Endoscopic Pancreatic Debridement and Drainage

Udayakumar Navaneethan

Andres Gelrud

DEFINITION

Endoscopic pancreatic debridement is performed in patients with pancreatic necrosis, in particular, walled-off necrosis (WON).

Pancreatic necrosis is defined by the lack of enhancement of the pancreatic parenchyma on cross-sectional imaging after intravenous contrast administration.

Pancreatic necrosis is classified as acute necrotic collection and WON depending on the time course (4 weeks) of the diagnosis of pancreatitis and presence or lack of encapsulated wall, by the revised Atlanta classification.1

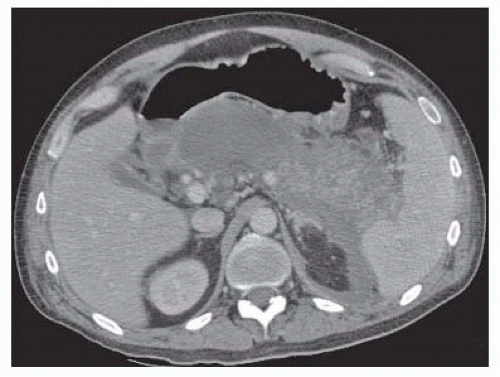

Acute necrotic collection is defined as a collection containing variable amounts of fluid and necrotic tissue involving the pancreatic parenchyma and/or the peripancreatic tissues occurring within the first 4 weeks of acute pancreatitis (FIG 1).1

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

It is important to distinguish WON from pseudocyst. Pseudocyst is a fluid collection in the pancreatic or peripancreatic tissue surrounded by a well-defined wall and contains no solid material. Diagnosis can be made usually on these morphologic criteria. Amylase activity is high if the pseudocyst fluid is aspirated. Disruption of the main pancreatic duct or its intrapancreatic branches without necrosis usually leads to pseudocyst formation.1

Cystic neoplasm of the pancreas such as an intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm or mucinous cystic neoplasm can mimic WON. A previous history of acute pancreatitis helps differentiate both conditions, and in occasion, fine needle aspiration (FNA) needs to be performed to better characterize the collection before endoscopic drainage.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Two-thirds of patients with pancreatic necrosis in the setting of necrotizing pancreatitis have sterile necrosis and can be managed conservatively without any intervention.2

Interventions performed in patients with sterile pancreatic necrosis can increase the risk of introduction of infection into the necrotic tissue, resulting in requirements for additional interventions and its associated morbidity and mortality.3

Sterile pancreatic necrosis requires drainage only in patients with symptoms. External mechanical obstruction of the biliary system (elevated liver enzymes with a dilated bile duct) or gastric outlet with symptoms of nausea, vomiting, early satiety, and inability to resume oral intake. Persistent, narcotic-requiring pain or recurrent acute pancreatitis are indications for drainage.4

However, the main role for endoscopic intervention is the presence, or suspicion, of infected necrosis with concomitant clinical deterioration.

Debridement should be delayed, if at all possible, until the necrosis is walled off and a well-defined capsule is present, which usually takes around 4 weeks. WON is a prerequisite for successful endoscopic therapy.4

The goal of therapy needs to be well defined and a multimodality approach (clinical pancreatologist, surgery, and interventional radiology) has a higher chance of success and should be considered. Surgical backup during endoscopic drainage is strongly recommended in case of complications at the time of endoscopic debridement.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

The morphologic features of acute pancreatitis and resultant complications are diagnosed by high-resolution multidetector contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) and can detect most local complications as reported in the revised Atlanta classification.1

The diagnosis of necrosis is based on imaging features of a heterogeneous collection with liquid and nonliquid density with varying degrees of loculations.

WON is defined based on the presence of necrosis with a well-formed wall and complete encapsulation.

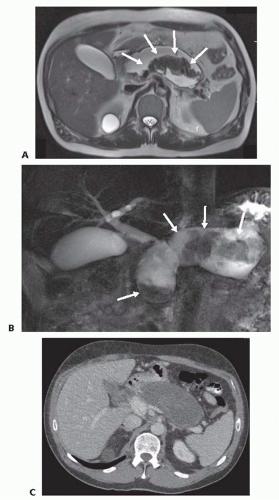

CT may not readily distinguish with high sensitivity solid from liquid content to distinguish pseudocyst from necrosis.1

WON may be better diagnosed based on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) to detect necrosis within the collection.1

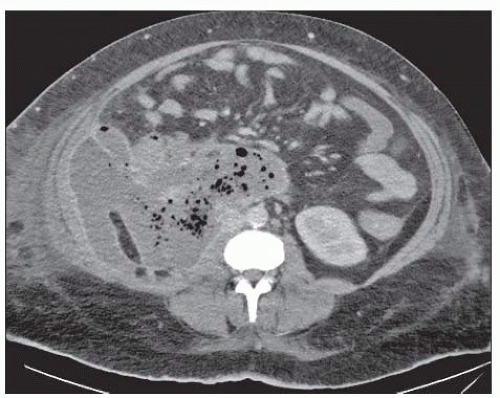

The diagnosis of infection (infected necrosis) of an acute necrotic collection (ANC) or of WON is based on the presence of gas within the collection on CT (FIG 3). This extraluminal gas is present in areas of necrosis. The diagnosis must be suspected in a patient with persistent organ failure, fevers, and elevated white blood count after the first week of admission. In situations where the diagnosis of infected necrosis is unclear, FNA for Gram stain and culture may be performed.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Positioning

The positioning of the patient needs to be selected based on the patient and the nature of the WON. In patients who are unstable, supine position is generally safer.

In patients with posteriorly located collections, the prone position may allow for better gravitational drainage of WON for better success.

TECHNIQUES

INITIAL ENDOSCOPY

Initial endoscopy is performed by using a therapeutic, side-viewing video duodenoscope, gastroscope, or echoendoscope.

We favor the use of general anesthesia to prevent aspiration.

Although we use air routinely, carbon dioxide (CO2) insufflation is always used during these procedures to minimize the theoretical risk of air embolism.

Antibiotics with good pancreatic penetration should be routinely given prior and after the procedure to patients who are not already on broad-spectrum antibiotics.

ENDOSCOPIC ULTRASOUND

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided access is strongly recommended when gastric varices are present or when no gastric or duodenal compression with bulge formation is present. EUS-guided drainage can avoid local complications related to blind endoscopic drainage.5

Under EUS guidance, the appropriate site of access to drain the WON can be established. This is particularly useful in patients without any bulging visible on endoscopy. The site in the gastric or duodenal lumen needs to be chosen and use of EUS is associated with fewer complications and higher success rates, particularly with those WON in the tail and those patients with varices to permit a safe passage of the needle.5

The most appropriate site of transmural puncture should be through a wall less than 10 mm in thickness. In those

who do not use EUS and in those patients in which no bulging on the gastric or duodenal wall is visible, the most recent cross-sectional imaging may help decide the site of puncture.6

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree