II. IDIOPATHIC FOCAL EPILEPSIES

Partial seizures may be a significant component of three important syndromes: benign childhood epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes, early-onset benign childhood occipital epilepsy, and late-onset occipital epilepsy.

A. Benign Childhood Epilepsy with Centrotemporal Spikes (BCECTS, Rolandic Epilepsy)

1. Definitions and Etiology

BCECTS is an important, distinct epileptic syndrome occurring in childhood that is characterized by nocturnal tonic-clonic seizures of probably focal onset and diurnal simple partial seizures arising from the lower rolandic area of the cortex. The EEG pattern is characteristic, consisting of midtemporal-central spikes. The clinician must be aware of this syndrome because evaluation and prognosis differ considerably from those of other focal seizure disorders.

BCECTS is limited to the pediatric age group. Seizures begin between the ages of 2 and 12 years, although more typically, the child is between 5 and 10 years of age. Seizures of BCECTS remit spontaneously and do not occur after 16 years of age. The developmental and neurologic examination is usually normal.

The disorder is usually familial. Fifty percent of close relatives (siblings, children, and parents of the probands) demonstrate the EEG abnormality between the ages of 5 and 15 years. Before 5 and after 15 years of age, penetrance is low, and few patients demonstrate the abnormality. Only 12% of patients who inherit

the EEG abnormality have clinical seizures. The EEG trait of midtemporal-central spikes has been linked to chromosome 15q14. However, the inheritance of the epilepsy appears to have a multifactorial inheritance.

2. Seizure Phenomena

The syndrome also is termed benign rolandic epilepsy because of its characteristic feature, partial seizures involving the region around the lower portion of the central gyrus of Rolando. Although a nocturnal tonic-clonic seizure is the most dramatic and common mode of initial presentation, diurnal simple partial seizures may also demand a neurologic evaluation.

The characteristic features of daytime seizures include (a) somatosensory stimulation of the oral-buccal cavity, (b) speech arrest, (c) preservation of consciousness, (d) excessive pooling of

saliva, and (e) tonic or tonic-clonic activity of the face. Less often, the somatosensory sensation spreads to the face or arm. On rare occasions, a typical jacksonian march of tonic or tonic-clonic activity occurs.

Although the somatosensory aura is quite common, this history is frequently not elicited, especially in young patients. Motor phenomena during the daytime attacks are usually restricted to one side of the body and include tonic, clonic, or tonic-clonic events. These attacks most frequently involve the face, although the arm and leg may be involved. Although seizures rarely generalize during wakefulness, the sensory or motor phenomena may change sides during the course of the attack. Arrest of speech may initiate the attack or occur during its course. Consciousness is rarely impaired during the daytime attacks. After the seizure, the child may feel numbness, pins and needles, or “electricity” in his or her tongue, gums, and cheek on one side. Postictal confusion and amnesia are unusual after seizures in BCECTS. In nocturnal seizures, the initial event is typically clonic movements of the mouth with salivation and gurgling sounds from the throat. Secondary generalization of the nocturnal seizure is common. The initial focal component of the seizure may be quite brief.

The seizures may occur both during the day and during the night, although in most children, seizures are most common during sleep. Daytime and nocturnal seizures are both brief. The frequency of seizures in BCECTS is typically low, and for status epilepticus to develop is unusual.

3. Electroencephalographic Phenomena

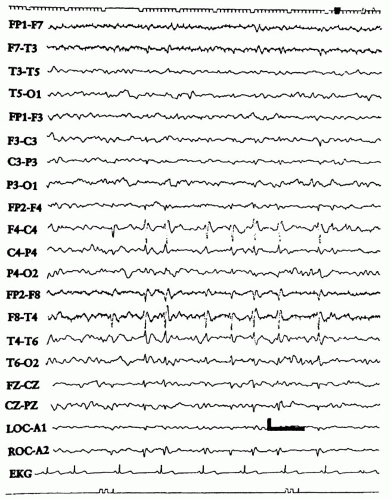

BCECTS is characterized by a distinctive EEG pattern. The characteristic interictal EEG abnormality is a high-amplitude, usually diphasic spike with a prominent, following slow wave. The spikes or sharp waves appear singly or in groups at the midtemporal (T3, T4) and central (rolandic) region (C3, C4) (

Fig. 6-1). The spikes may be confined to one hemisphere or occur bilaterally. Rolandic spikes usually occur on a normal background.

Occasional records show generalized spike-wave discharges, usually during sleep. Most children with BCECTS who have spike-wave discharges during sleep do not have typical absence seizures.

Sleep usually increases the number of spikes. Because approximately 30% of children with BCECTS have spikes only during sleep, an EEG should be obtained during sleep from children suspected to have the syndrome. Sleep states are usually normal in BCECTS.

4. Management

If the patient has a clinical history and the EEG characteristics of BCECTS and a normal neurologic examination, further workup is not necessary. If the neurologic examination is abnormal or the EEG demonstrates abnormalities other than the typical epileptiform discharge, further evaluation with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is recommended.

Because of the benign nature of BCECTS, many physicians may choose not to treat the first or second seizure. If treatment is initiated, the seizures are usually controlled with a single antiepileptic drug. Drugs used for partial seizures (e.g., phenobarbital, phenytoin, carbamazepine, oxcarbazepine, and valproic acid) are usually effective.

The EEG is not a good predictor of recurrence risk. Most patients can be tapered off medications after 1 to 2 years of seizure control, regardless of whether the EEG normalizes.

5. Prognosis

The prognosis of BCECTS is generally good, with the majority of children going into remission by the teenage years. However, in a small percentage of patients with BCECTS, deficits in verbal

memory or language skills develop. Children with BCECTS should be monitored closely for school performance.

B. Childhood Epilepsy with Occipital Paroxysms (CEOP)

1. Definition

Two distinct forms of CEOP are found. The early-onset type, or Panayiotopoulos syndrome, occurs in young children with a peak of onset at 5 years. The late-onset, or Gastaut, type has an age at onset of around 8 to 9 years. Both syndromes are associated with occipital spikes.

2. Seizure Phenomena

The early-onset type, or Panayiotopoulos syndrome, is characterized by ictal vomiting and deviation of the eyes, often with impairment of consciousness and progression to generalized tonic-clonic seizures. The seizures are infrequent and often solitary, but in around one third of the children, the episodes evolve into partial status epilepticus. Two thirds of the seizures occur during sleep. The late-onset, or Gastaut, type consists of brief seizures with mainly visual symptoms, such as elementary visual hallucinations, illusions, or amaurosis, followed by hemiclonic convulsions. Postictal migraine headaches occur in half of the patients.

3. Electroencephalographic Phenomena

The interictal EEG in both conditions is characterized by normal background activity and well-defined occipital discharges. The occipital spikes are typically high in voltage (200 to 300 mV) and diphasic, with a main negative peak followed by a relatively small positive peak and a negative slow wave. The discharges may be unilateral or bilateral and are increased during non-rapid eye movement sleep. An important feature in this syndrome is the prompt disappearance with eye opening and reappearance 1 to 20 seconds after eye closure.

4. Differential Diagnosis

Patients with CEOP should be differentiated from children with occipital spikes occurring during both eye opening and eye closure. These children are usually younger than 4 years of age. Only approximately half of the children in studies with occipital spikes have seizures. Unlike CEOP, these children typically do not have visual phenomena or postictal headaches.

Additional words of caution regarding occipital spikes are necessary. The syndrome of CEOP requires more than the EEG finding of occipital spikes for diagnosis. As is the case with centrotemporal spikes, a reactive occipital spikes pattern does not develop in all children with seizures. Occipital spikes are seen in other disorders. Children with myoclonic, absence, and photosensitive epilepsies may have similar EEG findings, but they are not classified as having benign occipital epilepsy (BOE). Occipital spikes also can be seen in young children with visual disorders, Sturge-Weber syndrome, epilepsy with bilateral occipital calcification, late infantile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis, and other occipital structural lesions.

5. Prognosis

The prognosis in the early-onset (Panayiotopoulos) type is excellent, and it typically resolves within several years of onset. The prognosis in the late-onset (Gastaut) form is variable. Although most patients have a benign course, seizure control may be difficult in some patients. Although seizures may continue into adulthood, many children outgrow their seizures.