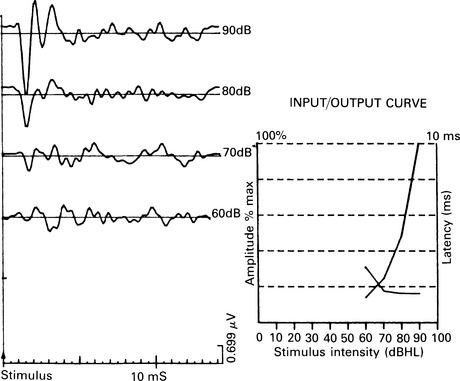

13 Until the infant is 4 months of age, the quality of the auditory responses is little dependent on mental development, and only later can auditory behaviour and developmental landmarks differentiate the normal child and the child whose functioning and behaviour are abnormal (Northern & Downs 1984). A battery of audiological tests is applied according to the auditory and mental development of the child. Some children’s behaviour and functioning is such that it is difficult to judge their auditory responses to conventional audiometric behavioural tests. Precise audiometric threshold estimation may be desirable in such a child, and objective hearing assessment, using ERA tests, may greatly contribute. Delaying the detection of hearing loss and therapy may deprive the child of critical time in learning auditory skills, and may further compromise the development of his speech and behaviour. Catlin (1978) reported that 50% of cases of childhood deafness occur within the first year of life, and most of these cases are congenital. Martin (1982) reported the prevalence of hearing loss of 50 dB or more, in all children aged 8 years in the European Economic Community (EEC), as ranging from 0.74–1.48 per 1000. A wide variety of clinical problems in children of various ages leads to referral for an objective test of hearing, in order to verify the degree of hearing loss and institute the best rehabilitation programme. It has been shown that the time interval between objective hearing estimation with ECochG or ABR and the first ‘reliable’ pure-tone audiogram may be several years, and that this was obtained at some stage in 31% of 841 tested children (Bellman et al 1984). Some important single features or combinations of salient features in children of various ages, exhibiting both normal intelligence and mental handicap, who may require objective hearing assessment, are listed below: Mental retardation with or without severe behavioural problems Cerebral palsy with gross motor involvement Speech and language delay or absence Family history of hearing loss Neither mental retardation, nor central auditory disorder, nor autism result, in themselves, in hearing loss, but when behavioural auditory responses suggest hearing loss, or pure-tone audiograms are not credible, these conditions have to be verified. However, it is possible for such children to have peripheral hearing loss. For example, in mental institutions, the prevalence of hearing loss and ear disease ranges from 10 to 45% or higher (Northern & Downs 1984). Brain-damaged, autistic, or hyperactive children who have difficulty in paying attention for any length of time may be difficult to test with conventional audiometric methods; they are prime candidates for ERA. Some children with neurological handicaps and visual disability have delay of language and of other developmental characteristics. They often fail behavioural audiometric tests and are classified as ‘the deaf-blind’ child; however, on testing them later, it may appear that some of them have normal hearing (Stein et al 1981). Various eye–ear syndromes, congenital neuromuscular disorders, and rubella can be associated with deafness. ECochG is a very useful procedure when applied in ‘difficult-to-test’ children (Fig. 13.1). Assessment of hearing at the level of the cochlea is obtained from the stimulated ear only, and there is no contribution from the better ear at high-intensity stimulation level when there is a sound crossover effect. Click-evoked ECochG is the most sensitive test, especially for moderately severe to severe hearing loss, and the correlation with the pure-tone audiogram at 1000, 2000, and 4000 Hz is very good. Correlation between the ECochG threshold and the behavioural threshold in free field in difficult-to-test children was found to be good, although the differences between the two values increased with increase of hearing loss (Bergholtz et al 1977). ECochG is a comparatively quick test, and responses can be obtained in 128 to 256 samples. Its disadvantage is difficulty in assessing hearing at lower frequencies, and the responses correlate best with the hearing level for audiometric frequencies above 1000 Hz.

ERA in the ‘difficult-to-test child’

CLINICAL PROBLEM

Population

CHOICE OF ERA TESTS

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Basicmedical Key

Fastest Basicmedical Insight Engine