20 Endocrine surgery

Thyroid gland

Surgical anatomy and development

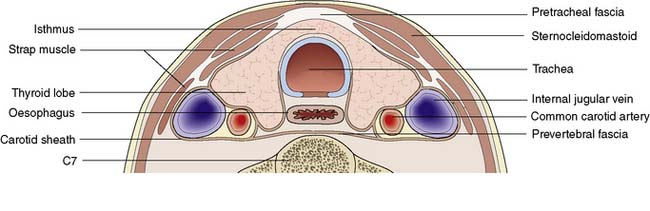

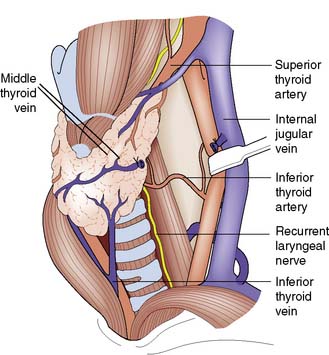

The lobes of the thyroid lie on the front and sides of the trachea and larynx at the level of the 5–7th cervical vertebrae (Fig. 20.1). They are connected by a narrow isthmus, which overlies the second and third tracheal rings. The thyroid normally weighs 15–30 g and is invested by the pre-tracheal fascia, which binds it to the larynx, cricoid cartilage and trachea (Fig. 20.2). The strap muscles (sternohyoid and sternothyroid) lie in front of the pretracheal fascia and must be separated to gain access to the gland. It is difficult to feel the normal thyroid gland except at puberty and during pregnancy, when physiological enlargement occurs.

Fig. 20.1 Anatomy of the thyroid gland.

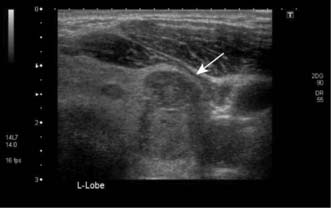

The middle thyroid vein has been divided to allow forward rotation of the left lobe of the gland.

Assessment of thyroid disease

The thyroid can be imaged by ultrasonography (Fig. 20.3) or radioisotope scanning (99mTc-sodium pertechnetate behaves like iodine and is ‘trapped’ by the gland). The main value of scanning is to differentiate between ‘hot’ (actively functioning), ‘cool’ (normally functioning) and ‘cold’ (non-functioning) thyroid nodules. Total isotope uptake also reflects thyroid activity.

Enlargement of the thyroid gland (goitre)

Clinical features

Goitre is a visible or palpable enlargement of the thyroid (Fig. 20.4). The swelling appears in the lower part of the neck and retains the shape of the normal gland (thyreos – Greek for shield). The swelling characteristically moves upwards on swallowing because of the gland’s attachment to the trachea. Patients may have a dry mouth, and when asking them to swallow, water should be provided.

Non-toxic nodular goitre

Investigations

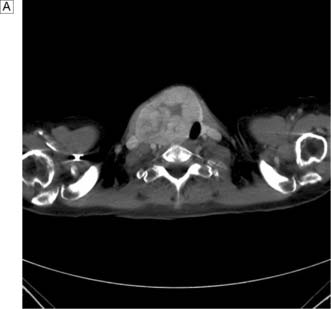

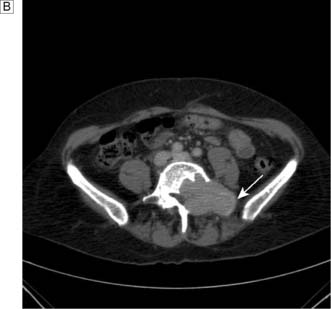

In the case of retrosternal goitre, plain films of the thoracic inlet may reveal tracheal deviation (Fig. 20.5A) and CT may show tracheal compression (Fig. 20.5B) The presence of stridor indicates compromise of the tracheal lumen. T3, T4 and TSH are usually normal and that being the case isotope scans are not indicated.

Thyrotoxic goitre

Summary Box 20.1 Goitres

• Physiological thyroid enlargement may occur during puberty or pregnancy

• Non-toxic nodular goitre can be associated with iodine deficiency and drug reactions; it is usually asymptomatic but can cause compression symptoms

• Thyrotoxic goitre results from stimulation of the gland by TSH or TSH-like proteins, resulting in excessive production of T3 and T4. About 25% of cases of thyrotoxicosis are due to a toxic multinodular goitre (a long-standing non-toxic goitre develops hyperactive nodule(s) that function independently of TSH levels)

• Thyroiditis can produce diffuse painful swelling that may be subacute (de Quervain’s disease) or autoimmune (Hashimoto’s disease). Riedel’s thyroiditis is a very rare cause of painless thyroid swelling and tracheal compression

• A solitary thyroid nodule is often a conspicuous palpable nodule in a multinodular goitre. True solitary nodules may be adenomas, cysts or cancers, conditions that are distinguished by fine-needle aspiration cytology, ultrasonography, isotope scans and function tests

• Thyroid cancers can produce a goitre, particularly in the case of medullary carcinoma of the thyroid and lymphoma.

Thyroiditis

Solitary thyroid nodules

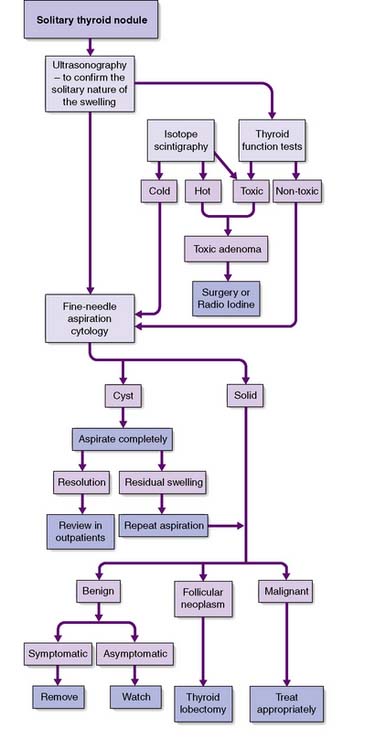

Slow-growing and painless clinically ‘solitary’ nodules are common, although 50% of them are really part of a multinodular goitre. Of the true solitary nodules, half are benign adenomas and the rest are cysts or differentiated cancers. The pivotal diagnostic test is fine-needle aspiration cytology, complemented by ultrasonography, isotope scans and thyroid function tests (Fig. 20.6). Cysts can be aspirated and, provided that they do not refill and that the cytology is negative for neoplastic cells, they need not be removed. Very rarely, a cyst contains a carcinoma (often papillary) within its wall, and blood-stained aspirate or a residual swelling after aspiration should raise this possibility. A cytopathologist cannot distinguish between a follicular adenoma and follicular carcinoma; this can only be achieved on definitive histopathology by looking for capsular or vascular invasion. Diagnostic surgery is needed if aspiration reveals a follicular neoplasm. Intraoperative frozen section does not always provide a definitive diagnosis, but the demonstration of carcinoma by whatever means indicates that more extensive surgery may be needed (e.g. complete total thyroidectomy).

Hyperthyroidism

Primary thyrotoxicosis (Graves’ disease)

Clinical features

Malignant tumours of the thyroid

Thyroid cancer accounts for less than 1% of all forms of malignancy. As with all thyroid disease, females are more often affected (male:female ratio 1:3). The two main types of thyroid carcinoma are papillary (50%) and follicular (30%), with the remainder comprising medullary carcinoma, anaplastic carcinoma and lymphoma (EBM 20.1). The incidence of thyroid cancer is increased by exposure to ionizing radiation: for example, following the Chernobyl disaster.

20.1 Relevant websites and publications for the management of thyroid cancer are:

• www.aace.com/pub/guidelines/index.php American Association of Endocrine Surgeons, thyroid_carcinoma guidelines.

• www.baets.org.uk/Pages/guidelines/.php British Association of Endocrine and Thyroid Surgeons.

• www.british-thyroid-association.org National thyroid cancer guidelines group of the British Thyroid Association.

• Northern Cancer Network. Guidelines for management of thyroid cancer. Clinical Oncology 2000; 12:373–391.

Follicular carcinoma

Clinical features

This disease typically presents as a solitary thyroid nodule in patients aged 30–50 years. Lymph node metastases are much less common than haematogenous spread, with deposits in the lungs, bone or liver (Fig. 20.8). Histologically, malignant cells are arranged in solid masses with rudimentary acini. Vascular and capsular invasion characterize this neoplasm and distinguish it from a benign follicular adenoma.

Thyroidectomy

Technique

Summary Box 20.2 Thyroid cancer

• Thyroid cancers may arise from the epithelium (papillary 50%, follicular 30%). Remainder comprise anaplastic, parafollicular C cells (medullary carcinoma) or lymphoreticular tissue (lymphoma)

• Papillary cancers are rare after the age of 40 years, are often multifocal and spread to lymph nodes, but rarely disseminate widely. Total or near-total thyroidectomy with the removal of involved nodes may be followed by radioiodine, and thyroid replacement therapy to suppress TSH. Ten-year survival rates approach 90%

• Follicular carcinoma occurs in the 30–50-year age group, spreads preferentially via the bloodstream, and is treated by total thyroidectomy. Residual neck or skeletal radioisotope uptake signals the need for radioiodine therapy. T4 is used routinely to suppress TSH production. The 10-year survival rate is 75%

• Anaplastic carcinoma occurs in older patients, spreads locally and frequently gives rise to pulmonary metastases. Curative resection is rarely possible, radiotherapy/chemotherapy is of little value, and most patients die within 1 year

• Medullary carcinomas secrete calcitonin, may involve both lobes, and involve neck nodes. They may be sporadic or part of MEN II. Treatment consists of total thyroidectomy and node dissection.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree