Overview

Humans are diverse—one size does not fit all

Ergonomics and human factors aim to design both work and the workplace to fit the user

Taking an ergonomic approach involves understanding the user from the commissioning of a work system through design, building and testing

Work elements that affect humans such as posture or mental workload can be modified by job design

Human performance including safe behaviour is influenced by time pressure, experience and fatigue

Basic Concepts

The terms human factors and ergonomics are synonymous, ergonomics being used in the United Kingdom and human factors in the United States. According to the International Ergonomics Association, Ergonomics (or human factors) is the scientific discipline concerned with the understanding of interactions among humans and other elements of a system, and the profession that applies theory, principles, data and methods to design in order to optimize human well-being and overall system performance.

Ergonomists seek to understand the work system, the human-system interactions both physical and psychological and develop work systems or solutions with allied professions such as engineering, psychology and occupational medicine.

Within ergonomics there are three broad areas of specialism: physical ergonomics (anatomy, anthropometry, workplace design and layout, manual handling, upper limb disorders and environmental ergonomics); cognitive ergonomics (mental workload, decision making, human computer interaction, human reliability, human error and stress); and organizational ergonomics (sociotechnical systems, safety culture, job design and cooperative work). Ergonomists often work across domains or in specific areas, such as patient safety, where a multifaceted approach is required.

Epidemiology

Internationally, the majority of self-reported sickness absence is due to backache and muscular pain. This is closely followed by issues of fatigue and stress. The role of the ergonomist in analysing issues within the workplace is in examining the work system; identifying potential hazards (which can be physical and/or psychological); and developing risk reduction measures either through workplace redesign, job redesign or organizational change. This often involves working in conjunction with other professionals in occupational health, psychology or engineering.

Many sources of problems can be removed from a work system through effective design of the physical environment, particularly the workplace size and layout and consideration of the end user and their role in the system. Unfortunately, ergonomic considerations at the outset are often omitted, leaving problems to be addressed either by changing the workplace dimensions or adding warnings to the system after commissioning. The physical environment also has an impact on the postures adopted when working so can have either a positive or negative effect.

Consideration of ergonomics is an important aspect of the design of workplaces and equipment used therein. Poorly designed equipment can directly influence the chance of human errors occurring. For example, the layout of controls and displays can influence safety if switches are placed so that they can inadvertently be knocked on or off, or if controls are poorly identified and can be selected by mistake, or when critical displays are not in the user’s normal field of view. The controls on different pieces of equipment may not be compatible; for example, a switch in the up position may be ‘on’ in one case but ‘off’ in another. An analysis of the Kegworth (UK) air crash in 1989, identified that the aircraft had undergone a change in design and the pilots were not aware of all the changes; thus they mistakenly switched off the right-hand engine when it was the left-hand engine that was on fire. The vibration indicators would have highlighted this but they were known to be unreliable in previous aircraft so were effectively ignored and their new design (small with a needle going around the outside) did not help comprehension.

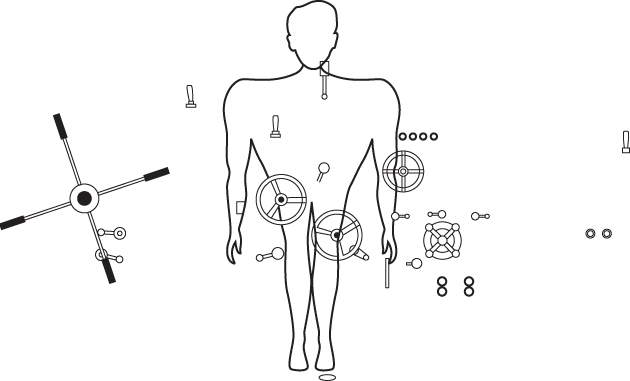

Alarm systems are sometimes designed so that high-priority alarms are not clearly differentiated and are thus easily missed. Figure 16.1 shows the dimensions an individual should possess in order to use the layout of controls presented.

Figure 16.1 Arrangement of the controls on a lathe and ‘ideal’ operator who should be 1.3 metres tall, 61 cm across the shoulders with a 2.4-metre arm span.

Many sources of human error can be removed through effective design of equipment and procedures. Such ‘error-tolerant’ designs consider the tasks that the equipment is intended for and the errors the user may make. For example, accidental administration of vincristine intrathecally rather than intravenously has been recognized as a major risk to patients. The appreciation of this risk resulted in changes to the process of prescribing and administering the drug, the labelling of the drug, the use of a minibag system and recommendations on equipment design. This redesign process examined the whole work system, the people involved and the processes and equipment they used.

Designing tasks, equipment and workplaces to suit the users can prevent or reduce human errors and thus accidents and ill health. A key message is that effective use of ergonomics will make work safer and more productive.

At-Risk Occupations

Ergonomic problems can exist in all workplaces but problems are more prevalent in certain industries. Musculoskeletal problems are more prevalent in construction and agriculture as are physical hazards such as exposure to extreme thermal environments—heat and cold, wind and humidity or lack of it. A high mental workload is characteristic of certain jobs such as air-traffic control, offshore working and other safety critical work and high emotional demand characteristics of healthcare, social work and teaching where the research base is now informing better practice.

Management in the Workplace

When managing ergonomic risks there are a number of approaches that can be taken depending on the risk factor and whether there is relevant legislation that has to be complied with. Box 16.1 lists some initial considerations to be made when procuring equipment for the workplace. For example, in preventing back injuries in the UK, there is a requirement to carry out a risk assessment for all work tasks where there is a risk of injury to the person carrying out the task (Manual Handling Operations Regulations 1992 as amended 2004). The risk assessment should also be followed up by risk reduction measures such as redesigning the workplace, the work organization and the task. Although training in lifting and handling is one risk reduction measure, this should be seen as a last resort in relation to manual handling tasks and not just because its effectiveness has been called into question—primary prevention is almost always more effective. Research on the prevention of work-related upper limb disorders has been published to identify the source of problems (not always ergonomic ones) and again risk reduction measures may be feasible. The relevant ergonomic input is to evaluate the workplace, the work organization and the tools in use. To reduce the risk of work-related upper limb disorders occurring, it is necessary to assess the postures adopted by the individual, the level of repetitiveness of the work tasks, the vibration from tools and the force requirements of the job. Risk reduction measures may include workplace redesign to ensure the workplace fits the user, the use of different tools to reduce postural strain and reorganization of the work to reduce the level of repetitiveness of the task. Some factors to consider when assessing workplaces are listed in Box 16.2. Notwithstanding this ergonomic approach to prevention as with heavy lifting tasks, training may have a place. A participatory approach to workplace changes and involving managers, supervisors and employees in change is key to the success of any risk reduction approaches.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree