Chapter 16 Endocrine System

Endocrine Diseases

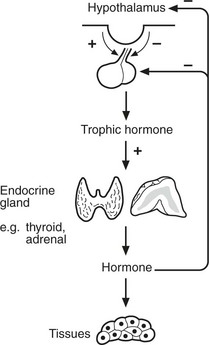

Most endocrine glands are controlled by hormones produced in the anterior pituitary, themselves under control of substances produced in the hypothalamus. A variety of stimuli control pituitary and hypothalamic hormone release, especially feedback control from hormone levels from the target glands. Levels of pituitary hormones show a circadian rhythm.

Endocrine diseases can be broadly classified as:

Effects of non-functioning tumours

Pituitary Gland

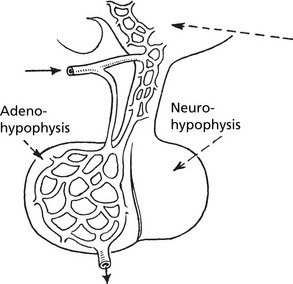

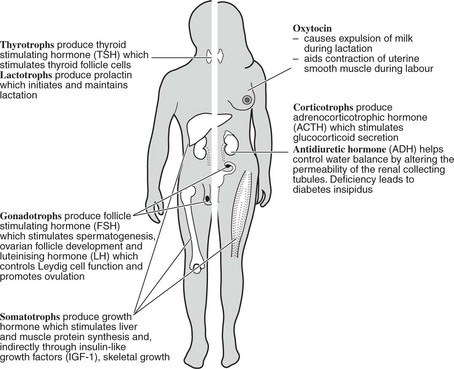

The pituitary has two parts; the anterior (adenohypophysis) and the posterior (neurohypophysis).

Pituitary Hyperfunction

In most cases, this is associated with pituitary adenoma.

Small tumours present only if they produce excess hormones, while larger tumours may cause pressure effects (e.g. on optic chiasma, page 141) or with hypopituitarism due to destruction of normal pituitary. Occasionally haemorrhage into a pituitary adenoma causes raised intracranial pressure (pituitary apoplexy).

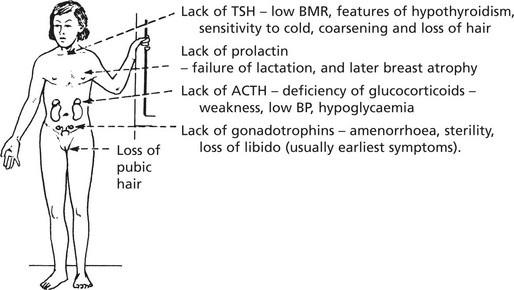

Hypopituitarism

Failure of pituitary secretion may affect one or several hormones. Causes include:

In time, the peripheral endocrine organs – thyroid, adrenals, ovaries – show atrophy.

Note: Some individuals treated with human growth hormone have developed Creutzfeld–Jacob disease (p.555).

In adults, GH deficiency leads to lethargy, diminished muscle mass, obesity and premature atheroma.

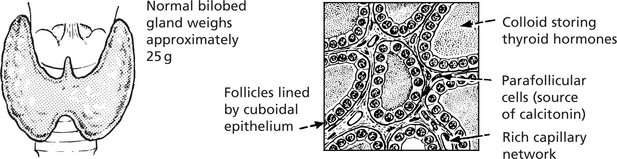

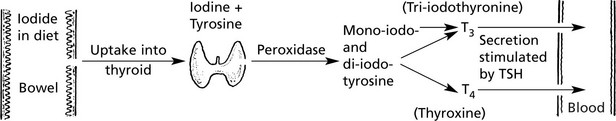

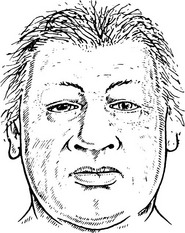

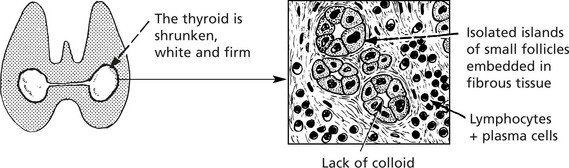

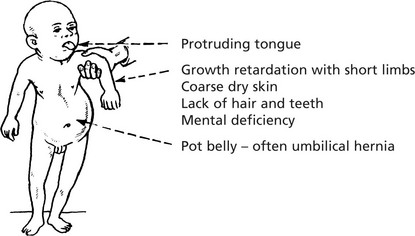

Thyroid Gland – Underactivity

The thyroid gland is under the control of the pituitary thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH p.623).

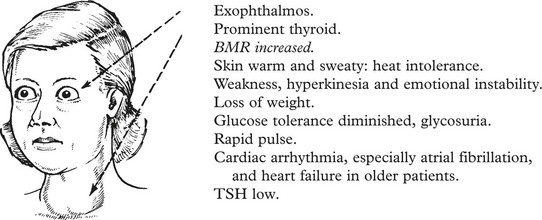

Thyroid Gland – Overactivity

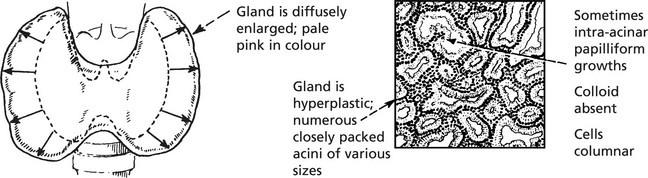

Endemic Cretinism

This occurs in districts where goitre is common due to iodine deficiency. The infantile thyroid is usually enlarged and nodular. Histologically, there are hyperplastic foci containing colloid which compress the intervening tissue. The incidence of this disorder has reduced following addition of iodine to salt.