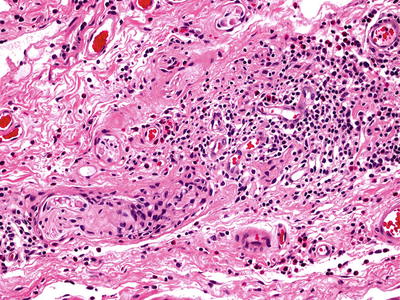

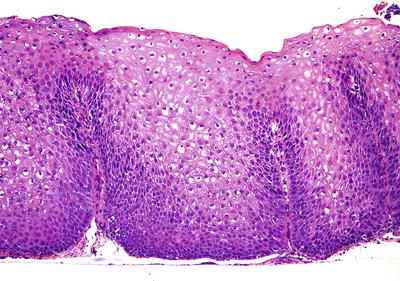

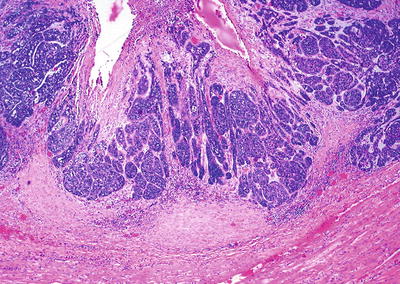

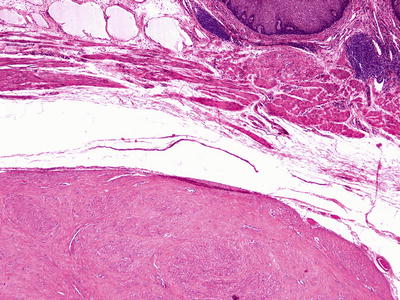

Microscopic (Fig. 41.1)

♦

The histologic hallmark is the loss of myenteric ganglion cells with a myenteric lymphocytic infiltrate. Secondary changes include hypertrophy of all muscle layers, squamous hyperplasia, and fibrosis in end-stage disease

Fig. 41.1.

Achalasia.

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Scleroderma (systemic sclerosis) is an important diagnostic consideration. The hallmark of esophageal scleroderma is fibrosis of the inner circular layer of the muscularis propria. The wall can be paper thin rather than hypertrophied as in achalasia

Glycogenic Acanthosis

Clinical

♦

Glycogenic acanthosis is very common and is found in 15–30% of individuals, usually in the distal esophagus. Patients are typically asymptomatic, but the endoscopic differential includes candidiasis and ulcer exudate

♦

It is occasionally associated with the PTEN hamartoma syndrome (10q23.3 mutations), including Cowden syndrome (facial trichilemmoma, acral keratosis, gastrointestinal (GI) hamartomatous polyposis)

Macroscopic

♦

The gross appearance typically consists of uniform, round to oval, white, longitudinally oriented plaques. The plaques may be single or multiple and are usually small (<3 mm)

Microscopic

♦

The squamous mucosa is hyperplastic with glycogenization of the superficial cells but may be indistinguishable from normal

Cysts

Clinical

♦

See Table 41.2

Table 41.2.

Types of Cysts

Type | Microscopic description |

|---|---|

Bronchogenic | Ciliated columnar (respiratory epithelial lining; wall with smooth muscle, mucous glands, cartilage) |

Esophageal | Stratified squamous lining; wall with muscularis mucosae, submucosal glands |

Duplication | Squamous, gastric (fundic), ciliated columnar or small intestinal epithelial wall with muscularis mucosae, submucosa, and muscularis propria |

Pseudodiverticula | Squamous metaplasia of esophageal glands and ducts |

♦

The majority of cysts are asymptomatic, but patients (both children and adults) may present with dysphagia and cough

Macroscopic

♦

Generally, the esophagus is dilated

Diverticula

♦

See Table 41.3

Table 41.3.

Types of Diverticula

Type | Location | Etiology |

|---|---|---|

Zenker | Upper third | Weakness in the muscle wall |

Traction | Lower third | Caused by attachment of inflamed lymph nodes |

Epiphrenic | Immediately superior to the diaphragm | Unknown |

Heterotopic Gastric Mucosa (Inlet Patch)

Clinical

♦

One to ten percent of patients undergoing upper endoscopy have an inlet patch, usually in the cervical esophagus

♦

Endoscopically, inlet patches are identified as an island of columnar mucosa surrounded by squamous mucosa

♦

These are congenital anomalies, not true metaplasias; therefore, there is no increased risk of malignancy, although case reports of adenocarcinoma arising within an inlet patch do exist

Macroscopic

♦

Inlet patches appear as an orange-reddish patch with sharply demarcated borders

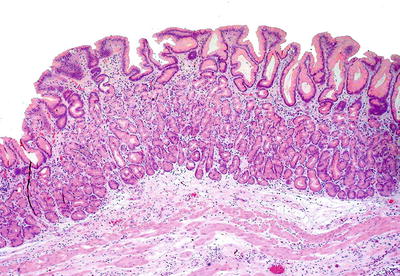

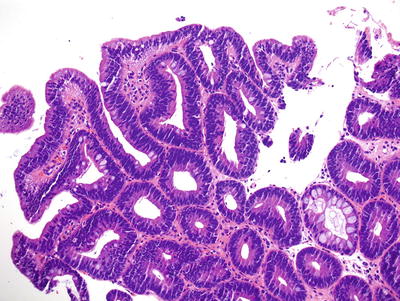

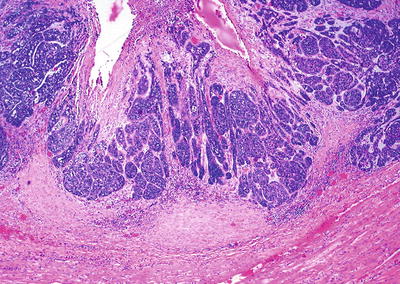

Microscopic (Fig. 41.2)

♦

Gastric-type mucosa with fundic glands or foveolar-type epithelium is the typical histologic finding, but goblet cells may be present. These patients probably do not require Barrett-type surveillance; however, some do advocate endoscopic surveillance of inlet patches with intestinal metaplasia

Fig. 41.2.

Inlet patch.

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Adenocarcinoma:

Inlet patches lack an infiltrative pattern or cytologically malignant glands

♦

Barrett esophagus:

This is caused by gastroesophageal reflux; thus, the metaplasia begins at the gastroesophageal junction and extends proximally. Unlike Barrett, inlet patches generally are not considered to be preneoplastic, and only rare cases of cancer arising in inlet patches have been reported

Esophagitis

Caustic (Corrosive)

Clinical

♦

Common agents include alkali (drain openers) and acids (cleaners, battery fluids). Children typically present as an accidental ingestion while adults more often an intended suicide attempt

♦

Signs and symptoms vary but include nausea, vomiting, dysphagia, refusal to drink, abdominal pain, increased salivation, and oropharyngeal burns

♦

Upper endoscopy is the most reliable method to document the extent of injury to the esophagus and stomach and thus predicts prognosis. Injury occurs most commonly at sites of esophageal narrowing (aortic arch). Endoscopy may not be necessary if the patient is asymptomatic without swallowing difficulties

♦

Radiography may show mediastinitis, pneumonitis, pleural effusion, or perforation. Stricture formation is the most common chronic complication, usually when a circumferential burn occurred

Macroscopic

♦

Depending on the severity of exposure and underlying agent, the endoscopic appearance varies from erythema and ulceration to extensive tissue necrosis and even perforation

Microscopic

♦

Biopsies are rarely taken in the acute phase, but these may show mucosal congestion, ulceration, or necrosis. Biopsies are more frequently taken to assess the chronic complications that may develop such as fibrosis and strictures

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Infectious esophagitis

Fungal organisms may be identifiable (e.g., Candida), and special stains such as Gomori methenamine silver (GMS) may be helpful. Characteristic viral cytopathic effect (e.g., herpes simplex virus [HSV], cytomegalovirus [CMV]) may be seen

Pill Induced

Clinical

♦

This form of esophagitis is due to prolonged contact of medication with esophageal mucosa and is often associated with drinking inadequate fluid or lying down after ingesting medications

♦

Multiple different medications have been implicated, including doxycycline, ferrous sulfate, NSAIDs, alendronate, chemotherapeutic drugs, and many others

Macroscopic

♦

Pill esophagitis tends to occur in the mid-esophagus (narrowed by aortic arch) and is marked by erythema and/or ulceration surrounded by normal mucosa

Microscopic

♦

Active inflammation with eosinophilic infiltration and occasional ulceration is typical; these features may be indistinguishable from reflux esophagitis or eosinophilic esophagitis

♦

Rarely, polarizable or iron-stainable material is found

Sloughing Esophagitis (Esophagitis Dissecans Superficialis)

Clinical

♦

This often unrecognized condition most commonly involves elderly patients who present with severe pain. Often, they have multiple comorbidities and are taking multiple medications

Macroscopic

♦

The sloughed epithelium can often be grossly identified as a detached layer of thin, whitish degenerating mucosa with a “tissue paper”-like appearance

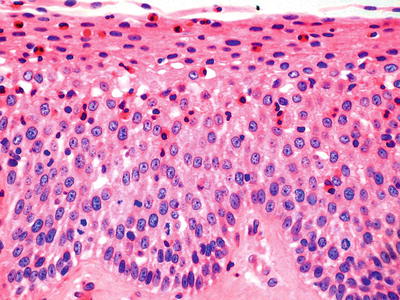

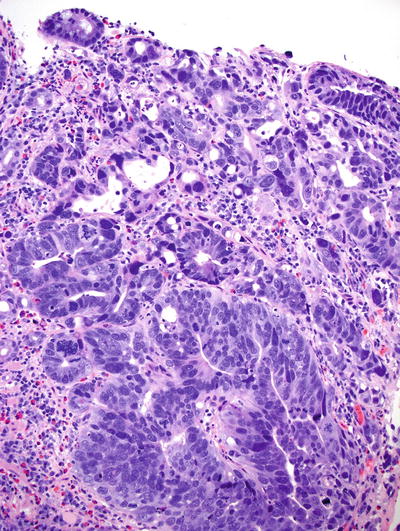

Microscopic (Fig. 41.3)

♦

A split mucosa with bulla formation is seen in which the superficial, detached portion may appear necrotic, inflamed, or normal. There may be orthohyperkeratosis or parakeratosis, and bacterial colonies may be present. An eosinophilic band may be seen where the separation has occurred

Fig. 41.3.

Sloughing esophagitis .

Radiation

Clinical

♦

The esophagus is the second most tolerant GI organ to radiation (rectum is first), but radiation esophagitis may still develop as a consequence of radiotherapy directed at pulmonary, mediastinal, or esophageal neoplasms

♦

Patients may complain of dysphagia, odynophagia, or retrosternal burning with acute injury. Acute toxicity only rarely causes bleeding or perforation. Dysphagia is the most common chronic complaint, usually because of stricture. Fistula formation may also occur as a chronic complication

Macroscopic

♦

Endoscopic features include erythema, ulceration, necrosis, and telangiectasia

Microscopic

♦

Endoscopic biopsies usually only show nonspecific active esophagitis with ulcer and granulation tissue

♦

More characteristic changes of radiation-induced injury include bizarre epithelial and stromal cells with low N/C ratio and “smudgy” chromatin, vascular sclerosis, hyalinized collagen, and submucosal fibrosis

Eosinophilic

Clinical

♦

Eosinophilic esophagitis is a clinicopathologic entity that requires exclusion of pathologic gastroesophageal reflux via refractoriness to standard antireflux medical therapy or normal pH on manometry

♦

Children are affected more commonly than adults and males more than females. Patients may present with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD)-like symptoms of heartburn and regurgitation. Other symptoms include dysphagia, food impaction, and abdominal pain. Children may present with failure to thrive, food refusal, and feeding intolerance

Macroscopic

♦

Although not pathognomonic, the following endoscopic appearances have been associated with eosinophilic esophagitis: linear furrowing, vertical lines along the esophageal mucosa, white exudates, white specks, nodules, granularity, transient or fixed circular rings, linear shearing/crepe paper mucosa, and strictures. Endoscopic-pathologic correlation is critical to the diagnosis

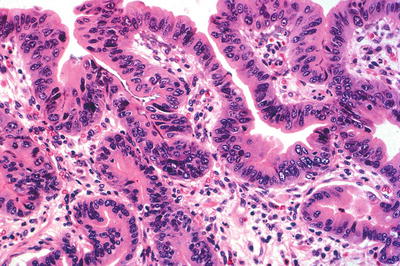

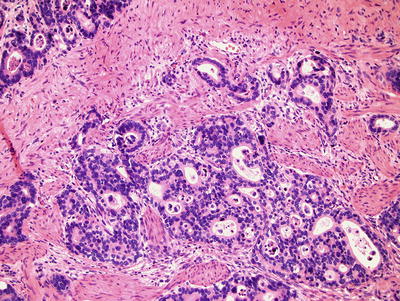

♦

Histologically, there is a marked intraepithelial eosinophilic infiltrate with at least one HPF demonstrating ≥15 intraepithelial eosinophils. Superficial eosinophil layering and eosinophilic microabscesses (tight clusters of >4 eosinophils) are also helpful clues to the diagnosis

♦

Less specific changes include basal cell hyperplasia, elongated papillae, lamina propria fibrosis, and other accompanying intraepithelial inflammatory cells

♦

Histopathologic changes seen in idiopathic eosinophilic esophagitis are not specific, and increased esophageal eosinophils may also be found in eosinophilic gastroenteritis, GERD, allergy, parasite infection, drug hypersensitivity, pill-induced esophagitis, or connective tissue disease. Biopsy of mid/proximal esophagus is recommended and may be helpful in excluding GERD

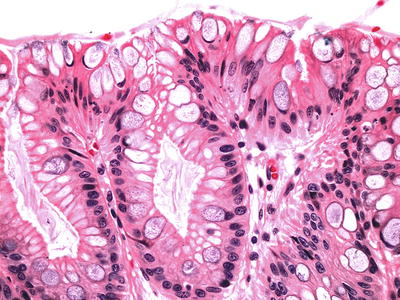

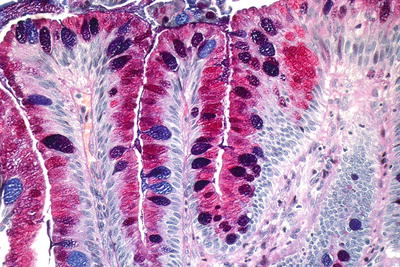

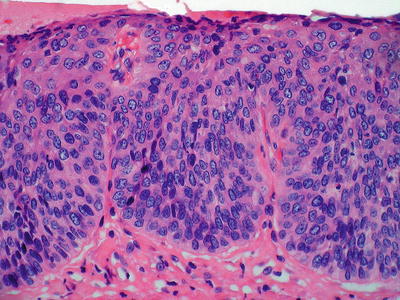

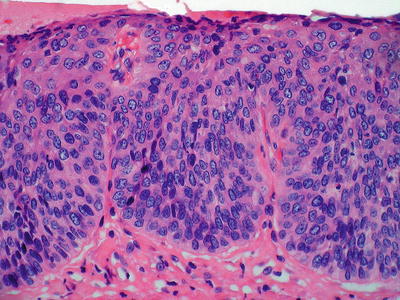

Fig. 41.4.

Eosinophilic esophagitis.

Fig. 41.5.

Eosinophilic esophagitis .

Lymphocytic

Clinical

♦

Lymphocytic esophagitis is a pattern of injury in which our understanding is evolving, and some pathologists prefer to use a more descriptive term such as “increased intraepithelial lymphocytes.” It is thought to be associated with a variety of conditions including gastroesophageal reflux disease, celiac disease, atopy, or contact injury. Additionally, a subset of patients (particularly children) with this pattern of injury are thought to have esophageal involvement by Crohn’s disease

Macroscopic

♦

Findings most often are those of endoscopically unremarkable esophageal mucosa or features compatible with gastroesophageal reflux disease

Microscopic

♦

Most commonly, intraepithelial infiltrates of CD3-positive lymphocytes are seen in a predominantly peripapillary or parabasal location. There is often associated spongiosis, and occasional intraepithelial granulocytes may accompany the lymphocytic infiltrate

Infectious

Candida Species

Clinical

♦

Symptoms in most patients are from C. albicans, even when C. glabrata or C. tropicalis is coisolates. However, highly immunosuppressed patients may suffer from non-C. albicans disease. Affected patients often have some predisposing risk factor, such as extremes of ages, diabetes mellitus, transplantation, leukemia, lymphoma, AIDS, head and neck radiation, broad-spectrum antibiotics, or corticosteroids. Some patients have no apparent risk factors

♦

The hallmark symptom is odynophagia, often localized retrosternally, and most cases are accurately diagnosed with endoscopic brushing and biopsy. Complications are rare but include deep invasion, systemic dissemination, strictures, and intramural pseudodiverticulosis

Macroscopic

♦

The classic endoscopic appearance consists of multiple yellow–white discrete or confluent plaques with erythematous, edematous, and friable mucosa of the mid- or distal esophagus. Many patients also show oral thrush

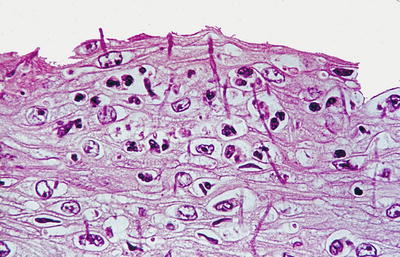

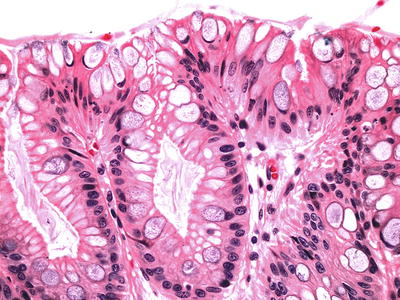

Microscopic (Fig. 41.6)

♦

Given the ubiquity of Candida, invasion into tissue or fibrinopurulent exudate by budding yeasts and pseudohyphae must be identified. True hyphae also may be seen. PAS and GMS can confirm the diagnosis. Bacterial colonization of ulcers is a frequent associated finding

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Hyalohyphomycoses:

♦

These fungi are characterized by true septate hyphae with acute angle branching and may be confused with Candida. Important hyaline septate molds include Aspergillus spp., Fusarium spp., and Pseudallescheria boydii, and these organisms may be refractory to Candida therapy. The specific organism must be identified by a validated method (e.g., culture, PCR, etc.), because histology is not a reliable means of differentiation

Herpes Simplex Virus

Clinical

♦

The esophagus is the organ most commonly involved by HSV in immunodeficient patients, such as those affected by malignancy, radiotherapy, or immunosuppressive therapy, but healthy adults and children can be affected. All affected adults show serologic evidence of a previous infection

♦

Symptoms include odynophagia, nausea, vomiting, hematemesis, and fever, which are frequently preceded by 3–7 days of upper respiratory infection. HSV is transmitted through direct contact, and shedding of viable virus is seen in 2% of adults

♦

The diagnosis is based on identifying HSV by histology, cytology, and culture. Culture may only represent colonization, so histologic correlation is important

Macroscopic

♦

The mucosa shows sharply demarcated vesicles that evolve into shallow ulcerations. Severe cases demonstrate extensive mucosal denudation

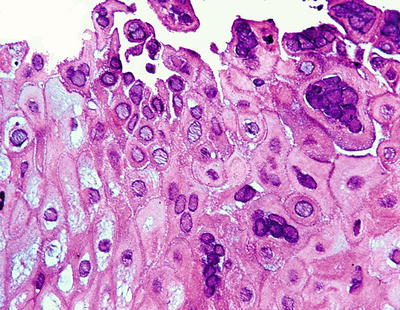

Microscopic (Fig. 41.7)

♦

Nonspecific ulceration with a neutrophil-rich inflammatory ulcer in an at-risk patient is the first clue and warrants close examination for diagnostic HSV changes

♦

HSV cytopathic effect is best identified within the squamous cells at the edge of the ulcer; therefore, sampling is always an issue

♦

The classic changes include “ground glass” nuclei and Cowdry type A (dense eosinophilic) nuclear inclusions along with the “3 Ms”—nuclear molding, chromatin margination, and multinucleation. HSV immunostain is available for confirmation or if diagnostic cytopathic changes are not seen

Cytomegalovirus

Clinical

♦

Infection with CMV is most frequently seen in posttransplant (60–70%) and AIDS patients and is rare among immunocompetent patients

♦

Patients may be asymptomatic or experience a mild mononucleosis-like syndrome. Other possible symptoms include odynophagia, nausea, vomiting, GI bleeding, and fever

♦

Similar to HSV, diagnosis is based on histology, cytology, and culture. Culture may only represent colonization, hence histologic correlation is important

Macroscopic

♦

The endoscopic appearance is similar to HSV, usually characterized by discrete erosions or ulcers

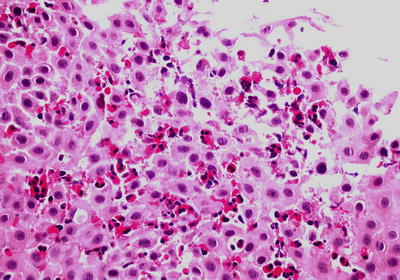

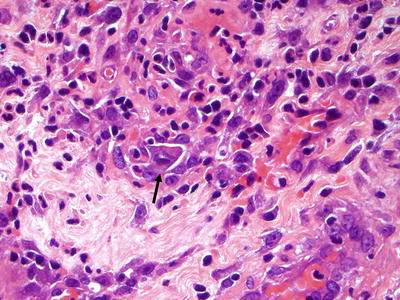

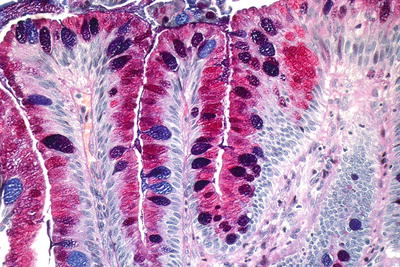

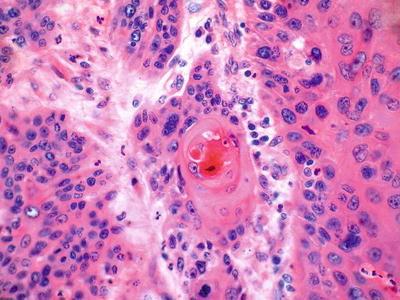

Microscopic (Fig. 41.8)

♦

In contrast to HSV-targeting squamous cells, CMV cytopathic effect is best identified in the ulcer bed mesenchymal cells. CMV infection causes conspicuous intranuclear inclusions (“owl eye”) surrounded by a halo as well as intracytoplasmic granular inclusions. Treated or early infections may not be as characteristic, and immunostaining can prove invaluable

Fig. 41.6.

Candida esophagitis.

Fig. 41.7.

Herpes esophagitis.

Fig. 41.8.

Cytomegalovirus inclusion.

Dermatologic Disease

Pemphigus Vulgaris

Clinical

♦

Occurs in predominantly middle-aged to elderly patients. This is the most common of the autoimmune blistering diseases (see Chapter 19) to involve the esophagus, and the majority of afflicted patients do show esophageal involvement

Macroscopic

♦

Flaccid bullae of various sizes

Microscopic

♦

Intraepithelial blisters show extensive acantholysis, and basal cells remain attached to the basement membrane (“tombstone layer”). A superficial mixed inflammatory infiltrate, including eosinophils, may be present

Lichen Planus

Clinical

♦

An autoimmune inflammatory disease that often involves extensor surfaces of the skin and is associated with occasional oral mucosal as well as esophageal involvement

Macroscopic

♦

Areas of mucosal hyperemia, mucosal plaques, or mucosal sloughing may be seen in the upper or mid-esophagus

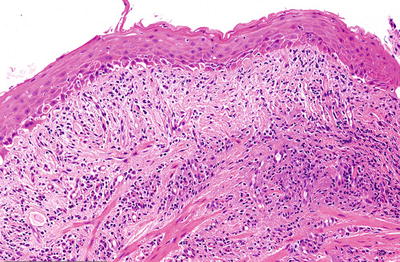

Microscopic (Fig. 41.9)

♦

A subepidermal lichenoid inflammatory infiltrate is seen with occasional dyskeratotic keratinocytes

Fig. 41.9.

Lichen planus.

Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease

Clinical

♦

GERD is the most frequent cause of esophagitis, affecting 20–40% of the population. Patients present with regurgitation, heartburn, pain, and dysphagia. The pathogenesis is poorly understood, since some degree of reflux is a normal physiologic process. Actual disease probably results from an imbalance between reflux and acid resistance of the esophageal epithelium

♦

GERD is associated with hiatal hernia, acid hypersecretion (e.g., Zollinger-Ellison syndrome [ZES]), nasogastric intubation, pregnancy, diabetes, and scleroderma

Macroscopic

♦

Changes predominantly affect the distal esophagus, consisting of hyperemia, erosion/ulceration, and strictures. Up to 50% of patients show either no or only minimal abnormalities

Microscopic (Fig. 41.10)

♦

No single specific diagnostic criterion exists, and the features may be similar to those seen in pill-induced, corrosive, radiation, and eosinophilic esophagitis and even physiologic reflux. Therefore, clinical correlation is imperative

♦

Epithelial hyperplasia, evidenced by basal cell proliferation >15% of the total epithelial thickness and lengthened lamina propria papillae >67% of the epithelial thickness is helpful but requires well-oriented sections. Dilatation and congestion of capillaries in the superficial lamina propria papillae are a soft sign

♦

Intraepithelial eosinophils may be particularly useful in mal-oriented biopsies; greater than six eosinophils per biopsy have been cited as a minimum cutoff in adults

♦

Increased intraepithelial lymphocytes (>10hpf) are often seen; neutrophils indicate more severe epithelial injury with erosion, ulceration, and granulation tissue representing the most severe GERD manifestation. Atypical, “bizarre” mesenchymal cells and multinucleated cells may be present in the granulation tissue

Fig. 41.10.

Gastroesophageal reflux changes .

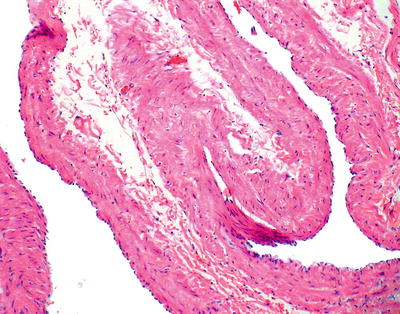

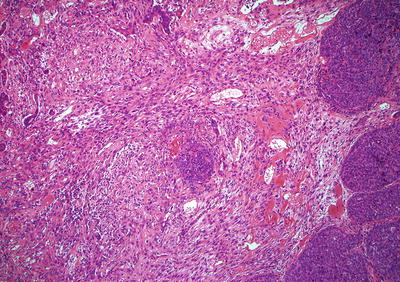

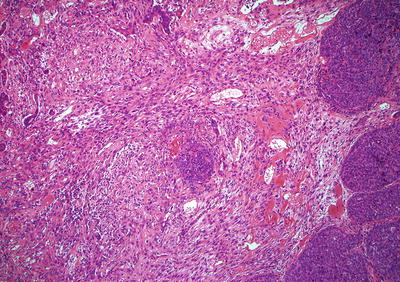

Varices (Fig. 41.11)

Fig. 41.11.

Varices.

Clinical

♦

Varices occur when portal vein pressures exceed 12 mmHg

♦

Etiology: see Table 41.4

Table 41.4.

Etiology of Varices

Cirrhotic | Noncirrhotic |

|---|---|

Hepatitis | AV fistula |

Splenomegaly | |

Fatty liver disease | Splenic/portal vein thrombosis |

Chronic biliary disease | Idiopathic portal hypertension |

Toxins | |

Schistosomiasis | |

Malignancy | |

Sarcoidosis | |

Nodular regenerative hyperplasia | |

Focal nodular hyperplasia | |

Hepatic vein thrombosis | |

Veno-occlusive disease | |

Right-sided heart disease |

Macroscopic

♦

The endoscopic appearance is characterized by prominently congested blood vessels in the mucosa with short, bright red, curved streaks on the surface of the varices

Sebaceous Gland Metaplasia

Clinical

♦

Sebaceous gland metaplasia is very rarely detected at upper endoscopy as small yellow papules. It is, however, found microscopically in 2% of autopsy series. Sebaceous glands have been found at all levels of the esophagus, usually with multifocal involvement

♦

These lesions have not been described in children, indicating that they are likely a metaplastic phenomenon

Microscopic

♦

One sees sebaceous glands in the lamina propria or epithelium, often with an accompanying lymphocytic infiltrate or associated reflux-type changes, if located in the distal esophagus

Barrett Esophagus

Clinical

♦

Chronic reflux is the only established predisposing factor for Barrett esophagus (BE), causing reepithelialization of the squamous-lined esophagus by a more acid-resistant columnar mucosa. In general, BE is considered irreversible

♦

About 3–12% of patients with symptomatic GERD harbor BE. The incidence increases with age, and older Caucasian adult males are the most commonly affected group

♦

The diagnosis requires both endoscopic and histopathologic confirmation. BE is considered a preneoplastic lesion and is the only known risk factor for glandular dysplasia and adenocarcinoma. The risk of adenocarcinoma in BE patients is about 0.25% per year

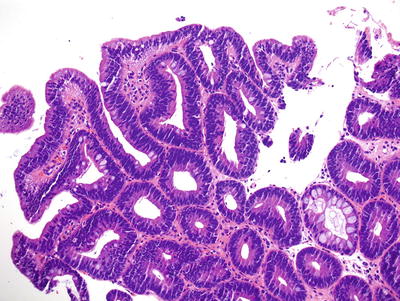

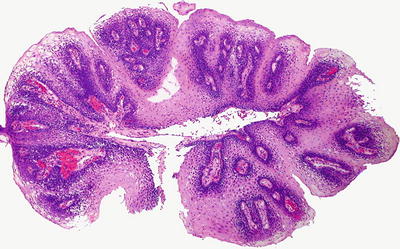

Macroscopic (Fig. 41.12)

♦

Columnar-type epithelium of any length must be identified in the distal tubular esophagus. Flat, salmon-pink mucosa involving a portion of the lower tubular esophagus is the typical gross appearance

Fig. 41.12.

Barrett esophagus.

♦

Intestinal metaplasia (IM) of the tubular esophagus characterized by columnar epithelium with goblet cells is required for the diagnosis. Goblet cells can be confirmed by their characteristic blue staining on Alcian Blue at pH 2.5

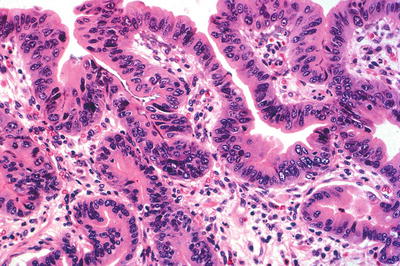

Fig. 41.13.

Barrett esophagus, negative for dysplasia.

Fig. 41.14.

Barrett esophagus, Alcian Blue/PAS.

♦

A newly developed muscularis mucosae is often located directly underneath the metaplastic glands. It is especially important to be aware of this “double muscularis mucosae” in patients who develop intramucosal adenocarcinoma, so as to avoid overcalling submucosal invasion

♦

Grading of dysplasia suffers from interobserver variability, and “expert” confirmation is recommended (Table 41.5; Figs. 41.15 and 41.16). A diagnosis of high-grade dysplasia (HGD) often leads to therapeutic intervention, including various ablation therapies or endoscopic mucosal resection

Table 41.5.

Dysplasia in Barrett Esophagus

Negative | Indefinite for dysplasia | Low grade dysplasia | High-grade dysplasia |

|---|---|---|---|

–Regular glands –Mild nuclear crowding and hyperchromasia restricted to the basal portion –Maturation onto the surface | –Mild cytoarchitectural changes with surface involvement; falls short of low-grade dysplasia –Marked changes, but evaluation of surface involvement is not possible –Obscuring inflammation present | –Mild architectural distortion with discrete glands –Nuclear enlargement, crowding, and hyperchromasia extending to surface epithelium –Preservation of nuclear polarity (long nuclear axis perpendicular to the basement membrane) | –Distortion of crypt architecture (marked crowding, villiform, cribriform, or back-to-back glandular patterns) –Marked nuclear enlargement, crowding, hyperchromasia, and pleomorphism –Loss of nuclear polarity –Dilated glands containing necrotic debris |

Fig. 41.15.

Barrett esophagus with low-grade dysplasia.

Fig. 41.16.

Barrett esophagus with high-grade dysplasia.

♦

Less commonly, Barrett dysplasia is characterized by a “gastric type” or “foveolar type” of dysplasia. These cases should remain associated with intestinal metaplasia. This type of dysplasia is more difficult to recognize and grade since the characteristic nuclear stratification, elongation, and polarity alterations are typically absent. Criteria for dysplasia grading in gastric-type dysplasia are evolving but remain rooted in epithelial architecture and cytology (nuclear size and nucleoli)

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Intestinal metaplasia of the cardia:

The esophagogastric junction (EGJ) is most reliably identified by the most proximal extent of the gastric folds; however, this may also be challenging endoscopically. EGJ IM in patients without apparent BE is relatively common and therefore almost certainly does not have the same neoplastic risk as BE

Morphologic features of BE rather than cardiac intestinal metaplasia include crypt disarray, incomplete and diffuse intestinal metaplasia, multilayered epithelium, squamous epithelium overlying intestinal metaplasia, hybrid glands, and IM in the vicinity of esophageal glands/ducts

A number of immunohistochemical markers have been evaluated, including CK7/CK20, hep par-1, CDX-2, and CD10, but none have been found to be particularly clinically useful

♦

Pancreatic acinar metaplasia:

This is composed of benign pancreatic acinar cells without goblet cells and is of little diagnostic significance

♦

Inlet patch:

Inlet patches are composed of gastric-type mucosa that may harbor goblet cells but is surrounded by squamous mucosa and is not in continuity with the GEJ

Neoplastic: Epithelial

Squamous Papilloma

Clinical

♦

Squamous papillomas are the most common benign epithelial neoplasm but are actually quite rare (0.01–0.04%) and are typically incidentally found. Generally, these are not considered to be premalignant

♦

Human papilloma virus (HPV) has been implicated in the pathogenesis, but evidence of HPV DNA in these lesions is conflicting in the literature

Macroscopic

♦

Most papillomas are small (<5 mm) and arise in the distal esophagus. Endoscopically, they may appear cauliflower-like and polypoid, sessile (verrucoid), or as smooth nodules (endophytic)

Microscopic (Fig. 41.17)

♦

Squamous papillomas demonstrate exophytic growth with fibrovascular cores. Orderly maturation is preserved, and cytologic atypia is lacking. HPV changes, including koilocytosis, binucleation, hypergranulosis, and enlarged nuclei, are inconsistently present

Fig. 41.17.

Squamous papilloma.

Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Clinical

♦

SCC is the most common neoplasm of the esophagus worldwide, but the incidence differs significantly in different countries. North America and Western Europe are considered “low risk,” with African-Americans and men over 50 years disproportionately affected in these regions. In the USA, the incidence roughly equals that of the esophageal adenocarcinoma

♦

Risk factors include smoking, alcohol, consumption of food rich in nitrates and nitrosamines, hot beverages, achalasia, chronic stricture, tylosis, and Plummer-Vinson syndrome. HPV as an etiologic agent is controversial

♦

SCC often presents at a late stage with patients complaining of dysphagia and weight loss . In about 60%, there are lymph node metastases at diagnosis. The overall prognosis is poor with an overall 5-year survival rate of 10%, although this rate is slightly higher (30–40%) for those patients treated with esophagectomy. The prognosis is most closely linked to tumor stage and lymph node metastases

Macroscopic

♦

The most common sites are the middle and lower thirds of the esophagus. Esophageal squamous carcinomas may be multifocal in up to 20% of patients. The masses are gray-white and circumferential with sharply demarcated margins and fungating, ulcerative, or infiltrative configuration. “Superficial” carcinomas are limited to the mucosa and submucosa

Microscopic (Fig. 41.18)

♦

The histology is similar to SCC of other sites with enlarged, often vesicular nuclei, densely eosinophilic cytoplasm, and intercellular bridges. Desmoplasia, mitotic rate, pleomorphism, and degree of keratinization vary from case to case, and gland formation is not uncommon. Invasion is expansile or infiltrative, but submucosal spread can occur up to 5 cm beyond grossly visible margins. Vascular invasion occurs in up to 75% of cases

Fig. 41.18.

Invasive squamous cell carcinoma.

Immunohistochemistry

♦

p63 (nuclear) and cytokeratin 5/6 are sensitive and specific markers of squamous differentiation

Precursor/Related Lesions

♦

Squamous dysplasia (Fig. 41.19):

Fig. 41.19.

High-grade squamous dysplasia.

Squamous dysplasia is found at the periphery of 60–90% of invasive cancers

Similar to glandular esophageal neoplasia, squamous dysplasia may be graded as low grade or high grade. Dysplastic features include nuclear overlapping, pleomorphism, increased N/C ratios, architectural disarray, and lack of maturation

In general, if the dysplastic epithelia are confined to basal half of the epithelium, then the lesion is considered low grade; if the dysplasia occupies more than one-half of the epithelium with more severe cytologic alterations, then the dysplasia is of high grade. Carcinoma in situ corresponds to full-thickness dysplasia and may be considered as the end of the spectrum of HGD

Variants

♦

Spindle cell carcinoma (Fig. 41.20):

Fig. 41.20.

Spindle cell carcinoma.

These are also known as carcinosarcoma, polypoid carcinoma, or sarcomatoid carcinoma and often exhibit intraluminal, exophytic growth with a short, thick stalk and a smooth or knobby surface. Because of the growth pattern, mural invasion is often limited, portending a better prognosis for these lesions

Histologically, the tumors are often biphasic with both squamous carcinoma and sarcoma-like spindle cell elements. About 10% will show malignant stromal differentiation toward bone, cartilage, or skeletal muscle. These tumors are pankeratin positive (often only focal)

♦

Basaloid squamous carcinoma (Fig. 41.21):

Fig. 41.21.

Basaloid squamous carcinoma.

The clinical features and prognosis are similar to those of typical SCC. The tumor cells grow in solid nests and are large with hyperchromatic, pleomorphic nuclei, and scant cytoplasm. Occasional gland-like spaces are seen. Palisading at the periphery of the nests with central necrosis is characteristic. The mitotic rate is high

♦

Verrucous carcinoma:

The tumor resembles its counterparts at other sites, characterized by a large, exophytic papillary mass. Histologically, the tumor is composed of spires of well-differentiated squamous epithelium with minimal cytologic atypia. Keratohyalin granules are characteristically inconspicuous. The invasive border is blunt and pushing, and there is typically a striking chronic inflammatory reaction

The natural history is not well defined, but esophageal verrucous carcinomas tend to grow slowly with very low metastatic potential

Adenocarcinoma

Clinical

♦

The incidence of esophageal adenocarcinoma is dramatically increasing, disproportionately affecting Caucasian males in their sixth to seventh decades. Adenocarcinoma represents approximately half of all esophageal carcinomas in the USA and is the second most common esophageal malignancy worldwide

♦

Ninety-five percent arise in Barrett metaplasia, which engenders a 30- to 125-fold risk of adenocarcinoma. However, most patients with Barrett will not develop adenocarcinoma. Case reports exist of adenocarcinoma developing in non-Barrett mucosa such as esophageal glands and heterotopic gastric mucosa

♦

The prognosis is poor (~20% 5-year survival) because most patients present at an advanced stage

Macroscopic

♦

Most adenocarcinomas are situated in the lower third of the esophagus. The gross appearance is variable and ranges from small, slight mucosal irregularities or plaques to large masses. The tumors are typically flat and ulcerated (70%) but may be polypoid and fungating (30%). Neoadjuvant therapy may eliminate all visible tumors

♦

Accompanying adjacent Barrett metaplasia can usually be identified. Most are well- to moderately differentiated intestinal-type adenocarcinomas, but mucinous, papillary, signet ring, or squamous differentiation can occur

♦

Typical malignant features of nuclear hyperchromasia, cellular pleomorphism, and increased mitotic rate are usually present. The glands are often abortive and have a jagged, infiltrative growth pattern. Occasionally, tumors are so well differentiated that submucosal invasion, rather than the aforementioned cytoarchitectural features, is required to establish the diagnosis. Submucosal infiltration is often characterized by a desmoplastic stromal response

Fig. 41.22.

Intramucosal adenocarcinoma arising in Barrett esophagus.

Fig. 41.23.

Invasive esophageal adenocarcinoma .

Differential Diagnosis

♦

High-grade dysplasia:

The distinction of HGD from intramucosal adenocarcinoma (IMC) is often difficult, particularly on biopsy. By definition, HGD is an intraepithelial neoplastic process, without disruption of the basement membrane. While HGD may be characterized by highly crowded glands, the finding of a never-ending glandular pattern, sheets of malignant cells, markedly angulated/distorted glands, or individual cells infiltrating the lamina propria is more characteristic of intramucosal adenocarcinoma. Additionally, the findings of cribriform glands or dilated glands with intraluminal necrotic debris should prompt consideration of a possible adenocarcinoma as opposed to only HGD

Adenosquamous Carcinoma

Clinical

♦

This is a rare aggressive malignancy with a prognosis comparable to squamous carcinoma. Squamous differentiation in adenocarcinoma or glandular differentiation in squamous carcinoma may be seen, but these are usually minor components. When malignant glandular and squamous components coexist in relatively equal proportions, the neoplasm can be considered an adenosquamous carcinoma

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Mucoepidermoid carcinoma:

One must recognize the classic triphasic differentiation , characterized by an intimate admixture of islands of squamous elements, intermediate cells, and mucus-secreting cells rather than distinct malignant squamous and glandular elements

Small Cell Carcinoma

Clinical

♦

The esophagus serves as the most common extrapulmonary site for small-cell carcinoma and it is seen most commonly in men aged 50–60 years. Risk factors include smoking and achalasia. Patients typically present at an advanced stage, and the prognosis is very poor with an average survival of <6 months

Macroscopic

♦

Tumors may be polypoid, fungating masses, or stenotic lesions with ulceration. These malignancies most commonly arise in the distal half of the esophagus

Microscopic

♦

Similar to pulmonary small-cell carcinoma, small-cell carcinoma of the esophagus is composed of solid sheets , nests, or ribbons of small blue cells with diffuse infiltration and nuclear molding. Cells are round oval with scant cytoplasm and hyperchromatic nuclei with speckled chromatin and frequent mitotic figures. Nucleoli are indistinct

Immunohistochemistry

♦

Keratin AE1/AE3, CAM 5.2, synaptophysin, and chromogranin are positive in most cases, but these may be weak and patchy

Neoplastic: Mesenchymal

Leiomyoma

Clinical

♦

More common in males (M:F=2:1) with average age at diagnosis of 45–50 years. Patients may complain of chest pain or dysphagia if the tumor is large

♦

Leiomyomas are the most common mesenchymal tumor in the esophagus, usually arising from the inner circular layer of the muscularis propria. Leiomyomas are often difficult to see endoscopically, but radiography reveals a well-defined intramural mass

Macroscopic

♦

Ninety percent occur in the lower and middle thirds of the esophagus, and most are only a few millimeters in size. They are usually sessile, single, well-circumscribed nodules but may be polypoid or multiple. Leiomyomas are firm, rubbery masses with a pale pink-white, lobulated, and whorled cut surface

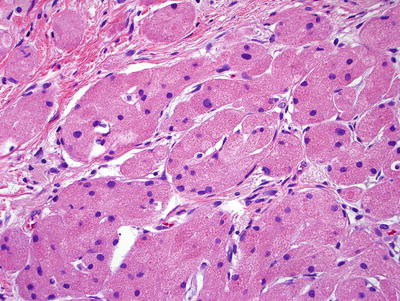

Microscopic (Fig. 41.24)

♦

Leiomyomas are composed of fascicles of mature, hypertrophic smooth muscle cells. The nuclei are bland and monomorphic, and mitotic figures are absent to rare. So-called symplastic leiomyomas with striking nuclear atypia have been described; mitotic activity should be very low without tumor necrosis. Hyalinization is common in esophageal leiomyomas

Fig. 41.24.

Leiomyoma.

Immunohistochemistry

♦

Smooth muscle actin and desmin are usually diffusely and strongly positive. In general, CD117, DOG1, and CD34 are negative excluding GIST; however, especially in deep leiomyomas, a nonneoplastic yet hyperplastic proliferation of interstitial cells of Cajal (ICC) may occur within the leiomyoma, mimicking a GIST

Granular Cell Tumor

Clinical

♦

Granular cell tumor is the second most common stromal tumor in the esophagus and usually is found in patients in their fifth to sixth decade of life as an incidental finding. Males are affected more commonly than females and African-Americans more so than Caucasians

♦

Characteristic endoscopic features of a sessile, yellow–white, firm lesion with intact epithelium can be strongly suggestive of granular cell tumor. The prognosis is generally excellent

Macroscopic

♦

These are small tumors, usually located in the distal esophagus and may be multiple in a minority of patients

Microscopic (Fig. 41.25)

♦

The tumor is superficial and composed of plump epithelioid cells with small nuclei and abundant eosinophilic granular cytoplasm. The cells are arranged in nests or clusters and are separated by collagenous septa

♦

Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia of the overlying epithelium is common, and misdiagnosis of SCC is a potential pitfall

Fig. 41.25.

Granular cell tumor.

Immunohistochemistry

♦

Granular cell tumors are typically diffusely S-100 protein and CD68 immunoreactive. The tumor is thought to be derived from peripheral nerves, and the CD68 immunoreactivity results from the abundant cytoplasmic lysosomes, which also impart the cytoplasmic granularity

Fibrovascular Polyp

Clinical

♦

Although fibrovascular polyps are rare, they are the most common benign intraluminal neoplasm in the esophagus, affecting males three times more frequently than females. Patients are usually in their sixth to seventh decade and asymptomatic; however, patients may also complain of dysphagia or respiratory symptoms, including acute respiratory distress

♦

Radiographic findings include a long, smooth, mobile, intraluminal mass with a spectrum of appearances depending on the predominant underlying histologic component. Local excision is curative and justified to relieve symptoms and prevent the risk of regurgitation with subsequent asphyxiation

Macroscopic

♦

More than 80% are located in the upper third of the esophagus with a mean length of 15 cm. They have a characteristic long, slender shape and pedunculated configuration. Rarely, the tip of the polyp may ulcerate and serve as a source of upper gastrointestinal bleeding

Microscopic

♦

Histology is variable, consisting of a mixture of collagenous to myxoid stroma, numerous dilated blood vessels, fat, and a chronic inflammatory infiltrate with overlying normal to hyperplastic squamous mucosa

Neoplastic: Miscellaneous Tumors

Lymphoma

Clinical

♦

The esophagus is the least common primary site of lymphoma in the GI tract; usually, the esophagus is involved secondarily. Symptoms mimic those seen in carcinoma

Macroscopic

♦

Esophageal lymphoma may present as a polypoid mass or thickened folds with proximal esophageal dilatation

Microscopic

♦

Almost all esophageal lymphoma have a B-cell phenotype , either large B cell or MALT type, but rare case reports of Hodgkin lymphoma and T-cell lymphoma exist

Melanoma

Clinical

♦

This is an extremely rare (<0.5% of all primary esophageal tumors) esophageal malignancy, usually arising in men over 50 years. Prognosis is extremely poor with average 5-year survival of 2%

Macroscopic

♦

These are usually found in the lower esophagus as a pigmented, polypoid mass

Microscopic

♦

Histologically, these share similar features with cutaneous melanoma, being characterized by nests of large, atypical melanocytes with hyperchromatic and bizarre nuclei and prominent eosinophilic nucleoli. The growth pattern varies from epithelioid to spindled

♦

Although cytoplasmic melanin granules are usually found, amelanotic variants do occur; immunohistochemical confirmation can be quite helpful. An adjacent junctional melanocytic component can help to substantiate the esophagus as the primary site of origin

Immunohistochemistry

♦

Almost all melanomas are at least focally S-100 protein+. Melan A, HMB 45, tyrosinase, MITF, and SOX-10 are important melanocyte markers to help confirm the diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Melanoma may have a variety of histologic appearances, making the list of possible differential diagnoses broad. Immunohistochemistry is often necessary in narrowing this differential diagnosis

♦

Carcinomas often have an epithelioid appearance and possibly signet ring cells; they are pankeratin+, while S-100 protein–, LCA–, Melan A–, and HMB 45–. Lymphoma demonstrates discohesive cells with scant cytoplasm; they are LCA+ and usually CD20+, but pankeratin–, S-100 protein–, Melan A–, and HMB 45–. Sarcomas are usually spindled and pankeratin–, LCA–, and HMB 45–

Metastatic

Clinical

♦

The most common primary sites of metastases to the esophagus are the lung, breast, and skin (melanoma); clinical information is crucial to rule out a primary lesion. Metastases most commonly involve the submucosa of the middle third of the esophagus without mucosal involvement

Staging Esophageal Malignancies

♦

See Table 41.6

Table 41.6.

Anatomic Stage/Prognostic Groups—Esophageal and Esophagogastric Junction Carcinoma

Squamous cell carcinoma | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Grade | Location | ||||

Stage 0 | Tis | N0 | M0 | 1 | Any |

Stage IA | T1 | N0 | M0 | 1 | Any |

Stage IB | T1 | N0 | M0 | 2 or 3 | Any |

T2 or T3 | N0 | M0 | 1 | Lower | |

Stage IIA | T2 or T3 | N0 | M0 | 1 | Upper, middle |

T2 or T3 | N0 | M0 | 2 or 3 | Lower | |

Stage IIB | T2 or T3 | N0 | M0 | 2 or 3 | Upper, middle |

T1 or T2 | N1 | M0 | Any | Any | |

Stage IIIA | T1 or T2 | N2 | M0 | Any | Any |

T3 | N1 | M0 | Any | Any | |

T4a | N0 | M0 | Any | Any | |

Stage IIIB | T3 | N2 | M0 | Any | Any |

Stage IIIC | T4a | N1 or N2 | M0 | Any | Any |

T4b | Any | M0 | Any | Any | |

Any T | N3 | M0 | Any | Any | |

Stage IV | Any T | Any N | M1 | Any | Any |

Adenocarcinoma | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Grade | |||||

Stage 0 | Tis | N0 | M0 | 1 | |

Stage IA | T1 | N0 | M0 | 1 or 2 | |

Stage IB | T1 | N0 | M0 | 3 | |

T2 | N0 | M0 | 1 to 2 | ||

Stage IIA | T2 | N0 | M0 | 3 | |

Stage IIB | T3 | N0 | M0 | Any | |

T1 or T2 | N1 | M0 | Any | ||

Stage IIIA | T1 or T2 | N2

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

| |||