10 Endocrine disease

Endocrinology concerns the synthesis, secretion and action of hormones. These are chemical messengers released from endocrine glands that coordinate the activities of many different cells. Endocrine disease, therefore, has a wide range of manifestations in many organs.

MAJOR ENDOCRINE FUNCTIONS AND ANATOMY

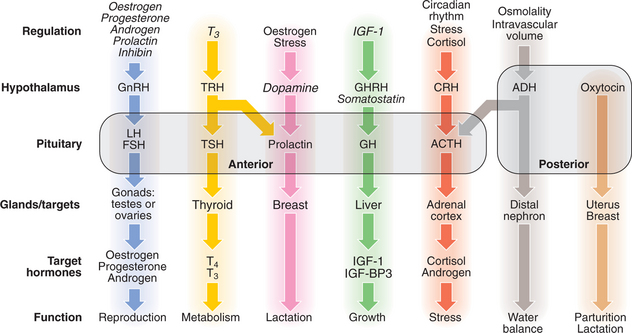

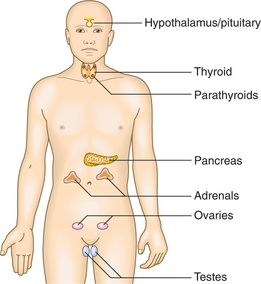

Although some endocrine glands (e.g. the parathyroids and pancreas) respond directly to metabolic signals, most are controlled by hormones released from the pituitary gland. Anterior pituitary hormone secretion is controlled in turn by substances produced in the hypothalamus and released into portal blood which flows down the pituitary stalk. Posterior pituitary hormones are synthesised in the hypothalamus and transported down nerve axons to be released from the posterior pituitary. Hormone release in the hypothalamus and pituitary is regulated by numerous nervous, metabolic, physical or hormonal stimuli, in particular feedback control by hormones produced by target glands (thyroid, adrenal cortex and gonads). These integrated endocrine systems are called ‘axes’ (Figs 10.1, 10.2).

The classical model of endocrine function involves hormones which are synthesised in endocrine glands and are released into the circulation, acting at sites distant from those of secretion. However, most major organs also secrete hormones or contribute to the metabolism and activation of prohormones; many hormones act on adjacent cells (paracrine system, e.g. neurotransmitters) or even back on the cell of origin (autocrine system); and the sensitivity of target tissues is regulated in a tissue-specific fashion. Some hormones (e.g. insulin, adrenaline (epinephrine)) act on specific cell surface receptors. Other hormones (e.g. steroids, triiodothyronine, vitamin D) bind to specific intracellular receptors, which in turn bind to response elements on DNA to regulate gene transcription.

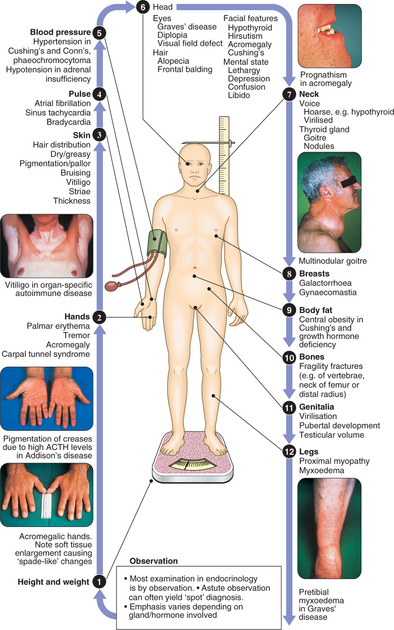

CLINICAL EXAMINATION IN ENDOCRINE DISEASE

Pathology arising within an endocrine gland is often called ‘primary’ disease (e.g. primary hypothyroidism in Hashimoto’s thyroiditis), while abnormal stimulation of the gland is often called ‘secondary’ disease (e.g. secondary hypothyroidism in patients with thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) deficiency).

PRESENTING PROBLEMS IN ENDOCRINE DISEASE

Patients with endocrine disease present in many ways, to many different specialists, reflecting the diverse effects of hormone deficiency and excess. Presenting symptoms are often non-specific and long-standing (Box 10.1). In many patients, endocrine disease is asymptomatic and detected by routine biochemical testing. The most common classical presentations are of thyroid disease, reproductive disorders and hypercalcaemia. In addition, endocrine diseases are often part of the differential diagnosis of other disorders, including electrolyte abnormalities, hypertension, obesity and osteoporosis. Although diseases of the adrenal glands, hypothalamus and pituitary are relatively rare, their diagnosis often relies on astute clinical observation in a patient with non-specific complaints, so it is important that clinicians are familiar with their key features.

10.1 MOST COMMON PRESENTING SYMPTOMS OF ENDOCRINE DISEASE ![]()

| Symptom | Most likely disorder(s) |

|---|---|

| Lethargy/depression | Hypothyroidism, DM, Cushing’s syndrome, hyperparathyroidism, hypogonadism, adrenal insufficiency |

| Weight gain | Hypothyroidism, Cushing’s |

| Weight loss | Thyrotoxicosis, adrenal insufficiency, DM |

| Proptosis | Graves’ disease |

| Thyroid nodule | Solitary thyroid nodule, dominant nodule in multinodular goitre |

| Polyuria/polydipsia | DM, diabetes insipidus, hyperparathyroidism, Conn’s syndrome |

| Coarse features | Acromegaly, hypothyroidism |

| Galactorrhoea | Hyperprolactinaemia |

| Ureteric colic | Hyperparathyroidism |

| Paraesthesiae/tetany | Hypoparathyroidism |

| Muscle weakness (usually proximal) | Thyrotoxicosis, Cushing’s, hypokalaemia (e.g. Conn’s), hyperparathyroidism, hypogonadism |

| Heat intolerance | Thyrotoxicosis, menopause |

| Thyroid swelling | Simple goitre, Graves’ disease, Hashimoto’s thyroiditis |

| Palpitations | Thyrotoxicosis, phaeochromocytoma |

| Hirsutism | Idiopathic, PCOS, congenital adrenal hyperplasia, Cushing’s |

| Amenorrhoea/oligomenorrhoea | Menopause, PCOS, hyperprolactinaemia, thyrotoxicosis, premature ovarian failure, Cushing’s |

| Pain over thyroid | Haemorrhage into nodule, de Quervain’s thyroiditis |

| Loss of libido | Male hypogonadism |

| Headache | Acromegaly, pituitary tumour, phaeochromocytoma |

| Visual dysfunction | Pituitary tumour |

(DM = diabetes mellitus; PCOS = polycystic ovarian syndrome)

THE THYROID GLAND

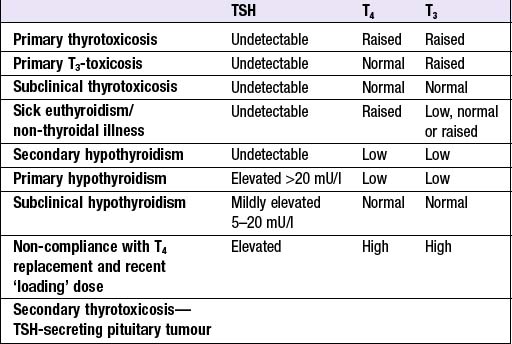

Production of T3 and T4 in the thyroid is stimulated by thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), a glycoprotein released from the thyrotroph cells of the anterior pituitary in response to the hypothalamic tripeptide, thyrotrophin-releasing hormone (TRH). There is a negative feedback of thyroid hormones on the hypothalamus and pituitary such that in thyrotoxicosis, when plasma concentrations of T3 and T4 are raised, TSH secretion is suppressed. Conversely, in primary hypothyroidism low T3 and T4 are associated with high circulating TSH levels. TSH is, therefore, regarded as the most useful investigation of thyroid function. However, TSH may take several weeks to ‘catch up’ with T4/T3 levels, e.g. after prolonged suppression of TSH in thyrotoxicosis is relieved by antithyroid therapy. Common patterns of abnormal thyroid function tests (TFTs) are shown in Box 10.2.

PRESENTING PROBLEMS

THYROTOXICOSIS

Clinical assessment

Manifestations of thyrotoxicosis are shown in Box 10.3. The most common symptoms are:

10.3 CLINICAL FEATURES OF THYROTOXICOSIS ![]()

| Symptoms | Signs | |

|---|---|---|

| General | Weight loss (normal appetite), heat intolerance, fatigue, apathy1, osteoporosis | Weight loss, goitre with bruit2, lymphadenopathy3 |

| GI | Hyperdefecation, diarrhoea, steatorrhoea, anorexia1, vomiting3 | |

| Cardio-respiratory | Palpitations, dyspnoea on exertion, angina, ankle swelling, asthma exacerbation3 | Sinus tachycardia, atrial fibrillation, systolic hypertension, cardiac failure |

| Neuromuscular | Anxiety, irritability, emotional lability, psychosis, tremor, weakness | Tremor, hyper-reflexia, ill-sustained clonus, proximal/bulbar1 myopathy |

| Dermatological | Sweating, pruritus, alopecia | Palmar erythema, pretibial myxoedema2, thyroid acropachy2, onycholysis3, pigmentation3, vitiligo2 |

| Reproductive | Oligo-/amenorrhoea, infertility, ↓libido, impotence | Gynaecomastia |

| Ocular | Grittiness, red eyes, excessive lacrimation, diplopia2, loss of acuity2 | Lid retraction, lid lag, chemosis2, exophthalmos2, periorbital oedema2, corneal ulceration2, ophthalmoplegia2, papilloedema2 |

Italics indicate common features.

1 Particularly in elderly patients.

All causes of thyrotoxicosis can cause lid retraction and lid lag, but only Graves’ disease causes other ocular features (see Box 10.3).

Investigations

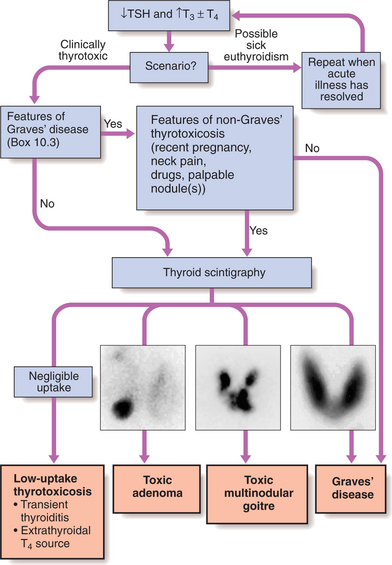

Figure 10.3 summarises the approach to establishing the diagnosis.

Imaging: 99mTechnetium scintigraphy scans indicate trapping of isotope in the gland (see Fig. 10.3). Iodine can also be used but yields lower resolution images.

Management

Definitive treatment of thyrotoxicosis depends on the underlying cause (see pp. 343–346) and may include antithyroid drugs, radioactive iodine or surgery. A non-selective β-blocker (propranolol 160 mg daily) will alleviate symptoms within 24–48 hrs.

Atrial fibrillation (AF) in thyrotoxicosis: AF is present in ∼10% of all patients with thyrotoxicosis (more in the elderly). Subclinical thyrotoxicosis is also a risk factor for AF. Ventricular rate responds better to β-blockade than digoxin. Thromboembolic complications are particularly common so anticoagulation with warfarin is indicated. Once the patient is biochemically euthyroid, AF reverts to sinus rhythm spontaneously in ∼50% of patients.

Patients should be rehydrated and given broad-spectrum antibiotics.

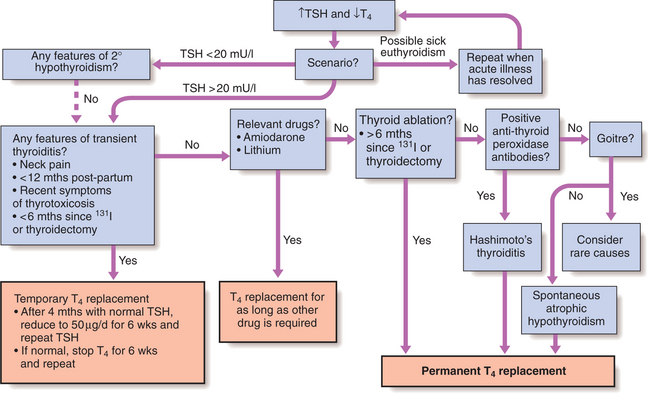

HYPOTHYROIDISM

The prevalence of primary hypothyroidism is 1 in 100, with a female : male ratio of 6 : 1.

Clinical assessment

Clinical features depend on the duration and severity of the hypothyroidism. The classical clinical features listed in Box 10.4 occur when deficiency develops insidiously over months/years.

10.4 CLINICAL FEATURES OF HYPOTHYROIDISM ![]()

| Symptoms | Signs | |

|---|---|---|

| General | Weight gain, cold intolerance, fatigue, somnolence, hoarseness | Weight gain, hoarseness, goitre, macrocytosis, anaemia |

| GI | Constipation | Ileus*, ascites* |

| Cardio-respiratory | Bradycardia, hypertension, pericardial/pleural effusions* | |

| Neuromuscular | Carpal tunnel syndrome, muscle stiffness, deafness, depression, psychosis* | Delayed relaxation of reflexes, cerebellar ataxia*, myotonia* |

| Dermatological | Dry skin, dry hair, alopecia | Myxoedema, purplish lips, malar flush, vitiligo, erythema ab igne |

| Reproductive | Menorrhagia, infertility, galactorrhoea*, impotence* | |

| Ocular | Periorbital oedema, loss of lateral eyebrows |

Italics indicate common features.

Investigations

Management

Most patients require life-long thyroxine therapy. A replacement regimen is:

Myxoedema coma is a medical emergency and treatment must begin before biochemical confirmation of the diagnosis. Triiodothyronine is given as an i.v. bolus of 20 μg followed by 20 μg 8-hourly until there is sustained clinical improvement. After 48–72 hrs, oral thyroxine (50 μg daily) may be substituted. Unless the patient has primary hypothyroidism, the thyroid failure should be assumed to be secondary to hypothalamic or pituitary disease and treatment given with hydrocortisone 100 mg 8-hourly, pending TFT and cortisol results. Other measures include slow rewarming, cautious i.v. fluids, broad-spectrum antibiotics and high-flow oxygen with or without assisted ventilation.

THYROID ENLARGEMENT

Palpable thyroid enlargement affects 5% of the population but a minority seek medical attention. Multinodular goitres and solitary nodules sometimes present with acute painful enlargement due to haemorrhage into a nodule. There are several causes of thyroid enlargement (Box 10.5). Whereas diffuse and multinodular goitre are invariably benign, there is a 1 : 20 chance of malignancy in a solitary lesion. TFTs should always be performed.

Solitary thyroid nodule: It is important to determine whether the nodule is benign or malignant. Cervical lymphadenopathy increases the likelihood of malignancy, as does a solitary nodule presenting in the elderly. Rarely, a metastasis from renal, breast or lung carcinoma presents as a painful, rapidly growing solitary nodule.

AUTOIMMUNE THYROID DISEASE

GRAVES’ DISEASE

The most common manifestation is thyrotoxicosis with or without a diffuse goitre. Clinical features are described in Box 10.3. Graves’ disease also causes ophthalmopathy and rarely pretibial myxoedema. These features can occur in the absence of thyroid dysfunction. Graves’ disease most commonly affects women aged 30–50 yrs.

Graves’ thyrotoxicosis

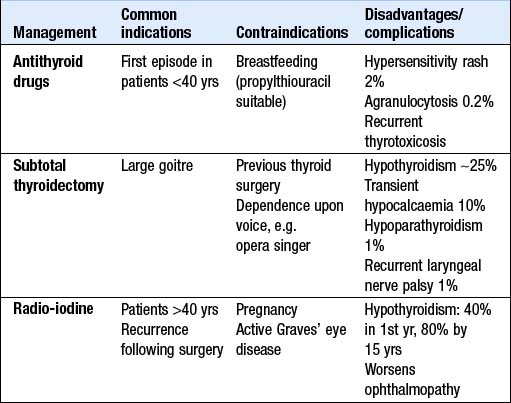

Management

Symptoms respond to β-blockade but definitive treatment requires control of thyroid hormone secretion. The different options are compared in Box 10.6. For patients <40 yrs old many centres prescribe a course of carbimazole and recommend surgery if relapse occurs, while 131I is employed as first- or second-line treatment in older patients. It is unclear whether 131I increases the incidence of some malignancies; the association may be with Graves’ disease rather than its therapy. In many centres, however, 131I is used more extensively, even in young patients.

Subtotal thyroidectomy: Patients must be rendered euthyroid before operation. Potassium iodide, 60 mg 8-hourly orally, is given for 2 wks before surgery to inhibit thyroid hormone release and reduce the size and vascularity of the gland, making surgery technically easier. Complications are uncommon (see Box 10.6). One year post-surgery, 80% of patients are euthyroid, 15% are hypothyroid and 5% remain thyrotoxic. Hypothyroidism within 6 mths of operation may be temporary. Long-term follow-up is necessary, as the late development of hypothyroidism and recurrence of thyrotoxicosis are well recognised.

Thyrotoxicosis in pregnancy

Treatment with propylthiouracil is preferred, as carbimazole is rarely associated with the childhood skin defect, aplasia cutis. The smallest dose of propylthiouracil (<150 mg/day) is used that maintains maternal TFTs within their normal ranges, thereby minimising fetal hypothyroidism and goitre. TRAb levels in the third trimester predict the likelihood of neonatal thyrotoxicosis; if they are not elevated, antithyroid drugs can be discontinued 4 wks before delivery to avoid fetal hypothyroidism at the time of maximum brain development. • During breastfeeding, propylthiouracil is used, as it is minimally excreted in the milk.

TRANSIENT THYROIDITIS

SUBACUTE (DE QUERVAIN’S) THYROIDITIS

IODINE-ASSOCIATED THYROID DISEASE

SIMPLE AND MULTINODULAR GOITRE

MULTINODULAR GOITRE

Clinical features and investigations

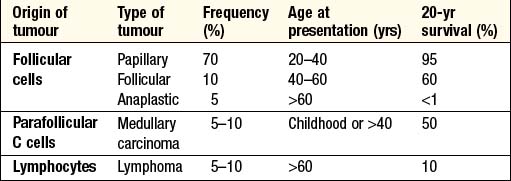

THYROID NEOPLASIA

Patients with thyroid tumours usually present with a solitary nodule (p. 341). Most are benign and a few (toxic adenomas) secrete excess thyroid hormones. Primary thyroid malignancy is rare (<1% of all carcinomas). As shown in Box 10.7, it can be classified according to the cell type of origin. With the exception of medullary carcinoma, thyroid cancer is more common in females.