Endovascular Procedures for Aorto-Iliac Occlusive Disease

Vikram S. Kashyap

Tara Mastracci

Extensive aorto-iliac occlusive disease (AIOD) often results in debilitating symptoms. Most commonly, these patients present with claudication. Limb-threatening symptoms occur in the setting of multilevel occlusive disease. This may manifest as rest pain or ulceration. The treatment of AIOD remains gratifying for the patient and surgeon. Often, operative or endovascular treatment results in rapid symptom abatement, clearly discernible hemodynamic changes, and durable prevention of recurrent symptoms.

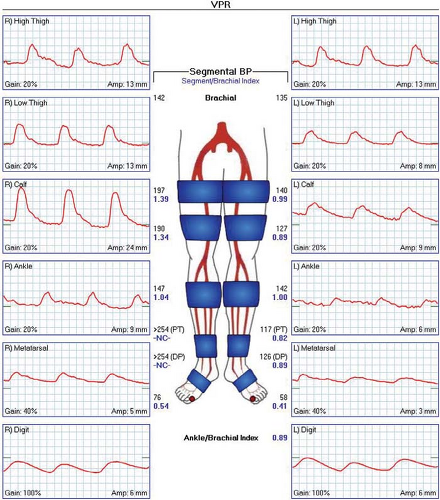

Preoperative evaluation of limbs of patients with peripheral vascular disease starts with careful physical examination. Patients with AIOD will have absent or faint femoral pulses. Calcification in the femoral region can also be appreciated in thin patients. Pedal pulses are usually absent and ulceration or gangrene may result from concomitant infrainguinal occlusions. Noninvasive vascular laboratory imaging with either segmental pressures/pulse volume recordings (PVRs) (Fig. 1) or duplex examination is helpful in determining the level and degree of disease present. In the setting of AIOD, high-thigh segmental pressures and waveforms will be diminished. In unilateral disease, a horizontal gradient will be present. The presence of diabetes, renal disease, or a long history of smoking may lead to significant calcification in the iliac and femoral vessels causing noncompressibility and false elevation of the pressures. In these cases, PVR assessment and toe-brachial indices are more sensitive. We choose additional imaging with workup with computed tomographic angiography (CTA). This allows

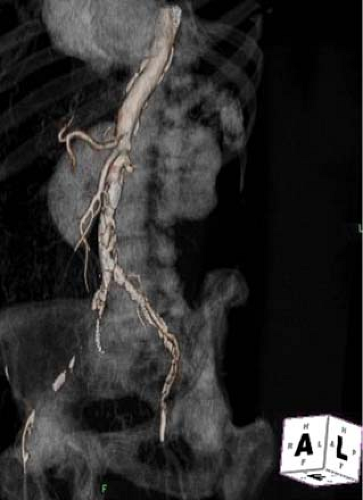

cross-sectional imaging, as well as three-dimensional reconstruction to assist in the planning of treatment in patients with extensive AIOD (Fig. 2). CTA is very helpful in determining the extent of AOID, the degree of calcification, and the rare presence of aortic occlusion secondary to a thrombosed abdominal aortic aneurysm. Endovascular therapy may be precluded in the last situation and in cases of circumferential calcification making plaque fracture by angioplasty difficult without arterial rupture.

cross-sectional imaging, as well as three-dimensional reconstruction to assist in the planning of treatment in patients with extensive AIOD (Fig. 2). CTA is very helpful in determining the extent of AOID, the degree of calcification, and the rare presence of aortic occlusion secondary to a thrombosed abdominal aortic aneurysm. Endovascular therapy may be precluded in the last situation and in cases of circumferential calcification making plaque fracture by angioplasty difficult without arterial rupture.

Severe AIOD has been treated via open vascular reconstruction using aortobifemoral bypass (ABF) in current vascular surgical practice. However, iliac stenoses are preferentially treated via endovascular means with high technical success rates and low morbidity. These endovascular cases are usually straightforward and lead to durable patency. Endovascular procedures in the proximal iliac arterial beds appear to have greater durability than endovascular treatment of the infrainguinal arteries presumably because of larger arterial size and flow. As endovascular therapies have evolved, this has been mirrored by a decreasing number of patients undergoing ABF. Treatment of aorto-iliac occlusions remains a more challenging endovascular treatment modality than the treatment of iliac stenoses.

The goals of the Trans-Atlantic Inter Society Consensus (TASC) statement on treatment of peripheral arterial disease (PAD) in 2000 (and updated in 2007) were to organize and review the available literature to identify patients with PAD, and help determine the best treatment for patients with disease at different levels, and effecting various territories. The framework allowed stratification of atherosclerotic lesions by length and morphology. According to the TASC definitions for iliac occlusive disease, short focal iliac stenosis are classified as TASC-A. Iliac occlusions can be stratified as B, C, and D lesions. TASC-B lesions include unilateral common iliac occlusions only. TASC-C iliac lesions include unilateral external iliac occlusions not extending into the common femoral artery, or bilateral common iliac occlusions. TASC-D lesions are bilateral external iliac occlusions or ipsilateral common and external iliac occlusions or diffuse disease of the aorta and both iliac arteries. Endovascular procedures are thought to be the treatment of choice for type A lesions (stenoses <3 cm only) and open surgical therapy the procedure of choice for type D lesions. According to the TASC statement, more evidence is needed for type B and C lesions with a preference for endovascular methods for the former and surgical methods for the latter. This consensus statement reinforced the concept of treating short, focal stenoses via endovascular means and using surgical revascularization for long-segment occlusions based on the available data at that time.

We believe that endovascular therapies can be used as first-line therapy for AIOD, irrespective of TASC classification. This is based on improved catheter-directed techniques allowing recanalization and new angioplasty and stent designs. In addition, there is an increasing capability of vascular specialists in treating more complex disease with catheter-based methods. Lastly, we preferentially use endovascular procedures because operative options are not lost, even if the endovascular therapy is unsuccessful. In our elderly patients with severe comorbidities, a minimally invasive option for revascularization leads to decreased morbidity and length of recovery.

Treatment of patients with PAD requires attention to the ravages of atherosclerosis on a systemic level, as well as to the burden of disease in their limbs. Risk factor modification can diminish the long-term effects of atherosclerosis on the cardiovascular system in these patients and ameliorate systemic comorbidities at the time of operative or endovascular treatment. Controlling blood sugar, serum cholesterol, blood pressure, and importantly smoking can lead to substantial short- and long-term benefits. In consultation with the patient’s medical physician, antihyperglycemic treatment, smoking cessation, lipid lowering therapy, and antihypertensive therapy are instituted for the appropriate risk factors. Antiplatelets are administered to all in the form of low-dose aspirin. Clopidogrel (Plavix) is usually instituted after endovascular therapy to prevent stent thrombosis at the dose of 75 mg/day for 3 months. Less common therapies, such as homocysteine-lowering therapy and antithrombotic therapy are considered. Patients with nondisabling claudication can be considered for supervised exercise programs, as well as cilostazol (Pletal, 100 mg BID) pharmacotherapy for at least 3 months. The importance of smoking cessation programs cannot be overemphasized. However, despite pharmacological and counseling interventions, recidivism remains disappointingly high.

Endovascular Technique

Isolated Aiod

Using endovascular techniques to treat chronic occlusive disease in the aorto-iliac segment requires a creative approach tailored to the lesion anatomy in an individual patient. The specific steps are access, recanalization, angioplasty, and then usually stenting. Each step requires specific skills and instrumentation. Experience with multiple means of access (i.e., femoral, brachial), a wide variety of guidewires and catheters and an operative environment that allows surgical exposure of arteries are critical. We believe an endovascular suite (hybrid operating room) allows the high-fidelity fluoroscopic imaging combined with operating room facilities to allow the safe and efficient performance of these procedures. This allows the combined (hybrid) open and endovascular surgery in some challenging scenarios where arterial pathology prohibits a purely endovascular approach. Attention must be paid to operative sterility and radiation exposure.

One critical clinical decision in planning for endovascular therapy for AIOD is whether a purely percutaneous procedure can be performed. If so, conscious sedation, rather than anesthesia, can be organized simplifying the logistics of the procedure. If femoral reconstruction is planned, regional or general anesthesia may be required.

In patients with occlusive disease of the aorto-iliac segments that does not extend into the common femoral arteries, a purely percutaneous procedure can be planned. Conscious sedation using short-acting opiates and anxiolytics are given. Access is usually performed with ultrasound guidance since the femoral pulses are either barely or not palpable. This is done with an anterior wall puncture only. Retrograde access to the iliac artery with less atherosclerotic burden allows catheter placement (Fig. 3A) and aortography. Subsequent imaging of the contralateral limb can be done via nonselective aortography (Fig. 3B) or selective catheterization using an “up and over technique.” Alternatively, brachial artery access can be the initial source of entry in cases with complete aortic occlusion, previous aortobifemoral graft, or heavily diseased femoral arteries. One must keep in mind that left brachial access does require a longer overall system, including long sheaths and catheters sometimes >100 cm. For diagnostic angiography, percutaneous access, the placement of a 5-French (Fr) sheath and eventual manual compression for hemostasis is common. However, if endovascular intervention is to be performed, larger sheaths (6–8 Fr) are often needed to accommodate delivery of the endoluminal devices and we often use a closure device at the completion of the procedure.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree