KEY TERMS

Notifable disease/Reportable disease

Charles-Edward Amory Winslow, the great public health leader of the early 20th century, called epidemiology “the diagnostic discipline of public health.”1(p.vii) Epidemiologic methods are used to investigate causes of diseases, to identify trends in disease occurrence that may influence the need for medical and public health services, and to evaluate the effectiveness of medical and public health interventions. Epidemiology is used to perform public health’s assessment function called for in the Institute of Medicine’s The Future of Public Health.2

Epidemiology studies the patterns of disease occurrence in human populations and the factors that influence these patterns. The term is obviously related to epidemic (derived from the Greek word meaning “upon the people”). An epidemic is an increase in the frequency of a disease above the usual and expected rate, which is called the endemic rate. Thus, epidemiologists count cases of a disease, and ask who, when, and where questions: Who is getting the disease? Where and when is the disease occurring? From this information, they can often make informed guesses as to why it is occurring. Their ultimate goal is to use this knowledge to control and prevent the spread of disease. The science of epidemiology is examined in more detail elsewhere. This chapter aims to give a more intuitive sense of what epidemiology is and does.

How Epidemiology Works

The first example of the use of epidemiology to study and control a disease occurred in London between 1853 and 1854, and it stands as an illustration of what epidemiology is and how it works. It was conducted by a British physician, John Snow, who is known as the father of modern epidemiology.

Snow was concerned about a cholera epidemic that had struck London in 1848. He noticed that death rates were especially high in parts of the city with water supplied by two private companies, both of which drew water from the Thames River at a point heavily polluted with sewage. Between 1849 and 1854, the Lambeth Company changed its source to an area of the Thames that was free of pollution from London’s sewers. Snow noticed that the number of cholera deaths declined in the section of London supplied by the Lambeth Company, while there was no change in the sections supplied by the Southwark and Vauxhall Company. He formulated the hypothesis that cholera was spread by polluted drinking water.3

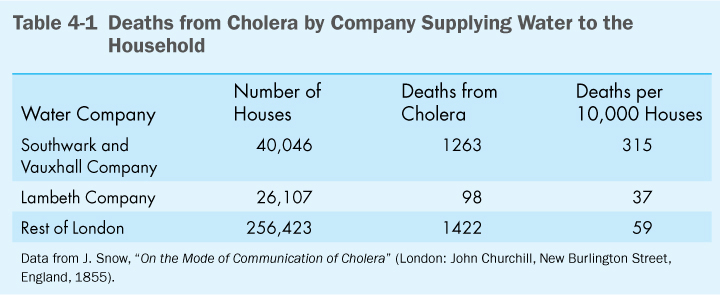

In 1853, there was a severe outbreak of cholera concentrated in the Broad Street area of London, in which some houses were supplied by one water company and some by the other. This provided an opportunity for Snow to test his hypothesis in a kind of “natural experiment,” in which “people of both sexes, of every age and occupation, and of every rank and station … were divided into two groups without their choice, and, in most cases, without their knowledge …”4(p.6–7) Snow went to each house in which someone had died of cholera between August 1853 and January 1854 to determine which company supplied the water. When he tabulated the results, he found that in 40,046 houses supplied by the Southwark and Vauxhall Company, there were 1263 deaths from cholera. By comparison, in 26,107 houses supplied by the Lambeth Company, only 98 deaths occurred. The rate of cholera deaths was thus 8.5 times higher in houses supplied by the Southwark and Vauxhall Company than those supplied by the Lambeth Company. This was convincing evidence that deaths from cholera were linked with the source of water (see Table 4-1).

Snow would not have been able to test his hypothesis without the data on cholera deaths, which had been collected by the British government as part of a system for routine compilation of births and deaths, including cause of death, since 1839. Now, the governments of all developed countries collect data on births, deaths, and other vital statistics. These data are often used for epidemiologic studies.

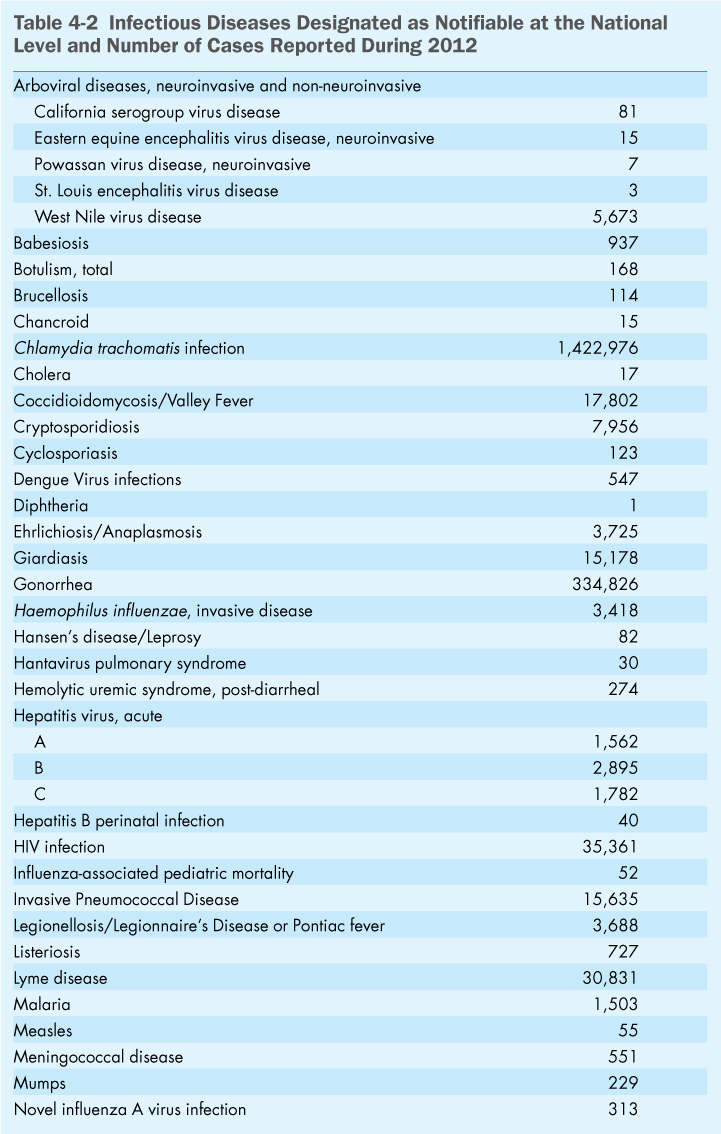

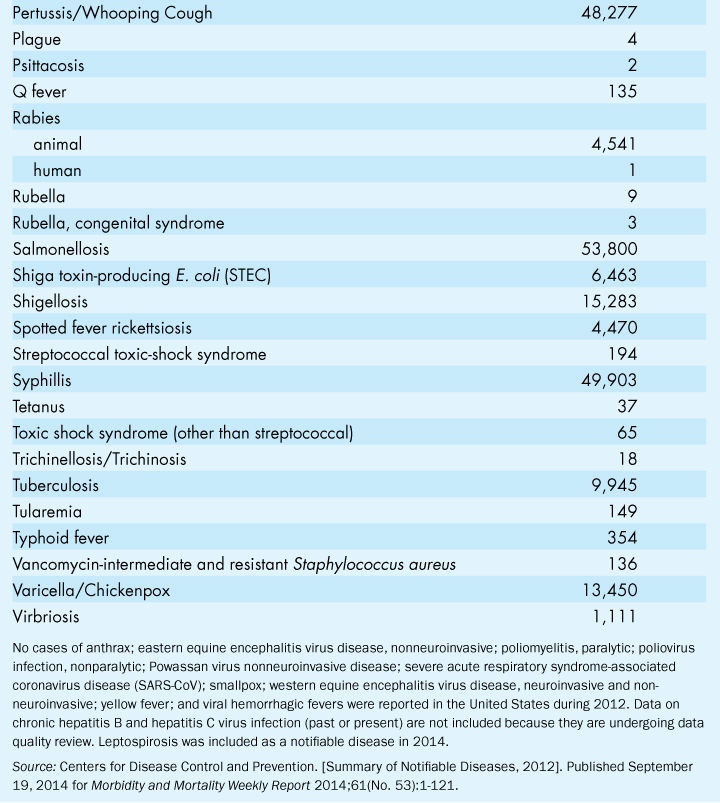

Because it is preferable to recognize that an epidemic is occurring before many people start dying, governments also use a system called epidemiologic surveillance, requiring that certain “notifiable” diseases be reported as soon as they are diagnosed. These are usually infectious diseases whose spread can be prevented if the appropriate actions are taken. In the United States, approximately 60 diseases have been identified by law as notifiable at the federal level, including, for example, tuberculosis, hepatitis, measles, and syphilis. Some states require reporting of additional infectious diseases. There may also be requirements for reporting birth defects, cancer, and other noninfectious conditions. All physicians, hospitals, and clinical laboratories must report any case of a notifiable disease or condition to their local health department, which in turn reports to the state health department and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The timely reporting of cases of notifiable diseases allows public health authorities to detect an emerging epidemic at an early stage. Measures can then be taken to control the spread of infectious diseases, as discussed later in this chapter. Reporting of chronic diseases is less widespread, but some public health agencies have urged a system to monitor conditions such as birth defects, Alzheimer’s disease, asthma, and a variety of cancers.5 Such a system would help to identify causes of these diseases, including environmental causes that could be controlled or eliminated, preventing further harmful effects.

While the surveillance system was created to control the spread of known diseases, the established network of reporting can facilitate the recognition that a new disease may be emerging. The first step in recognizing that a community is facing a new problem is usually a report to the local or state health department or the CDC by a perceptive physician who notices something unusual that he or she thinks should be investigated further. This is how AIDS came to be recognized early in the epidemic.

A Typical Epidemiologic Investigation—Outbreak of Hepatitis

Hepatitis A is a notifiable disease in all 50 states. Because it is caused by a virus that contaminates food or water, it is important to identify the source of any outbreak so that wider exposure to the virus can be prevented. Although hepatitis is not usually fatal to basically healthy people, it can make people quite sick for several weeks and can sometimes require hospitalization.

Because hepatitis is a notifiable disease, the local public health department is able to recognize when an outbreak occurs. A county may normally record only a few cases of hepatitis each year. This is the endemic level, the background level in a population. A sudden increase in the number of cases signifies an epidemic and calls for an epidemiologic investigation to determine why it is occurring.

The investigation requires asking the who, where, and when questions. This kind of medical detective work is nicknamed “shoeleather epidemiology.” The investigator starts with the reported cases—the who—although other, unreported cases may turn up once the investigator starts asking questions. Each victim must be interviewed and asked the when question: On what date did the first symptoms appear? Knowing that hepatitis has an incubation period of about 30 days, it is possible to work back to an estimated date of exposure. The where question is the hardest: Where did the victims obtain their food and water during the period of likely exposure and what sources did they have in common?

It may be that they all had eaten at the same restaurant. The epidemiologist would visit the restaurant and might find that the chef had developed hepatitis about a month earlier and been hospitalized; so the contamination of the food had stopped, and the epidemic would also stop. Alternatively, the chef may have had only a mild, perhaps unrecognized case and continued to work, thereby continuing to spread the infection. The health department might have to close the restaurant down, if necessary, until the chef is declared healthy.

Such investigations are a frequent task of epidemiologists at local health departments. A large number of these investigations deal with food poisoning outbreaks caused by contamination with Salmonella or Shigella, bacteria that commonly infect carelessly prepared or preserved food, both of which cause notifiable diseases. The Milwaukee cryptosporidiosis outbreak was solved by such an epidemiologic investigation. Although cryptosporidiosis was not a notifiable disease, the epidemic was recognized because it was so severe and widespread. If the disease had been notifiable, it might have been recognized and halted earlier. Cryptosporidiosis was added to the national list of notifiable diseases in 1995. (Table 4-2) gives a list of diseases that were reportable at the national level in 2012.

With some diseases, even a single case amounts to an epidemic. Measles, which is highly contagious, is preventable by vaccination. Although measles immunization for children was required by all states beginning in the 1970s, a number of measles epidemics occurred between 1989 and 1991 on college campuses. A reported case triggered a need for mass immunizations on campus. When epidemiologists found that many of the affected students had been immunized as infants, they concluded that a second vaccination was necessary for older children. The new policy put a halt to measles epidemics on campuses. However, in recent years, parental resistance to immunization has led to several outbreaks of this still dangerous disease, as discussed elsewhere in this book.

Since the bioterror attacks in the fall of 2001, the CDC has added to the list of notifiable diseases several infectious diseases caused by potential agents of bioterrorism. The first sign of a bioterror attack could be the report of a single case identified in a hospital emergency room.

Legionnaires’ Disease

In July 1976, the American Legion held a 4-day convention in Philadelphia. Before the event was over, conventioneers began falling ill with symptoms of fever, muscle aches, and pneumonia. By early August, 150 cases of the disease and 20 deaths had been reported to the Pennsylvania Department of Health, and the CDC was called in to help determine what was causing the epidemic. The investigation determined that the site of exposure was most likely the Hotel Bellevue-Stratford, one of four Philadelphia hotels where convention activities were held.6,7 Delegates who stayed at the Bellevue-Stratford had a higher rate of illness than those who stayed at other hotels, and many of those who fell ill had attended receptions in the hotel’s hospitality suites. However, cases also occurred in people who had only been near, not in, the hotel, suggesting that exposure could have occurred on the streets or sidewalks nearby. The evidence suggested that the causative agent was airborne, but it did not appear to spread person-to-person to the patients’ families.

While the epidemiologists were conducting their investigation, they enlisted the help of the CDC’s biomedical scientists to look for evidence of viruses or bacteria in the body tissues of the victims. They also considered the possibility of a toxic chemical, but no evidence of a cause could be found. It was not until the following January that the biomedical scientists found the bacteria that were responsible for the epidemic, which by then was called Legionnaires’ disease. The hotel was searched for the source of the bacteria. It was eventually found in the water of a cooling tower used for air conditioning. Legionella bacteria had been pumped into the cooled air and inhaled by the victims.

Once the Legionella bacteria were identified, they were found to be responsible for a number of other outbreaks of pneumonia around the country. The bacteria were also identified in preserved blood and tissue samples collected in 1965 from victims of a previously unsolved outbreak of pneumonia which affected some 80 patients at St. Elizabeth’s psychiatric hospital in Washington, DC, killing 14 of them.7 Thus Legionnaires’ disease had probably been around but had gone unrecognized as a specific disease at least since the invention of air conditioning. Federal air-conditioning standards were changed after the Philadelphia epidemic; stringent requirements for cleaning of cooling towers and large-scale air-conditioning systems were introduced. Outbreaks still occur, including one in the Bronx, New York, during the summer of 2015.8 Because legionellosis is now a notifiable disease, outbreaks are recognized and control measures implemented more rapidly.

Eosinophilia-Myalgia Syndrome

Although infectious agents are usually suspected first in any outbreak of a new disease, epidemiologists must also consider exposure to a toxic substance as an alternative cause. Physicians and epidemiologists found this to be the case in a puzzling outbreak first reported in New Mexico. In October 1989, several Santa Fe doctors were comparing notes on three patients suffering from a novel condition involving fatigue, debilitating muscle pain, rashes, and shortness of breath. Blood tests on all three had revealed very high counts of white blood cells called eosinophils. The doctors knew of no known condition that could explain these findings. However, they were struck by the fact that all three patients, when questioned about drugs or medications they were taking, had mentioned a health food supplement called L-tryptophan. L-tryptophan is a “natural” substance, a component of proteins, that had been publicized as a treatment for insomnia, depression, and premenstrual symptoms. Believing that more than coincidence was involved in these three cases, the doctors reported them to the New Mexico State Health Department.9

The Health Department reported the cases to the CDC and began an investigation to determine whether additional cases existed and whether there was a consistent link with L-tryptophan. By searching the records of clinical laboratories in Santa Fe, Albuquerque, and Los Alamos, they discovered 12 additional patients whose blood had exhibited high white-cell counts since May 1. A team of health department investigators interviewed these 12 people and found that they all had used L-tryptophan. They also interviewed 24 people of the same age and sex as the patients who lived in the same neighborhoods—a control group—and found that only two had taken the supplement. This strongly suggested that there was a link between L-tryptophan exposure and the illness. The CDC notified other state health departments, which conducted their own investigations, and by November 16 the CDC received reports from 35 states of 243 possible cases of the new disease, called eosinophilia-myalgia syndrome (EMS). On November 17, the Food and Drug Administration announced a nationwide recall of products containing L-tryptophan. The publicity brought forth a flood of new reports of the syndrome, but then new cases began to drop off. By August 1, 1992, 1511 cases had been reported by all 50 states. Many patients were left with permanent disabilities and 38 people had died, but the epidemic was over.10

Why had this natural substance caused such severe consequences? L-tryptophan is an amino acid, present in many foods including meat, fish, poultry, and cheese. It is also added to infant formulas, special dietary foods, and intravenous and oral solutions administered to patients with special medical needs. No cases of EMS had been reported from these products. Tests on the recalled tablets indicated that a toxic contaminant, formed as a result of a recent change in one factory’s method of production, may have been responsible for the epidemic of 1989. However, there is evidence that earlier, unrecognized cases had occurred since the product was introduced in 1974.11 The fact that many people took the supplements with no apparent harm suggests that individual variations in susceptibility may exist.

Serious outbreaks of illness caused by toxic contamination of food, through production errors or outright fraud, have occurred a number of times over the past few decades. It is usually epidemiologists who identify the source of the problem. To many public health experts, the EMS epidemic of 1989 resembled an illness with similar symptoms that affected some 20,000 people in Spain in 1981, killing more than 300 of them within a few months. An infectious agent had first been suspected, but epidemiologists noted an odd geographical distribution of the outbreak. Patients lived either in a localized area south of Madrid or in a corridor along a road north of the city. The epidemiologists found that the affected households had bought oil for cooking from itinerant salespeople, who were illegally selling oil that had been manufactured for industrial use.12 Laboratory scientists investigating the nature of the contaminants and how they might have caused the symptoms have not specifically identified a single chemical as being responsible. They now suspect that a range of chemicals, even at very low concentrations, may induce autoimmune responses in susceptible people, causing the body’s immune system to attack its own tissues. Such outbreaks caused by toxic contamination of foods and drugs may be much more common than is generally recognized.13 In the cases of toxic oil syndrome and EMS, government action to remove the contaminated product put an end to the epidemic. However, survivors still suffer from symptoms.

Epidemiologic surveillance is a major line of defense in protecting the public against disease. It is the warning system that alerts the community that something is wrong, that a gap has opened in the protective bulwark against preventable disease or that a new disease has appeared on the horizon. The sooner the surveillance system kicks in, the sooner action can be taken to stop the epidemic. Before the health department is notified, individual doctors are trying to cure individual patients, often unaware that the problem is more widespread. After the epidemic is recognized, all the resources of the community—local, state, or national—can be mobilized to prevent the disease’s spread. Whether it uses vaccination campaigns against measles, isolation of hepatitis-infected food workers, new regulations on air conditioning systems, or recall of contaminated food or drugs, the government must act to protect the health of the public. Epidemiologic surveillance has become even more important as concerns about bioterrorism have increased.

Epidemiology and the Causes of Chronic Disease

Epidemiology has had a different role to play in investigating the causes of the diseases common in older age, such as cancer and heart disease, which are quite different from infectious diseases or acute poisoning. Until the mid-20th century, these conditions were thought of as a natural part of aging, and no one thought to look for causes or tried to prevent them.

Cancer, heart disease, and other diseases of aging do not have single causes. They tend to develop over a period of time, are often chronic and disabling rather than rapidly fatal, and cannot be prevented or cured by any vaccine or “magic bullet.” The best hope for protecting the public against these diseases is to learn how to prevent them, or at least how to delay their onset. Prevention, however, requires an understanding of the cause or causes of a disease and the factors that influence how it progresses. Epidemiology has made major contributions to the current understanding of the causes of heart disease and some cancers and what can be done to prevent them. Epidemiologic studies will continue to yield information on how people can protect themselves against cancer, Alzheimer’s disease, and other afflictions of aging.

Epidemiologic studies of these chronic diseases are much more complicated and difficult than investigations of acute outbreaks of infectious diseases or toxic contamination. Except for the clear link between smoking and lung cancer (discussed later in this chapter), most chronic diseases cannot be attributed to a single cause. There may be many different factors that play a part in causing a disease, factors that epidemiologists call “risk factors.” The long period over which these diseases develop also contributes to the difficulty of determining the causative factors. Epidemiologists must determine which of a person’s many experiences over the previous decades are relevant, and what significant exposures might have occurred 10 or 20 years ago that may have increased the person’s risk of developing the disease today.

Epidemiology has developed a number of methods to study chronic diseases and to try to answer the difficult questions. This chapter describes a few of the best-known studies that have had major impacts on understanding the causes of heart disease and cancer.

Heart Disease

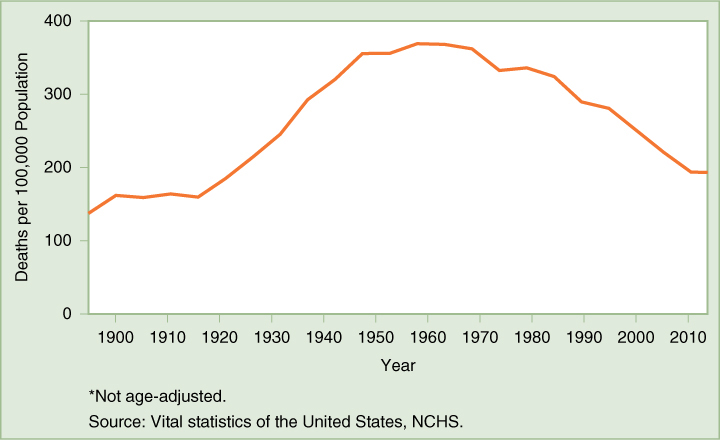

Since the 1920s, when infectious disease mortality had dropped to approximately its current low levels, heart disease has been the leading cause of death in the United States for both men and women. Deaths from heart disease increased dramatically during the first half of the 20th century, as seen in (FIGURE 4-1). After World War II, one in every five men was affected with heart disease before the age of 60, and little was known about why. In 1948, an epidemiologic study was launched in Framingham, Massachusetts, to investigate factors that might be causing the problem. It was the first major epidemiologic study of a chronic disease. More than half of the middle-aged population of the town, more than 5000 healthy people, were examined, and data were recorded on their weight, blood pressure, smoking habits, the results of various blood tests, and other characteristics. Two years later, the same people were examined again, and these tests have been and continue to be repeated every two years for the rest of their lives.14