Endovascular Treatment of Varicose Veins

Julianne Stoughton

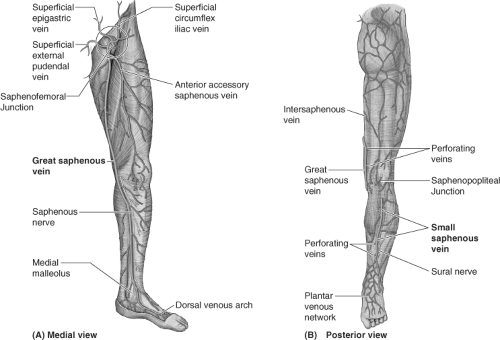

Varicose veins are primarily the result of ambulatory venous hypertension in the superficial venous system. Successful management depends upon an intimate knowledge of the highly variable anatomy of the venous system of the lower extremity. In general, the deep veins exist within the muscular compartment of the lower extremity. The superficial veins are positioned outside of the muscular fascia and consist of axial veins (great saphenous, accessory saphenous, small saphenous veins [SSVs]) and their tributaries. The perforator veins connect the superficial and deep venous system in numerous locations. The use of noninvasive duplex ultrasound has revolutionized the evaluation of a patient’s specific anatomy, allowing the surgeon to choose the appropriate treatment options. Specific information such as diameter, depth, length, and a description of refluxing vein segments helps the clinician decide whether the veins should be treated by surgical means, or by using endovascular techniques.

Deep and Perforating Veins

Deep veins are emptied against gravity with muscular contraction, relying upon unidirectional valves and an open proximal system. Perforator veins, varied in location, also have unidirectional valves which facilitate the return of blood to the deep system with muscular contraction. If the valves are incompetent and the perforator is excessively enlarged, the perforator veins may become a clinically significant source of reflux. Perforators can also be enlarged due to a re-entry phenomenon, and may recover following procedures treating superficial venous insufficiency alone. Clinically important perforators often connect the posterior saphenous system in the calf to the posterior tibial veins in the medial calf and ankle (previously “Cockett” perforators). Other common locations for perforators include the medial thigh (communicating with the femoral vein), the popliteal fossa (connecting with the popliteal vein), or even in the lateral leg. Nomenclature for perforator veins has moved away from the standard eponyms to a more specific characterization of location and distance from a particular landmark (i.e., paratibial perforator, 20 cm above the medial malleolus).

Great Saphenous Veins (Gsvs)

Superficial veins connect to the deep system via the axial vein trunks, and are variable in length and location. The saphenofemoral junction (SFJ) is usually found just at, or below, the inguinal ligament, and just medial to the femoral artery. The main great saphenous vein (GSV) begins at the medial malleolus of the ankle, is often duplicate in the calf and joins just below the knee, travels up the medial thigh, and extends to the saphenofemoral vein junction (SFJ) in the groin. Many variations of accessory saphenous veins exist including the anterior accessory saphenous and posterior accessory saphenous veins. These accessory saphenous veins can reflux concurrently, or they can become sources of recurrent varicosities after treatment of the GSV.

Small Saphenous Veins (Ssvs)

In the posterior calf, the SSV begins at the lateral aspect of the foot, continues over the Achilles tendon, up the posterior calf to the saphenopopliteal junction (SPJ). The anatomy of the SSV is highly variable, and commonly duplicate, yet the location of the SPJ is typically within 10 cm of the popliteal fossa. A cranial extension, or posterior thigh extension (PTE), can continue from the SSV up into the posterior thigh emptying into the femoral vein. The “intersaphenous vein” can communicate from the SSV in the popliteal fossa up into the medial thigh GSV—this was previously described as the vein of Giacomini (Fig. 1). Refluxing perforators are found in the popliteal fossa, often

lateral and superior to the SPJ, which must be carefully distinguished from SSV reflux. Gastrocnemius and Soleal muscular veins are deep to the muscular fascia, yet can be mistaken for the SSV by inexperienced technicians.

lateral and superior to the SPJ, which must be carefully distinguished from SSV reflux. Gastrocnemius and Soleal muscular veins are deep to the muscular fascia, yet can be mistaken for the SSV by inexperienced technicians.

The saphenous veins are identified within their own fascial envelope, outside the muscular fascia, and beneath the saphenous fascia. The administration of tumescent anesthesia is facilitated by injecting into this saphenous compartment.

Superficial Tributaries

Tributaries consist of an interconnecting network of subcutaneous veins, attaching to and communicating between the main saphenous trunks. There are several “zones of influence” which are clinically apparent when evaluating a patient with varicose veins. The ultrasound evaluation is dependent upon the sonographer’s knowledge of venous anatomy which will direct the exam to the clinically important sites of reflux. Ultrasound evaluation can be used to evaluate direction of flow, diameter, length, valve closure time, and description of whether the tributaries (varicosities) are associated with refluxing axial veins or enlarged incompetent perforators.

Proximal Pelvic Veins

The existence of medial labial and thigh varicosities might prompt further evaluation more proximally searching for pelvic venous insufficiency. Abdominal wall and suprapubic varicosities must also be noted on careful physical exam in the upright position; these can signify a more proximal source of obstruction. Varicosities in these areas should not be treated without a full understanding of the more proximal iliac and venacaval anatomy which is best assessed by CTV, MRV, or intravenous ultrasound (IVUS).

Smaller Veins

Reticular veins are flat, blue, and <3 mm; and spider veins are the more superficial, <1 mm, red or purple dermal veins. These veins are amenable to cosmetic sclerotherapy which will not be discussed within the scope of this chapter. Corona phlebectasia condition is associated with a flare or confluence of spider veins at the medial ankle and foot, and can be a sign of deep or perforator vein insufficiency and may prompt a more thorough evaluation with duplex examination (Fig. 2).

Scoring Systems

Venous disease is a progressive, usually hereditary condition, which often begins just after puberty and progresses with advancing age. CEAP, a classification system of venous disease, has been created in order to better define the specific type and stage of venous insufficiency. It has four components including: Clinical (Stages 1 to 6; Figs. 3 to 8), Etiology (primary or secondary), Anatomic (deep, superficial, or perforator), and Pathophysiology (reflux, obstruction, or both). Another scoring system which has gained popularity is the Venous Clinical Severity Score (VCSS) which assigns a score to various clinical attributes such as pain, varicose veins, edema, skin changes, use of compression, and ulceration. This scoring system can be helpful in evaluating outcomes, and following patients for progression.

Symptoms

In the early stages of venous disease, there are mild symptoms including aching, fatigue, heaviness, or throbbing while upright. Conservative measures including support hose at 20 to 30 mm Hg, or 30 to 40 mm Hg will often help control the early symptoms. As the degree of venous hypertension increases, the enlarging varicosities can cause some local discomfort. Pain, cramping, or restless leg symptoms at night might be multifactorial, but can be associated with venous disease and may improve with treatment of the venous hypertension. Itching can be associated with mast cell degranulation, also usually relieved by eliminating the sources of reflux. Neurologic symptoms such as numbness and sharp or radiating pain are not likely attributed to venous insufficiency.

Acute change in symptoms of pain, swelling, discoloration should be evaluated on a more urgent basis with a venous duplex scan in order to rule out superficial or deep vein thrombosis (DVT). Superficial phlebitis (SVT) is usually characterized by areas of tenderness, erythema, warmth, and often palpable cords in areas of varicosities. SVT should also be evaluated by venous duplex in order to assess the saphenous trunks and deep veins. SVT of tributaries is treated symptomatically with NSAID’s, compression, and warm compresses which can lead to prompt relief of symptoms. Thrombosis involving the saphenous vein trunks should be treated more aggressively and followed closely for signs of progression.

Physical Findings

Progressive enlargement of varicosities can often be noted without many symptoms (C2). Eventually leg edema (C3) will ensue

which will lead to progressive skin changes if the ambulatory venous hypertension is not addressed. Edema of the leg is not always venous in origin. Other causes of leg swelling must be considered including, but not limited to, lymphedema, lipedema, medication effects, pulmonary, cardiac, renal, hepatic, endocrine, and sleep apnea. In patients with advanced CEAP classification and significant edema, a high index of suspicion is advisable to rule out more proximal obstruction prior to treatment of superficial venous insufficiency.

which will lead to progressive skin changes if the ambulatory venous hypertension is not addressed. Edema of the leg is not always venous in origin. Other causes of leg swelling must be considered including, but not limited to, lymphedema, lipedema, medication effects, pulmonary, cardiac, renal, hepatic, endocrine, and sleep apnea. In patients with advanced CEAP classification and significant edema, a high index of suspicion is advisable to rule out more proximal obstruction prior to treatment of superficial venous insufficiency.

Fig. 6. C4 disease: Varicosities with associated skin changes (C4a: eczema, pigmentation; and C4b: lipodermatosclerosis, atrophie blanche). |

Venous stasis changes in the skin (C4) usually occur in the gaiter distribution; they involve pigmentation, lipodermatosclerosis, inflammation, and eventual ulceration (C6). These advanced changes of chronic venous disease are often associated with multiple sources of reflux with or without obstruction. Etiology of ulceration must be defined by performing a thorough medical evaluation and arterial assessment.

Physical Exam

Patients with venous disease should be examined in the upright position in order to determine the extent and location of varicosities. The leg needs to be inspected visually,

palpated for phlebitic vein segments, and assessed for skin changes, ulceration, and edema. Note must be made whether the edema is pitting, and full pulse evaluation should be performed. Assessment for masses, aneurysms, and proximal abdominal, suprapubic, or labial varicosities should also be performed.

palpated for phlebitic vein segments, and assessed for skin changes, ulceration, and edema. Note must be made whether the edema is pitting, and full pulse evaluation should be performed. Assessment for masses, aneurysms, and proximal abdominal, suprapubic, or labial varicosities should also be performed.

Noninvasive Evaluation Superficial Veins

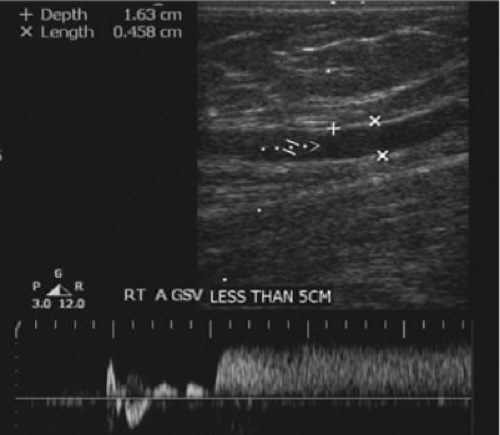

Duplex evaluation of the superficial venous system should also be done in the upright position. In addition to the routine evaluations of axial and deep veins, the exam should be directed by physical exam of the varicosities or skin changes. All veins should be evaluated in B mode for compressibility, wall thickness, and presence of internal echoes. Axial veins should be described with regard to diameters, depths, lengths (within the fascia), degree of tortuosity, and communication with perforators or other enlarged tributaries. Perforators are assessed for diameters at the fascia level and the direction of flow. Using color flow doppler, the presence of reflux with augmentation and release and the locations of refluxing veins must be carefully recorded. Patients should be in the standing or tilt table position (Fig. 9), non-weight bearing on the leg being examined. Perforators are best evaluated with the leg in the dependent position with full relaxation of the muscles. Distal compression cuffs or hand squeeze should be employed to evaluate each source of reflux with waveform analysis. Valve closure times of >0.5 seconds are considered to be abnormal (Fig. 10).

Deep Veins

Deep system should be fully evaluated for compressibility in order to rule out DVT or obstruction. Waveform analysis should be performed at each level to evaluate for reflux after distal compression and rapid release, and valve closure times should be typically <0.5 to 1 second. Careful, bilateral evaluation of respiratory phasicity in the groin can help rule out more proximal iliac or vena caval obstruction. Continuous flow pattern in either groin implies proximal obstruction which should be further investigated.

Proximal Obstruction

If there is any clinical suspicion of concomitant proximal venous obstruction or reflux, the ileo-caval venous system should be evaluated prior to any superficial venous treatments. If the index of suspicion is high, venogram can be obtained allowing appropriate treatment if needed. Patients with low or moderate risk of proximal obstruction could be evaluated preoperatively with MRV or CTV. Newer approaches involving IVUS have proved successful in diagnosing iliac obstruction, and have been done preoperatively, or via the saphenous vein access at the time of endovenous ablation.

Deep Vein Thrombosis

DVT is a condition which can be acute or chronic. Current guidelines have become more aggressive with regard to early intervention and restoration of flow for proximal deep venous thromboses. The treatment of these more proximal issues will be discussed in other chapters. Femoral and popliteal vein DVT can be treated with routine anticoagulation, yet recent approaches are becoming more aggressive in restoring flow whenever possible in order to further prevent post-thrombotic syndrome. Distal calf vein thrombosis remains controversial with regard to treatment at this time. Some argue that only aggressive or unprovoked calf vein DVT should be treated. Controlled trials and venous registries are attempting to answer these questions.

Superficial Vein Thrombosis

Superficial venous thrombosis (SVT) can occur in enlarged tributaries or within the saphenous vein trunks, the later being a more concerning condition. Prompt recognition is important in order to prevent progression, and a search for underlying cause should be undertaken. Virchow’s triad of intimal injury, stasis, and hypercoaguability can lead to the formation of a thrombus, and recurrences in a similar location are likely if not treated appropriately. In general, SVT should be evaluated with venous duplex scanning in order to rule out axial vein involvement or DVT. If it only involves the tributary veins, compression, NSAIDs, and warm compresses usually suffice to relieve the acute symptoms, and the surgical intervention should be delayed until after the acute event has resolved. Axial vein SVT can be a more aggressive entity, especially if it is above the knee. Serial duplex evaluation, a thrombophilic workup, and a search for malignancy should be undertaken in those unprovoked cases. Many practitioners treat with a course of low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) if the thrombus is close to the SFJ or appears to be propagating. SFJ ligation should be done only in those patients with acute thrombus extending into the SFJ with a contraindication to anticoagulation. Surgical or endovascular interventions should be delayed if possible until the thrombus has become chronic or has recanalized. Repeat duplex evaluation must be performed in order to determine the degree of recanalization and reflux after several months. Subsequent treatment can be tailored to reduce the risk of progression of venous disease and recurrent thrombosis. If the recanalization is partial, a combination of thermal and chemical ablation techniques can be employed to close the recanalized refluxing vein.

Deep Venous Obstruction and Reflux

Commonly a combination of deep venous obstruction and reflux can be found in patients with advanced venous disease. In cases of deep venous insufficiency and proximal venous obstruction, the obstruction should be addressed first, which may partially correct the deep venous reflux. There are currently trials involving implantable deep venous valves which are addressed in other chapters.

If there is concomitant reflux in the deep and superficial systems, the superficial venous insufficiency should be corrected first. A majority of patients with both deep and superficial reflux have an improvement in the deep system following saphenous or perforator vein ablation.

Superficial Reflux

Patients with superficial venous insufficiency are the most commonly encountered and have the widest variety of treatment options available to them. Treatment should always begin with conservative measures including compression therapy, exercise, weight loss, and intermittent elevation. Those patients who continue to have signs or symptoms of progressive venous insufficiency should be evaluated with duplex scanning. Some patients can be managed conservatively if they have minimal symptoms or if are not showing signs of progression. Patients with CEAP Class 2 to 6 venous disease are usually candidates for treatment.

Varicose veins, although often quite large, can have a varying degree of symptomatology and are often associated with one or multiple sources of reflux. Upon careful history and physical exam, one can determine that they are symptomatic and progressive. Edema, if venous in origin, is another indication for treatment of venous insufficiency. The edema should be managed by eliminating sources of superficial reflux and continued emphasis on conservative compression therapy.

Ulceration

Ulceration should be managed with conservative measures, for example, compression, wound care, and an attempt at healing should precede other treatments if possible. Treatment should be performed to reduce the ambulatory venous hypertension when conservative measures have failed or once ulcers have healed. Because studies have shown decreased ulcer recurrence with surgical stripping of the GSV, it is presumed that endovascular ablation would accomplish a similar benefit. Patients with advanced venous disease, C5 to 6 healed or active ulceration, often have multiple sources of reflux including axial veins as well as perforator or deep venous reflux. In patients with medial leg ulcers, if the GSV is refluxing along its entire length, attempts should be made to ablate the longest segment possible. If the ulcer exists on the lateral aspect of the ankle or foot, careful evaluation should be made of the SSV in the posterior calf. Timing and choice of treatments should be tailored to the patient’s clinical status and the duplex findings.

Generally speaking, endovascular techniques are favored both by the patient and clinician. Becoming the standard of care, advantages include the avoidance of general or sedation anesthesia, the minimal risk of wound issues, earlier ambulation and return to usual activities, and lower risk of long-term neovascularization and recurrence. Patient satisfaction is also a motivating issue, and has driven these techniques to the forefront. In summary, the less invasive techniques should be performed whenever possible.

Conservative Management

Conservative therapy should be instituted when first evaluating patients with venous disease prior to any surgical intervention. A follow-up evaluation should then be completed to ascertain whether these measures have been sufficient in eliminating symptoms or signs of progression. These conservative measures should be adopted as a lifelong measure to help prevent other sources of reflux and progression of venous disease. Recent studies are evaluating alternative phlebotonic compounds, including horse chestnut seed extract (aescin) or Diosmin (flavonoid), yet their benefits have been modest, and not as helpful when compared to compression alone. Continued use of compression therapy, weight control, exercise, and intermittent elevation are stressed to all patients before and after the procedures.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree