KEY CONCEPTS

![]() Endometriosis should be suspected in any woman of reproductive age with recurring cyclic or acyclic pelvic pain and/or subfertility, especially if pain does not improve with nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs and hormonal contraceptives.

Endometriosis should be suspected in any woman of reproductive age with recurring cyclic or acyclic pelvic pain and/or subfertility, especially if pain does not improve with nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs and hormonal contraceptives.

![]() The etiology of endometriosis is likely multifactorial and requires a genetic or immunologic predisposition. Retrograde menstruation is the most widely accepted theory to account for displacement of endometrial tissue, although alternative theories have been proposed.

The etiology of endometriosis is likely multifactorial and requires a genetic or immunologic predisposition. Retrograde menstruation is the most widely accepted theory to account for displacement of endometrial tissue, although alternative theories have been proposed.

![]() Treatment goals include improvement of painful symptoms and maintenance or improvement of fertility. Therapy is considered successful based on resolution of the patient’s symptoms or achievement of pregnancy.

Treatment goals include improvement of painful symptoms and maintenance or improvement of fertility. Therapy is considered successful based on resolution of the patient’s symptoms or achievement of pregnancy.

![]() Both drug therapy and surgery may treat endometriosis-related pain, but infertility can only be treated with surgery or assisted reproductive techniques.

Both drug therapy and surgery may treat endometriosis-related pain, but infertility can only be treated with surgery or assisted reproductive techniques.

![]() No medical therapy has been proven to be more effective than another; thus, the choice among agents is determined primarily by side effect profile, cost, and individual patient response.

No medical therapy has been proven to be more effective than another; thus, the choice among agents is determined primarily by side effect profile, cost, and individual patient response.

![]() For endometriosis pain, surgical therapy is typically reserved for medical therapy failure.

For endometriosis pain, surgical therapy is typically reserved for medical therapy failure.

![]() Diagnosis of endometriosis can be made only via surgical visualization of lesions, not by physical examination or laboratory testing. Empiric treatment without confirmation of diagnosis is acceptable in most cases.

Diagnosis of endometriosis can be made only via surgical visualization of lesions, not by physical examination or laboratory testing. Empiric treatment without confirmation of diagnosis is acceptable in most cases.

![]() To help avoid loss of bone mineral density, add-back therapy should be strongly considered in any woman receiving a gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist.

To help avoid loss of bone mineral density, add-back therapy should be strongly considered in any woman receiving a gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist.

INTRODUCTION

![]() Endometriosis causes secondary dysmenorrhea and is associated with infertility. Presence of endometrial tissue outside the uterus is chronic and relapsing. Endometriosis treatment targets pain relief and fertility improvement.

Endometriosis causes secondary dysmenorrhea and is associated with infertility. Presence of endometrial tissue outside the uterus is chronic and relapsing. Endometriosis treatment targets pain relief and fertility improvement.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

The prevalence of endometriosis is estimated at 5% to 10% of the general female population.1–4 Four percent of premenopausal women presenting to primary care for nongynecologic problems have endometriosis, and up to 80% of adult women and 50% of adolescents with chronic pelvic pain are diagnosed with the disorder.1,4–8 The incidence is 10-fold higher in women with infertility (20% to 50%) compared with that in fertile women (0.5% to 5%).1,4–7,9 A genetic predisposition for endometriosis has also been noted.2

ETIOLOGY

Endometriosis is characterized by findings of endometrial tissue outside of the normal uterine cavity. It may be diagnosed at any age, but is most commonly found during the reproductive years (range 12 to 80 years old, average 28 years).1,7 Risk of developing endometriosis increases with early menarche (≤11 years), shorter menstrual cycles (<27 days), and heavy, prolonged menstruation.4,7 Taller, thinner women are more likely to develop endometriosis than patients with higher body weights, body mass indexes, or waist-to-hip ratios potentially due to higher follicular-phase estradiol levels.7 Altered pelvic anatomy, such as Müllerian duct anomalies and cervical or vaginal outlet obstruction, also increases risk of developing endometriosis, as does in utero exposure to environmental toxins or potent estrogens.2,3,7 Conversely, higher parity, increased duration of lactation, regular exercise (>4 h/wk), greater birth weight, and breast-feeding decrease the risk of endometriosis.4,7

Gene mutation studies suggest genes regulating inflammation, sex steroid regulation, metabolism, biosynthesis, detoxification, vascular function, and tissue remodeling may contribute to endometriosis, but no validated associations have been confirmed.10 Alterations on chromosomes 7 and 10 have been identified in clusters of women with endometriosis.2 It is most likely that a multitude of genetic mutations are involved with the development of endometriosis.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

![]() Multiple theories exist to explain why endometrial tissue is present outside the uterine cavity, and the true pathophysiology is likely multifactorial.1–3,5 The most widely accepted theory proposes that endometrial tissue is deposited in the peritoneal cavity by retrograde menstruation through the fallopian tubes.3 However, retrograde menstruation occurs in up to 90% of women while only 10% to 15% develop endometriosis, indicating that additional factors are necessary for endometrial lesions to attach, survive, and proliferate.1,2,4 Alternative theories include the inappropriate differentiation of mesothelial cells into endometrium-like tissue (coelomic metaplasia), the differentiation of stem cells from either bone marrow or the endometrial basalis layer into endometrial-like tissues (stem cell theory), and the spread of menstrual tissue to distant sites through veins or lymphatic vessels (lymphatic or hematogenous spread).2,3

Multiple theories exist to explain why endometrial tissue is present outside the uterine cavity, and the true pathophysiology is likely multifactorial.1–3,5 The most widely accepted theory proposes that endometrial tissue is deposited in the peritoneal cavity by retrograde menstruation through the fallopian tubes.3 However, retrograde menstruation occurs in up to 90% of women while only 10% to 15% develop endometriosis, indicating that additional factors are necessary for endometrial lesions to attach, survive, and proliferate.1,2,4 Alternative theories include the inappropriate differentiation of mesothelial cells into endometrium-like tissue (coelomic metaplasia), the differentiation of stem cells from either bone marrow or the endometrial basalis layer into endometrial-like tissues (stem cell theory), and the spread of menstrual tissue to distant sites through veins or lymphatic vessels (lymphatic or hematogenous spread).2,3

Endometriosis is a chronic inflammatory disorder that exhibits cellular proliferation, cellular invasion, and angiogenesis not unlike solid tumor malignancies.11 Genetic alterations may predispose endometrial lesion survival in certain women, and immunologic abnormalities may decrease the clearance of displaced endometrial tissue.1,2,4 Findings of abnormal B- and T-cell function, decreased apoptosis, and altered levels of prostanoids, cytokines, growth factors, interleukins, and aromatase in endometrial lesions and peritoneal fluid of affected women support this theory.1,2,12

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Pain associated with endometriosis results from increased concentrations of inflammatory markers, including prostaglandins, and increased nerve density at lesion sites. Proinflammatory cytokines found in endometrial lesions, including tumor necrosis factor-α and interleukins 1, 6, and 8, promote lesion formation, adhesion, and infiltration and induce pain through pelvic nerve stimulation.2,4 Prostaglandin F2α induces vasoconstriction and can cause uterine contractions, a component of dysmenorrhea, while prostaglandin E2 can induce pain through direct actions on nerves.2 Increased density of sensory, cholinergic, and adrenergic nerves and an overexpression of nerve growth factors near lesions in endometrial tissue also cause pain.3 Researchers have demonstrated that these nerve fibers are found significantly more often in patients with endometriosis than in those without endometriosis, in greater density in patients with higher pain scores (≥3 vs. ≤20), and in greater density in patients with deep infiltrating lesions.11,13–15 The interplay between increased density of nerve fibers in endometrial lesions and increased concentrations of cytokines and prostaglandins in peritoneal fluid combines to confer significant pelvic pain in many patients.

The pathophysiology for infertility in endometriosis is less well defined, especially in mild disease. In advanced endometriosis, inflammation and anatomic abnormalities such as ovarian cysts and adhesions may physically block fallopian tubes and decrease receptivity of the endometrium, thus hindering oocyte and embryo development.2,4 The same inflammatory cytokines that lead to pain also create a hostile peritoneal environment leading to damage of sperm DNA and cell membranes.16 Hormonal dysregulation resulting from the disease also leads to decreased ovarian reserve, altered follicular morphology, oocyte dysfunction, and decreased efficacy of fertility treatments.17

TREATMENT

Endometriosis is a chronic, relapsing disease. Lifelong treatment plans must consider individual patient symptoms, goals for fertility, and impact on quality of life.18 Various organizations, including the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the American Society for Reproductive Medicine, the Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada, and the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology, have published recent evidence-based and/or expert opinion-based guidelines for treating endometriosis.4,6,18–20 These guidelines should be used to help inform treatment choice.

Desired Outcomes

Identification of endometriosis treatment goals depends on individual patient presentation and needs. ![]()

![]() Typical outcomes include minimization of associated pain, improved quality of life, and correction of associated infertility. The first two outcomes can often be achieved through use of pharmacologic therapy and surgery.4,6,18 Infertility is nonresponsive to medical therapies; thus, surgical intervention to remove endometrial lesions coupled with various assisted reproductive techniques must be employed.4,19 Even with such efforts, not all women with endometriosis will be able to conceive, and exact success rates are unknown due to a paucity of well-designed clinical studies.

Typical outcomes include minimization of associated pain, improved quality of life, and correction of associated infertility. The first two outcomes can often be achieved through use of pharmacologic therapy and surgery.4,6,18 Infertility is nonresponsive to medical therapies; thus, surgical intervention to remove endometrial lesions coupled with various assisted reproductive techniques must be employed.4,19 Even with such efforts, not all women with endometriosis will be able to conceive, and exact success rates are unknown due to a paucity of well-designed clinical studies.

General Approach to Treatment

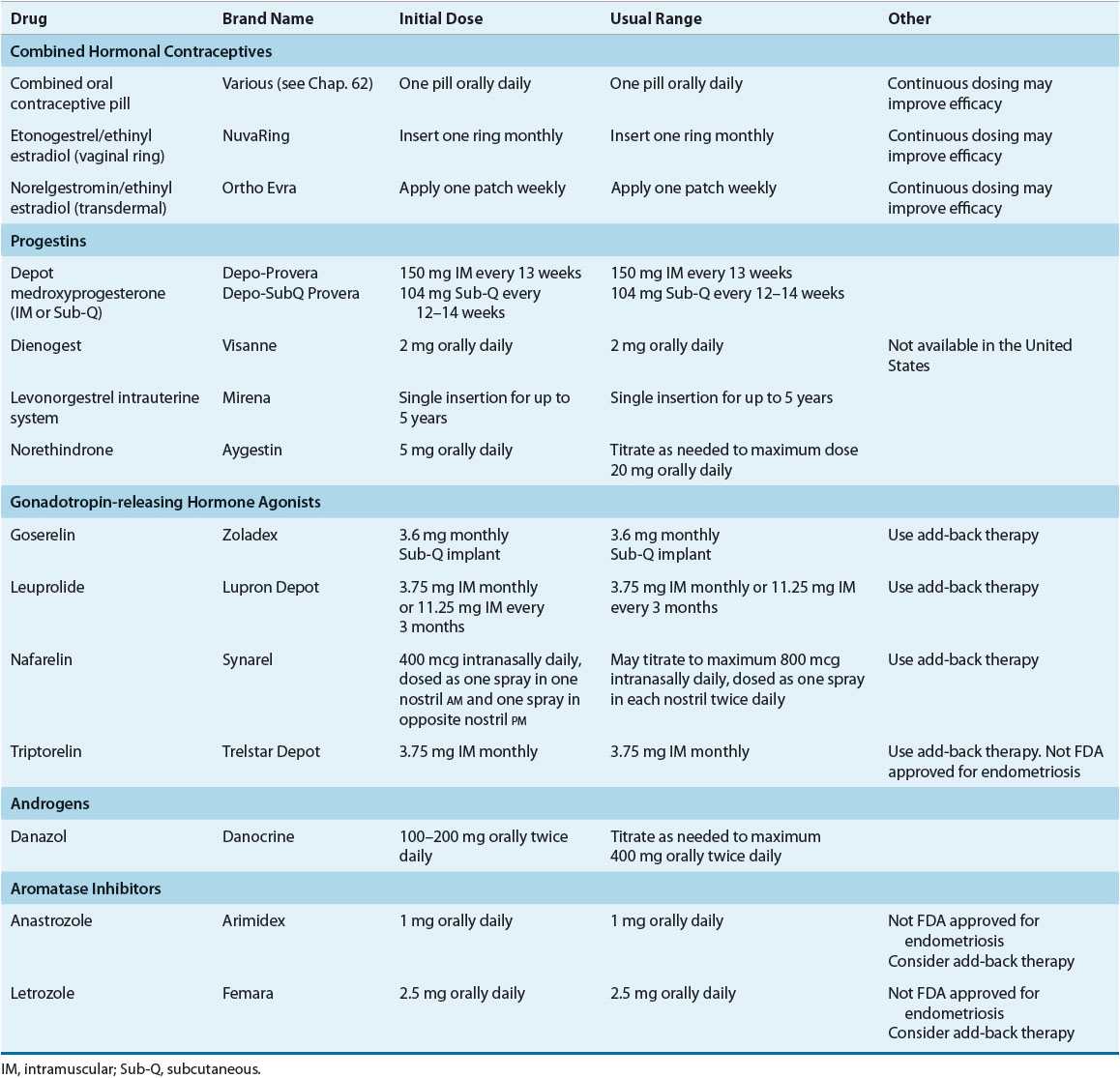

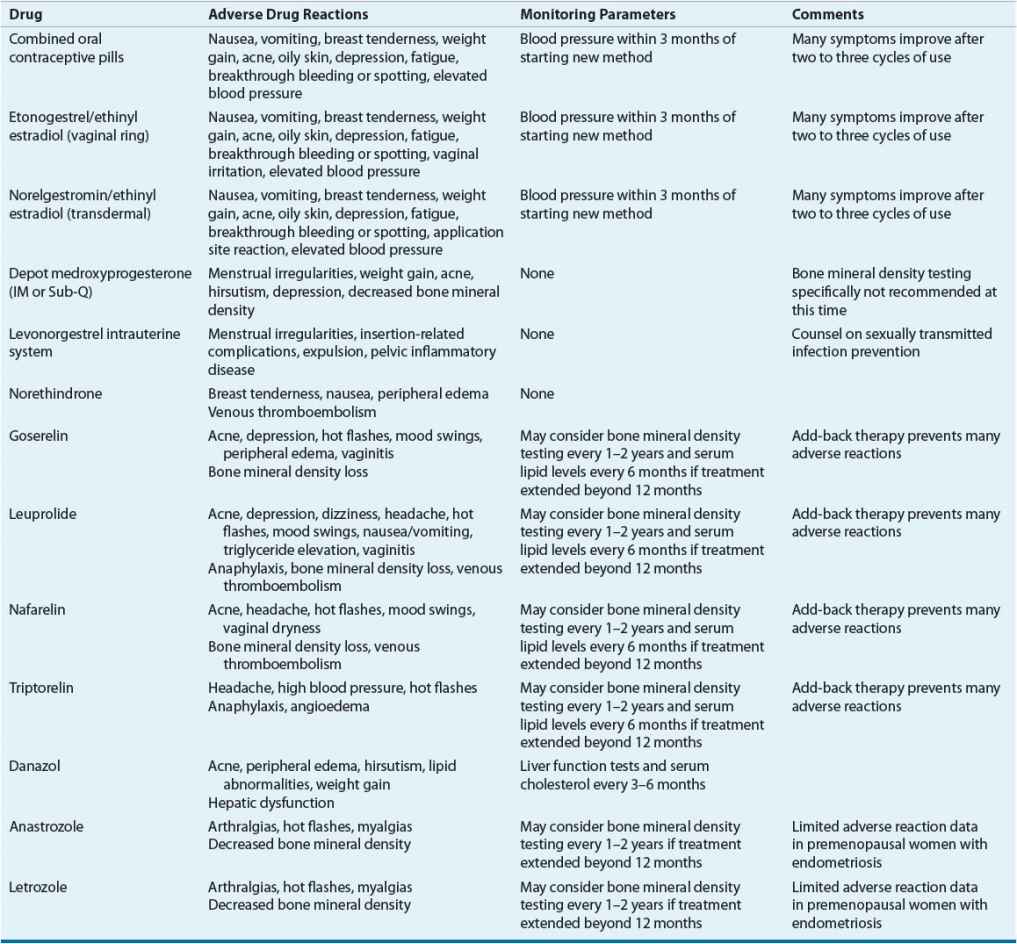

Treatment of the asymptomatic patient consists of expectant management (watchful waiting). For symptomatic patients, the foundation of therapy includes medical treatment, surgical treatment, or both. To date, no studies have directly compared medical and surgical treatment as first-line therapy. Furthermore, determining the optimal medical or surgical approach is difficult secondary to a paucity of well-designed, randomized controlled trials comparing options. ![]() All commonly prescribed medical therapies relieve endometriosis-related pain by regressing lesions via induction of a pseudopregnancy or pseudomenopausal state, but medications do not eradicate lesions or improve fertility. The choice of initial therapy depends on factors such as the patient’s primary complaint, the location and extent of disease, desire for future fertility, cost of therapy, contraindications to therapy, and potential side effects.4,6,18,20 Information regarding drugs commonly prescribed for endometriosis, their dosing, side effects, and special monitoring parameters are listed in Tables 64-1 and 64-2. No endometriosis treatments are guaranteed to provide full relief of symptoms; consequently, analgesics such as nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs or opioids are often used as adjunctive therapy for pain relief.

All commonly prescribed medical therapies relieve endometriosis-related pain by regressing lesions via induction of a pseudopregnancy or pseudomenopausal state, but medications do not eradicate lesions or improve fertility. The choice of initial therapy depends on factors such as the patient’s primary complaint, the location and extent of disease, desire for future fertility, cost of therapy, contraindications to therapy, and potential side effects.4,6,18,20 Information regarding drugs commonly prescribed for endometriosis, their dosing, side effects, and special monitoring parameters are listed in Tables 64-1 and 64-2. No endometriosis treatments are guaranteed to provide full relief of symptoms; consequently, analgesics such as nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs or opioids are often used as adjunctive therapy for pain relief.

TABLE 64-1 Dosing of Drugs Used in Treatment of Endometriosis

TABLE 64-2 Monitoring Drug Therapy for Endometriosis

Nonpharmacologic Therapy

Surgery, generally performed via laparoscopy, is used in endometriosis as both a diagnostic and a therapeutic tool.19,20 ![]()

![]() Due to lack of data supporting superiority of surgery over medical therapies in relieving endometriosis pain, surgical therapy is typically reserved for patients experiencing medication failure or who suffer from infertility. Women with continuing pain symptoms who do not desire pregnancy may be offered the option of hysterectomy with or without oophorectomy. In one long-term followup study conducted at the Cleveland Clinic, surgery-free rates 7 years after initial surgery were lower with laparotomy alone versus hysterectomy (45.7% vs. 84.6% surgery free).21 In both groups, ovary removal did not improve surgery-free rates regardless of baseline ovarian disease involvement.21

Due to lack of data supporting superiority of surgery over medical therapies in relieving endometriosis pain, surgical therapy is typically reserved for patients experiencing medication failure or who suffer from infertility. Women with continuing pain symptoms who do not desire pregnancy may be offered the option of hysterectomy with or without oophorectomy. In one long-term followup study conducted at the Cleveland Clinic, surgery-free rates 7 years after initial surgery were lower with laparotomy alone versus hysterectomy (45.7% vs. 84.6% surgery free).21 In both groups, ovary removal did not improve surgery-free rates regardless of baseline ovarian disease involvement.21

Clinical Controversy…

< div class='tao-gold-member'>