End and Diverting Loop Ileostomies: Creation and Reversal

Kathrin Mayer Troppmann

END AND DIVERTING LOOP ILEOSTOMIES: CREATION

DEFINITION

An ileostomy is an artificially created opening of the distal ileum that is externalized on the abdominal wall. It can be temporary or permanent.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

A thorough review of the patient’s history and a physical examination, including a review of all past operative notes and diagnostic studies, are necessary to carefully select patients who are appropriate candidates for an ileostomy and to determine the most appropriate type of ileostomy to be created.

The history and the physical examination should be obtained with the functional and anatomic implications, treatment plan, and prognosis of the underlying disease in mind.

Additionally, the patient’s comorbidities, ability to perform activities of daily living and self-care, mobility limitations, and body contour must be thoroughly assessed.

PREOPERATIVE IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Appropriate imaging studies must be obtained according to the patient’s underlying disease and diagnosis. Any abnormal findings should be thoroughly worked up to ensure that the correct operation and diversion techniques are chosen. These tests may include the following:

Colonoscopy with biopsy if malignancy or inflammatory bowel disease is suspected

Computed tomography (CT) scan, upper gastrointestinal contrast study, and fistulogram to rule out intestinal obstruction or leak and to assess underlying disease severity

Anal manometry and endorectal ultrasound to evaluate the anal sphincter

Colonic motility study (e.g., SITZMARKS® test) to identify the region of intestinal dysmotility and to tailor the procedure and type of stoma to the patient’s needs

Prior to ileostomy formation, the nutritional status must be assessed (including albumin and prealbumin levels) and the patient’s comorbidities must be addressed (e.g., coronary artery disease, diabetes [HbA1c]) in order to minimize perioperative risk.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

General Considerations

If possible, a stoma should be avoided, as the morbidity of creation and reversal can be significant.

An ileostomy can be constructed as an end ileostomy (Brooke ileostomy) or as a diverting loop ileostomy. Alternatives to the more commonly used end and loop ileostomy techniques include the divided (or separated) loop ileostomy for maximizing fecal diversion and the end-loop (or loop-end) ileostomy for patients with a short, contracted mesentery and vascular pedicle.

An end ileostomy is the preferred configuration for a permanent ileostomy because it allows for a symmetric and protruding spout that is more easily constructed and managed.

Permanent end ileostomies are usually created when the distal intestine is not suitable for restoration of intestinal continuity due to underlying disease or poor intestinal function. Typical scenarios include:

Following total proctocolectomy for inflammatory bowel disease or familial adenomatous polyposis

Following subtotal colectomy for slow-transit constipation with concomitant severe pelvic floor dyssynergia

Fecal incontinence

Congenital anomalies

Temporary end ileostomies are typically created under the following circumstances:

Following subtotal colectomy for acute diverticular bleeding or ulcerative colitis-related toxic megacolon

Temporary or permanent diverting loop ileostomies are created when diversion of the fecal stream and decompression of the distal bowel are necessary:

Following distal ileal or colonic anastomoses at high risk for disruption due to:

Malnutrition or immunocompromised status

Anastomotic location within an irradiated, inflamed, or contaminated field

Low pelvic anastomotic location following sphincterpreserving procedures (e.g., ileal pouch-anal anastomoses, coloanal or low colorectal anastomoses)

Disruption of a previously created distal anastomosis

Distal bowel perforation

Pelvic sepsis

Rectal trauma

Complicated diverticulitis

Following anal sphincter reconstruction

Following rectovaginal fistula repair

Fecal incontinence

Severe radiation proctitis

Obstructing or nearly obstructing colorectal cancer, carcinomatosis, and Crohn’s disease

Sacral decubitus ulcer

Necrotizing perineal and gluteal soft tissue infections.

Preoperative Planning

The ideal stoma has no necrosis, prolapse, or retraction. Daily output ranges from 500 to 1000 mL, the appliance does not leak, and the skin is healthy. The importance of appropriate planning to ensure an optimal ileostomy location

and to maximize the opportunity for creation of a viable, tension-free, and well-functioning ileostomy cannot be overemphasized. Attention to these principles will decrease the time required for stoma management and minimize patient frustration.

A comprehensive discussion with the patient about the proposed ileostomy procedure, alternatives, and postoperative lifestyle is imperative.

Most stoma patients are elderly and many have their stoma care performed by a spouse, offspring, or caretaker; it is thus critical to involve these providers in the stoma education process.

Ideally, patients must be mentally and physically ready for a stoma and must therefore be informed as early as possible in their course of the disease regarding the potential need for a stoma. For many patients, though, an ileostomy is created in an acute setting at the end of a long, often life-saving procedure.

Stoma Education

A comprehensive perioperative educational program decreases readmissions and complications related to dehydration and appliance problems and optimizes postoperative patient satisfaction and participation in activities of daily life.

Wound ostomy continence nurse (WOCN) or enterostomal therapy (ET) nurse

Optimal stoma management begins with preoperative patient education in regard to diet, activities, clothing, and sexuality. The nurse can provide emotional and physical support. The patient must be informed that self-care may be awkward initially but that it can be learned and mastered.

Patient support groups, United Ostomy Association visitor

Patients should be introduced to other individuals with ileostomies who have similar socioeconomic and disease backgrounds. These encounters and relationships can help to improve morale and can reassure patients that they can have a satisfactory quality of life. Meetings should occur pre- and postoperatively (particularly during the first 3 to 6 months).

Stoma preparedness literature

The American College of Surgeons has created a comprehensive stoma preparedness kit including an educational DVD and manual, a stoma model, and stoma appliance samples.

Stoma Site Marking

The stoma location must be carefully planned to minimize complications and to prevent leakage.

The patient may wear the stoma appliance faceplate prior to the operation. The optimal location of the stoma should be assessed with the patient standing, sitting, and bending. Where does the patient wear the waist of the pants? Range of motion and physical limitations must be evaluated to determine if the patient can visualize the stoma and can manipulate the appliance (e.g., the site may be placed higher on the abdomen for a wheelchair-bound patient). Care must be taken to avoid stoma placement beneath an abdominal pannus to ensure that the stoma remains visible and easy to access for the patient or caretaker.

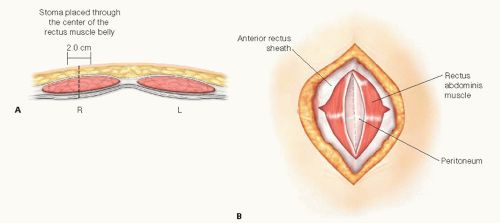

In general, the ileostomy should be placed through the rectus muscle (to minimize parastomal herniation), at the summit of the right paramedian infraumbilical fat pad. The umbilicus, bone, scars, skin folds, and abdominal panni should be avoided (FIG 1). The skin site can be identified with a permanent marker and a scratch can be made with a small needle.

Intraoperative Positioning

Supine or lithotomy position may be used based on the need for an adjunctive procedure for assessment of the colon, rectum, or perineum prior to ileostomy creation (e.g., colonoscopy).

Antibiotic Prophylaxis

Intravenous antibiotics must be given prior to the incision.

FIG 1 • Preoperative marking of the ileostomy site. The ileostomy is placed in the right lower quadrant of the abdomen in a right paramedian, infraumbilical position. |

TECHNIQUES

CREATION OF AN END ILEOSTOMY

Meticulous construction of an end ileostomy is paramount because the ileal contents are liquid, bilious, and voluminous. An everted, spout-shaped end ileostomy (Brooke ileostomy) is best suited to address these challenges.

Abdominal Wall Skin Incision for Exploratory Laparotomy and/or Bowel Resection

If an abdominal incision for bowel resection is necessary, a left paramedian skin incision can be made and angled toward the midline. The abdomen can then be entered through the linea alba. This approach maximizes the distance and amount of skin between the ileostomy and the skin incision.

Ileal Mobilization

The ileum is prepared by releasing the lateral attachments along the pelvic brim and by fully mobilizing the embryonic root of the terminal ileal mesentery to the level of the duodenum.

Stoma Site Skin Incision

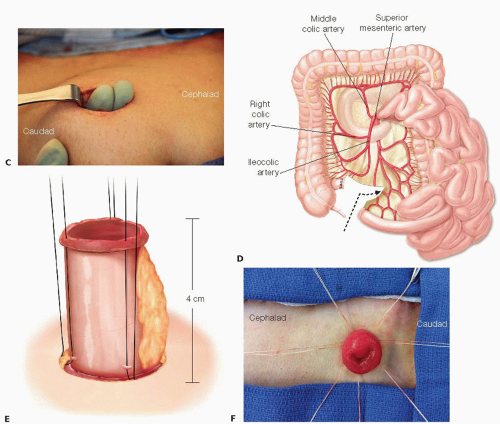

Following the intestinal resection, the skin opening is created in the right lower quadrant at the premarked site. The skin is grasped with a Kocher clamp and a circular skin incision of 2 cm in diameter (FIG 2A) is made tangentially beneath the Kocher clamp with a no. 10 blade. The excised skin disc is removed.

Abdominal Wall Aperture Creation for the Stoma

Bovie electrocautery is used to perpendicularly divide the subcutaneous fat in the right paramedian plane at the ileostomy site. Handheld retractors can be gently used. The subcutaneous fat should be preserved as much as possible.

The anterior rectus sheath is identified and incised in a cruciate fashion for approximately 1 cm in both directions. (The horizontal limb should not be placed too close to the midline.)

Mayo clamps are used to split the rectus muscle bluntly in order to expose the posterior rectus sheath and peritoneum. The rectus muscle fibers are not divided (FIG 2B).

The surgeon places one hand into the abdominal cavity behind the marked stoma site to protect the abdominal contents.

The abdominal cavity is entered through the stoma incision with a thin-point clamp (e.g., Schnidt or tonsil clamp).

The defect in the posterior rectus sheath and peritoneum is widened to allow for passage of the ileum without compromising its mesenteric blood supply. The appropriate defect size is obtained by digitally dilating the stoma site with the tips of two digits to create an approximately 2-cm aperture (FIG 2C).

Ileal Limb Preparation and Placement

At least 6 cm of viable distal or terminal ileum with the adjacent marginal artery should be preserved to maintain an optimal blood supply. The mesentery should not be stripped (FIG 2D). The ileal limb preparation should be performed as early as possible during the course of the operation to allow for sufficient time to observe and assess the ileum’s vascularity. The mesentery must be handled gently to avoid hematomas and mesenteric vascular injury.

The ileum is gently advanced (pushed rather than pulled) through the split muscle and the abdominal wall to about 4 cm beyond the skin level (using a Babcock clamp to grasp the ileum only if necessary). If the ileum and adjacent tissues are too bulky to pass easily through the aperture, the epiploic fat can be excised.

To facilitate a future ileostomy reversal procedure, an adhesion barrier (e.g., Seprafilm®) can be used at the time of ileostomy creation. The adhesion barrier is wrapped around the ileal limb used for the ileostomy, extending along the intraabdominal ileal segment for approximately 5 cm.

The ileal mesentery may be secured to the peritoneum over a length of 3 to 4 cm if a permanent stoma is planned. (This step may prevent torsion, retraction, and prolapse of the ileum.)

Both edges of the rectal stump (or other potentially remaining distal bowel segment) are tagged with polypropylene suture to facilitate identification of the distal intestinal segment for potential ileostomy reversal.

To prevent wound contamination, the surgical abdominal incision is closed next and then covered with a protective wound dressing prior to maturing the stoma.

Stoma Maturation

The staple line is removed from the ileum.

3-0 absorbable (e.g., Vicryl®) interrupted stitches are placed (but not immediately tied), with the stitches running through the following three points (FIG 2E):

end of the ileum (full-thickness)

skin-level base of the stoma (4 cm from the end of the ileum) (seromuscular layer)

Dermis (large bites of the subcuticular layer should be avoided to prevent “buttonholing” and mucosal islands).

One stitch is placed in each quadrant followed by one stitch between each quadrant stitch for a total of seven to eight stitches. Ensure that one stitch is on each side of, and adjacent to, the mesentery (but not through the mesentery).

To allow for more precise placement, each stitch should be individually tagged and tied only when all stitches have been placed. The subcutaneous and mesenteric fat can be tucked in as each suture is tied. The goal is to create a stoma with a spout that protrudes about 2 cm beyond the skin level when completed (FIG 2F).

The ileostomy appliance is placed over the stoma. Waterproof, nonallergenic tape can be used to further secure the edge of the appliance to the skin.

CREATION OF A LOOP ILEOSTOMY

Stoma Site Skin Incision and Abdominal Wall Aperture Creation

The skin incision for a loop ileostomy is similar to the incision for an end ileostomy, except that it can be made slightly longer and slightly oblong. In obese patients, some of the subcutaneous tissues may have to be excised down to the fascia in the shape of a cone (apex at skin level) so as to not constrict the afferent and efferent limbs of the loop ileostomy.

Ileal Limb Preparation and Placement

An ileal segment 20 to 30 cm proximal to the ileocecal valve is identified. The segment is selected so as to maximize mesenteric pedicle length and to avoid compromising the ileocecal valve. The segment’s mesentery and vasculature are preserved (FIG 3A).

Two different orienting sutures are placed on the antimesenteric side of the ileum to mark the afferent and efferent side of the ileal segment (e.g., by using sutures of different colors, or sutures with one knot for the afferent segment and two knots for the efferent segment) (FIG 3B).

An umbilical tape is passed behind the ileum at the ilealmesenteric interface. The ileal loop is advanced through the abdominal wall using the umbilical tape as a guide, taking care to maintain proper orientation and to avoid torsion.

The afferent (productive) limb of the loop ileostomy is placed inferiorly so that its spout will be located on the caudal aspect of the stoma. This requires a partial (about 90 degrees) twist for correct orientation. Alternatively, the afferent limb can be placed on the medial or superior side of the stoma site, depending on surgeon preference and amount of tension on the ileostomy.

Optionally, sutures may be placed between the ileal mesentery and peritoneum to maintain the appropriate rotation specially in obese patients.

The umbilical tape is removed and may optionally be replaced with a supporting rod or a 6-cm segment of red rubber catheter (which may be looped and sutured to itself above the loop ileostomy or secured to the skin).

To prevent contamination of the laparotomy incision, the surgical abdominal incision (midline or left paramedian) is closed next and a protective wound dressing is placed prior to stoma maturation.